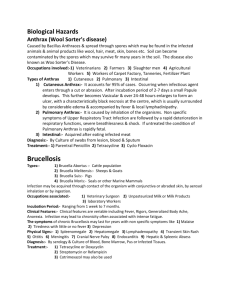

Anthrax Info - DoD

advertisement