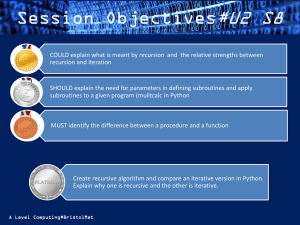

Recursion

advertisement

533554356

-1-

Chapter 6

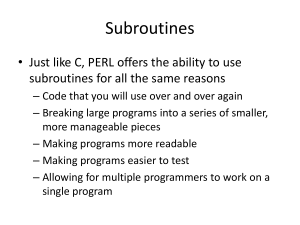

Subroutines in Perl

Built-in Math Functions

User defined Subroutines

Argument Lists

Returning values

Other Ways to invoke a subroutine

Random number generation

Recursion

Scope Rules: Global, Lexical and Dynamic

Namespaces, Packages and Modules

Pragmas

533554356

-2-

Built in functions/subroutines and user defined functions/subroutines

Built in function are functions that are part of the Perl programming environment

The unix command man perlfunc or perldoc perlfunc on other systems allow

you to view the documentation of Perl functions.

The programmer can write her/her own subroutines. Each subroutine should

perform a single task – ( functional cohesion )

Built in Math functions ( pg. 174)

Built in math library functions allow the programmer to perform common mathematical

calculations.

$result = sqrt ( 900 );

Arguments to the function can be scalars, hashes, arrays or expressions.

#!/usr/bin/perl

# Fig. 6.3: fig06_03.pl

# Demonstrating some math functions.

$_ = -2;

print "Absolute value of 5 is: ", abs( 5 ), "\n",

"Absolute value of -5 is: ", abs( -5 ), "\n",

"Absolute value of $_: ", abs, "\n\n";

print "exp( $_ ): ", exp, "\n";

print "log( 5 ): ", log( 5 ), "\n";

print "sqrt( 16 ): ", sqrt( 16 ), "\n";

Output:

Absolute value of 5 is: 5

Absolute value of –5 is: 5

Absolute value of –2: 2

exp( -2 ): 0.135335283236613

log( 5): 1.60943769124341

sqrt(16 ): 4

533554356

-3-

#!/usr/bin/perl

# Fig 6.4: fig06_04.pl

# User-defined subroutines that take no arguments.

subroutine1(); # call the subroutine with no arguments

subroutine2(); # call the subroutine with no arguments

# the code after this comment executes only if the program

# explicitly calls (or invokes) these subroutines (as in lines 5 and 6).

sub subroutine1

{

print "called subroutine1\n";

}

sub subroutine2

{

print "called subroutine2\n";

}

Output:

called subroutine1

called subroutine2

Argument List

#!/usr/bin/perl Fig 6.5: fig06_05.pl

# Demonstrating a subroutine that receives arguments.

displayArguments( "Sam", "Jones", 2, 15, 73, 2.79 );

# output the subroutine arguments using special variable @_

sub displayArguments

{

# the following statement displays all the arguments

print "All arguments: @_\n";

# uses special array variable @_

# the following loop displays each individual argument

for ( $i = 0; $i < @_; ++$i ) {

# accesses each element in the array @_– no relationship to $_ special variable

print "Argument $i: $_[ $i ]\n";

}

}

533554356

-4-

Output:

All arguments: Sam Jones 2 15 73 2.79

Argument 0: Sam

Argument 1: Jones

Argument 2: 2

Argument3: 15

Argument4: 73

Argument5: 2.79

@_ displays each argument separated by a space

@_ flattens all arrays and hashes. It will contain one list with all the data from the array

and the scalar value. A hash is flattened into a list of its key/value pairs.

( @first, $second ) = @_;

@first will take all the data and $second will be undefined.

The subroutine displayArguments can receive any number or arguments.

533554356

-5Returning values

A subroutine returns a value using the return keyword.

#!/usr/bin/perl

# Fig 6.7: fig06_07.pl

# Demonstrating a subroutine that returns a scalar or a list.

# call scalarOrList() in list context to initialize @array, then print the list

@array = scalarOrList(); # list context to initialize @array

$" = "\n";

# set default separator character – special variable $”

# specifies what will be printed between values in array

# when an array is printed in double quotes “”

print "Returned:\n@array\n";

# call scalarOrList() in scalar context and concatenate the

# result to another string

print "\nReturned: " . scalarOrList(); # scalar context

# use wantarray to return a list or scalar

# based on the calling context

sub scalarOrList

{

if ( wantarray() ) { # if list context

return 'this', 'is', 'a', 'list', 'of', 'strings';

}

else {

# if scalar context

return 'hello';

}

}

Output:

returned:

this

is

a

list

of

strings

Returned: hello

533554356

-6-

Other ways to call a subroutine: (Page 181)

&subroutine1;

# prefix & calls subroutine1

Using this syntax the parenthesis can be omitted it there are no arguments or if the

subroutine the default arguments in @_

Parenthesis are always required if explicit arguments are passed

Another syntax is for calling subroutines is the bareword.

subroutine1;

In this case, if the subroutine is defined before the line executed the subroutine will be

called. If it is not defined - the subroutine is not called and the call is interpreted as a

string. I the subroutine would return something the string would be interpreted as the

return value.

533554356

-7-

#!usr/bin/perl Fig 6.8: fig06_08.pl

# Syntax for calling a subroutine.

# subroutine with no arguments defined before it is used

sub definedBeforeWithoutArguments

{

print "definedBeforeWithoutArguments\n";

}

# subroutine with arguments defined before it is used

sub definedBeforeWithArguments

{

print "definedBeforeWithArguments: @_\n";

}

# calling subroutines that are defined before use

print "------------------------------\n";

print "Subroutines defined before use\n";

print "------------------------------\n";

print "Using & and ():\n";

&definedBeforeWithoutArguments();

&definedBeforeWithArguments( 1, 2, 3 );

print "\nUsing only ():\n";

definedBeforeWithoutArguments();

definedBeforeWithArguments( 1, 2, 3 );

print "\nUsing only &:\n";

&definedBeforeWithoutArguments;

print "\"&definedBeforeWithArguments 1, 2, 3\"", " generates a syntax error\n";

print "\nUsing bareword:\n";

definedBeforeWithoutArguments;

definedBeforeWithArguments 1, 2, 3;

# calling subroutines that are not defined before use

print "\n-----------------------------\n";

print "Subroutines defined after use\n";

print "-----------------------------\n";

print "Using & and ():\n";

&definedAfterWithoutArguments();

&definedAfterWithArguments( 1, 2, 3 );

print "\nUsing only ():\n";

definedAfterWithoutArguments();

definedAfterWithArguments( 1, 2, 3 );

533554356

-8-

print "\nUsing only &:\n";

&definedAfterWithoutArguments;

print "\"&definedAfterWithArguments 1, 2, 3\"", " generates a syntax error\n";

print "\nUsing bareword:\n";

definedAfterWithoutArguments;

print "\"definedAfterWithoutArguments\" causes no action\n";

print "\"definedAfterWithArguments 1, 2, 3\"", " generates a syntax error\n";

# subroutine with no arguments defined after it is used

sub definedAfterWithoutArguments

{

print "definedAfterWithoutArguments\n";

}

# subroutine with arguments defined after it is used

sub definedAfterWithArguments

{

print "definedAfterWithArguments: @_\n";

}

533554356

-9-

Output:

-----------------------------Subroutines defined before use

-----------------------------Using & and ():

definedBeforeWithoutArguments

definedBeforeWithArguments: 1 2 3

Using only ():

definedBeforeWithoutArguments

definedBeforeWithArguments: 1 2 3

Using only &:

definedBeforeWithoutArguments

"&definedBeforeWithArguments 1, 2, 3" generates a syntax error

Using bareword:

definedBeforeWithoutArguments

definedBeforeWithArguments: 1 2 3

----------------------------Subroutines defined after use

----------------------------Using & and ():

definedAfterWithoutArguments

definedAfterWithArguments: 1 2 3

Using only ():

definedAfterWithoutArguments

definedAfterWithArguments: 1 2 3

Using only &:

definedAfterWithoutArguments

"&definedAfterWithArguments 1, 2, 3" generates a syntax error

Using bareword:

"definedAfterWithoutArguments" causes no action

"definedAfterWithArguments 1, 2, 3" generates a syntax error

533554356

- 10 Random Number Generation

rand

the function rand will generate a floating-point scalar value greater than or

equal to 0

$i = rand( );

to set the range we can pass the function an argument.

1 + int ( rand ( 6 ) )

using 1 as the shift value and 6 as the scale factor would

produce a number in the range from 1 to 6 by adding 1 to the result.

Otherwise the range would have been 0 to 5.

srand

the function srand lets the system determine seed. It courses the system to

read the system clock to obtain the value for the seed. You can pass an

argument to the function and work with different seeds.

If the function is used it needs only to be called once in the program.

533554356

- 11 -

Recursion

A recursive subroutine is a subroutine that calls itself either directly or through another

subroutine.

#!/usr/bin/perl

# Fig 6.13: fig06_13.pl

# Recursive factorial subroutine

# call function factorial for each of the numbers from

# 0 through 10 and display the results

foreach ( 0 .. 4 ) {

print "$_! = " . factorial( $_ ) . "\n";

}

# factorial recursively calculates the factorial of the argument it receives

sub factorial

{

my $number = shift; # get the argument

if ( $number <= 1 ) { # base case

return 1;

}

else {

# recursive step

return $number * factorial( $number - 1 );

}

}

0! = 1

1! = 1

2! = 2

3! = 6

4! = 24

Recursion and iteration – Any recursive algorithm can be coded as an iteration.

To examine whether to use recursion or iteration you can draw the recursion tree.

If the tree is linear it is more efficient to use iteration.

If the tree is balanced ( an no duplicate work is performed ) recursion could be used.

533554356

- 12 Scope Rules: Global, Lexical and Dynamic

An identifier’s scope is the portion of the program in which the identifier can be

referenced.

Three scopes for an identifier are:

Global scope, lexical scope and dynamic scope.

Global Scope:

An identifier of global scope can be used throughout the program. For example:

All global variables have global scope.

Variables identified without any keyword prefix are automatically of global scope

The prefix our can be used to explicitly define global variables

Lexical Scope:

A lexical scope variable is a variable that exists only during the block in which it

was defined.

Prefix: my

Dynamic Scope:

A variable of dynamic scope is one that exists from the time it is created until the

end of the block in which it was created. Such a variable is accessible both in the block

in which it is defined and to any other subroutine called from that block.

Prefix: local

Lexical and dynamic variables always hide ( but do not destroy) global variables of the

same name.

533554356

- 13 -

#!/usr/bin/perl Fig. 6.16: fig06_16.pl Demonstrating variable scope.

# before global variables are defined, call subroutine1

print "Without globals:\n";

subroutine1();

# define global variables

our $x = 7;

our $y = 17;

# call subroutine1 to see results with defined global variables

print "\nWith globals:";

print "\nglobal \$x: $x";

print "\nglobal \$y: $y\n";

subroutine1();

print "\nglobal \$x: $x";

print "\nglobal \$y: $y\n";

subroutine2();

# subroutine1 displays its own $x (lexical scope )

# and $y (dynamic scope) variables, then calls subroutine2

sub subroutine1{

my $x = 10;

local $y = 5;

print "\$x in subroutine1: $x\t(lexical to subroutine1)\n";

print "\$y in subroutine1: $y\t(dynamic to subroutine1)\n";

subroutine2();

}

# subroutine2 displays global $x and subroutine1's $y which has dynamic scope

sub subroutine2

{

print "\$x in subroutine2: $x\t(global)\n";

print "\$y in subroutine2: $y\t(dynamic to subroutine1)\n";

}

Without globals:

$x in subroutine1: 10

$y in subroutine1: 5

$x in subroutine2:

$y in subroutine2: 5

(lexical to subroutine1)

(dynamic to subroutine1)

(global)

(dynamic to subroutine1)

With globals:

global $x: 7

global $y: 17

$x in subroutine1: 10

$y in subroutine1: 5

$x in subroutine2: 7

$y in subroutine2: 5

(lexical to subroutine1)

(dynamic to subroutine1)

(global)

(dynamic to subroutine1)

global $x: 7

global $y: 17

$x in subroutine2: 7

$y in subroutine2: 17

(global)

(dynamic to subroutine1)

533554356

- 14 Namespaces, Packages, and Modules

Perl uses packages ( or namespaces) to determine the accessibility of variables and

subroutine identifiers.

Perl’s scooping rules derive from the package concept.

Each Package has its own symbol table – containing the variables and subroutine names

By default, the global variables and subroutines are part of the main package symbol

table – Perl’s global variables are not true global variables (they are package global

variables, or package variables).

The main package is the default package

Lexical variables – are not part of the symbol table. Each block has its own temporary

storage for lexical variables known as the scratchpad.

A symbol table is a hash that identifies the key (variable) and the value ( address ) of the

variable.

Thus, variable names have to be unique except when they are of different types

( scalar vs. array for example).

533554356

- 15 -

Defining a package and importing it with require

If no package is specified the name of the current package is the default package main

The programmer can change that with the package statement.

Creating a new package causes perl to create a new symbol table.

Normally there is one package per sourcefile. If a program contains two or more

packages each package contains its own unique set of identifiers.

require

is the keyword that tells Perl to locate a package and add it to the program.

.pm is optional – Perl assumes .pm filename extension. Ex:

require

firstPackage;

Perl looks for the file in the current directory – if it cannot find it it

Searches the directories that are named in a special built in array

@INC which contains the directories for the Perl library on the computer.

Packages using require are loaded during the execution phase

::

The :: is the scope resolution operator – it ties the variable on the right to

the package (scope) identified on the left of the ::

533554356

- 16 -

#!usr/bin/perlFig 6.17: fig06_17.pl Demonstrating packages.

# make FirstPackage.pm available to this program

require FirstPackage;

# define a package global variable in this program

our $variable = "happy";

# display values from the main package

print "From main package:\n";

print "\$variable = $variable\n";

print "\$main::variable = $main::variable\n";

# display values from FirstPackage

print "\nFrom FirstPackage:\n";

print "\$FirstPackage::variable = $FirstPackage::variable\n";

print "\$FirstPackage::secret = $FirstPackage::secret\n";

# use a subroutine in FirstPackage to display the

# values of the variables in that package

FirstPackage::displayFirstPackageVariables();

From main package:

$variable = happy

$main::variable = happy

From firstPackage:

$FirstPackage::variable = birthday

$FirstPackage::secret =

$variable in displayFirstPackagevariables = birthday

$secret in displayFirstPackageVariables = new year

533554356

- 17 -

#!usr/bin/perl Fig 6.18: FirstPackage.pm Our first package.

package FirstPackage; # name the pacakge/namespace

# define a package global variable

our $variable = "birthday";

# define a variable known only to this package

my $secret = "new year";

# subroutine that displays the values of the variables in FirstPackage

sub displayFirstPackageVariables

{

print "\$variable in displayFirstPackageVariables = ", $variable, "\n";

print "\$secret in displayFirstPackageVariables = ", $secret, "\n";

}

533554356

- 18 -

Modules and the use Statement - A module is a package providing the user more

control on how to reference identifies in the module’s package.

use

- is a statement that imports modules and packages at compile time and

the identifiers of the module are available to the program.

- Another advantage is that the compiler can tell us if the package is

available at compile time as opposed to execution time

#!/usr/bin/perl Fig 6.19: fig06_19.pl program to use our first module

use FirstModule; # import identifiers from another package

print "Using automatically imported names:\n";

print "\@array contains: @array\n"; # @FirstModule::array

greeting();

# FirstModule::greeting

Output:

Using automatically imported names:

@array contains: 1 2 3

Modules are handy!

#!/usr/bin/perl Fig 6.20: FirstModule.pm - Our first module.

package FirstModule;

# the following two lines allow this module to export its

# identifiers for use in other files.

use Exporter;

# use module Exporter

our @ISA = qw( Exporter ); # this module "is an" Exporter

# @array and &greeting are imported automatically into a

# file that uses this module

our @EXPORT = qw( @array &greeting );

# define identifiers for use in other files

our @array = ( 1, 2, 3 );

sub greeting

{

print "Modules are handy!";

}

return 1; # indicate successful import of module

533554356

- 19 -

Pragmas - Perl pragmas are statements that the compiler uses to set compiler options.

use strict;

use strict ‘subs’;

use strict ‘vars’;

use vars qw(variable1 variable2 variable2) ;

using use strict makes programs easier to maintain and debug. When using use strict

Perl checks each variable to make sure it is fully qualified,. There are four ways use

strict can be satisfied:

a) use the my keyword for lexical scope – then you can use their short name

throughout the block in which they are defined

b) use our keyword - package variables defined with our keyword are placed in

the symbol table. They can be accessed with their short name throughout the

package. Outside the package they must be accessed with their fully qualified

name.

c) variables can be used with their fully qualified name in all instances.

Including in the package in which they are defined. $main::variable

d) a program can specify a use vars statement followed by a list containing the

names of variables

use vars qw( variable1 variable2 variable3 );

use warnings;

This pragma warns the user of possible typos, the use of uninitialized variables,

and other problems in the code.

no strict;

no warning;

Turns off strict and warnings. If used inside a block it turns off the strict and

warning until the end of the block.

Named constants:

use constant PI => 3.14159;

use diagnostics;

provides detailed error messages.

enable()

disable()

these command toggle diagnostics on and off during program execution.

use integer;

tells the compiler to perform all arithmetic operations as integer

operations.