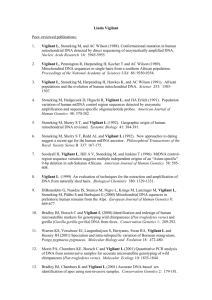

Jarvenpaa and Majchrzak Vigilant Interaction ISR Sept 2010

advertisement

1 Vigilant Interaction in Knowledge Collaboration: Challenges of Online User Participation Under Ambivalence Sirkka L. Jarvenpaa and Ann Majchrzak Abstract Online participation engenders both the benefits of knowledge sharing and the risks of harm. Vigilant interaction in knowledge collaboration refers to an interactive emergent dialogue in which knowledge is shared while it is protected, requiring deep appraisals of each others’ actions in order to determine how each action may influence the outcomes of the collaboration. Vigilant interactions are critical in online knowledge collaborations under ambivalent relationships where users collaborate to gain benefits but at the same time protect to avoid harm from perceived vulnerabilities. Vigilant interactions can take place on discussion boards, open source development, wiki sites, social media sites, and online knowledge management systems and thus is a rich research area for information systems researchers. Three elements of vigilant interactions are described: trust asymmetry, deception and novelty. Each of these elements challenges prevailing theory-based assumptions about how people collaborate online. The study of vigilant interaction, then, has the potential to provide insight on how these elements can be managed by participants in a manner that allows knowledge sharing to proceed without harm. 1. Introduction Increasingly, online participation exposes individuals to new ideas, prospective ties, and the thrill of fast paced knowledge collaboration. However, it also exposes those same actors to perceived vulnerabilities (Mitchell et al 2005). For example, in a Wikipedia conflict below, the parties started out co-editing an article which evolved into both parties feeling bullied and cyber-stalked by the other. A summary of the Wikipedia arbitration that ensued follows: “Fault on both sides. Rightly or wrongly. C feels bullied by W. This has caused her to overreact to W’s criticism of her and the overreaction has triggered more criticism. It has led to C commenting on W’s mental health and accusing her of stalking, and W and her friends as well as various anonymous IPs commenting on C’s mental health with blocks of increasing length handed out to C who was identified [by a third party based on some mining of the Wikipedia data] as the culprit in stalking W. Both women have been editing in areas in which they have emotional investment, and that has contributed to the strength of feeling and the personality clash. The result is two very upset women, one of whom has wikifriends (W) who rally round to support her, and the other of whom 1 2 doesn’t. The disparity strengthens C’s sense of isolation and feeling that she’s being bullied.” C was banned indefinitely from Wikipedia, with C’s response posted on a different forum as: “I was mistaken about W being the same person who has stalked me for 10 years and apologized for it...but I made that mistake because W was stalking me in her own right in a way that, in the beginning seemed so remarkably similar. I don't ever want to go back to the spiteful kindergarten playground that is Wikipedia.” (NOTE: Identities and words are disguised to protect the privacy of online personas). This example illustrates one of many types of perceived vulnerabilities that can occur when individuals share their knowledge online. In this example, the perceived vulnerability was that of both parties devolving their collaboration to cyber-stalking each other. In other cases of online participation, the perceived vulnerabilities of corporate sabotage, fraud, or reputation harm may ensue (Mitchell et al 2005). These are serious problems. Teenagers are found on the web and become so victimized that they commit suicide (Kotz 2010). A family is tortured for years when the badly deformed body of their dead daughter after a traffic accident is posted on the web and won’t fade away (Bennett 2009). Individuals’ health records are being manipulated so that individuals are losing their health insurance (Sweeney 2010). Individuals have their identities stolen (Pavlou et al 2007). Companies lose reputation when competitors learn and share information publicly (Majchrzak and Jarvenpaa 2005). Yet, every day, millions go on the web, share personal information and ideas conducive to creating new intellectual capital and come away with satisfied interactions that do not suffer from invasion, abuse, or deception (Pew Research Center 2009).When abuse happens, far too often, the blame is placed on either the perpetrator or the victim: the victim had low self-esteem, was not adequately supervised, was too needy, didn’t follow the “rules of engagement” (Sweeney 2010) or the perpetrator was Machiavellian, a sociopath, or worse (Liu 2008). Yet, these are the easy answers that do not help us understand how individuals and companies can use the internet for productive dialogue – dialogue that intermixes both sharing and protection. In this commentary, we are focused on the research question: How do individuals, who are aware of these perceived vulnerabilities, maintain their online interaction in a manner that allows them to both share their knowledge and protect themselves from these vulnerabilities? 2 3 In this commentary, we describe perceived vulnerabilities present in risky collaborations. We suggest that online knowledge collaborations are high on ambivalence and individuals need to manage this ambivalence by sharing and protecting simultaneously. We advance the concept of “vigilant interaction” to describe the type of behaviors that participants use to successfully share and protect. We identify three elements of vigilant interactions that require further research, explaining how each of these elements challenges existing theorizing about knowledge collaboration. We conclude with implications for research approaches. 2. Online Knowledge Collaboration Knowledge collaboration is defined as the sharing, transfer, recombination and reuse of knowledge among parties (Grant 1996). Collaboration is a process that allows parties to leverage their differences in interests, concerns, and knowledge (Hardy et al 2005). Knowledge collaboration online refers to the use of the internet (or intranet) to facilitate the collaboration. Much online collaboration occurs in public forums including practice networks and online communities (Wasko et al 2004). Online knowledge collaboration can take many forms. It could involve an individual posting a question to a discussion forum and then engaging in a process of reflecting on incoming responses and posting clarifying questions (Wasko and Faraj 2005, Cummings et al 2002). The collaboration could involve parties engaging each other in surfacing contested assumptions (Gonzales-Bailon et al 2010). The collaboration could be intentioned to help coordinate sub-projects as in the case of open source software development (von Hippel and von Krogh 2003). Collaborations online often take the form of a dialogic interaction style, variously referred to in off-line and on-line contexts as “expertise-sharing” (Constant et al 1996), “help-seeking (Hargadon and Bechky 2006), or “hermeneutic inquiry” (Boland et al 1994). 3. Perceived Vulnerabilities in Online Knowledge Collaborations In these online knowledge collaborations, a range of factors exist that create the possibility of vulnerabilities. For example, vulnerabilities are made possible when social identities are socially ambiguous as individuals share only partial information about their identities, if at all, and often change identities (Knights et al 2001), making it difficult for participants to be held accountable for their actions. In the opening story, for 3 4 example, it took the efforts of third parties and a Wikipedia mining tool to determine if C was the individual cyberstalking W. Vulnerabilities are also present when individuals do not share common interests, even though they are both contributing to the same forum (Brown et al 2004). In the opening story, later analysis indicated that C’s interest in developing the Wikipedia article was focused on ensuring that the opinions of a particular constituency (patients) were represented while W’s interest was focused on developing a well-cited encyclopedic article that would be well-regarded in the medical establishment. Collaborating parties, then, may have competing interests, even though they are contributing to the same online forum (Prasarnphanich and Wagner 2009). Finally, perceived vulnerabilities increase in the online context because of limited social cues that are provided online as well as the lack of availability of information for triangulation (Walther et al 2009). Common ground can be missing leading to miscommunication and misattribution (Walther et al 2009). For example, in the opening story, C had misattributed to W the cyber-stalking she was experiencing. These perceived vulnerabilities are not limited to the cyber-stalking and cyber-bullying depicted in the opening story. They include fraud and stealing, as when private information is gained by another party during the collaboration that is later used to fraudulently purchase goods. Perceived vulnerabilities also include reputation loss as when information that is privately shared among online collaborators might be misunderstood or perceived negatively by a third party such as a customer or competitor is then shared with those third parties (Scott and Walsham 2005, Clemons and Hitt 2004). Although perceived vulnerabilities are faced in online collaborations by firms as well as individuals, in the rest of the paper we will primarily focus on individuals. Individuals collaborate online in order to address a problem or opportunity. They are engaging “friends” within their social networking tool to take advantages of the opportunities for entertainment, coordination, selfesteem, and social identity development (e.g., Walther et al 2009). They are engaging in a forum conversation to get answers to a question or to help others get their answers. They are adding content to an open source production environment to share their perspectives on the content. Thus, individuals are focused primarily on the knowledge sharing aspect of collaboration: what knowledge to share with others in order to obtain the knowledge they need. 4 5 Nevertheless, the perceived vulnerabilities are potential second order consequences of the online collaborations, and as such need to be managed as well. Much of the literature and theorizing about knowledge collaboration is about how to increase knowledge sharing (Becerra-Fernandez and Leidner 2008). By applying such theories as social exchange and social capital, we have learned much about the factors that influence knowledge sharing (Wasko and Faraj 2005). However, we know much less about how people protect themselves as they share. For example, we do not know what sequences of behaviors in an online interaction are likely to lead to knowledge collaboration outcomes that do not only solve the initiating problem or interest of the party, but also prevent harm. In the opening story, the behaviors escalated to a point where harm was incurred and perpetrated by both parties. As researchers of online behavior, we would ideally like the parties to have continued to collaborate in a productive exchange without the escalation. Much current literature on online deception and fraud has focused on what we refer to as a “constrain or withdraw” approach. In this important research, the information that participants need in order to identify parties that could pose a risk is examined with the intention that the parties will either withdraw from further collaboration or will be able to take contractual steps to constrain the other parties’ behavior. For example, research on online purchasing behavior has identified the information that customers need in order to decide if an online supplier should be a “trusted” recipient of the customer’s private information (e.g., Pavlou et al 2007) or should be a trusted supplier for online purchases (e.g., Ba and Pavlou 2002). This research has led to the important role of reputation monitors that have been more broadly applied to the online forum context (e,g., Pavlou et al 2007) . The implication is that the customer or participant will not collaborate with others with poor reputation. Similarly, the research on formal mechanisms to manage online collaborations has encouraged the use of formal contracts to constrain others’ behaviors (Aron et al 2005). The implication is that, with the proper enforcement mechanisms, others’ behaviors can be managed to create less risk. In many online contexts, however, parties still collaborate with each other despite the risks, despite unknown information about the other party’s reputation, and despite having few formal mechanisms to prevent harmful behavior. That is, they do not withdraw from the collaboration, because withdrawal may be problematic for a variety of reasons. Withdrawal is problematic because it deprives individuals of the community’s benefits 5 6 (Paul 2006), as when a prostate cancer patient stays in an online prostrate cancer support group to obtain the advice of survivors despite the risks associated with sharing details about his situation (Broom 2005). Withdrawal is also problematic for the community since, as participants withdraw, there is less diverse experiences to leverage. For example, in the opening case, C’s decision to not continue contributing to Wikipedia (even under a non-blocked new persona) deprives the Wikipedia community of a particular perspective (that of the patient), that if effectively leveraged might have resulted in a richer article. In sum, there are some online collaborations that involve few known vulnerabilities, such as with anonymous interactions (Rains 2007). In other online collaborations, the parties may be identified but choose to ignore the dangers, such as when a teenager interacts with someone in a discussion forum without concern for whether the person’s identity is true or false (Krasnova et al 2010). Other online interactions are ones in which the parties are aware of the risks, and are able to take steps to essentially avoid or eliminate the risks, such as by disaggregating the work (Rottman and Lacity 2006), creating contracts or agreements with enforcement mechanisms (Clemons and Hitt 2004), or withdrawing. However, there are online collaborations where the parties are aware of the dangers of online participation, cannot take steps to eliminate them, and still engage in the collaboration. It is these risky online collaborations that we are focused on. Individuals and organizations engage in these risky online collaborations despite research that would suggest that they should protect themselves by steering away from these collaborators and, if that is not possible, contractually and formally constraining the collaborators’ behaviors. Research is needed to understand how individuals can succeed in risky online collaborations such that they successfully share their knowledge in a manner that does not result in harm. 4. Online Knowledge Collaborations as “Ambivalent” Relationships Collaborations in which the parties are aware of the dangers of online participation, do not ignore them, are unable to eliminate them, and still engage in them describe what we refer to as “ambivalent” collaborations. The collaboration is ambivalent because the user approaches the community or other parties with a promise of collective and private benefits, but is concerned about the perceived vulnerabilities that such a collaboration creates. One way to understand the ambivalence of these collaborations is to examine them from the orientation of trust. Although there are many different definitions of trust as well as distrust in the literature, Lewicki et al (1998, 6 7 2006) argues that trust and distrust are two different qualitatively distinctive assessments that one party can make about another party. Trust is defined by Lewicki et al (1998) as a positive expectation of the conduct of the other party in a specific situation involving perceived risk or vulnerability. In contrast, distrust is a negative expectation regarding the conduct of the other party in the specific situation involving perceived risk or vulnerability. While trust may help to decrease perceived vulnerabilities in teams of common goals and knowledge of each other (Staples and Webster 2008), in situations such as those found in online contexts where a common goal cannot be presumed and where the parties may not know each other, trust – or a positive expectation of the other party – may actually increase a party’s vulnerability because trusting parties are less likely to protect themselves (Grazioli and Jarvenpaa 2000). Thus, in such contexts, trust needs to be coupled with distrust, creating the ambivalence. In contrast to some models of trust (e.g., Mayer et al 1995), Lewicki et al (1998) argue that, in a relationship, trust and distrust are two separate constructs and they do not need to be in balance or even consistent with each other. Instead, they argue, relationships are multi-faceted enabling individuals to hold conflicting views about each other since trust can develop in some facets of a relationship with another person and distrust developing in other facets of that same relationship. Moreover, since balance and consistency in one’s cognitions and perceptions are likely to be temporary and transitional in ambivalent relationships, parties are more likely to be in states of imbalance and inconsistency that do not promote quick and simple resolution. For example, Mancini (1998), in an ethnographic field study on the relationship between politicians and journalists in Italy, found that politicians trusted journalists enough to share some information with them but distrusted the journalists to verify the accuracy of their information before publication. Collaborations in which the parties are aware of the dangers of online participation, do not ignore the risks, yet are unable to eliminate the risks, and still not withdraw from the interaction require the parties to hold both trusting and distrusting views of the other parties. These views create an ambivalence that must be managed by the parties. 5. Vigilant Interactions Individuals in ambivalent online collaborations are functioning at the intersection of knowledge sharing and protection. According to Lewicki et al (1998), trust is characterized by hope and faith while distrust is expressed by wariness, watchfulness, and vigilance. In a high trust/high distrust situation, Lewicki et al (1998) recommend 7 8 limiting interdependencies to the facets of the relationships that engender trust and to establish boundaries on knowledge sharing for those facets that engender distrust. Unfortunately, this presumes that the facets of the relationships that engender trust and distrust are clearly identifiable, a possibility for the types of relationships that Lewicki et al (1998) reviews. In contrast, though, in online open forums with socially ambiguous identities and participants who have little knowledge of each, we find that research has not yet clearly established that collaborating parties are functioning with the knowledge of which facets of the collaborative relationship engender trust and which facets engender distrust. Instead of creating static boundaries between facets of the relationship, then, we suggest that it is likely that the parties are not making clearly definable boundary distinctions, but rather are engaged in a risky generative dance (Cook and Brown 1999). Vigilance then becomes not simply a state of being, but an interactive emergent dialogue in which knowledge is shared while it is protected. We refer to the active dialogue that ensues in this risky dance as “vigilant interaction.” Vigilant interaction requires deep appraisals of the other parties’ actions in order to evaluate how each action taken by the other party influences the outcomes of the collaboration. Since collaborative knowledge sharing generally unfolds emergently (Paul 2006), vigilant interactive dialogue is likely to unfold emergently. That is, in a vigilant interaction, as Party A makes an online contribution, Party B examines Party A’s actions to determine how it might influence the outcomes of their collaboration, which then affects Party B’s response, which is also appraised, and so on. Vigilant collaborators protect themselves by making choices about what to share, when, and how as one emergently interacts with others. Vigilant collaboration, therefore, is inherently adaptive, involving sharing that simultaneously probes, monitors reactions to assess perceived vulnerabilities, and safeguards information that could be used in a way to create a vulnerability for the party during the interaction. While there has been substantial research on knowledge collaboration under risk, there has been relatively less research on the nature of vigilant interactive dialogue – that is, how individuals manage the vigilant interaction in a sustained manner over time to continue an ambivalent collaboration where they share but avoid the harm from sharing. Rarely have online studies examined vigilant interactions from the theoretical perspective of ambivalent relationships. The online research has empirically validated the presence of both trust and distrust as two separate 8 9 constructs and how different technology features (i.e., recommendation agents) have differing impacts on these two constructs (Komiak and Benbasat 2008). However, the online research has not examined the implications of ambivalence on how individuals share and protect in knowledge collaborations. While there has been little research on how vigilant interactive dialogue can help individuals to simultaneously share and protect their knowledge, existing theorizing suggests that maintaining vigilance during a knowledge collaboration requires the interactors to expend substantial cognitive resources. Several researchers (Lewicki et al 1998, Scott and Walsham 2005, Weber et al 2005) describe vigilant knowledge processes as highly deliberate rational acts in which people engage in careful processing of information, challenging assumptions, probing for both confirming and disconfirming evidence, being intensely sensitive to the other party. Such processes are cognitively demanding and require a willingness to invest considerable resources. Unfortunately, there are ample examples in online communities of individuals not investing in these cognitive resources even where there are explicit and strong reminders of possible vulnerabilities (Grazioli and Jarvenpaa 2000). There are many motivational reasons why individuals may not invest in these cognitive resources. They may find maintaining trust and distrust as too stressful. To reduce stress and to reduce the amount of information processing, people decide to trust even in situations where trust seems unwise and potentially dangerous (Weber et al 2005). The prevailing organizational or societal values can also create a bias toward reducing tension and rely on general choices such as a woman’s decision to trust new people “until they give her some reason not to trust them” (McKnight et al 1998, p. 477). Research, then, is needed to understand why some individuals are willing to invest the cognitive resources in vigilant interactions while others are not. While research on motivational reasons for an individual to willingly engage in vigilant interactions is needed, research on motivation will still not address the question of how individuals engage in this cognitively difficult task of vigilant interaction. What are the sequences of actions interactors take to successfully minimize the effect of harm as they meet their collaboration needs? What helps to distinguish successful vigilant interactions from less successful ones? To begin to address these questions, we identify below three elements that have emerged in our research on online and ambivalent relationships that seem to describe most vigilant interactions. These elements challenge assumptions in existing theories that have been applied to knowledge sharing and 9 10 collaboration. We believe that by encouraging research along these veins, new theory development will ensue that will not only help to explain vigilant interaction, but help to explain knowledge collaboration in conflicting and mixed-motive settings. 5.1.Element of Trust Asymmetry We assert that one element that describes many vigilant interactions is their trust asymmetry. Trust asymmetry is defined as when party A trusts party B, but party B distrusts party A or finds trust immaterial to the relationship (Graebner 2009). The presence of trust asymmetry has been documented in off-line contexts (Weber et al 2005, Graebner 2009). This research has found that not only some parties to a collaboration experience different appraisals of trust and distrust for each other, but that these appraisals may be inaccurately perceived by each party (Graebner 2009). That, is one party may assume the other party distrusts them, but be wrong. Moreover, given the context-specific nature of trust appraisals (Lewicki et al., 1998), these appraisals are likely to change over time as contexts change, leading to fluctuations over time in the trust asymmetry. We suggest that the high social complexity of ambivalent online collaborations makes trust asymmetry prevalent, despite the need to maintain both trust and distrust (Grazioli 2004). Individuals in online collaborations often develop one-sided dependencies in which one party depends for emotional or task reasons on the other party without the dependency being reciprocated (Rice 2006). For example, as one party is disclosing increasingly more personal health information to get suggestions for possible alternative treatment options from the other parties, the sharing party can become increasingly emotionally dependent on the other parties, without necessarily the other parties being emotionally dependent on that party. The one party’s dependency and the other parties’ lack of dependency creates a trust asymmetry. The implications for vigilant interactions, we argue, is that the interactors are engaged in interactions that involve trust asymmetries. Moreover, the interactors are making several appraisals as they interact: their level of trust/distrust in the other party, the other party’s level of trust/distrust in them, and the accuracy of these appraisals. Finally, these appraisals are likely to change as other parties act and react to behaviors engaged in by both the interactors as well as the third parties. 10 11 Applying the notion of trust asymmetry to online knowledge collaboration challenges the conventional thinking that trust between the two parties is symmetric (Serva et al 2005). Similarly, trust asymmetry challenges the notion that, in the face of asymmetry, online participants will withdraw from the situation (Pavlou et al 2007). Since vigilant interactors will need to engage in the trust asymmetric situation despite the asymmetry, trust asymmetry also challenges the notion that individuals will engage in the relationship to the extent to which they can achieve symmetry or trust over time (e.g., Zahedi and Song 2008, Kanawattanachai and Yoo 2002, Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1999). Finally, the changing nature of trust asymmetry and the lack of an ability to validate the others’ trust appraisals of oneself challenges the notion that appraisals of trust can be made more accurate over time (Serva et al 2005). Therefore, research is needed that improves our understanding of how successful vigilant interactors manage their trust asymmetries. Do they use third parties to both remind them of the potential for an asymmetry? Do they use third parties to help diffuse the dependencies that can create the asymmetry? How do the asymmetries morph over time as people act and react? What criteria do vigilant interactors use to decide if an asymmetric interaction is too asymmetric to warrant continued participation? 5.2. Element of Deception The second element that we assert describes vigilant interactions is the presence of deception by all parties in the interaction. We build on the notion of Buller and Burgoon (1996) that deception is an interactive process where both the sender and receiver need to be considered. Deception involves knowingly transmitting messages with the intent to foster false belief or conclusions (Grazioli 2004). Deception is commonplace online (Hancock et al 2004, Mitchell et al 2005). Some have attributed the high level of online deception to a high tolerance of divergent and contrarian behaviors that would be considered inappropriate or dangerous offline (Herring et al 2002). In an online interaction context, we suggest that deception may be so prevalent because it is used by interactors as a strategy to manage perceived vulnerabilities. Individual participants may be managing their perceived vulnerabilities proactively by perpetrating a “lie”, i.e., an incomplete or inaccurate self-portrait. Deceptions may be of varying degrees, from creating a biased view of oneself (such as designing avatars with 11 12 personalities and physical features that represent a person’s ideal rather than real self), to creating partial views (such as by sharing some information about oneself, but not all information), to intentionally misleading views (such as by leading others to believe the person is intrinsically interested in the Wikipedia article but in fact is being paid by a public relations firm to remove negative statements about his client). Importantly, deceptions may not be for the exclusive purpose of gain or advantage as depicted in the deception literature (Grazioli 2004), but including a broader set of reasons such as protecting one’s own identity from exploitation, minimizing conflict in existing relationships, reducing others’ processing demands, encouraging fun, and curiosity (Walther 2007). Despite the deception, others with similarly incomplete or inaccurate self-portraits need to act on their beliefs about the accuracy of the other’s self-portraits. The fact that successful vigilant interactors may be engaged to some extent in deception challenges several assumptions of theories used to explain online knowledge collaboration. When vigilant interactors communicate information online, they may not be striving for what has been referred to as a common ground (Clark and Brennan 1974) or shared understanding (Teeni 2001) since it may be this shared understanding that they are trying to protect – as when they don’t want the other party to know their name or their background or the sources of the information they are sharing. Participants may also not be seeking accurate identity communication of their self, as has been suggested in research on online participants (Ma and Agarwal 2007). That is, individuals’ self-views may intentionally disagree with others’ appraisals of self. Attribution differences between a sender and receiver may be desired, not an objective for reduction (Hansen Lowe 1976). Consequently, reputation rankings that are currently viewed today as a mechanism for constructing accurate representations of others’ identities (Ma and Agarwal 2007) may be intentionally manipulated to be an inaccurate representation. Research is needed, then, to understand how successful vigilant interactors manage the different deceptions that they perpetrate and receive from others. Do they divide their identities into different facets, seeking verification for different identity facets from different people? Or do they not seek verification at all? How does a successful vigilant interactor stay in control of these facets so that those parts of the identity they want verified by certain others are verified and those other parts they don’t want to be verified are not? 5.3 12 Element of Novelty 13 A third element we assert as describing vigilant interactions is their novelty and the emotional response created by the novelty. Novelty may come in a form of new members, new content, and new ways of behaving (Faraj et al 2011). This novelty generates new forms of recombination and excitement that exemplify the diversity in an online environment. This emotional side of novelty becomes a critical element of vigilant interactions. In the pursuit of novelty, an individual is more likely to adhere to hedonic needs, such as sensation-seeking, greed, or pleasure. According to the theory of “visceral influence” describing online scammers’ behaviors (Langenderfer and Shrimp 2001), swindlers influence their targets by appealing to momentary hedonic-based drive states such as greed, fear, pain, and hunger. Individuals focused on their hedonic needs are less likely to be motivated to deeply process messages, focusing instead on the promise of hedonic fulfillment (Langenderfer and Shrimp 2001). Consequently, individuals driven by hedonic needs tend to be less attentive to others’ deceptions. Thus, the vigilant collaborator not only must detect when others’ novel behaviors create vulnerabilities, but also recognize when one’s own desire for novelty opens up opportunities for deception and exploitation. The role of emotions in these interactions questions prevailing assumptions about how people process information. Theories on dual information processing, particularly those involving validity-seeking such as elaborative likelihood model (Petty and Cacioppo 1986) and heuristic-systematic processing model (Chaiken and Trope 1999), argue that people will economize on cognitive resources for ascertaining the validity of information. Consequently, individuals will only engage in deeper processing when the participant judges the incoming information as relevant and important, without regard to emotions. Vigilant interaction requires deep processing and cognitive elaboration in order to establish validity of the other party’s intented meanings by scrutinizing each response and non-response of the other party. By assessing the reactions of others, the user needs to detect cues that indicate changing intentions such as less or more deception. Therefore, according to dual information processing theories, individuals are likely to engage in this deep processing when they judge the incoming information as relevant and important, without regard to emotions. The research on hedonic drive states in online contexts suggests, however, that emotions will play a strong role in vigilant interaction, rendering a taxing situation that exceeds the individual’s capacity to process information 13 14 (Wright et al 2010, Wright and Marett 2010). The taxing situation may push the user away from deep processing and cognitive elaboration to less effortful heuristic or peripheral information processing, even when the incoming information is highly relevant and important. The role of emotions then may question the assumption in dual information processing models about the role of relevance and importance in encouraging deep processing. For example, Ferran and Watts (2008) found that users in face-to-face meetings engaged in the deeper more systematic processing than those in a videoconferencing meeting, attributing the results to videoconferencing participants experiencing less salient social cues and difficulties in turn taking and conversational pacing. In contrast, we suggest that emotions may provide an alternative explanation for this online behavior of videoconferencing since videoconferencing was novel to the participants, engendering strong emotions that drove them away from deeper processing. Therefore, the presence of novelty in vigilant interactions requires us to consider emotions in the theories of dual information processing in online knowledge collaborations. Research is needed on the impact of novelty and emotions on vigilant interactors. How do vigilant interactors maintain an emotional balance between the negative emotion of stress caused by the ambivalence and the positive emotion of excitement caused by the novelty? How are third parties used to maintain this emotional balance? How do successful vigilant interactors monitor their emotions and use changes in their emotions to help identify when they may be exposing themselves to potential vulnerabilities? 6. Implications for Research Approaches The focus on vigilant interaction and the three elements have implications for research approaches. To understand how individuals both share and protect in vigilant interaction, we suggest that it is the interaction and how all the parties collaborate in that interaction that become the focal unit of analysis. The interaction includes the content and context of the interaction. These interactions are not simply the interactions of conversation – as would be found in a discussion forum. These interactions include much subtler and nuanced forms that social media provide, including links or selectively choosing with whom to associate, commenting on other comments such as by digging up or down others’ comments, deciding what to post on a wiki talk page versus a wiki article page, categories of people to include in one’s twitter list, and deciding what social network information one might 14 15 examine before joining a group or inviting other previously unknown individuals to join. The analysis of interactions requires examining action-reaction sequences among parties, the cues that interactors attend to over time, and how interactors respond emergently, quickly, and flexibly to others’ actions. Importantly, increasingly the interactions are no longer text based but rely on photos and other media, particularly as the knowledge collaboration moves to mobile Internet (Smith 2010). The online collaborations are also increasingly transcending online and offline media, requiring researchers to no longer limit one’s observations to the online behavior alone. As such, examining vigilant interactions require a broad perspective on the “interaction”, beyond a simple conversation. The three elements have specific implications for how to study vigilant interaction. Researchers should be mindful of not simply understanding whether A trusts or distrusts B, but whether A is aware of a trust asymmetry and takes action based on it. To understand whether an action is based on the awareness of trust asymmetry, the researcher needs to capture A’s impressions of the trust/distrust of B, how this impression impacts A’s trust in B, and a recognition that these appraisals may be wrong, with both parties varying in their knowledge of the accuracy of these appraisals. Without this fuller view of the asymmetric nature of the collaboration, the researcher may infer over-simplistic reasons why one party shares knowledge with another. The element of deception also has implications for how to study vigilant interaction. Deception can not be assumed to be a stable state of the interaction, but is likely to change as the interaction unfolds. How a researcher detects deception in an interaction, as well as detects if the parties are aware of the deception, is not an easy issue. Deception might be detected by revealing the intent of parties, but obtaining accurate intent by interviewing or surveying the party may be unlikely. Moreover, the reported intent is likely to be a static account. The detection and evolution of intent might require focusing on the content and developing proxy measures on the basis of an analysis of past interactions not just between the two parties, but incorporating other third parties as well. If such an analysis suggests inconsistencies in how one portrays oneself over time, different intentions associated with different degrees of inconsistencies may be inferred. Sudden changes in how a party responds to revealed information may also suggest a change in intent. A caution needs to be exercised in the use of these techniques as they are not immune from malicious manipulation by either the target of research or the researcher. The novelty element also has implications for research approaches. 15 16 Novelty requires uncovering the emotions that impact interaction. Uncovering emotions is particularly difficult when subjects can not be directly interviewed to report their emotions, as is often the case with online knowledge collaboration. Researchers, then, need to develop proxy measures. This might involve analyzing emoticons, examining norms, or looking at the history of the person in other interactions, inferring the presence of emotions when interactions are different than expected historically. Many thorny issues exist in terms of ethics of Internet research. We raise two issues. First, from whom, how, and when should researchers obtain consent? The answer depends on the ability to determine who the relevant parties are in online collaborations. van Dijck ( 2009) argues that agency in online knowledge collaborations is far from clear as it is often impossible to identify who is participating and who has contributed what. Moreover, not all of the interactions between parties will take place in the public forum that the researcher is observing, as when private channels such as email are used to continue a discussion that the parties no longer want to remain public. Second, how should we report our research results to maintain the privacy and security of those studied? Online personas are identifiable with persistent history over long periods of time and so are the tracks that the personas have left even when the content has been disembodied from the personas. Should only aggregate data be reported unless the consent of online personas are obtained? Or is the practice that we used in this paper – of modifying words and persona names - sufficient? 7. Conclusion This commentary calls for increased understanding of how individuals can use the Internet in risky collaborations by intermixing both sharing and protection. By understanding successful vigilant collaborations, researchers can have a major impact on business and society in learning and disseminating knowledge about how to encourage those who don’t engage in vigilant collaboration to do so. The teenager who ignores the risks when interacting with others in a discussion forum may then have ways to interact vigilantly; the security professional will be able to turn to a listserve and gain valuable unique knowledge that otherwise would have been missed in our war on terrorism. To help begin to address productive dialogue in risky collaborations, the perspective of ambivalent relationships can provide us with a theoretical foundation that brings to the foreground that users need to hold both 16 17 trusting and distrusting view of the other parties. These views create the ambivalence that must be managed by the parties in vigilant interaction. Vigilant interactions require attending to and managing three elements: trust asymmetry, deception, and novelty. In vigilant interactions, trust asymmetries will arise as interactors develop one-way dependencies on each other. In vigilant interaction, parties deceive each other to varying degrees throughout the interaction. In vigilant interaction, the novelty of online participation heightens emotional response to interaction, making it more difficult to deeply process incoming messages and detect deception and asymmetries. Research is needed that examines how these elements are managed by successful vigilant interactors. Such research is not only of theoretical significance as it challenges the prevailing assumptions of knowledge collaboration. Such research is of major practical significance as well. References Aron R., E.K.Clemons, S. Reddi. 2005. Just right outsourcing: Understanding and managing risk. J. Management Inform. Systems 22( 2 ) 37-55. Boland, R. J., R.V.Tenkasi, D. Te’eni. 1994. Designing Information Technology to Support Distributed Cognition. Organ. Sci. 5(3) 456-475. Ba, S., P.A. Pavlou. 2002. Evidence of the Effect of Trust Building Technology in Electronic Markets: Price Premiums and Buyer Behavior. MIS Quart. 26 (3) 243-268. Becerra-Fernandez, I., D. Leidner (eds). 2008. Knowledge Management: An Evolutionary View: Advances in Management Inform.Systems, M.E. Sharpe Inc. Armonk, NY. Bennett, J. 2009. A Tragery That Won’t Fade Away. http://www.newsweek.com/2009/04/24/a-tragedy-that-won-tfade-away.html. Broom, A. 2005. The eMale: Prostate Cancer, Masculinity and Online Support as a Challenge to Medical Expertise. J. of Soc.41 (1) 87-104. Brown, H.G., M.S. Poole, T.L. Rogers. 2004. Interpersonal Traits, Complementarity, and Trust in Virtual Collaboration. J. Management Inform. Systems 20 (4) 115-137. Buller, D.B., J.K. Burgoon. 1996. Interpersonal Deception Theory. Comm. Theory, 6(3) 243-267. Constant, D., L. Sproull, S. Kiesler. 1996. The kindness of strangers, Organ. Sci. 7(2) 119-135. Chaiken S.,Y. Trope.1999. Dual Process Theories in Social psychology. Guildford Press, New York, N.Y. Clark, H.H., S.E. Brennan. 1974. Grounding in Communication. L. B. Resnick, J. Lewine, and S. D. Teasley, eds.Perspectives on socially shared cognition. The American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. 127-149. 17 18 Clemons, E.K., L.M.Hitt. 2004. Poaching and the Misappropriation of Information: Transaction Risks of Information Exchange, J. Management Inform. Systems 21 (2) 87-107. Cook, S.D.N., J.S. Brown. 1999. Bridging epistemologies: The generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing. Organ. Sci. 10(4) 381-400. Cummings, J. N., L. Sproull, S. Kiesler. 2002. Beyond Hearing: Where real world and online support meet. Group Dynamics 6(1) 78-88. Faraj, S., S.L. Jarvenpaa, A. Majchrzak. 2011.Knowledge Collaboration in Online Communities. Organ. Sci. forthcoming. Ferran, C., S.Watts. 2008.Videoconferencing in the Field: A Heuristic Processing Model. Management Sci.54 (9)1565-1578. Gonzales-Baion, S., A.Kaltenbrunner, R.E. Banchs. 2010. The Structure of Political Discussion Networks: A model for the Analysis of Online Deliberation. J. Inform. Technology 25 230-243. Graebner, M.E. 2009. Caveat Venditor: Trust Asymmetries in Acquisition of Entrepreneurial Firms. Acad. Management J. 52( 3) 435-472. Grant, R.M. 1996. Prospering in dynamically- competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organ. Sci.7(4) 375–386. Grazioli, S. 2004 . Where did they go wrong? An analysis of the failure of knowledgeable internet consumers to detect deception over the internet. Gr. Dec. Negot. 13149–172 Grazioli, S., S.L. Jarvenpaa. 2000. Perils of Internet Fraud: An Empirical Investigation of Deception and Trust with Experienced Internet Consumers, IEEE Trans.on Syst., Man, and Cybernetics 30 (4) 393-410. Hancock, J. T., J. Thom-Santelli, T. Ritchie. 2004. Deception and design: The impact of communication technologies on lying behavior. Proc., Conf. on Computer Human Interaction 6 130-136. Hansen, R. D., C. A. Lowe. 1976. Distinctiveness and consensus: Influence of behavioral information on actors and observers attributions. J. Personality Soc. Psych. 34(3) 425–433. Hardy,C., T.B. Lawrence, D. Grant. 2005. Discourse and Collaboration: The Role of Conversations and Collective Identity. Acad.Management Rev. 30 (1) 58-77. Hargadon, A.B., B.A. Bechky. 2006. When Collections of Creatives Become Creative Collectives: A Field Study of Problem Solving at Work. Organ. Sci.Vol. 17 Issue 4, p484-500. Herring, S., K. Job-Sluber, R. Scheckler, S. Barab. 2002. Searching for Safety Online: Managing “Trolling” in a Feminist Forum.The Inform. Soc.18 371-384. Jarvenpaa, S.L., D.E. Leidner. 1999. Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organ. Sci. 10(6) 791-815. Kanawattanachai, P., Y. Yoo. 2007. The impact of knowledge coordination on virtual team performance over time. MIS Quart. 31(4) 783-808. 18 19 Kotz, P.2010. Phoebe Prince, 15, Commits Suicide After Onslaught of Cyber-Bullying From Fellow Students. http://www.truecrimereport.com/2010/01/phoebe_prince_15_commits_suici.php Knights, D., F. Noble, T. Vurdubakis, H. Willmott. 2001. Chasing Shadows: Control, Virtuality, and the Production of Trust. Organ. Studies, 22, 2, 311-336. Komiak, S.Y.X., I. Benbasat. 2008. A Two-Process View of Trust and Distrust Building in Recommendation Agents: A Process-Tracing Study. J. Ass. for Inform. Systems 9 (12) 727-747. Krasnova, H., S. Spiekermann, K. Koroleva, T. Hildebrand. 2010. Online Social Networks: Why We Disclose., J.Inform. Technology 25 109-125. Langenderfer, J. T.A. Shrimp. 2001. Consumer Vulnerability to Scams, Swindles, and Fraud: A New Theory on Visceral Influences on Persuasion. Psych. & Marketing 18 (7)763-783. Lewicki, R.J., D.J. McAllister, R.J. Bies. 1998. Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Acad. Management Rev. 23 (3) 438-458. Lewicki, R.J., E.C. Tomlinson, N. Gillespie. 2006. Models of interpersonal trust development: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. J. Manage. 32(6) 991-1022. Liu, C.C. 2008. Relationship between Machiavellianism and knowledge-sharing willingness. J. Business Psych. 22 233-240 Ma M., R. Agarwal. 2007. Through a Glass Darkly: Information Technology Design, Identity Verification, and Knowledge Contribution in Online Communities. Inform. Systems Res. 18(1) 42-67. Majchrzak, A., S.L. Jarvenpaa. 2005. Information Security in Cross-Enterprise Collaborative Knowledge Work. Emergence 6(4) 4-8. Mancini, P. 1993. Between trust and suspicion: How political journalists solve the problem. European J. Comm. 8 33-51. McKnight, D.H.,L.L. Cummings,.N.L. Chervany. 1998. Initial trust building in new organizational relationships. Acad. Management Rev. 23 472-490. Mayer, R.C.,J.H. Davis, F.D. Schoorman. 1995. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad Management Rev.20(3) 709-734. Mitchell, K.J. K.A. Becker-Blease, D.Finkelhor. 2005. Inventory of Problematic Internet Experiences Encountered in Clinical Practice. Professional Psych: Research & Practice 36(5) 498-509. Rains, S. A., 2007. The Impact of Anonymity on Perceptions of Source Credibility and Influence in Computer-Mediated Group Communication: A Test of Two Competing Hypotheses. Comm. Res. 34(1) 100-125. Paul, D.L. 2006. Collabortive Activities in Virtual Setting: A Knowledge Management Perspective of T Telemedicine. J. Management Inform. Systems 22 (4) 46-176. Pavlou, P.A. A. Liang, Y. Xue. 2007. Understanding and Mitigating Uncertainty in Online Exchange Relationships: A Principal-Agent Perspective. MIS Quart. 31 (1) 105-136. 19 20 Pew Research Center, 2009. 61% of American adults look online for health information. http://www.pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2009/The-Social-Life-of-Health-Information.aspx Petty, R.E. J.T. Cacioppo. 1986. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change, Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. Prasarnphanich, P., C. Wagner. 2009. The role of wiki technology and altruism in collaborative knowledge creation. J.Computer Inform. Systems 49 ( 4) 33-41. Rice, R.E. 2006. Influences, Usage, and Outcomes of Internet Health Information Searching: Multivariate Results from the Pew Surveys. Int, J.Medical Informatics 75 (1) 8-28. Rottman, J.W., M.C. Lacity. 2006. Proven Practice Effectively Offshoring IT Work. Sloan Management Rev. 47(3) 56–63. Scott, S.V., G. Walsham. 2005. Reconceptualizing and Managing Reputation Risk in the Knowledge Economy: Toward Reputable Action. Organ. Sci. 16(3) 308-322. Serva, M. A., M.A. Fuller, R.C. Mayer. 2005. The reciprocal nature of trust: A longitudinal study of interacting teams. J. Organ. Behavior 26 625–648 Smith, A. 2010. Mobile Access 2010. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Mobile-Access-2010.aspx. Sweeney, L. 2010. Designing a trustworthy nationwide health information network promises Americans privacy and utility, rather than falsely choosing between privacy or utility. Testimony to Congress. Staples, D.S. J.Webster. 2008. Exploring the Effects of Trust, Task Interdependence and Virtualness on Knowledge Sharing in Teams. Inform. Systems J. 18 617-640. Te’eni, D. 2001. A cognitive-affective model of organizational communication for designing IT. MIS Quart. Rev. 25(2) 251–312. van Dijck, J. 2009. Users like you? Theorizing Agency in User-Generated Content. Media, Culture, Soc. 31 (1) 4158. von Hippel, E., G. von Krogh. 2003. Open source software and the private collective innovation model: Issues for organization science. Organ. Sci. 14 (2)209-223. Walther, J.B., B. van Der Heide, L.M. Hamel, H.C. Shulman. 2009. Self-Generated Versus Other-Generated Statements and Impressions in Computer-Mediated Communication: A test of warranting theory using Facebook. Comm. Res. 36(2)229–253. Walther, J. B. 2007. Selective self-presentation in computer-mediated communication: Hyperpersonal dimensions of technology, language, and cognition. Comput. in Human Behavior 23 2538-2557. Wasko, M., S. Faraj, 2005. Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. MIS Quart. 29(1) 35-58. Wasko, M., S. Faraj, R.Teigland. 2004. Collective Action and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. J. Assoc. for Inform.Systems 5 (11-12).493-513. 20 21 Weber, J.M., D. Malhotra, J.K. Murnighan. 2005. Normal Acts of Irrational Trust: Motivated Attributions and the Trust Development Process. Res. in Organ. Behavior 26 75-101. Wright, R., S. Chakraborty, A. Basoglu, K. Marett. 2010. Where Did They Go Right? Understanding the Deception in Phishing Communications. Group Decis. Negot. 19 391-416. Wright, R.T., K. Marett. 2010. The Influence of Experiential and Dispositional Factors in Phishing: An Empirical Investigation of the Deceived. J. Management Inform. Systems, 27 (1) 273-303. Zahedi, F.M., J. Song. 2008. Dynamics of trust revision: Using health infomediaries. J. Management Inform. Systems 24( 4) 225-248. 21