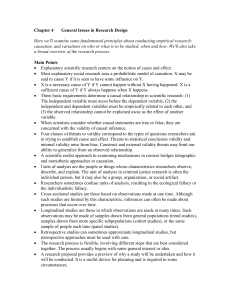

Doc Version - University of Bristol

advertisement

CARTWRIGHT’S CAUSAL PLURALISM: A CRITIQUE AND AN ALTERNATIVE Francis Longworth University of Birmingham 3280 words In Hunting Causes and Using Them Cartwright argues that causation is not a monolithic concept but instead is pluralistic. Causation is most directly represented, she claims, by a variety of ‘thick causal concepts’ (typically causative verbs) each of which is richer in content than the ‘thin’ concept ‘cause’ itself; since there is no single feature that these thick causal concepts all share, univocal analysis of causation is impossible. I suggest that Cartwright’s account is problematic in several ways. It is not clear what the extra content of causative verbs is supposed to consist of, and crucially, whether it is extra causal content. It is therefore questionable whether Cartwright has offered a genuinely pluralistic theory of causation at all. I outline an alternative pluralistic theory of causation that is not subject to these objections, according to which causation is a disjunctive concept. Unlike Cartwright’s account, this disjunctive theory of causation makes the content of causal concepts clear and explicit, and hence makes the basis of the theory’s pluralism clear and explicit. It follows from this theory that some (but not all) causal concepts are causally richer than the bare concept ‘cause’, and furthermore, that their causal content or ‘thickness’ can be quantified. This pluralistic theory has the advantage of being able to account for the continued failure of univocal analyses of causation, without having any of the drawbacks of Cartwright’s pluralistic account. 1. Cartwright On Thick Causal Concepts In part I of Hunting Causes and Using Them, Cartwright puts forward a pluralistic account of causation. Under the influence of Hume and Kant we think of causation as a single monolithic concept. But that is a mistake (p.19). [T]here are untold numbers of causal laws,1 all most directly represented using thick causal concepts2, each with its own truth makers; and there is no single interesting3 truth maker that they all share by virtue of which they are labelled ‘causal’ laws (p.22). [T]he pistons compress the air in the carburetor chamber, the sun attracts the planets, the loss of skill among longterm unemployed workers discourages firms from opening new jobs…These are genuine facts, but more concrete than those reported in claims that only use the abstract vocabulary of ‘cause’... If we overlook this, we will lose a vast amount of information that we otherwise possess, important, useful information that can help us with crucial questions of design and control. (p.19-20). All thick concepts imply ‘cause’. They also imply a number of non-causal facts. But this does not mean that ‘cause’ + the non-causal claims + (perhaps) something else implies the thick concept. For instance, we can admit that compressing implies causing + x but that does not ensure that causing + x + y implies compressing for some noncircular y. (p.22). These claims may be interpreted as follows: (i) What Cartwright terms ‘thick causal concepts’ (typically causal verbs such as ‘compress’, ‘attract’ and so forth) express additional information to that expressed by the ‘thin’, abstract concept ‘cause’; they have a richer content than ‘cause’ has. I take ‘causal laws’ to be interchangeable with ‘causal relations’ here. Italics added. 3 Note that Cartwright states only that there is no interesting truth maker that each causal concept shares. Might it be that there is an uninteresting truth maker that they all share? This possibility is consistent with there being a variety of different causal relations, with correspondingly numerous methods for design and control. Perhaps the use of the word ‘interesting’ is merely meant to exclude analyses that are of no practical help in matters of design and control. If so, there could be a successful univocal analysis of the metaphysics of causation, even if it did not satisfy Cartwright’s stated desideratum that a theory of causation should integrate metaphysics, method and use. Pluralism of this form is very weak, however. A stronger form would include metaphysical pluralism: the claim that there are no individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions whatsoever for a relation’s being causal, and hence no univocal analysis. In the remainder of this paper, I will restrict myself to discussion of this stronger claim. 1 2 1 (ii) Because this extra content is not common to all causal verbs, causation cannot be captured in a univocal, or ‘monolithic’ analysis. (iii) Instead, causation is a pluralistic notion that is best represented by thick causal concepts. The logical form of the concept is presumably: C is a cause of E iff (C compresses E) v (C attracts E) v (C discourages E) v … Each thick concept implies cause, and if C is a cause of E, it is so in virtue of a particular thick causal relation holding between C and E. Such an account is highly pluralistic; there are potentially (at least) as many causal concepts as there are causative verbs. (iv) Thick causal verbs are not composites of the bare concept ‘cause’ and this additional content; they do not jointly imply the thick causal verb. 2. Some Objections to Cartwright’s Account Cartwright’s account is puzzling in several ways. First, is not clear why ‘cause’ plus something else could not imply a particular causal verb. For example, ‘causing to change in volume via the local application of force’ would appear to imply ‘compressing’. It is not clear what the extra content of ‘compress’ could be, such that it could not be expressed as a composite of ‘cause’ and something else. Second, and more problematic, it is not clear that the extra content of ‘compress’ is actually extra causal content. Hitchcock has recently expressed doubts on this point, with regard to another of Cartwright’s examples: It is certainly true that the claim “the carburetor feeds gasoline and air to a car’s engine” conveys more than that the carburetor causes gasoline and air to be present in the engine. The word “feed” has subtle shades of meaning. In its paradigm usage, it applies to the provision of food for consumption by a human being (or other animal). The use of the word “feed” in this context thus naturally invites a simile: air and gas are to a car’s engine as food is to a human body. The air and gas are fuel for the engine, just as food is our fuel. This kind of nuance would be lost if the bare word “cause” were used instead. But now a question arises: is the extra richness infused by the use of the word “feed” instead of “cause” itself causal in nature? That is, should we really say that “feeding” is a thick causal concept that outstrips the bare notion of cause, or should we rather say that the meaning of the word “feed” outstrips its purely causal implications? It is not clear to me that the causal content of the claim [“the carburetor feeds gasoline and air to a car’s engine”] is not exhausted by the claim that the carburetor causes gasoline and air to be present in the carburetor, even if it manages to say more than this.4 The significance of Hitchcock’s worry is that if the extra content of causal concepts were not causal, this would undercut Cartwright’s argument for causal pluralism. For if the extra content were not causal, no theory of causation would need to capture that content in a definition. The extra non-causal content would merely serve to mark out different species of causation, united under a common genus that could be analyzed univocally. While the species would differ from one another, they would not differ causally. It is not clear from Cartwright’s account how one might determine whether the mysterious extra content is indeed causal or not. It is therefore unclear that Cartwright has even proposed a genuinely pluralistic theory at all. In the following section I outline an alternative pluralistic theory of causation that makes the content of causal concepts clear and explicit. In consequence, the basis of the theory’s pluralism is also clear and explicit. According to this theory, some (but not all) causal concepts are causally richer than the bare concept ‘cause’. In addition, the theory offers a metric for quantifying and comparing the causal content of various causal concepts. 3. An Alternative Pluralistic Account: The Disjunctive Theory of Causation The Disjunctive Theory of Causation (DTC) is formulated not in terms of thick causal verbs, but rather in terms of relations that may hold between causes and their effects, such as counterfactual dependence, manipulability, probability raising, physical connection/locality, transference of some physical quantity from cause to effect, asymmetry, transitivity and so on. The set comprised of all of these criteria is sufficient for a relation’s being causal. Many familiar causal relations appear to instantiate all of the criteria – billiard ball collisions, for example. Certain subsets of these criteria are also sufficient for a relation’s being causal, and these subsets are disjunctively necessary. The general logical form of (DTC) is given by ‘How to Be a Causal Pluralist’, in Thinking About Causes eds. Machamer and Wolters, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 2007. 4 2 (DTC) C is a cause of E iff ((P&Q) v (R&S) v T v …) where P, Q, R and S are criteria taken from the set above. For example, one might propose the following particular disjunctive theory: (DTC1) C is a cause of E iff (manipulability & probability raising) v (locality & transference) v (counterfactual dependence) Each disjunct is sufficient condition for causation;. In addition, each disjunct should be a minimal sufficient condition for causation; each element of each disjunct should be non-redundant. No disjunct should be redundant; that is, it should not be entailed by any other disjunct. This condition ensures that there is not set of conditions that are shared by all disjuncts, and hence that are no necessary and sufficient conditions for a relation’s being causal; that is, the theory is genuinely pluralistic. No univocal analysis can cover both disjuncts. There may, however, be considerable overlap between the disjuncts, with some criteria appearing in more than one disjunct (although this is not the case for (DTC1)). Some criteria may even be necessary (though of course not necessary and sufficient, for then that criterion could itself serve as a univocal analysis and the theory would not be pluralistic). (DTC1) represents only one possible way of filling in the content of the disjunction. The analysis of causation proposed by Ned Hall in his paper ‘Two Concepts of Causation’ can be thought of as having the simplest possible disjunctive form.5 He claims that there are two distinct concepts of causation: production and dependence, where production is an intrinsic, local relation, perhaps involving some kind of lawlike sufficiency, and dependence is straightforward Lewisian counterfactual dependence.6 Hall’s analysis can be formulated disjunctively: (HALL) C is a cause of E iff (C produces E) v (E depends on C) The disjunction could potentially be much longer, however. But it would probably still be much shorter than Cartwright’s enormously long disjunction of thick causative verbs. The task of fully specifying all of the disjuncts may be time-consuming and difficult, requiring the testing of the sufficiency and minimality of each candidate disjunct against potential counterexamples. Let us stipulate, however, for the expository purposes of the remainder this paper, that (DTC1) is correct. Regarding the causal content of a causal concept, the basic proposal of (DTC) is that the more disjuncts a concept entails, the greater is its causal content. Let us also say that a concept’s causal thickness is given by the magnitude of its causal content. More formally, (1) The causal content or causal thickness of a concept C is measured by the number of disjuncts it entails. (2) C has more causal content than ‘cause’ iff C entails one or more disjuncts in (DTC). That is, C entails (P&Q), or C entails (R&S), or C entails T, or… (3) C has the same causal content as ‘cause’ iff C entails ‘cause’ but does not entail any specific disjunct (that is, C does not entail P&Q, C does not entail R&S, C does not entail T, …). (4) C has no causal content iff C does not entail ‘cause’. We are now in a position to return to the example discussed by Hitchcock above. Hitchcock states that it is not clear to him that the causal content of the claim “the carburetor feeds gasoline and air to a car’s engine” is not exhausted by the claim that the carburetor causes gasoline and air to be present in the carburetor. (DTC1) is able to provide a principled answer to the question of whether, as Cartwright claims, the concept ‘feeds’ has more causal content than is implied by the thin concept ‘cause’. Let us suppose, as seems plausible, that ‘feeds’ entails locality and transference. That is, the feeding relation between the carburetor and the engine is local and involves transference of some physical quantity (via the gasoline and air) from the carburetor to the engine. ‘Feeds’ will have more causal content that the word ‘causes’, since ‘causes’ does not entail (locality & 5 6 Hall (2004), in Collins Hall and Paul, eds. (2004) Causation and Counterfactuals, MIT Press. Boston. Lewis (1973) ‘Causation’. 3 transference); it only entails the disjunction (manipulability & probability raising) v (locality & transference) v (counterfactual dependence). So, if (DTC1) is correct, then the causal content of the word ‘feed’ does outstrip the causal content of the bare word ‘cause’, and ‘feeds’ is therefore a causally thicker concept than ‘causes. ‘Feeds’ implies more information about the type of causation operating than ‘causes’ itself does, namely that causation involves local transference. Local transference is not merely a species of the genus causation that shares all of its causal content with the other disjuncts/species of causation, but is itself a particular genus of causation that differs causally from other genera in a way that cannot be captured in a univocal analysis. Not all causative verbs, however, have causal content that outstrips that of the concept ‘cause’. Some are as ‘thin’ as ‘cause’ itself, if, in accordance with (3) above, they do not imply any particular disjunct. For example, ‘A kills B’ may not entail any particular disjunct of the three listed in (DTC1). It may be that while A actually kills B, if, counterfactually, A had not killed B, C would have done. Hence, B’s death would not depend counterfactually on A’s actions, and B’s death could not be manipulated via A. So one cannot say that A’s killing B implies that B’s death depend on, or was manipulable via A. Furthermore, killing may not imply local transference of some physical quantity from A to B. Suppose A kills B via guillotine. No physical quantity (for example, energy or momentum) is transferred from A to the guillotine blade; A merely releases gravitational potential energy that was already stored in the raised blade. 7 So the concept ‘kill’, absent any further contextual information about the manner of killing, is as causally thin as ‘cause’ itself. Some verbs are not causal at all. For example, the statements “I have a blue shirt” or “I am twelve stone” are not causal claims. A verb is only causal if it entails ‘cause’ or one of the sufficient disjuncts. Each causal relation in the world, assuming that (DTC1) is correct, corresponds to one (or more) of the three disjuncts in (DTC1), and so has more ‘fine-grained detail’ than is implied by ‘cause’ alone. The knowledge that the word ‘cause’ applies, however, does not tell us which of the disjuncts applies. One might ask at this point why one should not measure the causal content of a concept by the number of criteria that are entailed by it, rather than by the number of disjuncts entailed. Such a measure would have undesirable and counterintuitive consequences, however. If we were to take all criteria to count as causal content, then any concept that entailed any of the criteria would count as having causal content. For example, the concept ‘adjacent’ would have causal content since it entails locality. Yet it seems counterintuitive to describe this relation as having causal content. It does seem intuitive to say that a relation involving local transference, on the other hand, has causal content. 4. Causal Thickness, Typicality and Borderline Cases A concept that is causally thin is not necessarily either an atypical or a more borderline case of causation than is a causally thick concept. These notions are rather different in nature and should not be conflated. For instance, cases of causation that involve only a single disjunct in (DTC1) - counterfactual dependence, for example – can intuitively be perfectly clear cases of causation. It may sometimes be the case that if one concept entails more disjuncts than another, it is judged to be more typically ‘causal’, but typical criteria should not be confused with criteria that are constitutive of a relation’s being causal. The fact that robins are judged to be more typical birds than penguins, for instance, does not entail that penguins lack some constitutive ‘birdcriteria’ that robins possess. 5. In Favour of the Disjunctive Theory of Causation (DTC) is not subject to the problems faced by Cartwright’s pluralistic account, since it renders the causal content of causal concepts clear rather than leaving it mysterious, and hence makes the basis of causal pluralism clear. (DTC) has the advantage over univocal analyses of causation of being able to explain the continuing historical failure of those univocal analyses. I have not intended to provide a fully worked-out defense of DTC. I have said little about its content, focusing instead on its logical form. I do not rule out that possibility that a univocal analysis of causation may be forthcoming, but the only univocal theories that currently appear to have even a remote chance of success are generally extremely complex and epicyclic. It can requires a lot of intellectual labour to even determine what the theoretical verdicts of some of these theories are. If they are intended to provide an account of our ordinary folk causal judgments, they lack psychological plausibility, particularly when contrasted with the clarity and simplicity of (DTC). 6. Conclusion 7 See Schaffer (2000) ‘Causation by Disconnection’ for extended discussion of similar examples. 4 The Disjunctive Theory of Causation agrees with Cartwright’s thick causal concepts account on the following points: 1. It is pluralistic. 2. Its logical form is disjunctive. 3. It explains why univocal theory of causation can succeed. 4. The causal content of some concepts outstrips that of the bare word ‘causal’. DTC disagrees with Cartwright’s account, however, in the following ways: 1. It is formulated in terms of general criteria rather than in terms of thick causal concepts. 2. It thereby provides an account of why certain verbs and relations are causative rather than taking this to be primitive, and provides a metric for quantifying their causal content. 3. The reason that no univocal analysis can succeed is that there is no individually necessary and jointly sufficient set of constitutive criteria, as opposed to there being some mysterious excess causal content in each causal verb. References Cartwright (2007) Hunting Causes and Using Them. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. Gaut (2000) ‘Art as a Cluster Concept’, in Theories of Art Today, ed. Carroll… Hall (2004) ‘Two Concepts of Causation’, in Causation and Counterfactuals, Collins Hall and Paul, eds. (2004) MIT Press. Boston. Hitchcock (2007) ‘How to Be a Causal Pluralist’, in Thinking About Causes, ed. Machamer and Wolters. Collins Hall and Paul, eds. (2004) Causation and Counterfactuals, MIT Press. Boston. Lewis (1973) ‘Causation’. Journal of Philosophy… Longworth (2006) Ph.D. dissertation Causation, Counterfactual Dependence and Pluralism. University of Pittsburgh. Machamer and Wolters, eds. (2007) Thinking About Causes, University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. 5