Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

1

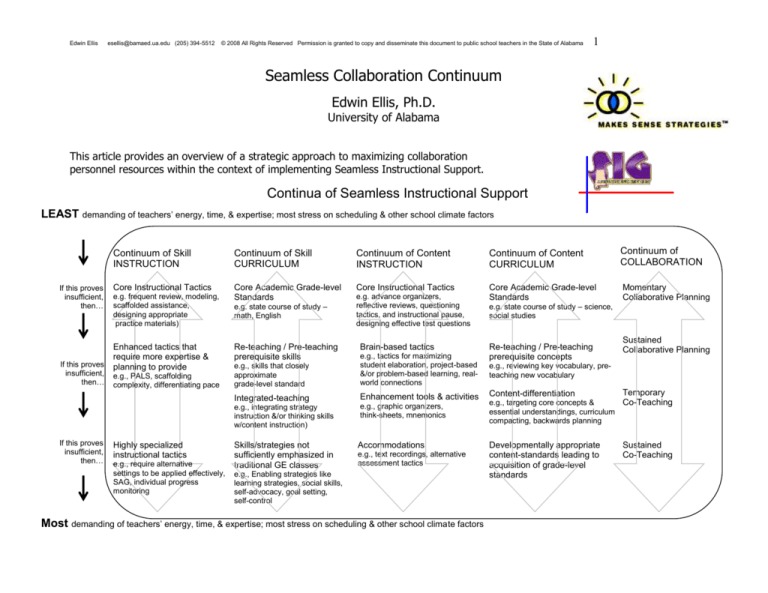

Seamless Collaboration Continuum

Edwin Ellis, Ph.D.

University of Alabama

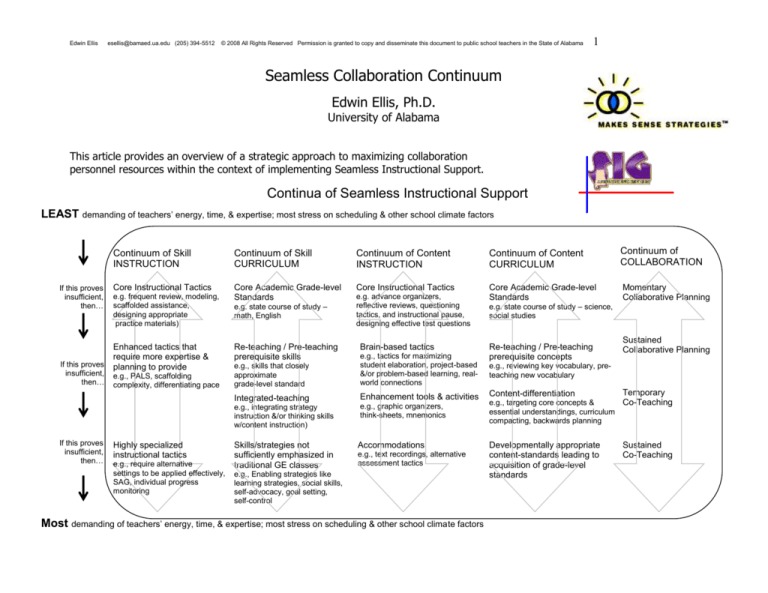

This article provides an overview of a strategic approach to maximizing collaboration

personnel resources within the context of implementing Seamless Instructional Support.

Continua of Seamless Instructional Support

LEAST demanding of teachers’ energy, time, & expertise; most stress on scheduling & other school climate factors

If this proves

insufficient,

then…

If this proves

insufficient,

then…

If this proves

insufficient,

then…

Continuum of Skill

INSTRUCTION

Continuum of Skill

CURRICULUM

Continuum of Content

INSTRUCTION

Continuum of Content

CURRICULUM

Continuum of

COLLABORATION

Core Instructional Tactics

Core Academic Grade-level

Standards

Core Instructional Tactics

Core Academic Grade-level

Standards

Momentary

Collaborative Planning

e.g. frequent review, modeling,

scaffolded assistance,

designing appropriate

practice materials)

Enhanced tactics that

require more expertise &

planning to provide

e.g., PALS, scaffolding

complexity, differentiating pace

Highly specialized

instructional tactics

e.g., require alternative

settings to be applied effectively,

SAG, individual progress

monitoring

e.g. state course of study –

math, English

Re-teaching / Pre-teaching

prerequisite skills

e.g. advance organizers,

reflective reviews, questioning

tactics, and instructional pause,

designing effective test questions

Brain-based tactics

e.g., skills that closely

approximate

grade-level standard

e.g., tactics for maximizing

student elaboration, project-based

&/or problem-based learning, realworld connections

Integrated-teaching

Enhancement tools & activities

e.g., integrating strategy

instruction &/or thinking skills

w/content instruction)

e.g., graphic organizers,

think-sheets, mnemonics

Skills/strategies not

sufficiently emphasized in

traditional GE classes

Accommodations

e.g., text recordings, alternative

assessment tactics

e.g., Enabling strategies like

learning strategies, social skills,

self-advocacy, goal setting,

self-control

Most demanding of teachers’ energy, time, & expertise; most stress on scheduling & other school climate factors

e.g. state course of study – science,

social studies

Re-teaching / Pre-teaching

prerequisite concepts

Sustained

Collaborative Planning

e.g., reviewing key vocabulary, preteaching new vocabulary

Content-differentiation

Temporary

Co-Teaching

e.g., targeting core concepts &

essential understandings, curriculum

compacting, backwards planning

Developmentally appropriate

content-standards leading to

acquisition of grade-level

standards

Sustained

Co-Teaching

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

2

Seamless Instructional Support

(SIS) arranges instructional

tactics and services into a

continuum for providing

interventions for all students

who are not responding

adequately to traditional

instruction. Instructional

support is provided via a system

of layered support, with each

layer reflecting increasingly

more intensive instruction, more

sophisticated instructional tools,

adjustments in curriculum, and

in the nature and extent of

collaboration that occurs among

professionals on the student’s

behalf (see Figure 1). The intent

is to provide a proactive

approach to providing support

across a continuum of services

that reflect a least-to-most

intensive, least-to-most

intrusive, least-to-most

demanding of teachers’ time

and energy, and divergentfrom-normal-to-rarely-used

forms of support.

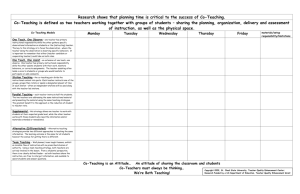

There are a range of collaborative processes that fall on a continuum of relatively simple-to-use to those that are complex and

require significant amounts of expertise, time, and teacher-energy to use. Likewise, when considering the long-term impact of GE/SE

collaboration, a growing body of research suggests that some processes have greater impact than others have, and thus are more

cost effective and efficient. Just as it makes little sense to attempt to use complex interventions that demand more expertise, time,

and effort to employ before ensuring that students are receiving the essentials of pedagogy, it likewise makes little sense to employ

applications of GE/SE collaboration that also require greater expertise, time, and energy to employ before attempting less intensive,

but potentially more effective and efficient collaborative processes.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

3

Momentary Collaborative Planning

GE and SE teachers meet on an as-needed basis to collaborate to solve student issues as they arise. These meetings are typically

informal and overlap with other activities (i.e., GE/SE teachers eat lunch together; discuss the needs of a specific student). Much of

the interaction involves a verbal discussion of a student’s issue and exchange of ideas or suggestions; activities that require

sustained time to meet

and work (e.g., codeveloping units or lesson

plans, designing contentenhancements) are usually

not engaged in at this

level.

Momentary Collaborative

Planning is often very costeffective and allows SE

teachers the greatest

flexibility to work with the

greatest range of teachers

within a building, and it

requires the least amount

of time to employ

effectively.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

4

Generally, GE teachers who engage in Momentary Collaborative Planning are already experienced and skilled at providing

instructional supports. Thus, this level of collaboration often involves little more than sharing of ideas. Due to the existing level of GE

teacher expertise, little is needed in terms of teaching him/her how to implement a procedure. They can often take an idea and “run

with it.”

Sustained Collaborative Planning is most beneficial to teachers who are generally less knowledgeable about techniques for

differentiating curriculum and instruction, and they require more assistance while learning how to implement a new technique.

Sustained Collaborative Planning

GE and SE teachers meet on a regularly scheduled basis to (i) address the needs of specific students and to review, refine, and/or

revise on-going strategies employed to meet these needs; and (ii) to engage in the co-development of units, lesson plans, content

enhancements,

accommodations,

assessments,

behavior plans, and

other kinds of

instructional supports

that are best

designed

collaboratively. Here,

Momentary

the content-expertise

Collaborative

of the GE teacher,

Planning

combined with the

instructional

strategies expertise of

the SE teacher, are

utilized to plan GE

teacher-provided

instruction that

employs strategies

sufficiently robust to

impact students atrisk, but also

appropriate for all

students.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

5

GE teachers who benefit most from this form of collaboration that those who:

Are responsible for teaching students at-risk who, given sufficient instructional support (e.g., use of content enhancements,

accommodations) tend to be successful learning grade-level standards.

Teach subject-area classes composed of students reflecting a wide range of abilities.

Are relatively inexperienced or have relatively limited knowledge of strategies for differentiating curriculum or differentiating

instruction.

This form of collaboration requires sufficient time for teachers to work together; thus, successful use of this model requires that

administrators proactively create and protect the time needed for teachers to engage in this form of work.

Use of Sustained Collaborative Planning over time serves as a form of professional development for participating GE teachers; thus,

the more it is employed with a given GE teacher, the more sophisticated this teacher becomes about instructional support strategies,

and in turn, the less need this teacher has for this kind of collaboration.

Since Sustained Collaborative Planning occurs on a regularly scheduled basis, more constraints are placed on the flexibility of SE

teachers to support a wide range of teachers, and as such, SE teachers impact the teaching of fewer teachers within a building.

GE and SE teachers engaging in Sustained Collaborative Planning may occasionally decide that Temporary Co-Teaching of specific

lessons or a unit is necessary.

Temporary Co-Teaching

Here, GE and SE teachers engage in team-teaching a lesson, a series of lessons, or in some cases, even a unit of study, but it occurs

only on a temporary basis; that is, once the lesson(s) or unit has been completed, the team-teaching arrangement ceases.

An important purpose of Temporary Co-Teaching is to provide the GE teacher with peer coaching in the use of a specific instructional

support strategy. Here, the SE teacher might model how a strategy is applied when teaching the GE teacher’s class, and then

support the GE teacher as s/he practices using it with the class.

Another purpose is to temporarily provide an additional teacher in the classroom when a predictably complex subject or skill is being

taught so that more student-assistance is available when needed. For example, an Algebra teacher may be anticipating that her class

will have trouble understanding the concept of “binomials,” so for just this lesson, the SE teacher becomes a second teacher in the

class to ensure that all of the students understand the concept. Once this lesson is complete, the team-teaching arrangement ceases

until the next time an extra teacher is needed.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

6

GE teachers who benefit most from this form of collaboration are those that:

Need additional support beyond the collaborative planning of lessons or units. These teachers greatly benefit from observing

others using an instructional strategy, and in particular, from observing how it is used with her/his own students. These

teachers also greatly benefit from having others coach their use of the techniques.

- AND/OR Need additional teachers in the classroom to ensure that students understand a complex concept or skill.

Momentary

Collaborative

Planning

This model of

collaboration places

greater constraints

on SE teachers’ time,

thus teachers who

provide these

services are less able

to support as many

GE teachers in the

building.

There are several

common models of

co-teaching; some

are best reserved for

use in sustained coteaching situations

(see below). Some,

however, can work

effectively in either

temporary or

sustained coteaching

arrangements.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

7

Sustained Co-Teaching

The greater the diversity of student ability in a given class, the more value a team-teaching approach has. There is a critical point

where a single teacher, no matter how energetic or skillful s/he is, can no longer effectively address a wide range of student needs,

particularly if the students are adolescents. Sustained Co-Teaching features GE and SE teachers who co-teach a class, or series of

classes, for a sustained period (i.e., semester, year, or multiple years). The GE and SE teachers co-plan and co-teach lessons for

these classes in an on-going manner.

A positive benefit of

the sustained CoTeaching is that, over

time, teachers

discover and

capitalize on the

strengths of their

teaching partner.

Students are exposed

Momentary

to the best of what

Collaborative

each educator brings

Planning

to the table. Clearly,

both teachers gain

expertise from the

sustained co-teaching

experience and

students in these

classes potentially

greatly benefit from

the extra teacher

availability. The

downside, however is

that use of this model

severely restricts the

SE teacher’s

availability to work

with other teachers

to enable them to

provide instructional

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

8

support to students who need it. This form of GE/SE collaboration is most cost effective when it is reserved for use in classes

populated by a significant number of at-risk students (e.g., a third of the class).

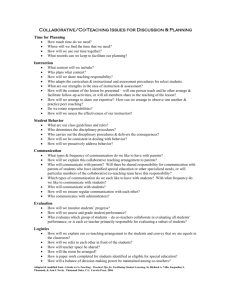

KEY POINTS TO CONSIDER

COLLABORATION in the context of teaching Skills

There are no real compromises to providing developmentally appropriate skill instruction

because acquisition of advanced skills is so highly dependent on prior acquisition of

requisite knowledge and skills. Thus, collaborative efforts pertaining to skill instruction

should focus on:

(i)

Specifying requisite knowledge associated with soon-to-be-taught

information;

(ii)

Specifying pertinent developmental levels of students relative to the to-betaught information;

(iii)

Understanding why specific students are not performing commensurate with

their typical achieving peers in these specific areas,

(iv)

Designing developmentally appropriate instruction for them, including…

Determining ways of providing ability-group instruction,

Ensuring that students are receiving the elements of essential pedagogy (e.g.,

advance & post organizers, making steps to skill explicit, scaffolded assistance,

scaffolded complexity of skill, clear and explicit feedback)

Ensuring students receive sufficient correct practice of the skills.

One of the greatest obstacles to

providing developmentally

appropriate instruction in widely

diverse-ability classes is the time,

energy, opportunity and expertise

required to provide this kind of

instruction, especially when the

content-area teachers carry very

large rolls (e.g., 130-150 students).

There is a point when providing

truly differentiated instruction

becomes too unwieldy to be

effective. Providing differentiated

instruction is a great goal to strive

toward, but there is a limit to what

teachers can do in an effective

manner when time, energy, and

opportunity are all finite resources.

************************

Momentary Collaborative Planning of skill instruction will most likely focus on topics such as:

Identifying ways to provide opportunities for additional error-free skill practice to those students who require it.

Identifying appropriate developmental levels of individual students so that instruction is appropriately differentiated.

Linking IEP goals and identified services (e.g., accommodations) of specific students to instructional plans.

Increasing use of the teaching fundamentals, especially use of advance organizers, pre-assessing students’ skill levels,

providing scaffolded assistance, and providing explicit feedback.

Developing assessment skills for determining appropriate instructional levels.

Using appropriate progress monitoring procedures.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

9

Sustained Collaborative Planning of skill instruction will most likely focus on topics, in addition to those noted above, such as:

Identifying appropriate developmental levels of individual students so that instruction is appropriately differentiated.

Temporary Co-Teaching of skills will likely focus on modeling and coaching fundamentals of teaching skills and procedures for

differentiating skill instruction.

Sustained Co-Teaching of skills will most likely focus on simultaneous delivery of differentiated skill instruction to students whose

learning abilities vary widely.

COLLABORATION in the context of teaching Enabling Strategies

Enabling strategies are specific effective and efficient learning/social/motivation strategies necessary for success in general

education classes. Students independently use them, not because they have an assignment to use the strategies per se, but rather

because they know if they use an effective and efficient strategy, they will perform better on traditional tasks such as homework,

preparing for tests, etc. An example of a learning enabling strategy is text-perusal (e.g., the process of checking out what a text

chapter is about by paraphrasing headings and subheading, analyzing visual aids, reading the ext introduction and summary). An

example of an enabling social strategy is self-advocacy, or expressing to others a specific need and requesting their cooperation or

assistance in order for the need to be met (.e.g., a student with a reading disability requests an un-timed test). An example is an

enabling motivation strategy is setting goals, monitoring whether the goals are being attained and monitoring how well the

strategies being employed to attain the goal are working).

Typical-achieving students usually invent their own enabling strategies well enough to be successful in general education classes.

Most struggling learners, however do not. A significant body of research shows that one of the most powerful things teachers can do

to increase academic and social success of struggling learners is to teach them to use specific enabling strategies. Unfortunately,

extensive research also shows that for enabling strategy instruction to be effective, sustained, intensive and extensive instruction in

the specific strategies must be provided. The intensity of instruction required for enabling strategy instruction to be effective is NOT

conducive to providing it in traditional GE core academic classes. Alternative classes, such as a “Strategies Lab” are needed. While

integrating the enabling strategy instruction with the core academic class instruction is an effective way to support acquisition and

generalization of the strategies, integrating strategy instruction alone is usually insufficient.

If students are being provided intensive enabling strategy instruction in non-core academic class settings conducive to this kind of

teaching, then collaboration should focus on:

Edwin Ellis

(i)

(ii)

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

10

Ensuring alignment between the strategies targeted for intensive instruction and the actual setting demands of GE

content-area classes; GE and SE teachers should collaborate to determine the most salient setting demands students

face and the pertinent enabling strategies to teach. The goal is to match to-be-taught enabling strategies with authentic

GE classroom setting demands’

Once the enabling strategies have been taught an alternative setting, supporting generalization of the enabling strategy

in GE classes by targeting tactics such as:

Integrating the strategy instruction into the student’s general education classes;

Providing overt cues for students to use the enabling strategies in other settings;

Supporting student goal-setting to generalize the enabling strategies;

Reinforcing students’ attempts to apply the enabling strategies in other settings;

Providing students with explicit feedback about how well they are generalizing the enabling strategies.

Momentary Collaborative Planning of enabling strategies instruction will most likely focus on:

Identifying the critical setting demands of a GE classroom necessary for student success and determining the degree to which

individual struggling learners are meeting the specific demands.

Determining which of the demands students are not successfully meeting and then prioritizing them to determine which are

the most critical and should be targeted with enabling strategy instruction.

Sustained Collaborative Planning of enabling strategies instruction will most likely focus on topics, in addition to those noted

above, such as:

Identifying the specific enabling strategies (currently being taught struggling students in alternative classes) that are conducive

to also teaching in an integrated manner during GE classroom content-area lessons;

Determining specific ways to integrate the strategy instruction;

Determining way the GE teacher can provide students to cues to use the enabling strategies;

Determining ways to monitor student progress using the enabling strategies in the GE classroom;

Determining ways the GE teacher can provide the targeted students with encouragement and feedback regarding how well

they are applying the enabling strategies in the GE classroom.

Temporary Co-Teaching of enabling strategies will likely focus on:

Modeling and coaching use of integrated strategy instruction in the GE classroom.

Modeling how to monitor student progress in use of the enabling strategy

Modeling how to provide students with cue to use the strategies and how to provide explicit feedback and reinforcement for

their use.

Sustained Co-Teaching of enabling strategies will most likely focus on simultaneous delivery of integrated strategy

instruction with on-going content instruction.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

11

COLLABORATION in the context of teaching Subject-matter Concepts & Facts

Two of the first things that often come to mind when thinking about how to increase the success of struggling learners in coreacademic content-area classes (e.g., science, social studies) are to: (i) simplify the curriculum (make it less complex, focus on factual

information, avoid abstract concepts, etc.) and (ii) reduce the amount students are expected to learn. Both reduce students’

opportunities to learn before learning can take place and both compromise the integrity of the curriculum and both play havoc when

it comes to assigning “fair” and meaningful grades. Fortunately, there are a number of powerful tactics and strategies teachers can

use to support student learning grade-level content before resorting to these measures.

Just as skill learning is enhanced with sufficient correct practice, concept learning is greatly enhanced by the degree to which

students elaborate about the concept they are learning. Greater degrees of elaboration translate into greater degrees of relational

understanding, and precise elaborations are the most powerful. Thus, teachers collaborating on instruction in content areas should

focus, in part on:

Differentiating content (or compacting the curriculum) so

the instruction focuses on understanding core concepts

and/or big ideas rather than on memorizing a plethora of

trivia;

Identifying requisite knowledge, especially vocabulary;

determining venues that allow intensive pre-teaching (and

re-teaching) of requisite knowledge;

Ensuring elements of essential content-pedagogy are being

employed;

Determining ways to enhance the content to make it more

learnable and memorable; co-constructing enhancements;

Determining ways to make content more accessible via

circumventing students’ ability deficits (accommodations)

Designing assessment procedures that allow both preassessment of students’ background knowledge and postassessments should focus on determining the degree of

relational understanding of concepts rather than on

dichotomous (right/wrong) knowledge of facts.

Use of content enhancement tools provides a powerful

alternative to dumbing-down the curriculum. The dilemma

is that the process of selecting the appropriate

enhancements and planning instruction around them often

requires that (i) teachers have a clear understanding of

what it is students need to understand about a topic, (ii)

teachers are knowledgeable about the various enhancement

tools that would be appropriate to employ for a particular

topic, and that they are skillful in applying the

enhancement. Moreover, planning lessons that use these

enhancements sometimes requires more time and energy

than the average teacher is willing to, or able to expend.

However, planning and implementing content enhancement

tools is considerably easier when working with another

teacher. Thus collaborative planning can greatly increase

the likelihood that these tools will be used to support

student learning.

************************

A key role of the SE teacher is to assist the Content teacher in determining a given student’s level of prerequisite content knowledge

and skills, and whether accommodations and/or modifications are needed. Some students may require pre-instruction in essential

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

12

prerequisite vocabulary and related concepts needed to understand a grade-level concept that will be taught in an upcoming content

lesson. For other students at risk, background knowledge may be insufficient to learn grade level concepts, even with preinstruction; these students are good candidates for curriculum modifications (instruction in concepts leading to grade level

standards).

Momentary Collaborative Planning of content-subject matter instruction will most likely focus on topics such as:

Identifying prerequisite vocabulary and ways to review or pre-teach it;

Identifying appropriate accommodations some students may require, given the nature of the forth-coming lesson.

Linking IEP goals and identified services (e.g., accommodations) of specific students to instructional plans.

Focusing on implementing the essentials of content-pedagogy (activate prior knowledge, focus in critical features of the

concept, use of examples and non-examples, concept

Differentiating content subject matter into critical concepts

abstract concept to student’s background knowledge,

and essential understandings is a considerably easier task

reflective reviews, etc.).

when two or more teachers work together on it. Engaging

in this kind of work can, in turn, result in considerably

Sustained Collaborative Planning of content-subject matter

improved teaching behaviors in the classroom as well.

instruction will most likely focus on topics, in addition to those

Likewise, teachers working together can often develop ways

noted above, such as:

to enhance the subject matter to make it more accessible

Differentiating content objectives to identify essential

and memorable for students. They tend to design and

understandings of core concepts of big ideas;

employ more meaningful and authentic learning

Creating content enhancements (graphic organizers,

experiences, and they tend to design better assessment

mnemonic devices, etc.) and planning ways to use them

tools.

during instruction;

Creating sets of “essential questions” to pose during class and

designing ways to pose them in a manner that maximizes all students’ elaboration of the information.

Planning ways to employ peer-assisted learning tactics;

Designing meaningful assignments and ways to support students successfully completing them;

Designing meaningful activities specifically designed to enhance student understanding of the targeted core idea(s) and

motivation to learn more about the topic rather than to just entertain students during class-time.

Designing ways to enhance commonly employed tactics (how a video during class) so that they maximize opportunities for

student elaboration (employ “mediated note-taking” throughout video).

Designing assessment devices that focus on evaluating students’ breadth and depth of relational knowledge about the targeted

core concepts rather on those that focus on assessment of students’ knowledge of trivia.

Edwin Ellis

esellis@bamaed.ua.edu (205) 394-5512

© 2008 All Rights Reserved Permission is granted to copy and disseminate this document to public school teachers in the State of Alabama

Differentiating between struggling learners who could, given enhanced

content instruction (see list above), have good potential to learn gradelevel matter from those students whom the grade-level curriculum is

not developmentally appropriate; for these students, identifying

developmentally appropriate learning standards to address which lead

to attainment of grade-level standards (these will likely differ from

student to student); designing effective ways to teach these standards

in the GE classroom.

************************

Temporary Co-Teaching of content subject matter (e.g., social studies /

science) will likely focus on modeling and coaching the implementation of the

various instructional tactics and strategies developed during the sustained

collaborative planning sessions.

************************

Sustained Co-Teaching of content subject matter will most likely focus on

simultaneous delivery of differentiated content instruction to students whose

learning abilities vary widely.

************************

13

Ability grouping during skill instruction is often

appropriate because acquisition a series of skills is

a linear process highly dependent on mastery of

prerequisite skill development. Unlike learning

skills, the acquisition content knowledge is not

linear, but rather is relational. The more students

elaborate on the topic they are learning, the

greater the depth and breadth of their relational

understanding. One of the simplest ways to

facilitate student elaboration is to have them orally

discuss topics with each other. This allows students

to experience their peers’ different understandings,

perceptions, connections, etc. In other words, a

significant body of research demonstrates that

when teaching abstract concepts, students

tend to learn best when instruction is targeted at

mixed-ability groups. Thus, ability grouping during

content instruction often produces negative affects.