Chapter 6: Court Procedures and Compensation

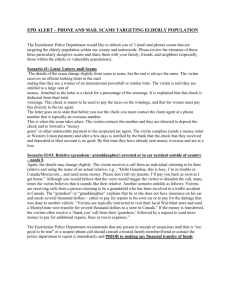

advertisement