Context - TerpConnect

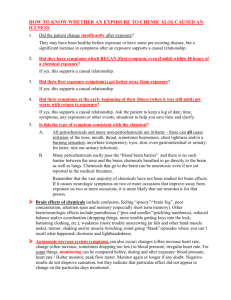

advertisement

Chapter 14: Causes, Contrasts, and the Nontransitivity

of Causation1

Cei Maslen

1. Introduction

Whether one event causes another depends on the

contrast situation with which the alleged cause is

compared. Occasionally this is made explicit. For

example, a toothpaste company claims that regular

brushing with their product will cause teeth to become

up to two shades whiter than with “another leading

brand”. Here, the comparison not only helps to specify

a range of shades of white, but also to specify a

contrast situation. Regular brushing with their product

is not compared to, say, irregular brushing with their

product or not brushing at all, but to regular brushing

with another leading brand.

More often the contrast situation is not made

explicit, but is clear from the context. Hence, in

general, the truth and meaning of causal statements

depend on the context in which they occur. In section

2, I give a more complete formulation of this claim,

Ch 14

2

illustrate it with an example and compare it to similar

and superficially similar views. The theory is

incomplete without a description of how contrast events

are fixed by the context, which I supply in section 3.

In section 4, I discuss the context dependence of

counterfactuals. Of course, a major motivation for the

theory is the extent to which it can avoid obstacles

that have defeated other theories of causation,

problems such as the nontransitivity of causation,

preemption, causation by absences, and causation under

indeterminism. In section 5, I explain how a

contrastive counterfactual account solves the first of

these problems: analyzing the nontransitivity of

causation.2

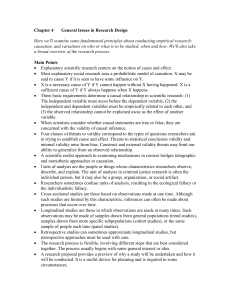

2. A Contrastive Counterfactual Account

Causal statements are systematically dependent on

context.3 The meaning and truth-conditions of causal

statements are dependent on contrast events that are

seldom explicitly stated, but are fixed by

conversational context and charity of interpretation.

Occasionally confusion about contrast events leads to

misunderstandings and indeterminacy of meaning and

Ch 14

truth-value. This may be expected when causal

statements are taken out of context, for example, in

some philosophical discussions.

This isn’t to make causation a subjective matter.

The causal structure of the world is an objective,

mind-independent three-place relation in the world

between causes, contrasts, and effects. (Compare this

to discovering that motion is relative to frame of

reference. This is not to discover that motion a

subjective matter.)

It would perhaps be ideal to study the properties

of causal statements (e.g. nontransitivity and context

dependence) without appealing to a specific formal

analysis of our concept of causation. All formal

analyses of causation are controversial, and

complicated. The claims that causation is contextdependent, and that causation is non-transitive are

partly independent of any specific analysis. However,

in practice it is impossible to have detailed

discussions of these aspects without settling on one

analysis. The few philosophers who discuss the context

dependence view can be classified into all the major

schools of thought on causation. Hitchcock4

3

Ch 14

4

incorporates it into a probability-raising account.

Field5 discusses probabilistic and non-probabilistic

versions of a regularity or law-based view. Holland6

presents a counterfactual account. I support a

counterfactual account also, and concentrate on

singular causal claims.

2.1 Account1

For distinct events c, c* and e, c is a cause of e

relative to contrast event c* iff c and e actually

happened and if c had not happened, but contrast

event c* had happened instead, then e would not

have happened.

This account takes events as the fundamental causal

relata. Either Kim’s or Lewis’s definitions of events

would serve this purpose.7 My hope is that causal

sentences with other kinds of relata (physical objects,

processes, facts, properties, or event aspects) can be

reexpressed in terms of event causation, but I will not

argue for this claim here.8 I discuss counterfactuals

briefly in section 4 below. I think that our intuitive

Ch 14

5

understanding of this grammatical form is strong, so I

do not commit myself to an analysis here.9

The only restrictions I place on the contrast

event is that it be compossible with the absence of the

cause and distinct from the absence of the cause.10 I

also require that the cause, effect and contrast event

be distinct events.11 This may seem hopelessly liberal.

What is to stop someone from claiming that brushing my

teeth this morning, in contrast to being hit by a

meteorite, was a cause of my good humor, or that the

price of eggs being low, in contrast to the open fire

having a safety guard, was a cause of the child’s burn?

The inanity of these examples arises from inappropriate

contrast events. Describing appropriateness of contrast

is a difficult task, and I have little more to say

about it at this stage than that events are usually

contrasted with events that occur at a similar time,

and that might have replaced them.12

Let’s assume that any complex of events (the event

which occurs just in case the constituent events occur)

is itself an event. It will be useful to define a

contrast situation as the complex of a contrast event

Ch 14

6

and the event in which the absence of the cause

consisted.13 With this terminology, account1 is:

Event c is a cause of event e relative to a

contrast situation iff had the contrast situation

happened, then e would not have happened.

There may also be explicit and implicit

alternatives to the effect. For example, a friend’s

opinions were a cause of my renting the video “Annie

Hall” rather than the video “Mighty Aphrodite”.

Account1 can be generalized in the following way to

allow for contrasts to the effect and for a range of

implicit contrasts. (However, I will mostly continue to

work with the simpler account1).

2.2 Account2

Event c, relative to contrast situations {c*}, is

a cause of event e, relative to contrast

situations {e*}, iff had any events from {c*}

occurred, then an event from {e*} would have

occurred.14

Ch 14

7

2.3 Illustrations

Here are two examples to illustrate the context

dependence of causation. First, suppose I have three

cookie recipes: hazelnut cookies, walnut cookies and

pecan cookies. I decide to make hazelnut cookies, then

offer one to Stuart. Unfortunately Stuart has a nut

allergy; he is allergic to all nuts. He eats the cookie

and becomes ill. Was making the hazelnut cookies one of

the causes of his illness?

Well, if I hadn’t made the hazelnut cookies I

would have made the pecan cookies, because I have only

three cookie recipes and I have no walnuts in the

house. So in one sense, making the hazelnut cookies was

not a cause of his illness. Relative to making pecan

cookies, making hazelnut cookies was not a cause of his

illness. However, relative to the alternative of making

no cookies at all, making the hazelnut cookies was a

cause of his illness. Taken out of context, there is no

correct answer to the question whether making hazelnut

cookies was a cause of Stuart’s illness. Out of

context, the only valid claims we can make are relative

claims. However, the conversational context and

unspoken assumptions can make some alternatives more

Ch 14

8

salient than others. Our awareness that I only have nut

cookie recipes made the alternatives of baking pecan

cookies and walnut cookies salient alternatives for us,

and in the context of this paper the causal claim

“making hazelnut cookies was a cause of his illness” is

naturally interpreted as meaning “making hazelnut

cookies, relative to making pecan cookies or walnut

cookies, was a cause of his illness.”

The second example, of an electric circuit, comes

from Daniel Hausman, though he uses it for a different

purpose. “The ‘weak circuit’ and the ‘strong circuit’

power a solenoid switch, which closes the ‘bulb

circuit’. If only the weak circuit is closed, the

current through the solenoid is 4 amperes. If only the

strong circuit is closed, the current through the

solenoid is 12 amperes. If both are closed, about 16

amperes flow through the solenoid. It takes 6 amperes

to activate the solenoid switch, close the bulb

circuit, and turn on the light bulb. Whether the weak

circuit is closed or not affects how much current is

flowing through the solenoid, but it has no influence

on whether the light goes on.”15

Ch 14

9

[Figure 1]

Suppose that on this occasion, I close both the

strong and the weak circuit, a current of 16 amperes

flows through the coil, the solenoid switch closes, and

the bulb lights. Was the presence of a current of 16

amperes through the coil a cause of the bulb lighting?

The answer to this question is relative to the contrast

event.

16 amperes flowing through the coil, rather than 12

amperes flowing through the coil, was not a cause of

the bulb’s lighting.

16 amperes flowing through the coil, rather than 4

amperes flowing through the coil, was a cause of the

bulb’s lighting.

16 amperes flowing through the coil, rather than 0

amperes flowing through the coil, was a cause of the

bulb’s lighting.

Ch 14

10

The fact that there are cases like these where the

context dependence is clear, gives excellent support to

the context dependence view.

2.4 Other views

At this point, it will be helpful to compare account2

to similar and superficially similar views.

I am not proposing a revisionary account of

causation. The realization that causation is contextdependent and that this can lead to misunderstandings

might prompt us to propose a revisionary account of

causation. We could suggest that in the future, in

order to avoid misunderstandings in precise or

important uses of causal claims, we should always state

alternative events together with our causal claims. We

could even follow Bertrand Russell in suggesting that

we abandon the concept of causation altogether.16

Instead we would only use precise counterfactuals with

our assumptions spelt out. But the state of our causal

concept does not warrant such an extreme reaction.

The context dependence that I have described in

the concept of “a cause” is additional to the generally

accepted context dependence of “the cause” or “the

Ch 14

11

decisive cause”. I am only concerned here with what it

takes to be “a cause” or “one of the causes” of a given

effect. The context dependence of the concept of “the

cause” is more obvious. It might be suspected that

there is only one source of context dependence here and

that is from the concept of “the cause”. It could be

argued that we confuse “a cause” for “the cause” when

we read the examples, and this is why we find them

convincing. However, this simply isn’t borne out by our

intuitions. We do have an additional contextual element

here.

The context dependence of causation is distinct

from the widely accepted view that explanation is

context-dependent. Van Fraassen is the major defender

of the latter view: “If, as I’m inclined to agree,

counterfactual language is proper to explanation, we

should conclude that explanation harbors a significant

degree of context-dependence.”17 He argues that the

context dependence of explanation takes the form of

determining both the salience of explanatory factors

and also the contrast class. However, those who claim

that explanation is dependent on context assume that

causation is independent of context. For example, it

Ch 14

12

seems to be implied by van Fraassen’s claims that the

propositions of the causal net are scientific

propositions, and “scientific propositions are not

context-dependent in any essential way”18 that causal

statements are (essentially) independent of context. I

disagree; both explanation and causation are contextdependent.

Account2 is similar in many ways to Lewis’s recent

“Causation as influence” view and to event-feature

views of causation, for example, Paul’s “Aspect

Causation” view. I do not have space to discuss all the

similarities and differences here. However, note that

all three views imply that causal statements are

strongly context dependent. Lewis talks of “a

substantial range of not-too-distant alterations” of

the cause; what constitutes a substantial range, and

what constitute not-too-distant alterations of the

cause presumably differs with context. Event-feature

views require the context to determine event features

from event nominalizations.

Ch 14

13

3. Contrast Events and Context

The context of a statement is the circumstances in

which it occurs. The truth of a statement may depend on

features of the context as well as on matters of fact.

Dependence on matters of fact is contingency;

dependence on features of context is context

dependence. Following the two-stage scheme of

Stalnaker, an interpreted sentence together with a

context determines a proposition, and a proposition

together with a possible world determines a truth

value.19 Hence, which proposition is expressed by an

interpreted sentence may depend on the context in which

it occurs. A classic example of a context-dependent

sentence is “I went to the store”; its interpretation

depends on the identity of the speaker, due to the

indexical “I”.20

In general, a large variety of contextual features

may be required to interpret a sentence on a particular

occasion. For example “the intentions of the speaker,

the knowledge, beliefs, expectations, or interests of

the speaker and his audience, other speech acts that

have been performed in the same context, the time of

utterance, the effects of the utterance, the truth-

Ch 14

14

value of the proposition expressed, the semantic

relations between the proposition expressed and some

others involved in some way”.21 Features of context

such as speaker and time of utterance are almost always

obvious and readily observable. The set of contrast

events is a theoretical feature of context; hence, we

owe a description of how contrast events connect with

more obvious features of context. Otherwise, when

disputes arise it might seem as though the

metaphysician is magically summoning the set of

contrast events or choosing the set to fit her case.

Suppose that the contrast event is what the

speaker has in mind for replacing the cause. That is,

it is what the speaker has in mind to be different in

an imagined counterfactual situation where the cause is

removed. Two objections to this immediately arise.

Firstly, unphilosophical speakers may not have anything

of the right sort in mind when uttering causal

statements. When asked what they had in mind, many

speakers may admit that they hadn’t thought about it.

However, usually these speakers then have no problem

responding with a contrast event when prompted. These

responses give the intended interpretation of the

Ch 14

15

original causal statement, in some sense of “intended”.

Secondly, as we are not mind readers, if the “have in

mind” picture were the whole story then communication

would be very haphazard.

The rest of the story is that which contrast set

the speaker has in mind, if not communicated directly,

may be clear to the audience by the previous course of

the conversation, acknowledged assumptions,

limitations, plans, and presuppositions. General

pragmatic principles play a large part in this. The set

of contrast events is what Lewis calls a “component of

conversational score”.22 We have a tendency to

interpret utterances generously or charitably, as true

or probable, relevant, useful and informative. The set

of contrast events is fixed and developed through the

course of the conversation. Sometimes the set is left

unsettled or vague until a dispute arises. In a few

cases this vagueness even leads to ambiguity in the

causal statement.

Often there are physical limitations on the ways

in which the cause could have been omitted. This gives

us a “default” set of contrast events. Consider the

following example. My opponent and I are both very

Ch 14

16

competitive. We each would have been happy to win, but

we are both unhappy when we reach a draw at chess.

“Reaching a draw at chess was a cause of us both being

unhappy.”

Presuming that we finish the chess game, there are only

two ways in which the event of reaching a draw could

have been omitted: by my winning the game, or by my

opponent winning the game. Hence, there are two natural

interpretations of the causal statement:

“Reaching a draw at chess, in contrast to my winning

the game, was a cause of us both being unhappy”;

“Reaching a draw at chess, in contrast to your winning

the game, was a cause of us both being unhappy.”

Either of these alternative outcomes would have

left one of us happy. Hence reaching a draw can truly

be called a cause of us both being unhappy. The natural

set of contrasts here are the events which the absence

of the cause would have consisted in. Given our

assumption that we did actually finish the chess game,

the absence could only have consisted in my winning the

game, or my opponent winning the game.

Ch 14

17

In some cases, there is only one probable way in

which the cause would have been omitted and this is the

natural or default contrast. Suppose that my opponent

is a much better chess player than I. If we hadn’t

reached a draw, he would almost certainly have won.

Given our assumptions, the contrast situation here is

naturally limited to one alternative. The following

causal claim is probably true in that context.

“Reaching a draw on the chess game was a cause of my

opponent being unhappy.”

The default contrast is always overruled by what

the speaker has in mind or intends as the contrast. For

instance, suppose I mistakenly believe that I am the

better player. I could have in mind a contrast with the

case in which I had won the game and deny the above

causal claim. (If my opponent does not realize I have

this mistaken belief, then this will probably lead to

misunderstanding). Even if I recognize that my opponent

would have won the game if we hadn’t drawn, I could

make it clear that I’m contrasting with a wider set,

and then deny the causal statement above. I could

Ch 14

18

contrast with the set {playing the chess game and my

winning, playing the chess game and his winning, not

playing the chess game at all}.23

4. The Context Dependence of Counterfactuals

The counterfactual analysis of causation is one of the

most popular approaches to analyzing causation. Hence,

it is strange that counterfactuals are widely

acknowledged to be context-dependent, while causation

is not widely acknowledged to be so.

The context dependence of counterfactuals has been

observed and discussed in most major works on

counterfactuals.24 Here are some classic examples

exhibiting context dependence.

If Caesar had been in command in Korea he would

have used the atom bomb.

If Caesar had been in command in Korea he would

have used catapults. [Example due to Quine]

If this were gold it would be malleable.

If this were gold then some gold things would

not be malleable. [Example due to Chisholm]

Ch 14

19

If New York City were in Georgia then New York

City would be in the South.

If New York City were in Georgia then Georgia

would not be entirely in the South. [Example due

to Goodman]

All of these counterfactuals are context-dependent.

Consider just the first pair. Each statement can be

reasonably asserted in the same situation. (We

presuppose that Caesar was ruthless, ambitious and

indifferent to higher authority.) Yet the first

statement implies that the second statement is false.

(We presuppose that it is possible that Caesar was in

command in Korea and it is not possible that he uses

both catapults and atom bombs.) The second statement

cannot be both true and false, so it must express at

least two different propositions depending on factors

other than the background facts. It is contextdependent.

Acknowledging the context dependence of

counterfactuals can help us to understand the context

dependence of causation. I do not wish to commit myself

Ch 14

20

to one analysis of counterfactuals here. However, let

me mention how two successful and sophisticated

analyses of counterfactuals account for their context

dependence. One formulation of Lewis’s analysis of

counterfactuals is as follows:

“A counterfactual ‘If it were that A, then it would be

that C’ is (non-vacuously) true if and only if some

(accessible) world where both A and C are true is more

similar to our actual world, overall, than is any world

where A is true but C is false”25

On his account, the context dependence of

counterfactuals arises because our judgments of overall

similarity of possible worlds depend on context. “The

delineating parameter for the vagueness of

counterfactuals is the comparative similarity relation

itself: the system of spheres, comparative similarity

system, selection function, or whatever other entity we

use to carry information about the comparative

similarity of worlds”.26

The tacit premise view of counterfactuals is

presented by Chisholm and by Tichy.27 On this view, a

Ch 14

21

counterfactual is true iff its antecedent together with

its tacit premises logically entail its consequent, and

the tacit premises are true. The tacit premises are

simply those assumptions which have been presupposed in

the conversation or which the speaker has in mind on

the occasion of utterance. The context dependence is

obvious on this view.

It is interesting that Lewis observes in his

original paper on causation “The vagueness of

similarity does infect causation, and no correct

analysis can deny it”.28 His original theory already

accounts for some context dependence, admittedly in a

subtle way.

5. The Nontransitivity of Causation

Is causation transitive? That is, is it true for all

events a, b and c that if a is a cause of b and b is a

cause of c then a is a cause of c? Some causal chains

are clearly transitive. Suppose that the lightning is a

cause of the burning of the house, and the burning of

the house is a cause of the roasting of the pig.

(Suppose that the pig was trapped in the house). Then

Ch 14

22

surely the lightning is also a cause of the roasting of

the pig. But is this true for all events a, b, and c?

In the past, the transitivity of causation was

commonly assumed in the literature without argument.29

But more recently a host of ingenious examples have

been presented as counterexamples to the transitivity

of causation.30 Before discussing these examples, let’s

briefly consider one argument for the transitivity of

causation.

The only argument that I have found in the

literature for the claim that causation is transitive

comes from Hall. Hall argues “rejecting transitivity

seems intuitively wrong: it certainly goes against one

of the ways in which we commonly justify causal claims.

That is, we often claim that one event is a cause of

another precisely because it causes an intermediate,

which then causes another intermediate, ... which then

causes the effect in question. Are we to believe that

any such justification is fundamentally misguided?”31

This is an important consideration. I agree with

Hall that it is common practice to refer to

intermediates in a causal chain in justifying causal

claims. This seems to apply across many different

Ch 14

23

fields of application of the singular causal concept:

history, science, law, and ethics. I don’t think that

this practice is fundamentally misguided, but it may be

a rule of thumb, which should be supplemented with

restrictive guidelines. If we are to reject

transitivity, we have a pressing need for a general

rule for distinguishing the cases in which transitivity

holds from the cases in which it fails, and an

explanation of why transitivity sometimes fails. Hall

agrees with me here. He issues a challenge: “Causation

not transitive? Then explain under what circumstances

we are right to follow our common practice of

justifying the claim that c causes e by pointing to

causal intermediates.”32 I take up this challenge in

the next section after presenting the counterexamples.

The alleged counterexamples to transitivity are

diverse; I will describe three difficult and

representative cases - ‘bomb’, ‘birthday’, and ‘purple

fire’. The first comes from Field.33 Suppose that I

place a bomb outside your door and light the fuse.

Fortunately your friend finds it and defuses it before

it explodes. The following three statements seem to be

true, thus showing that causation is nontransitive.

Ch 14

24

(1a) My placing the bomb outside the door is a cause of

your friend’s finding it.

(1b) Your friend’s finding the bomb is a cause of your

survival.

(1c) My placing the bomb outside the door is not a

cause of your survival.

On a more cheerful note, suppose that I intend to

buy you a birthday present, but when the time comes I

forget. Fortunately, you remind me and I buy you a

birthday present after all. The following three

statements seem to be true, thus showing that causation

is nontransitive.

(2a) My forgetting your birthday is a cause of your

reminding me.

(2b) Your reminding me is a cause of my buying you a

birthday present.

(2c) My forgetting your birthday is not a cause of my

buying you a birthday present.

Ch 14

25

Finally, consider Ehring’s purple fire example.34

I elaborate. Davidson puts some potassium salts into a

hot fire. The flame changes to a purple color but

otherwise stays the same, because potassium compounds

give a purple flame when heated. Next, the heat of the

fire causes some flammable material to ignite. Very

soon the whole place is ablaze, and Elvis sleeping

upstairs, dies of smoke inhalation. The following three

statements seem to be true and again show that

causation is nontransitive.

(3a) Davidson’s putting potassium salts in the

fireplace is a cause of the purple fire.

(3b) The purple fire is a cause of Elvis’ death.

(3c) Davidson’s putting potassium salts in the

fireplace is not a cause of Elvis’ death.

6. A Contrast Analysis of the Counterexamples

Transitivity is only defined for binary relations, but,

on the context dependence view, causation is not a

binary relation. (It is either a three place relation

between a cause, a context, and an effect, or a fourplace relation between a cause, two sets of contrast

Ch 14

26

events, and an effect, depending on how you count it.)

We will discuss a related property, the “variablecontext transitivity” of the three-place causal

relation. The three-place causal relation has

“variable-context transitivity” just in case for all

events e1, e2, e3, and for all contexts c1, c2, c3, if e1

causes e2 in context c1, and e2 causes e3 in context c2,

then e1 causes e3 in context c3. That is, the causal

relation has variable-context transitivity just in case

it appears transitive no matter how you change the

context.

Let’s analyze the bomb example. The example can be

interpreted in many different ways depending on the

contrast events assumed in statements (1a), (1b), and

(1c). Two natural contrasts with the cause in (1a) are

the contrast with my placing nothing outside the door

and the contrast with my carefully concealing the bomb

outside the door. My placing the bomb outside the door,

in contrast to my placing nothing outside the door, is

a cause of your friend’s finding the bomb, because if I

had placed nothing outside the door your friend

wouldn’t have found the bomb. My placing the bomb

outside the door, in contrast to my carefully

Ch 14

27

concealing the bomb outside the door, is a cause of

your friend’s finding the bomb, because if I had

carefully concealed the bomb outside the door your

friend would not have found it (let us say).

Some interpretations of the example do not yield

counterexamples to transitivity. Statement (4c) of the

following is false: it seems plausible that my placing

the bomb outside the door, in contrast to my carefully

concealing the bomb outside the door, is a cause of

your survival. So the following causal chain is

transitive.

(4a) My placing the bomb outside the door (vs.

carefully concealing it) is a cause of your friend’s

finding it (vs. overlooking it).

(4b) Your friend’s finding the bomb (vs. overlooking

it) is a cause of your survival (vs. death).

(4c) My placing the bomb outside the door (vs.

carefully concealing it) is not a cause of your

survival (vs. death).

However, with other natural contrasts, we do have

a nontransitive causal chain. For example, all three of

the following statements seem true.

Ch 14

28

(5a) My placing the bomb outside the door (vs. placing

nothing outside the door) is a cause of your friend’s

finding the bomb (vs. finding nothing).

(5b) Your friend’s finding the bomb (vs. finding

nothing) is a cause of your survival (vs. death).

(5c) My placing the bomb outside the door (vs. placing

nothing outside the door) is not a cause of your

survival (vs. death).

We can develop a sufficient condition for a causal

chain to be transitive from a special case of inference

by transitivity of counterfactuals:

(T) φ □→ χ , χ□→φ, φ□→ψ χ□→ψ35

Consider a general causal chain:

(6a) a, with contrast situation c1 is a cause of b,

with contrast situation d1.

(6b) b, with contrast situation c2, is a cause of e,

with contrast situation d2.

(6c) a, with contrast situation c3, is a cause of e,

with contrast situation d3.

Ch 14

29

Suppose (C1) c1=c3, d1= c2, d2= d3, (in other words,

events a, b, and e have the same contrasts throughout)

and (C2) if c2 had occurred then c1 would have to have

occurred (a backtracking counterfactual).36 From (T),

and account2, these conditions are sufficient for a

causal chain to be transitive.

This can help us to understand what is going on in

example (5) to yield nontransitivity. Example (5)

passes (C1), but fails (C2). It is not true that had

your friend found nothing outside the door then I would

have to have placed nothing outside the door. Had your

friend found nothing outside the door then it might

have been because I carefully concealed the bomb

outside the door and she overlooked it. There is a

sense in which the contrast situations in the example

are incompatible with each other, and this

incompatibility leads to nontransitivity.

Let’s return briefly to the other counterexamples.

Here is one natural interpretation of the birthday

example:

(7a) My forgetting your birthday (vs. my remembering

your birthday) is a cause of your reminding me (vs.

Ch 14

30

your forgetting to remind me, or our both forgetting

your birthday).

(7b) Your reminding me (vs. your forgetting to remind

me, or our both forgetting your birthday) is a cause of

my buying you a birthday present (vs. buying you

nothing).

(7c) My forgetting your birthday (vs. my remembering

your birthday) is not a cause of my buying you a

birthday present (vs. buying you nothing).

Notice that condition (C2) fails. It is not true that

if you had forgotten to remind me about your birthday

then I would have to have remembered by myself. If you

had forgotten to remind me about your birthday then I

might have forgotten too. Also, it is not true that if

we had both forgotten your birthday then I would have

to have remembered your birthday. On the contrary, if

we had both forgotten your birthday then I would not

have remembered your birthday.

Here is the example with some other contrast

situations. Statement (8b) is false: if I had

remembered your birthday by myself then I would have

bought you something (let us say!) So the example

exhibits transitivity. Furthermore, conditions (C1) and

Ch 14

31

(C2) are satisfied. The same events always have the

same contrasts throughout, and if I had remembered your

birthday by myself then I would have remembered your

birthday.

(8a) My forgetting your birthday (vs. my remembering

your birthday) is a cause of your reminding me (vs. my

remembering your birthday by myself).

(8b) Your reminding me (vs. my remembering your

birthday by myself) is a cause of my buying you a

birthday present (vs. buying nothing).

(8c) My forgetting your birthday (vs. my remembering

your birthday) is not a cause of my buying you a

birthday present (vs. buying nothing).

Finally, here is the purple fire example with some

natural contrasts spelled out:

(9a) Davidson’s putting potassium salts in the

fireplace (vs. Davidson’s putting nothing in the

fireplace) is a cause of the purple fire (vs. a yellow

fire).

(9b) The purple fire (vs. no fire) is a cause of

Elvis’s death (vs. Elvis’s survival).

(9c) Davidson’s putting potassium salts in the

fireplace (vs. Davidson’s putting nothing in the

Ch 14

32

fireplace) is not a cause of Elvis’s death (vs. Elvis’s

survival).

This case is nontransitive because it fails both

conditions (C1) and (C2). The event of the purple fire

is contrasted with a yellow fire in (9a) but contrasted

with no fire in (9b). Furthermore, it is not true that

if there had been no fire then Davidson would have to

have put nothing in the fireplace. If there had been no

fire, he might have decided to put potassium salts in

the fireplace anyway.

7. A Fine-grained Event Analysis of the Counterexamples

Hausman describes how allowing for fine-grained events

enables us to explain examples of this sort without

rejecting the transitivity of causation.37 The example

is not of the right form to be a counterexample to

transitivity, because of the equivocation in which

event is being referred to by the phrase “the purple

fire”. In terms of Kimian events, “the purple fire”

could either designate the triple [the fire, being

purple, time] or the triple [the fire, being a fire,

time]. In terms of Lewisian events, the phrase could

Ch 14

33

either designate a strong event “the purple fire” which

is essentially purple, or designate a weak event “the

fire” which is only accidentally purple. It is the

strong event of the purple fire (or the triple [the hot

purple fire, being purple, time]) which is caused by

Davidson’s action, and it is the weak event of the fire

(or the triple [the purple fire, being a fire, time])

which is a cause of Elvis’s death.

The fine-grained event analysis of the purple fire

example is similar to the analysis in terms of implicit

contrasts that I gave above. While Hausman locates

context dependence in the reference of the phrase “the

purple fire”, I locate the context dependence in the

interpretation of the whole sentence, “Davidson’s

putting potassium salts in the fireplace is a cause of

the purple fire”. However, if the phrase “the purple

fire vs. a yellow fire” designates a strong event of

the purple fire and the phrase “the purple fire vs. no

fire” designates a weak event of a purple fire, which

they plausibly do, then it can be shown that the two

analyses of this example are equivalent.

However, I do not see how the fine-grained event

analysis can explain the nontransitivity of the bomb

Ch 14

34

example in a similar fashion. Perhaps we can locate an

equivocation in the event referred to by the phrase

“your friend’s finding the bomb” by looking at the

contrast analysis of the example. Suppose that there

are two different events referred to by the phrases

“your friend’s finding the bomb, in contrast to your

friend’s overlooking the bomb” and “your friend’s

finding the bomb, in contrast to there being no bomb

and your friend finding nothing”, and that the phrase

“your friend’s finding the bomb could designate either

event. Perhaps we could define event1 as an event that

occurs in worlds in which I place a bomb outside the

door and your friend finds it, and does not occur in

worlds in which I place a bomb outside the door and

your friend overlooks it or in worlds in which I do not

place a bomb outside the door. And we could define

event2 as an event that occurs in worlds in which

either I place a bomb outside your door and your friend

finds it or I place a bomb outside your door and your

friend overlooks it, and does not occur in worlds in

which I do not place a bomb outside the door.

Then,

after some work, we could show that the example

Ch 14

35

involves an equivocation rather than a failure of

transitivity.

But how could the phrase “your friend’s finding

the bomb” designate event2? (Surely overlooking the

bomb is not just another way of finding the bomb!) In

order to analyze the example in this way we have built

conditions external to the event into the event

identity conditions for the event. The contrast

analysis of this example is more plausible.