Freud`s last Laugh, p. 1 Guy Le Gaufey Freud`s last laugh Do you

advertisement

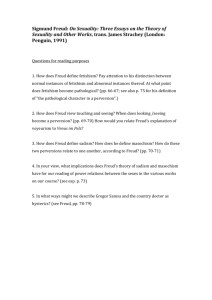

GUY LE GAUFEY FREUD’S LAST LAUGH Do you recall the way Freud describes the “fact” [die Tat] of transference in his Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis he wrote during the first World War? Because of the war, he had fewer patients during the day and fewer people to write letters to at night, so he embarked on writing a long and minutely detailed description of his discovery and his practice. Instead of the three people who had listened to his lectures about the interpretation of dreams fifteen years before, he found himself in front of an audience of more than one hundred. According to Jones, he then decided to write them cautiously, but without giving up his talents for oration. And so, twenty-six times, he starts with a “Ladies and gentlemen…”, explaining dreams, hysterical symptoms, what had not yet been called “Freud slips”, deferred action and all the usual stuff, before attacking the question of transference, which he only broaches in the twenty seventh lecture. If you remember that these lectures number twenty-eight, you begin to realize that transference has to be understood as something that arrives late at night, like Hegel’s Minerva owl. But aren’t we used to thinking that transference is on the contrary at the very beginning of a treatment and its mainspring? Why not make transference lecture number one? Why isn’t a lecture on transference the introduction to the Introductory lectures? Because transference is conceived as arriving like a surprise, and a bad one, even totally unexpected as we are told from the first paragraph of this twenty seventh lecture. Freud, once again, keeps on creating a stir: Since we are now drawing towards the end of our discussions, there is a particular expectation which will be in your minds and which should not be disappointed. […]The subject, moreover, is one that I cannot withhold from you since what you learn in connection with it will enable you to make the acquaintance of a new fact in whose absence your understanding of the illnesses investigated by us will remain most markedly incomplete1. 1 Sigmund Freud, "Transference", Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis, Complete works, p. 2713. The very first mention of the word had come earlier, in the XIXe Lecture, as such: "Instead of remembering, he [the patient] repeats attitudes and emotional impulses from his early life which can be used as a resistance against the doctor and the treatment by means of what is known as ‘transference’." No more comment then, and the twenty six other mentions (mentionings) of the word before the XXVIIIe lecture occured only through the expression "transference neurosis", without any larger explanation. "Transference" is being ignored during (throughout?) the main part of the book. Freud's last Laugh, p. 2 Let’s notice that the word transference itself keeps being unuttered, and it will stay so, even after Freud, courageously (but five pages after this quotation) has thrown a provocative “And now for the fact!” -- this unnamed “fact”, the one that he was speaking about from the beginning and that he only now begins to describe attentively without even naming it. We then read that in certain cases, the analyst can intervene correctly concerning dreams, repression, interpretation, and so on, and… it does not work! What’s happening? "After a while we cannot help noticing that these patients behave in a quite peculiar manner to us". But what “peculiar manner”? Another question then arises: Can it be that we have left the most important item out of our account? And indeed, the greater our experience the less we are able to resist making this humiliating correction for the scientific character of our knowledge [eine beschamenden Korrectur fur unsere Wissenchaftlichkeit]. And then, at last, in the next paragraph, comes the word: "This new fact, which we thus recognize so unwillingly, is known by us as transference". Whew! End of the suspense. I would like to stress here that, as strongly warned as we could be nowadays of the existence of transference in any psychoanalytical relationship, in every case, when it manifests itself, it more or less repeats for the analyst this feeling of surprise [and let me say that if it is no longer so for you, that could mean you are close to emotional death; have some rest, exercise, take a walk around the block.] But what is linked to this unexpected impression? Unfortunately, we are used to considering that transference and love are almost equivalent. In one of his recent books, L’Amour Lacan, Jean Allouch created the neologism “transmour” to point up this quasi similarity. Even so, the first uses of the word “Uberträgung” in Freud were quite different insofar they clearly meant a sort of error in the link between two ideas. Let me recall one of the instance Freud gave, in The Interpretation of Dreams (for the second time, then), of what is a “false connection” (“falsche Verknüpfung”) that deserves to be considered as a “transference”: On one occasion during a sitting of the French Chamber a bomb thrown by an anarchist exploded in the Chamber itself and Dupuy subdued the consequent panic with the courageous words: ‘La séance continue.’ The visitors in the gallery were asked to give their impressions as witnesses of the outrage. Among them were two men from the provinces. One of these said that it was true that he had heard a detonation at the close of one of the speeches but had assumed that it was a parliamentary usage to fire a shot each time a speaker sat down. The second one, who had probably already heard several speeches, had come to the same conclusion, except that he supposed that a shot was only fired as a tribute to a particularly successful speech. These provincials did have a reason to make such assumptions. This event occurred indeed less than fifteen years later after a bill was passed, in 1880, ordering that the 14 th of July will be from then on the national day, and that there will be gun or cannon shots in every city and village to celebrate in common the unity of the country at noon. So, authorized as they were that day to be present in the holy of holies of the Republic, it was not so foolish for them to consider this explosion as an outburst of glorious republicanism. But they were wrong, definitely wrong and, like Freud, we are prone to laugh at them, coming from the "provinces", which means, in a centralized country as France, something close to the disdainful "peasant". Freud's last Laugh, p. 3 When Freud decided to use the word « Übertragung » to mean also the relationship established from the patient to the analyst (and then only in a singular form, whereas the first meaning came often in plural), he already had this idea of a « falsche Verknüpfung », « false (or fake, if not forged) connection ». In the section in Studies on Hysteria “The Psychotherapy of Hysteria”, he clearly stated that “transference on to the physician takes place through a false connection 2”. With such a definition in his mind, he could resist to the demand of love coming out in the treatment from childhood and for neurotic reasons, and as a considerable weapon of resistance. But later on, when he commented on transference itself in his “Observations about transference-love”, he eventually comes to write : “We have no right to dispute that the state of being in love which makes its appearance in the course of analytic treatment has the character of a ‘genuine’ love." This apparent contradiction between a "false connection" which is at the same time a "genuine love" has caused a lot of ink to flow. But it is also the point where I find my way towards laughter. According to the same Freud, surprise is indeed a key component in any bursting of laughter. I of course do not mean that someone falling in transference-love is laughable, even if any love can make a fool of anyone. No, my actual point is: how a "humiliating correction" as transference could be such a surprise that the analyst him/herself would be caught in something somehow ridiculous, funny, and maybe silly, at least something very different from the usual seriousness of rationality ? This last word gives us a clue: rationally speaking, if you are in front of something which is at the same time « false » and « genuine », you have got a problem and you know that you have to chose, one side will have to go. But contrary to this rational necessity, and in spite of the fact he was filled with concern about his « Wissenschaftlichkeit », Freud holds on tight and decides to keep both sides. Of course, he also knows as a result that his ambition of « scientificity » is going to suffer from such a contradiction put so decidedly. I personally add that if Lacan could say, in his more provocative manner, that the analysis is a swindle, “une escroquerie”, this occurred precisely at the same place and for the same reasons, in keeping with transference. Let me be clear about this place: the point is not to consider that something false leads to something true or genuine. This would be no surprise at all, and would correspond to the logical operator « implication ». This operator knows only one impossibility : that “wrong” comes from “true”. But from “wrong” itself come as well “wrong” as “true”. Both are perfectly correct. So that the logical and rational difficulty Freud encounters with transference is that it is at the same time and on the same level, true and false, false and true. (Mœbius strip-tease?...) It would be a bit of fun scanning the Freudian landscape of the last century to see that, if a few people fell on the only side of « genuine love » (sometimes to the point they married their patients), a lot of people opted, openly or secretly, for the theory of transference as a pure and simple « false connection ». That was the religion of American ego psychology, but in France somebody like Maurice Bouvet could consider the analyst as a surface receiving pathological and neurotic projections, the 2 S. Freud, Standard Edition, p. 224I of Freud's last Laugh, p. 4 work of the analyst being then to confront these “misconceptions” to the supposed “reality” of the analyst him/herself, as a sort of first step to the reality of the world itself, supposed not to be neurotic. The advocates of the “wrong” side and the advocates of the “genuine” side are always deadly serious, up to the point they profoundly despise the ones to the others. You are not supposed to laugh when each one tries to explain to you what transference is, in fact, truly, actually, in its core, and so on… But if, to the contrary, someone confess to you that he or she is not able to differentiate between false and true, between “wrong” and “genuine” when it comes to transference, that he or she is split as well as splitting, he or she risks being in a laughable position. The one who is in charge of looking for truth would recognize being unable to bring to a close such crucial a point? Wouldn’t it be a case of the biter bit? An ultimate defense against this messy point would be to consider transference as just a trick, like hypnosis, a sort of catalyst that comes naturally and that the analyst endures as something partly useful partly embarrassing, a pain in the arsenal of analytical technique. I do prefer to present it to you as a fact “unwillingly accepted”, as Freud wrote it down, but I want to elaborate a little further upon the situation created by such a stance. It looks like the analyst would be cheated. S/he could say: “I had proposed you a game – speaking your mind –, you said yes, you agreed, and now you want to play another game with me. It is not fair!” But if, according to the fundamental rule, anything can be told inside the session, there is no reason not to speak about feelings of any kind, including love, hatred, contempt, jealousy and the like. So that the analyst is cornered precisely in the trap s/he set at the very beginning; s/he cannot ignore it, and therefore cannot disregard it. The comic side of this situation is sometimes put on stage, thanks to Freud once again, with Breuer’s story in front of Anna O’s declaration of love, his sudden trip in Italy with his wife, and the baby that was the natural and legitimate outcome of all this shadowy affair that made Freud – and the legion of Freud’s readers – smile, if not laugh. Is the analyst in a better position today? I won’t go that far, insofar as Lacan made it worse with his consideration according to which the analyst comes to be, in the sheer movement of transference, this object (a) that hardly deserves its name of “object” since it lacks unity, specularity, and even existence in the usual meaning of this word. The subject supposed to know is, at the same time and on the same level, this blind “object”, and BOTH are transference. This waltz between object and subject can be better appreciated through this witty remark from Lacan. One day, a woman attending his seminar complained about the fact that he was all the time speaking of the loved person as “the object of love”; to which he replied: “Oh my dear, if only you knew what I think of the subject!” Now, it is time for us to remember that, at the conclusion of his large work about “Der Witz”, in the last paragraph of his chapter “Jokes and the Species of the Comic”, Freud condenses the differences he carefully established all along his book about jokes, comic and humor thanks to one simple formula. The pleasure due to the first one, the joke, results from “an economy of expenditure upon inhibition” [Hemmungsaufwand]; for the third one, humor, pleasure comes from “an economy of expenditure upon feeling” [Gefühlsaufwand], but for the one which is paramount to us now, the Freud's last Laugh, p. 5 pleasure of the comic that causes laughter, it ensues from “an economy of expenditure upon ideation (upon cathexis)” [aus erspartem Vorstellungs(Bezetsungs)aufwand]. This economic consideration partly rescues us from the logical contradiction into which we felt trapped. The “false connection” of our “provincials” was indeed an economy, we even should say “a saving”, upon the work of thought insofar as an anarchist bombing in the Chamber called for a deep and actual and difficult understanding of the French society at the end of this century. But equally, in order not to run off to Italy and have a baby, Breuer would have been in need of a large part of psychoanalytical knowledge, which was not available for anyone at that time. So that the comic of transference does come under haste, not only on the side of the analysand, hurried to locate a spring of meaning no matter what, but also on the side of the analyst who agrees on the spot to what is addressed to him or her (love, hatred, disdain, indifference, curiosity, and so on) without knowing so fast why nor how to do with that. The comfortable (and truthful) assertion according to which this is a repetition of an infantile position, an “acting-out” [eine Agieren] instead of a remembrance, keeps being but half a truth: we also must eventually consider it as something “genuine”, actual and true, even on the side of the analyst. Once, Lacan insisted on this, telling that while analysts know for a long time that they can be considered as shit, the only point they keep on ignoring is how much it is not a metaphor. The comic power of transference relies on the “fact” of this mixing, this blending, this concoction between true and false, true as false and false as true. There is nothing like a truth to lie to oneself; there is nothing like a lie to be disclosed, and that is a matter of laughter. Sometimes.