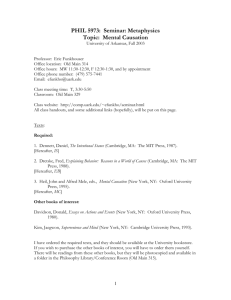

Reply to Jaegwon Kim on Mental Causation

advertisement

1 Reply to Jaegwon Kim on Mental Causation August 11, 2003 Dear Jaegwon, I have just read a piece by you in which you criticize some views of mine and challenge me in interesting ways. (This is on page 47-50 in “The Many Problems of Mental Causation.”) I respect your opinions so I am going to respond to your criticisms. First of all, in describing my views (p.49) you shift almost imperceptibly from my terminology where I talk about different “levels” of a “system”, and to your terminology where you claim I am offering “descriptions of the same situation.” I don’t recall using “situation,” and it doesn’t sound like me. I prefer “system.” This shift is important because the next move you make is from “situation” to “phenomenon;” and then it turns out that you are going to use this to try to saddle me with some kind of reductionist identity claim, “pain = neuron firings.” But that is a distortion of my views. So what is the right way not only to interpret me, but the right way to tell the truth? Well, here goes. The first step is, as always, to forget all about philosophy with its incoherent terminology, its great traditional mistakes and obsolete categories. The first step in short is to describe the facts. You make it impossible to do this at the very beginning where you ask, “How is it possible for the mind to exercise its causal powers in a world that is fundamentally physical?” (p.30). But this way of posing the question accepts the obsolete distinction of mental and physical that we need to overcome and accepting that distinction that makes it impossible for you to hear my answer. So let’s give a description that avoids the old mistakes. Here is such a description. The brain, like any other organ or piece of machinery, is a system; and like any system it has different levels of description. Pains are at a higher level and neuron firings at a lower level. To get clear about different levels of description of a system, consider a much simpler system. Compare the brain with a hammer used to drive a nail. The hammer also has different levels of description. The hardness (solidity) of the hammer 2 head is at a higher level, the molecule movements at a lower level. When systems function causally the different levels function causally, but typically they are different levels of the same causal system and not different causes. Thus when the hammer drives the nail, the solidity of the hammer head functions causally at the higher level when it hits the nail, but at the lower level the molecules in the hammer head transfer energy to the molecules in the nail. This does not imply either that there is overdetermination (that the movement of the nail has two independent sets of causes or that solidity is epiphenomenal (that it is causally irrelevant). Furthermore the hardness of the hammer head is explained causally by the behavior of the molecules. This is a typical form of “bottom up” causation where a higher level feature of a system is explained by the behavior of the lower level elements of which the system is composed. Now with these points in mind, the existence of causally real levels within a system and the existence of bottom up forms of causal explanation, let us state some uncontroversial facts about how pains function causally. First fact: I have a pain, a headache, and this pain is a higher level feature of my brain. At a lower level of the same system there are massive neurons firings in my brain, NP. The neuron firings cause the pain by bottom up causation of the sort we found in the hammer example. I describe this fact by saying that the pain is caused by neuronal processes and realized in the neuronal system. (I think your commitment to a Humean analysis of causation makes it hard to accept these facts, so it’s okay with me if you say that the pain is explained by neuronal processes. It makes no difference) Second fact. The pain, together with desires and beliefs, causes me to have a desire for aspirin. This is left right event causation across time. The pain at t1 (along with beliefs and desires) causes the desire at t2. Philosophers have inherited a lot of mistakes from Hume and one of the favorites is to suppose that all causation must be left right causation across time. Third fact: My desire is itself caused by lower-level neuron firings in the brain, NP*. Just as the pain was caused by neuronal processes while realized in the system of neurons, so with the desire. You could not have a conscious desire unless it was caused by neuron firings and the desire can only exist if it is realized in the neuronal system. 3 Fourth fact: At lower level description of the system NP causes NP*. Left right causation across time. The higher level features function causally because they are features of a system of lower level elements functioning causally. Notice that we are not talking about two causes, but one system of causation described at different levels. And we could keep going on down to the level of quarks and muons. In neither the hammer case nor the brain does this set of formal relations imply either causal overdetermination or epiphenomenalism, because the lower level causes are not separate causes but the same causes described at a lower level of the system. . Notice that the description that I have given is totally unproblematic as long as we stay away from the traditional philosophical categories. Now why do we have problems about the “mental” cases that we do not have in the hammer case? Well first in the hammer case, we typically carve off the surface features and redefine the notions in terms of the causes of the surface features. That is, on the basis of the causal reduction we make an ontological reduction. We go from “solidity is caused by molecular behavior” to “solidity just is molecular behavior”. We are reluctant to do this with pains because the whole point of having the concept is to name the first person ontology, the what-it-feels-like aspect of pains. So in the case of pains the causal reduction does not lead to an ontological reduction. The appearance that there is an especially difficult philosophical problem seems to me the result of a series of confusions. I believe there are four sets of confusions. 1. Confusion about causation. Apparently you have a problem about bottom up causation, but it is absolutely common in nature. It is an old philosophical mistake, and as I said, we can blame Hume for it, to suppose that all causation must be event causation going left to right through time and covered by a causal law. I still find it hard to believe that anybody believes that mythology but there it is and I suppose it is still common. But non Humean, non event causation is very common in nature. Ask yourself, “What causes this desk to exert pressure on the floor?” Answer: gravity. But gravity is not another event. It is a permanent force operating in nature. I could multiply examples indefinitely but there is no question that this is such a case. Or if you like, more typical cases are bottom up 4 causation where you move from the micro to the macro. Ask yourself, “Why does this table exhibit the features of solidity?” That is, for example, it supports objects, it is impenetrable by other objects, etc. And the answer of course is that the molecule movements causally explain the surface feature of solidity. The cause and effect are simultaneous and indeed, they are like consciousness in the brain, different levels of description of the same system. The form of these relationships, to repeat, is very common in nature. 2. A second confusion is about identity. There are actually several different kinds of identity statements. The philosophers’ favorite is the one that asserts the identity of a material object with itself. Mark Twain = Samuel Clemens, for example. Or The Evening Star= The Morning Star. Another favorite is identity of composition. The water is identical with H2O molecules, because water is composed of H20 molecules. Event identity is much trickier than either of these, not only because (like objects) the same event can have so many different descriptions but, even more importantly, events have less clear boundaries than material objects. The event of my walking around in room 50 Birge from 12 to 1 is identical with my giving a lecture in 50 Birge from 12 to1, because I walk around while I lecture. So, is the event of my feeling a pain identical with the event of neuron firings? The question is ill-defined. Here is one interpretation: Can we introduce the notion of an event big enough to be described both as my feeling a pain, and such and such neurons firing? If you phrase the question that way, the answer is yes, of course. It is no more problematic to describe a single event as feeling a pain and neurons firing than describing a single event as me walking and me lecturing. But in this large sense the identity pain = neuron firings is no use to the identity theorists, because that identity leaves us with an irreducibile first person ontology as part of the event and the whole idea of the identity theory was to defend materialism and reject any irreducible mental component. The identity theory was part of a reductionist program. They wanted being a pain just to be neurons firing and nothing more (nothing “over and above” in the jargon of the time). But event identity big enough to state the truth won’t give you that reduction (compare: the identity of the event of my walking with the event of my lecturing does not make walking into 5 lecturing). The point of the reduction was to give a materialist solution to the mind-body problem that would show that there was no irreducible first person ontology. But our identity, pain =neuron firings, does not give this result, because the event in question still has both first person and third person properties. In the case of consciousness, unlike say, solidity, the causal reduction does not lead to an ontological reduction, and that leads to the next point. 3. Third confusion: Reduction. Just as there are many different kinds of identity statements so there many different kinds of reductions. Typically a causal reduction leads to ontological reduction, because we redefine the reduced phenomenon into its causal basis. But you can't do this with consciousness and the brain because you can't do a reduction of a first person ontology into a third person ontology. But so what? The pain isn't something "over and above" its neural basis, even though it is not ontologically reducible to its neuronal bases. There are no causal powers of the pain that are not causal powers of the neural structure, because the pain is just a state that the structure is in. 4. Fourth confusion: Dualism. Because the first person ontology is not ontologically reduced to a third person ontology we are tempted to think that there must be some kind of dualist ontology leftover, that pains, etc. might be real though epiphenomenal, that the immaterial pain is in a different ontological category from the material brain, that it is something “over and above” brain processes. But of course that is a massive mistake. The bottom line of this entire discussion is that if we forget all about the traditional philosophical categories with their massive confusions, due mostly to Descartes and Hume, then the problems have a rather easy solution. In short, it seems to me that your objections to me are based not on any real dispute about the facts or even in understanding the facts, but rather on your acceptance of the traditional philosophical categories.