The Genetics of Aging - People at Creighton University

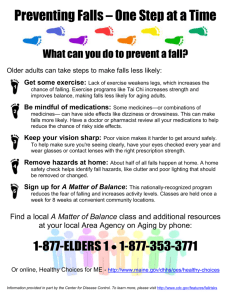

advertisement

Genetic Mechanisms Running head: GENETIC MECHANISMS OF AGING Genetic Mechanisms Involved in the Aging Process Erica F. Reinig Creighton University 1 Genetic Mechanisms 2 Genetic Mechanisms Involved in the Aging Process Throughout time, society has been obsessed with the concept of immortality. The Spanish explorer Ponce de León is famous for his exploration of the New World in search of the fountain of youth. Even today, people are intrigued by the idea of immortality. J.K. Rowling’s increasingly-popular book Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone tells the story of how a young wizard must keep an evil Lord Voldemort from gaining possession of the Sorcerer’s Stone, an unusual object that can produce an elixir that allows the drinker to live forever. Although explorers never found the fountain of youth and the Sorcerer’s Stone exists only in imagination, humanity has held onto its feverish pursuit of immortality. People long to become a modern-day Methuselah, rebel against death, and avoid separation from loved ones. Despite their high hopes, many people have declared immortality to be a physical impossibility. However, recent advances in the field of biology and genetics have yielded interesting insights into the causes of aging. This new information on the role of telomeres, telomerase, oxidative stress, and many other influences in the processes of aging causes scientists to question whether or not immortality might one day be possible. The secrets of cellular aging begin in the cycle of cellular mitosis. During mitosis, the DNA of the cell duplicates and the cell divides. Continual replication results in damage to the DNA strands of cells. Molecular structures called telomeres work to protect DNA strands from damage. Complete telomere loss leads to an instability within genetic information, causing the cell to die (Von Zglinicki, 1998). Telomeres consist of several repeat sequences that reduce the rate of DNA erosion. This sequence, 5’‘(TTAGG)n-3’ in humans, repeats itself an average of 2,300 times in germ line cells Genetic Mechanisms 3 (Von Zglinicki). Telomeres also have a very high degree of length polymorphism. However, cellular division erodes telemetric DNA, causing telomeres to become shorter, with 5-30 telometric repeats lost per division (Von Zglinicki). If telomeres become too short, cells are no longer able to divide. This point in the cellular cycle in which cells are unable to undergo mitosis is known as the Hayflick limit (Von Zglinicki). If telomere shortening does not occur, through telomere lengthening or maintenance, then cellular aging does not occur. An area of great diversity, the length of telomeres is extremely important in determining the rate of the aging process. Humans also display a great deal of variance in length of telomeres. Statistics suggest that sex, age, and smoking may be influential in telomere length and rate of deterioration (Nawrot, Saessen, Gardner, & Abraham, 2004). Perhaps the most notable difference exists between men and women. The women’s telomeres shorten at a rate of 0·019 kb per year while men’s telomeres shorten at a rate of 0·024 kb per year (Nawrot et al.). While the exact cause of these differences is not certain, researchers believe that they may know the time that these differences begin to arise. Because telomere length in white blood cells is very similar in newborn girls and boys, this sexual dimorphism may not begin to appear until after individuals are born (Nawrot et al.). One possible cause of telomere differences between sexes relates to reactive oxygen. Females produce lower levels of reactive oxygen, a substance that increases telomere erosion, and metabolize these levels more quickly than men (Nawrot et al.). Reactive oxygen may also account for shorter telomere length in smokers. The levels of reactive oxygen are often much higher in smokers than in non-smokers (Nawrot et al.). Other substances and situations may also lead to an increased rate of telomere erosion. A recent study suggests that Genetic Mechanisms 4 telomere erosion may increase in the presence of UVA irradiation, a type of ultraviolet radiation which penetrates deep into the dermal layers of the skin (Oikawa, Tada-Oikawa, & Kawanishi, 2001). Some scientists now believe that telomere length may be an X-linked trait (Nawrot et al., 2004). Researchers recently studied white blood cell DNA in families in order to compare telomerase length in hopes of finding a genetic correlation for the aging process (Nawrot et al.). After experimenting and gathering and comparing data, researchers came across an extraordinary correlation. There were high levels of similarity of telomere length between fathers and daughters, mothers and sons, and mothers and daughters, leading researchers to believe that telomere length may likely be an X-linked trait (Nawrot et al.). Researchers then began to look for specific genetic loci on the X chromosome that would support their conclusion. Several specific connections between telomere length, longevity, and the X chromosome support this X chromosome hypothesis. The DKC1 gene, which encodes for dyskerin, can be found on the X chromosome and plays a key role in the accumulation of a certain component of telomerase, which works to lengthen telomeres (Nawrot et al.). The gene called AGTR2, also located on the X chromosome, when stimulated increases production of nitric oxide, which may help reduce oxidative stress on cells (Nawrot et al.). The MGST-I enzyme, which protects the cell from oxidative stress, may also be connected to the X chromosome. The enzyme Mgstl in Drosophlia may be related to a gene on the X chromosome and is very similar to the MGST-I enzyme in mammals (Toba & Aigaki, 2000). The similarity of the enzymes suggests that they may possibly have roots in the same location, the X chromosome. Another telomerase connection to Genetic Mechanisms 5 the X chromosome lies in the hormone estrogen, which can stimulate hTERT, one component of telomerase (Nawrot et al.). The correlation of telomere lengths between mothers and offspring can be explained using mitochondria. Along with working to control oxidative stress damage, mitochondria also have a maternal connection because they usually originate from the mother (Nawrot et al.). While several pieces of evidence support the X chromosome hypothesis, further research is needed before scientists can become more certain about the relevance of the X chromosome to aging and telomere length. While telomeres work well to delay and prevent the damages that cause aging, there is another molecular component used by several cells that gives the cell a form of immortality. Another mechanism that works to prevent aging within a cell is ribonucleoprotein reverse transcriptase, also called telomerase. This substance works to elongate telomeres and prevent their shortening by using internal RNA (Von Zglinicki, 1998). Telomerase has two active components. The first component, hTER, is a RNA template for polymerase activity; the second component, hTERT, is a catalytic subunit that has reverse transcriptase activity (Poole, Andrews, & Tollefsbol, 2001). In order for a cell to have telomerase activity, two components of telomerase must be present. While the hTER component is commonly found in human somatic and embryonic tissue, hTERT is usually not present in these types of tissue (Poole et al.). As a result, human somatic cells usually do not have telomerase activity; however, there are several types of cells that do display this type of aging prevention. Telomerase activity is very common in germ line cells, unicellular organisms, some forms of somatic tissue (trophoblasts, hematopoietic cells, and endometrial cells), Genetic Mechanisms 6 and up to 95% of cancer cells tested (Poole et al., 2001; Von Zglinicki, 1998). As a result of their telomerase activity, these cells do not experience the telomere shortening experienced by typical somatic cells. While telomeres are effective in reducing the effects of continual cellular division, telomerase activity is necessary to produce an immortal phenotype within a cell (Von Zglinicki). Recent research focused on how to possibly control the effects of telomerase within a cell. According to this research, telomerase activity can be greatly decreased by the use of 13-ribosome, which targets the mRNA of hTERT (Poole et al). The ability to decrease telomerase rate (and increase the aging process) may prove as useful as the ability to decrease signs of aging. Telomerase research could have great implications on the field of oncology and other age-related diseases. For this reason, many researchers are eager to learn more about the combined effects of telomerase and telomeres on the prevention and acceleration of cellular aging. However, additional research into the area of aging and genetics has produced several other mechanisms behind cellular aging. One major cause of telomere shortening within the cell is oxidative stress. Denham Harman developed the first likely mechanism for cellular aging involving oxidative stress: “[C]ontinuous generation of deleterious oxygen free radicals as a byproduct of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism would eventually lead to intolerable damage and thereby determine cellular life span” (Von Zglinicki, 1998, p. 318). This theory has become one of the most influential theories in the study of molecular aging today. Numerous studies have shown that oxidative stress creates damage within telemetric DNA. Acting as oxidative stress sensors, telomeres may halt the cells cycle under conditions of mild and chronic damage due to oxidative stress (Von Zglinicki). In Genetic Mechanisms 7 this way, telomere functioning may act as an indicator of levels of oxidative stress. Researchers have recently observed that telemetric erosion can be increased in vitro by use of chronic oxidative stress; in fact, cells undergoing hyperoxia had telomeres of a similar length to those cells that had reached the Hayflick limit (Von Zglinicki). Other studies have arrived at similar conclusions involving the increased erosion of telometric DNA due to oxidative stress (Highfield, 2002; Toba & Aigaki, 2000). One experiment into the effects of oxidative stress on the aging process involved the use of fruit flies. By mutating a certain gene (called the “Methuselah gene” by Seymour Benzer), researchers enabled fruit flies to resist the stresses of radical-forming herbicides which cause oxidative stress; the life span of those mutated fruit flies increased by 35% (Highfield, 2002). Other genes may also play a role in coping with oxidative stress. Research suggests that the previously mentioned enzyme MGST-I helps protect the cell from oxidative damage (Toba & Aigaki, 2000). Similar studies continued the use of fruit flies in research into the role of antioxidants in oxidative stress. Genetically engineered to produce higher levels of antioxidants (which protect against free radicals and oxidative stress), fruit flies increased their life expectancy from the typical 45 days to 75-95 days (Highfield). While scientists have been able to manipulate oxidative stress levels in fruit flies fairly well, additional studies have managed to do the same for mammals. By deleting a gene called p66shc, researchers created mutant mice that lived one-third longer than normal, non-mutant mice (Highfield). Science has shown that oxidative stress plays a key role in the deterioration of telometric DNA, drastically influencing the rate of damage which causes aging. Along with the implication of Genetic Mechanisms 8 oxidative stress, the possibility arises for another link to molecular aging: mitochondria, which may be responsible for several links to molecular aging. Numerous studies have arrived at the conclusion that mitochondria play an integral role in regulating cellular damage and aging. Compounds like ROS, which can be found in mitochondria, are capable of destroying nucleic acids, lipids, proteins, and many other forms of biomolecules (Osiewacz, 2002). The damage created by ROS may in part be responsible for cellular aging. A recent study discovered that ROS levels are lower in the mitochondria of younger organisms (Osiewacz). ROS proves to be a very damaging threat to the well-being of the cell. As this study has shown, increased damage of the mitochondrial respiratory system (often caused by ROS) leads to an increase in ROS production, which in turn leads to increased damage (Oseiwacz). ROS production, as a result, continues a self-perpetuating cycle of damage that eventually leads to mitochondria that are incapable of functioning. Mitochondria also contain several substances that can increase the lifespan of the cell. Scientists have discovered that longevity of the cell increases in the presence of mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibitors (e.g. mucidin and potassium cyanide) as well as the substances ethidium bromide, acridine, and acriflavine (Oseiwacz). Additional observation involving substances within mitochondria yielded yet other possibilities for mechanisms of longevity. Kanamycin, neomycin, streptomycin, puromycin, and tiamulin all serve as inhibitors of mitochondrial ribosomes and may be effective in extending lifespan (Oseiwacz). While research involving mitochondria and oxidative stress has already suggested several possible mechanisms for cellular aging, there is yet another theory of molecular aging that provides additional possibilities for longevity. Genetic Mechanisms 9 The caloric restriction theory of aging is another major theory of cellular longevity that has been the focus of several research studies. The basic outline of the theory is that lowering calorie intake can increase cellular longevity. If individuals cut their calorie intake by 30%, research suggests that they can increase their lifespan by an average of 20 years (Highfield, 2002). Scientists at MIT have also found a more specific connection between calorie restriction and longevity (MIT, 2004). According to MIT researchers, calorie restriction prolongs lifespan by activating the SIR2 gene which results in the production of a protein called Sir2 (MIT). While Sir2 is normally restricted by coenzyme NADH, low calorie diets restrict production of NADH, allowing another coenzyme, NAD, to activate the Sir2 protein (MIT). Some genes regulating food metabolism may also play a large role in calorie restriction and increased longevity. A daf-2 mutation in a nematode worm influenced the worm’s lifespan in a study by Michael Klass at the University of Colorado (Highfield). Evidence of caloric restriction’s impact on the longevity of cells is abundant. With multiple mechanisms behind telomere length and lifespan, including telomerase, oxidative stress, mitochondria, and calorie restriction, researchers have now begun to investigate the possible applications of the new information regarding DNA and aging. Once scientists discover more information about the underlying mechanisms of the cellular aging process, they will be more capable of using information on the genetics of aging to assist the medical field. One of the largest concerns about research into the mechanisms of biological aging is age-related diseases, such as cancer. Scientists have suggested that shorter telomeres may cause a greater predisposition to age-related disease (Nawrot et al., 2004). The shorter telomere phenotype is not only more likely to get an age-related disease but Genetic Mechanisms 10 also more likely to die from an infectious disease. Individuals at the bottom of the 25% distribution for telomere length had a mortality rate from infections diseases eight times higher than individuals at the top 75% of the distribution curve (Nawrot et al.). Studies regarding cancer and aging often include telomerase because of the evidence of its involvement in cancerous cells and substances. The expression of hTERT is increased when in the presence of the oncogene c-Myc (Poole et al., 2001). However, oncogenic proteins are not the only substances involved in the expression of hTERT. The antioncogenic proteins p53 and WT1 also have an effect of hTERT, inhibiting its expression (Poole et al.). Another substance related to the tumor suppressor p53, p21, may also play a role in cell division and aging. In non-dividing cells, p53 is activated, blocking cell division, and levels of p21 increase (Von Zglinicki, 1998). Additional research into the relationship between aging and cancer would be of great benefit to cancer patients and that doctors who treat them. While exact connection between hTERT and cancer is still uncertain, there are several practical applications for the field of oncology. Upon observing that excessive cancer preventing protein in mice increases their rate of aging, researchers proposed the theory that the body creates state of equilibrium between resisting the process of aging and increasing risk for cancer (Highfield, 2002). If this theory holds true, understanding this equilibrium will profoundly benefit the field of oncology. Additional applications in cancer treatment focus specifically on diagnosis. As hTERT is detectable even during the earliest stages of malignancy in tumors, oncologists could possibly use hTERT levels when diagnosing cancer (Poole et al., 2001). Needless to say, further information regarding telomerase and its underlying mechanisms would greatly benefit many areas of Genetic Mechanisms 11 cancer research. In addition to oncology, information on the genetics of aging also has several other practical applications. In the genetic disorder Werner’s syndrome, sufferers undergo significant aging during adolescence. According to researchers, this syndrome may be the result of a faulty version of the enzyme helicase, which plays a key role in cell replication by unwinding DNA strands for duplication; an error in helicase functioning could increase the rate at which the cell ages (Highfield, 2002). Further research into helicase and DNA replication could provide information leading to treatments or possible cures of Werner’s syndrome. In addition, if researchers are able to slow down the erosion of telomeres in cells, they may be able to slow the effects of aging and decrease risks for age-related diseases (Von Zglinicki, 1998). Additional research into oxidative stress would also be beneficial. Currently, researchers are interested to see if antioxidative treatments would be able to slow the damage to telomeres due to oxidative stress (Von Zglinicki). While telomerase, especially hTERT, has several possibilities for future treatment against aging, it could also be very risky. The use of hTERT for cellular immortalization in vivo leads to a high susceptibility to neoplastic transformation (Poole et al., 2001). Although research into the genetics of aging is still in its early stages, the possibilities of this field of research are innumerable, from possible treatments for cancer to the simple idea of helping people live longer. With the pace at which genetic advancements are advancing, these medical breakthroughs may one day be possible. There are few people who would not be interested in the enormous implication of these studies: the fountain of youth may not just be a myth. It might actually exist within some of the tiniest particles of the human cell. Research into telomere length, telomerase, Genetic Mechanisms 12 oxidative stress, and many other molecular components implicated in aging has provided humanity with incredible new information that may lead to an increase in longevity; however, in remains to be seen whether “the fountain of youth” will ever be within scientific grasp. It may be possible in the future, however, to use this new information to assist the quality of life by treating cancer or just adding on a few more years to the human lifespan. Much more research is needed before any of these applications can be realized. However, with a goal as tantalizing as immortality, there is no doubt that scientists will continue to research the genetics of aging. Perhaps society will never find the legendary Sorcerer’s Stone. However, even if immortality is impossible and can never be achieved, people will still dream about it. Books will still be written about it. People will still chase it. The dream of immortality has been and always will be a large part of human culture, no matter how impossible that dream may sometimes appear. Genetic Mechanisms 13 References Highfield, R. (2002). The Science of Harry Potter. New York: Penguin Books. MIT helps unlock life-extending secrets of calorie restriction. (2004, January 30). Genomics & Genetics Weekly, 8-9. Nawrot, T. S., Saessen, J. A., Gardner, J. P, & Abraham A. (2004). Telomere length and possible link to X chromosome. The Lancet, 363, 507-510. Oikawa S., Tada-Oikawa S., & Kawanishi S. (2001). Site-specific damage at the GGG sequence by UVA involves acceleration of telomere shortening. Biochemistry, 40(15), 4763-4768. Osiewacz, H. D. (2002). Mitochondrial functions and aging. Gene, 286, 65-71. Poole, J. C., Andrews L. G., & Tollefsbol, T. O. (2001). Activity, function, and gene regulation of the catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT). Gene, 269, 1-12. Toba, G., & Aigaki, T. (2000). Disruption of the Microsomal glutathione S-transferaselike gene reduces life span of Drosophlia melanogaster. Gene, 253, 179-187. Von Zglinicki, T. (1998). Telomeres: Influencing the Rate of Aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 854, 318-327.