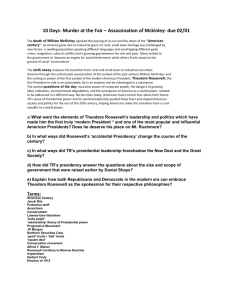

MM - LaFeber continually refers to Teddy Roosevelt as a "policy

advertisement

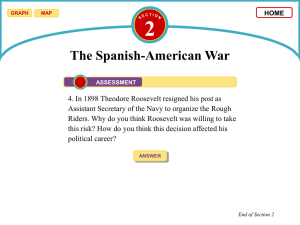

MM - LaFeber continually refers to Teddy Roosevelt as a "policy maker" in his book. He certainly was NOT in the McKinley administration. Second LaFeber wrongly refers to "The Review of Reviews" as the paper of his friend Albert Shaw - without noting that it was NOT Shaw - but Shaw acting on behalf of William T. Stead (whom Rosenberg credits). Finally (and this is just page 91-92 which is the only pages I have looked at) He refers to TR's review of Mahan's book without noting that Mahan sent him a note expressing concern that TR had "completely misread" his book. JD - "Roosevelt also communicated such thoughts, no doubt with characteristic vigor, to President McKinley when the two men enjoyed long rides through Washington parks on warm autumn afternoons. The President and the Assistant Secretary became close friends in late 1897. In a conversation in 1898 McKinley, as hoary legend relates, could not estimate within a couple thousand miles where those "darn" islands were. He nevertheless could, after his long conversations with Roosevelt, judge their location closely enough to agree to Navy Department orders of December, 1897, which instructed Commodore Dewey to strike the Philippines should war occur between the United States and Spain.51 Papers in the McKinley manuscripts indicate that the White House followed the course of the Philippine insurrection in early 1898. Thus when Roosevelt, taking advantage of Long's absence on the afternoon of February 25, ordered Dewey to prepare for war, it is not strange that McKinley and Long did not bother to countermand the orders. Historians have too long overlooked this crucial aspect of Roosevelt's order-sending spree. Although the President and the Secretary of the Navy rescinded more than half of Roosevelt's other plans, they allowed Dewey to prepare to strike Manila. The Assistant Secretary's actions, moreover, did not result from a sudden inspiration; Roosevelt acted after months of conversations with Mahan, Adams, Lodge, and, be it not forgotten, McKinley.52" Page 361. I'll let you haggle over the sources as you're more familiar with their credibility than I. But given this "evidence", the intelligence and political moxie of McKinley, and the likelihood that if Mahan is influencing Lodge, Roosevelt, and whoever else in government, there is a solid "concordance of evidence" that suggests there's some merit to his claim. And let it be further suggested that the similar strategies formed by others prior to Mahan (Harrison and Tracy on pg. 126), the rise of the American battleship navy between 1890 and 1896 (pg. 229) and the annexation of Hawaii for military and commercial reasons all point to a general ideological consensus something along the lines of Mahan's argument. MM - The order to go to war was a standing order prepared by the President and the Secretary of the Navy 3 months prior and could have been issued by the janitor had he been there. If you go to the archives and look up the order it is not signed by Roosevelt - only the cover letter has Roosevelt's signature. LaFeber, was unfamiliar with the nature of the Navy Department command structure and took Teddy's bragging as fact. This whole section of LaFeber is based ultimately upon Teddy Roosevelt's account of the action. Teddy Roosevelt, as he did with the Rough riders charge up San Juan Hill, did what he did with an eye on his personal prestige. Again, LaFeber is projecting Roosevelt (the source of much of this research) back upon McKinley. The reason for that is that McKinley left very little documentation, nor did the actual policy makers in the McKinley administration. Roosevelt, on the other hand left lots. Roosevelt went out of his way both then and later as president when he could manage the government documents, to make himself look more involved than he could possibly have been. JD - Lafeber saw what the Harrison administration (with Tracy) did to build up the navy, the build up of the battleship navy, etc... read the Teddy stuff, doubled back and tripped over Mahan. From there he found his intellectual narrative. He made a couple attempts to qualify his evidence, but in the end, I think you're right that he bought into Teddy and let Mahan drive his narrative. Convenient! MM - Here are some other histories - all of whom take TR's story for the fact: "It was in this context that Theodore Roosevelt, in virtual control of the Navy, began to unfold his plot to engage slumbering America in a war with Spain. With the support of Senator Cabot Lodge, he supervised the naval buildup. He assigned his friend Admiral Dewey to head the Navy in the Western Pacific and gave him specific orders to strike the Spanish in Manila Harbor in the event of war. He wrote, “”Whenever I was left as Acting Secretary (of the Navy), I did everything in my power to put us in readiness. I knew that in the event of war Dewey could be slipped like a wolf-hound from a leash, I was sure that if he were given half a chance he would strike instantly and with telling effect.” Teddy Roosevelt, Dewey, Lodge, Mahan were friends and talked a lot about this. The people in charge, Long, McKinley etc did not and were actually opposed to this more imperialist push of the younger crew. But McKinley left very few papers and little or nothing of his ideas. So, historians who need evidence start digging and find LOTS of evidence for TR who was there and claims to know. So, TR wins. LaFeber is a VERY smart guy. He is a terrific historian. He was also a grad student when he did this research originally. It made sense, it had evidence, it fit his narrative he wrote it and it stuck. The problem is that TR never had the kind of authority in the Navy department that he claimed. He was never in "virtual control of the Navy" except in his own head. The flurry of orders were standing orders in case of a war. TR rushed them out while Long was away. So, LaFeber has a case, the evidence is there. Roosevelt, who does believe everything LaFeber says he does, does issue the orders, does issue them for the reasons LaFeber says - BUT does not have the actual power or authority other than just bureaucratic to do so. Then after the war, McKinley seems to concede what has happened and talks of the imperialism of righteousness and seems to confirm it all. The question, why does the US GO to war with Spain is still one that has to deal with McKinley and Long - not TR, Lodge and Mahan. McKinley was, in the end, pushed till he felt he had no other alternative. Also, Spainish officials needed an honorable way to get out of their expensive rebellious colonies and losing to the US seemed to allow them that out.