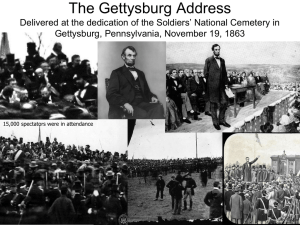

Never Forget What They Did Here - Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse

advertisement