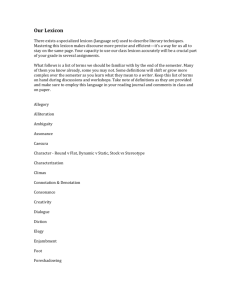

If we were to create a graph of vocabulary growth and lexicon

advertisement

Morphological Analysis Of English Neologisms Dr. Jelena VUJIC, University of Belgrade, Serbia Neologisms have always been of great interest to linguists. They not only reflect the latest trends and developments in the language but they are a language representation of social, cultural and historical changes. From the morphological point of view they are especially interesting as they very often demonstrate how imaginative and unpredictable language can be. If we were to create a graph of vocabulary growth and lexicon expansion in the English language I am sure that two highest peaks marking the most intensive vocabulary growth would be the periods of Renaissance and the 20tjh century, particularly the second half of the last century. This is not surprising bearing in mind the fact that the lexicon is the part of language that most obviously and most rapidly reflects the social changes. As the civilization develops in technical, scientific, cultural and economic way so does the language, especially the lexicon following the trends of social evolution. As Crystal, (1995, 171) remarks:“ The lexicon is the particularly sensitive index of a historical, social and technological change”. Since the 20th century was characterized by the rapid development and progress in all the aspects of human activity and since the Anglo-Saxon culture dominated in the above mentioned, no wonder it is the English language, which, among just few others, has been undergoing a major expansion of its lexicon. New words are being created on a daily basis and thanks to the means of mass communication they spread incredibly fast. New words are formed to name new phenomena and as Leech (1969, 44) points out: “If a new word is coined, it implies the wish to recognize a concept or property which the language so far can only express by phrasal or clausal description”. These newly-formed words are often referred to as neologisms, coinages or portmanteau words. Pei (1966:42) defines the coinage as “ the creation, usually deliberate, occasionally accidental, of a new, artificial word which had no previous membership in the language” while a neologism (1966: 179) “is a newly coined word or expression; a use of an old word in a new sense”. Crystal (1995:455) however, equalizes the terms and says” neologism- The creation of a new word out of existing elements; also called a coinage”. New words may be loans, calques or nonce formations. Majority of neologisms may be broadly classified into the last category which Bauer (1983:45) defines as “ a new complex 120 word coined by a speaker/ writer on the spur of the moment to cover some immediate need.” The category of nonce formations may consist of numerous subclasses such as a) derivatives b) compounds and c) blends. Some authors tend to understand blends as a subtype of compound neologisms. In any case, through every new- word-formation we are exploiting the productivity of the language system and its potentials. However, not all the neologisms “live to tell”, in other words survive in the language and become the part of the lexicon. Many of them serve their purpose in a certain occasion, and 120 then become lost. Nowadays owing to the means of mass communication, we, at least have the written evidence of their existence. Whether a new term is going to be widely accepted or not depends on many conditions, most of which are of social rather than linguistic nature. Even if they do not become widely accepted or institutionalized they cannot be ignored, particularly from the linguistic aspect as they reflect the tendencies of the contemporary language, in this case the English language. As it has previously been mentioned, new words are formed daily, and it is extremely difficult to keep the track of all the neologisms as some of them are restricted to the use in certain registers and contexts. In further text I will try to give a morphological analysis of the ones that I found most interesting, illustrative, eye-catching and, of course, up-to-date. The first group of examples which includes blends seems to be the most numerous. In other words blending as a word-formation process appears to be a quite productive and handy way to coin new words. It is particularly the case when it comes to forming nouns. Examples: a) he+bimbo>himbo – a good-looking but not very smart male “After three Garbage albums, Manson hasn't yet become a tedious pop princess. Undeniably charismatic, she can be distinguished from most of the pop world's thrusting teens and vainglorious himbos by one easy test: she has opinions. —Sacha Molitorisz, "Talking Trash," Sydney Morning Herald, January 25, 2002 b) charity+mugger> chugger – a professional fund raiser who approaches people in the street to ask them for charity “The clampdown applies to "charity muggers", known as "chuggers", who stop people in the street to ask for direct debit pledges. —Ben Leapman, "Tough new curbs on the charity 'muggers'," The Evening Standard (London, England), May 2004 c) husband+lesbian>hasbian- a female person who used to be a lesbian but now is married "Say that you'd only just got used to telling your friends your daughter was a lesbian and do not relish having to inform them that she is now a hasbian." —"Dear Dawn," The Dominion, November 20, 1995” d) was+lesbian>wasbian- a female who used to be a lesbian but is now heterosexual "On the island she will meet up with her pal Mary Sharon (a slightly subdued, slightly aging radical-feminist-lesbian attorney), Teddie (ex-love of Rachel and only slightly less-true-believer), Rachel (who's hosting the reunion on her tiny island), Grace (enigma extraordinaire), and Julie (ex of Tyler's, now a 'wasbian')." —Beren De Motier, "Mystery Forum," The Lesbian Review of Books, October 31, 1999 e) testify+lying>testifying – lying under oath, especially by a police officer to help get a conviction 120 The lawsuit reserves its harshest allegations for Detective William Mahoney — who is already facing disciplinary action for his testimony in the high-profile case — and for the city, which the lawsuit says has tolerated a pattern of "testilying" by police officers. —Francie Latour, "Wrongfully convicted ex-prisoner faults Hub police in suit," The Boston Globe, April 19, 2002 Example c) is particularly interesting as we encounter a spelling change. In the final constituent hasbian there is the letter a in the first syllable which is present in neither of the two immediate constituents. This change, however does not influence the pronounciation of the final constituent. In examples c) , d) and e) we encounter the phonaesthesia or the sound symbolism, as the creator of these novelty words obviously felt there was a meaningful connection between the sounds and the phenomena they name. Not only new nouns are formed by the means of blending but verbs and adjectives as well, although they are much fewer. I have come across just the following two examples. Examples: f) man+landscape>manscape- the artful shaving and trimming of a male’s body-hair “Frankly, it might be far more amusing — far cheaper, too — if California could forgo the recall and simply hire the Fab Five to remake the state. At the very least, they could corral the leading replacement candidates in a booth for a spray-on tan, then wax their eyebrows and manscape them senseless.” —Anita Creamer, "Sign us all up for our makeovers," Sacramento Bee, August 29, 2003 g) rural+urban>rurban- combining aspects of both urban and rural life The most reasonable conclusion is that we are all much of a muchness now — urban where it matters, but with rural aspirations if we can afford them. A new word — 'rurban' — has been coined to describe this condition. —David Nicholson-Lord, "To know the countryside, you must live in the city," New Statesman, May 10, 2004 The second group includes compounds. Although compounding used to be the favourite way of neologism-forming, nowadays it seems to have somewhat lost its popularity. Despite that fact, we can still find a fairly large number of compounds, the majority of which are nouns. As the examples prove, in most cases their structure is Adj+N, or N+N. Examples: h) fur+kid>furkid- a pet treated as if it were a child My name is Brenda Mejia and I'm owned by two Australian cattle dogs. I don't have kids, so I call my dogs my 'furkids.' They keep me as busy as a soccer mom. —Brenda Mejia, "Pet stories," The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA), April 30, 2004 i) moon+ rocket> moon rocket- a company with the price that rises dramatically after an initial public offering "Many venture-capital investors believe that out of a portfolio of ten investments, only two will be 'moon rockets'—ventures that produce a big payoff with a successful initial public offering." —Christine W. Letts, William Ryan, and Allen Grossman, "Virtuous Capital," Harvard Business Review j) stuck+holder>stuckholder- a person who owns a shares he can’t sell “Too bad more investors didn't heed those warnings, for on June 11 the SEC abruptly suspended trading of Net Command's shares, leaving thousands of gullible 'stuckholders' holding the bag at $15." —Christopher Byron, "Playing CyberFast and Loose With the Facts," TheStreet.com, June 17, 1999 In the example h) we have also encountered forms written hyphenated as fur-kid or, separated as fur kid, which proves the well known fact that when it comes to compounds rules for orthography are quite loose. In the example j) the word-creator used a pun, so the word stock was twisted into past 120 participle form of the verb stick stuck to name a particular type of people. Actually, stockholders turned into stuckholders. Although in the corpus I have collected and analyzed compound verbs were scarce, which proves a general tendency of English that compounding is not regarded as a highly productive process for verb-formation, the following two examples are provided for the sake of illustrativeness. Examples: k) data+fast> to datafast- to turn off one’s computer and spend some time away from any source of computer software and hardware l) kitchen+sink>to kitchen-sink – to announce all of company’s bad financial news at once In the example k) the compound verb has the structure N+V and therefore this is an endocentric compound, while in the example l) the verb to kitchen-sink is converted or back- formed from the compound noun of the same form, so it is not only an exocentric compound but a semantic neologism as well. A large number of neologisms belong to the group of derivatives, and as the example show both suffixation and prefixation are quite productive processes nowadays. Here I have tried to pay special attention to those neologisms which were derived by the means of what Crystal (1995:408) calls “morphological humor”. In other words some of those new derivatives manipulate the word structure or divide words into unusual places. Typical examples are all the neologisms derived by adding the ending –holic ( instead of English suffixes –lic, ic) which is the result of the word alcoholic being wrongly divided into alco- and – holic. Consequently, we can nowadays speak of various –holics such as : workaholic, chocoholic, shopaholic, surgiholic ( a person obsessed with plastic surgeries), milkaholic ( a person heavily addicted to drinking milk). Since it seems to be quite productive and accepted I cannot help but wonder if it is justified to give it a morpheme status? Similarly the word bibliography was wrongly cut into bib- and –liography and the noun Webliography ( a list of Web sites used), where an ending –liography was added to a noun Web, was made. However, not all the derived neologisms are formed with the “non-existing” affixes. Naturally, there are those in which well-established and accepted affixes were used, such as prefixes de-, un-, or a suffixes –ize and -cracy. Examples: m) de-+ policing > de-policing – a law-enforcement strategy in which police ignore some petty crimes in order to avoid some racial accusations. n) un- + decorate> undecorate- to redecorate a house or a room to give it a simpler look, especially after you have spent thousands on luxurious redecorating p) velocity+ -ize> velocitize – to cause a person to become used to a high speed “Safety experts argue that speeding has "velocitizing" effects on drivers, making it harder for them to slow down when conditions change and it's urgent to do so.” —"The mentality behind the wheel," The Oregonian, December 10, 2003 q) aggression+ -cracy>agressocracy- the society where aggression is a favourable way of behaving There is a growing number of neologisms made by adding the inflectional suffix –ing to nominal base, usually to denote an action. Marchand (1960: 303-305) mentions this suffix as the one primarily used with verbal bases, while its use with nominal bases was extremely popular in Old English. Since then a combination N+-ing was considered to be unproductive. Recent neologisms prove the contrary. Examples: r) blooding- in a criminal investigation, asking for DNA samples of a large number of people in the area where a crime has occurred 120 s) zorbing- a new kind of extreme sport in which a person is strapped inside a small sphere which is held within a larger sphere by a cushion of air, and then rolled down a hill t) togethering- vacationing with one’s extended family or friends Example t) shows how productive –ing is becoming as it was added to adverb together to form a noun. Apart from blending, derivation and compounding neologisms are also formed by all the mechanisms of shortening. Being easy to make and remember, acronyms and clippings are still extremely popular. Examples: u) MVVD- male vertical volume drinker v) PoMosexual< postmodern + sexual- a person who shuns any labels which define people according to their sexuality. All the above mentioned neologisms are a marvelous example and proof of dynamic life that the English language leads trying to adapt to new demands put a modern society imposes on it. In order to achieve that the speakers of English, be them native speakers or those who speak it as a second language, are exploiting all the possible and sometimes “impossible” methods and mechanisms. Neologisms more than any other aspect of English represent how endless and unpredictable human creativity and skill at the same time showing us that new-words formation may be as adrenaline raising as zorbing. References: Bauer, L, English Word-Formation ,London, 1983 ________, Introducing Linguistic Morphology, London, 1988 Crystal David, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, Cambridge, 1995 Leech, G.N., A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry, London, 1969 Mc Fedries, P., Word Spy: The Word Lover’s Guide to Modern Culture,New York, 2004 Pei, M. ,Glossary of Linguistic Terminology, New York, 1966 120