The Anti-Bullying Research Project Report

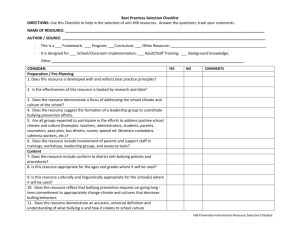

advertisement