Granovetter`s weak tie theory

advertisement

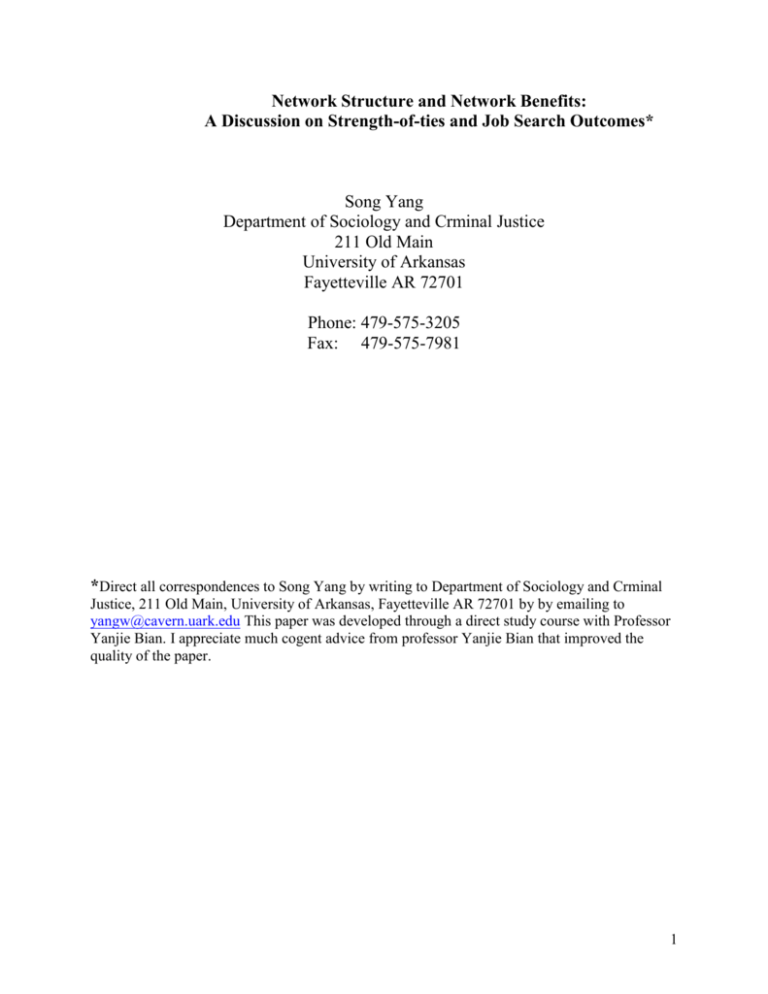

Network Structure and Network Benefits: A Discussion on Strength-of-ties and Job Search Outcomes* Song Yang Department of Sociology and Crminal Justice 211 Old Main University of Arkansas Fayetteville AR 72701 Phone: 479-575-3205 Fax: 479-575-7981 *Direct all correspondences to Song Yang by writing to Department of Sociology and Crminal Justice, 211 Old Main, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville AR 72701 by by emailing to yangw@cavern.uark.edu This paper was developed through a direct study course with Professor Yanjie Bian. I appreciate much cogent advice from professor Yanjie Bian that improved the quality of the paper. 1 Network Structure and Network Benefits: A discussion on strength-of-ties and job search outcomes I review four prominent studies on network structure and job search outcomes. I find that Lin’s social resource theory has a missing link between establishing ties with contacts and job search outcomes. To fill the gap, I assert that social actor mobilize their contacts’ resources by eliciting crucial information and influence in favor of their job search processes. I also identify that separating information benefit from influence benefit is the key point in this line of work. Empirical test is imperative to discover which benefits are more significant in explaining job search outcomes under a certain social institution. Finally, I produce seven testable hypotheses in summarizing the discussions. Granovetter's weak tie theory In an effort to find the association between network structure and job search outcomes, Granovetter (1973) found a troubling result that the respondents in his studies always found jobs through distance personal contacts rather than close associates. Ironically, this troubling result eventually leads him to the widely cited argument "The Strength of Weak Ties (1973)" and the book, Getting a Job (1995). I review Granovetter’s theory in detail in the following paragraphs. Granovetter starts his discussion by attacking new classical labor market theory. In the classical conception, labor supply and demand operate to establish equilibrium, at which point the price of labor clears the labor market. Granovetter asserts that a number of factors work against the perfect labor market model. Social and institutional pressures exert constraints on the free movement of labor. On top of these factors, job seekers and employers receive different 2 amount of information, which either facilitate or constraint the job searching or head hunting processes. Due to the time and resource constraint, job seekers use a number of methods to maximize information for current job openings. Granovetter’s empirical studies on professional, technical, and managerial employees (PTM) indicate that job seekers use three methods to find jobs: formal means, personal contacts, and direct applications. Those using personal contacts obtain information of high quality than people using other methods. Personal contacts offer more than a simple job description. Job seekers may learn potential opportunities for their personal development, or if the company is moving forward or is in stagnant ( Granovetter 1995: 13). The basic observation is that personal contacts, as opposed to direct application, and formal methods, gives job seekers information advantage in an imperfect labor market. Those information advantages contribute to such job searching outcomes as high income, high job prestige, and high job satisfaction. Granovetter’s crucial finding is that those personal contacts generating information advantage are not close ties such as family or kinship connections but distant relations such as chatting partners in a sport bar. Granovetter thus defines personal contacts as those individuals acquainted with the respondents in some context unrelated to a search for job information, but later on either provide information or recommend the respondents to a position (Granovetter 1995: 11). Then why those personal contacts rather than family members or close friends account for job seeking advantage? Granovetter’s answer is that personal contacts lead the respondents to a pool of non-redundant information, whereas close allies provide information already known to the respondents. For job seekers, non-redundant information enlarges a pool of 3 career opportunities, whereas redundant information restrict their attentions to a limited set of openings, blocking the avenues leading to better job offers. The issue of information redundancy/non-redundancy is essential to Granovetter’s weak tie argument, which explains the superiority of weak ties over strong ties in producing favorable job search outcomes. Weak tie theory inspired a number of theoretical and empirical studies. Three researchers are quite prominent in this line of work: Lin’s (1982, 1990) social resource theory, Burt’s (1992) structural hole theory, and Bian’s (1997) strong tie argument. To Lin, social structure is conduit to such resources as information, social status, and a number of rewarding opportunities. Burt proposes structure concept to account for information and control benefits. Bian brings strong ties back in by contextualizing job search process in Chinese society. I discuss each of the literatures in the following sections. Lin’s social structure and social action theory Lin’s social structure theory is built upon three assumptions for macro social structure and two assumptions for micro behavior. For macro structure, Lin (1990) assumes that 1, social structures are hierarchical; 2, hierarchical resources tend to be congruent and transferable. For example, an occupant in a good command of one resource dimension tends to gain control of resources in other dimensions; 3, the theory assumes that hierarchical social structures are pyramidal: the upper levels having fewer occupants than the bottom levels. For micro structure, Lin assumes that 1, individuals use homophilous interactions, the interactions taking place among individuals at similar hierarchical levels, to maintain existing resources; 2, individuals use heterophilous interactions, interactions taking place among individuals at dissimilar hierarchical levels, to gain additional resources. Lin contends that homophilous interactions capture a decent 4 amount of intellectual attentions, whereas studies on heterophilous interactions are scarce. Lin stresses that heterophilous interactions explain a substantial amount of social mobility and motivations in most societies. Based on those assumptions, Lin (1990) proposes three hypotheses: the social resources hypothesis, the strength-of-position hypothesis, and the strength-of-ties hypothesis. Elaborating all the hypotheses goes beyond the scope of my discussion. I only review strength-of-ties thesis. Simply stated, the hypothesis predicts a positive relationship between the use of weak tie and connecting to social contacts with better resources expressed as high social status, and power. Lin reasons that homophilous interactions occur among people with strong ties due to that 1, the purposes of the interactions are expressive and 2, people engaging in homophilous interactions have similar social status. In contrast, heterophilous interactions occur among people with weak ties because 1, people engage in the interactions for instrumental purposes, and 2, those people have different social status. Lin contends that the initiators for heterophilous interactions are always those down in a hierarchical order. They strive to obtain additional resources by building a bridge with those high in a hierarchical order. Lin and his associates found empirical support for the strength-of-ties hypothesis in labor market studies. The respondents’ occupational prestige is contingent on their contacts’ occupational prestige leading to the jobs. Individuals using weak ties are more likely to connect to contacts with better resources than those using strong ties (Lin 1982; Lin, Ensel, and Vaughn 1981). But Lin’s weak tie hypothesis and Granovetter’s weak tie theory have two fundamental differences. First, Lin argues that heterogeneous interaction explains resource advantage. Social actors build up ties with contacts in high social hierarchy in an effort to mobilize the better resources. Those cross-strata ties are likely to be weak rather than strong. Granovetter asserts 5 that weak ties benefit job seekers by providing non-redundant information. Second, Lin did not spell out the mechanism that social actors mobilize the social resources. Simply connecting to those contacts is not sufficient for social actors to obtain those resources. What missing from Lin’s discussion is how social actors use the resources after they are connected to their contacts high in rank. Burt’s structure hole theory fills in the gap elaborating the process linking social network positions to resource advantage. While Lin concentrates on whom you can reach through social structures. Burt underscores how network positions bring about advantage to social actors. I discuss Burt’s structural hole theory in detail in the following paragraphs. Burt’s structure hole theory Burt (1992) contends that information advantage expresses in three forms: information access, timing of information, and referrals. Information access emphasizes receiving information and knowing who can use it. Timing of information refers to receiving information earlier than others. Personal referral is defined as that actors’ personal contacts exert influence facilitating the actors’ job searches. What kind of network structures is conducive to those information advantages. Burt’s answer is structural hole, defined as a relationship of non-redundancy between two contacts. Burt identifies two types redundant relationships (indicating absence of structural holes): redundancy by cohesion, and redundancy by structural equivalence. Cohesion redundancy refers to that two actors being connected by strong relationship. Structural equivalent redundancy is that social actors have the same (or the same set of ) social contacts. Either cohesion redundancy or structural equivalent redundancy offers redundant information. Actors tying to two strong connected persons tend to receive the same information from them since they are sharing a 6 similar set of information. Actors connecting to structural equivalent players receive the same information circulating inside of each structural equivalent cluster. In contrast, each nonredundant cohesion or non-redundant structural equivalence indicates the presence of structural hole, or non-redundant information. Each disconnected social actors are likely to be an independent source of information. The time and resources restrict social actors’ connections to a limited set of contacts. Within this constraint, identifying disconnected actors and spanning over structural holes is critical for social actors to maximize information. Identifying structural holes and connecting to disconnected actors improve what Burt called network efficiency, whereas identifying the leaders in each disconnected groups and establishing ties with the group leaders increase network effectiveness. Network efficiency and network effectiveness not only expose actors to diverse sources of information but also make actors the first one to see new opportunities and impending disasters. Because the actors are the only avenues linking the disconnected players, the actors are likely to capture emerging opportunities largely invisible to other disconnected players. In sum, network efficiency and effectiveness get social actors to valuable information at the time before anybody else dig it out. In addition to information benefits, Burt asserts that structural hole also embraces control benefit for those who can take advantage of the hole. Social actors can play two disconnected players one off another in an effort to negotiate a favorable term for themselves. Real life example can be that a sociology graduate receives several job offers. Not only that she has more options but also can play the employers one off another to produce a best contract for herself. Burt asserts that information benefit and control benefit are mutually reinforced. Those capable of obtaining information at right time are likely to elicit control benefits from that information. 7 It is one thing that one learns job openings in one’s area when one is far away from graduation. It is another to learn several job offers in one’s area when one actively conducts job search. Burt and Granovetter are disagreed on what explains information advantage, nonredundant information. To Burt, structural hole produces non-redundant information, whereas those ties spanning structural holes are likely to be weak. In other word, structural hole is the source for non-redundant information. Weak ties simply indicate the presence of structural holes. To Granovetter, weak tie per se carry social actors to a pool of non-redundant information. Empirical tests provide mixed findings for the weak-tie argument. Marsden and Hurlbert (1988) did not find empirical support for weak tie theory. Watanabe (1987) and Bian (1997) found the opposite side of story: strong ties rather than weak ties account for favorable job search outcomes in Japanese and Chinese society respectively. Why this is so? How those findings improve the strength-of-tie thesis in general? Below I review Bian’s strong tie assertion in detail. Bian’s strong tie argument Bian (1997) extends Granovetter’s theory in three directions. First, Bian distinguishes influence and information, arguing that while weak tie is useful in spreading information, strong tie is used to elicit influence to facilitate job placement. Second, Bian introduces indirect ties, the ties connecting job seekers to their ultimate helpers through intermediaries, which is a key insight derived from Granovetter’s weak tie discussion. Third, Bian put job search process in Chinese labor market context, finding that influence rather than information explains succeed in job placement and replacement. 8 Why weak tie assertion does not hold true in Chinese labor market. Bian states that Chinese central planning of labor resources prohibits the use of contacts in labor assignment. Job seekers and their ultimate helpers need considerable personal trust to engage in labor replacement transaction. Weak ties do not embrace high-level trust and strong obligations. Strong ties do. Consequently, Chinese job seekers and job helpers have strong ties, normally accessed through family connections. Moreover Chinese job helpers provide more than job information. They exert direct influence on hiring process in favor of job seekers, which is critical for finding new jobs. Using a sample of 1,008 cases of 1988 survey in Tianjin, China, Bian (1997) discovered that 1, for direct relations, job seekers and job helpers are connected through strong ties, and 2, for indirect relations, job seekers and job helpers are both strongly connected to the intermediaries. Bian’s research strongly suggests that information and influence need to be disentangled in future strength-of-tie studies. Weak tie assertion, be it structural hole, heterogeneous interaction, or weak tie per se, stresses how such high quality resources as nonredundant information, and high occupational prestige facilitate job search and promotion, whereas strong tie argument underscores how interpersonal trust, obligation, and direct influence play a role in job placement. I contend that which argument is more prominent in explaining the effect of strength-of-tie on individual actions is contingent on social context, a plausible explanation to reconcile tie strength disagreement. In western societies where tie strength does not make a difference in eliciting influence on hiring process, the non-redundant information become crucial benefits to job seekers, whereas in Chinese or Japanese societies where interpersonal trust and obligation are always needed to elicit influence on job placement, strong ties embracing those trusts and obligations are significant in obtaining jobs. 9 In previous sections, I review major theoretical and empirical studies on social network and job search literature. From the review, I identify several empirical questions. First, How tie strength is related to information versus influence? Do weak tie-information, and strong tieinfluence associations hold true? Second, what is the mechanism supporting Lin’s discovery that one’s job prestige is conditional on her/his contacts’ status, who leads one to the job? How social actors mobilize the better resources obtained via weak ties with their social contacts high in hierarchical order? Third, Does non-redundant information or direct influence exert significant effect on job search process? Which one accounts for favorable job search outcomes? Fourth, Speaking to Burt’s structural hole theory, can structural hole replace weak tie in explaining non-redundant information? In other word, will structural hole affect both tie strength and non-redundant information, thus making the association between weak tie and nonredundant information spurious? I construct a conceptual model to address those issues in the following paragraphs. Discussion and implication The essence for Granovetter’s weak tie assertion is that weak tie generates non-redundant information. Bian’s empirical studies suggest that strong tie elicit influence, which plays a significant role in Chinese labor market. I produce two hypotheses based on their discussions. H1. Individuals using weak ties are more likely to have information benefits from their contacts than those not using weak ties. H2. Individuals using strong ties are more likely to have favorable influence from their contacts than those not using strong ties. 10 Considering hierarchical social structure as a conduit, Lin argues that social actors mobilize social resources by getting to know those controlling the resources, which suggests that whom you know is more important than how you know in job search process. My third hypothesis speaks to this school of thought. H3. Individuals using weak ties are more likely to know their contacts in relatively higher social status than those not using weak ties. Lin , however, did not elaborate the mobilizing process, in which social actors use the resources controlled by their contacts. I assert that social actors persuade their contacts either to exert influence or to provide crucial information in favor of their actions. Specifically in job search process, job seekers may ask for favorable comments, recommendation, and critical information beyond simple description of openings. I produce the following hypothesis in extending Lin’s contention. H4. Job seekers’ social contacts are likely to exert influence or to supply information in favor of the job seekers. Which type of favor the contacts offer depends on which one is more important in facilitating job search. I make a contingent argument on the association between information benefits/influence benefits and job search outcomes. That which benefit explains job search outcomes depends upon social institutional context. Chinese labor market operated on a rigid central planning mechanism renders high trust and obligation between job seekers and job helpers, which were normally embraced in strong ties. In American society where high trust and obligation is not sufficient condition leading to exchange of favors, weak tie become prominent in job search by providing information of high quality (Granovetter 1995:11). 11 H5. In Chinese labor market, individuals obtaining influence are more likely to gain favorable job search outcomes expressed as high efficiency (length of staying in labor market, the short the length, the higher the efficiency), and high effectivenss (high income, prestige, and job satisfaction). Burt challenges Granovetter’s weak tie theory by proposing a structural hole concept to explain network advantages such as information and control benefits. In line with Burt’s assertion, I speculate that structural hole, which is indicated by small number of peers (Burt 1997), is the source of information benefits. Social ties bridging over structural holes are likely to be weak rather than strong. H6. Those social ties bridging over individuals with small number of peers tend to be weak, whereas social ties connecting individuals with large number of peers tend to be strong. H7. Individuals with small number of peers, which indicates presence of structural hole, are more likely to obtain information benefits than those with large number of peers. Diagram 1 displays the causal path linking different theories. The key point of this paper is separation of information benefits and influence benefits. By doing so, I reconcile Granovetter and Bian’s disagreement, enrich Lin’s social resource theory, and speak to Burt ‘s structural hole argument. As researchers converge in underscoring information and influence as underlying mechanism facilitating job search, empirical test of the area is scarce. Future researchers in network benefits, and job search literature should address this gray area. 12 References: Bian, Yanjie. 1997. “Bringing Strong Ties Back In: Indirect Ties, Network Bridges, and Job Searches in China.” American Sociological Review 62:366-385. Burt, Ronald. 1992. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press. _________. 1997. “The Contingent Value of Social Capital.” Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 339-365. Granovetter, Mark. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78:136080. _________. 1995. Getting a Job. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Lin, Nan. 1982. “Social Resources and Instrumental Action.” Pp. 131-47 in Social Structure and Network Analysis. edited by P. Marsden and N. Lin. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. _________. 1990. “Social Resources and Social Mobility: A Structural Theory of Status Attainment.” Pp. 247-71 in Social Mobility and Social Structure, edited by R. Breiger. New York: Cambridge University Press. Lin, Nan, Walter M. Ensel, and John C. Vaughn. 1981. “Social Resources and Strength of Ties: Structural Factors in Occupational Status Attainment.” American Sociological Review 46:393405. Marsden, Peter V. and Jeanne S. Hurlbert. 1988. “Social Resources and Mobility Outcomes: A Replication and Extension.” Social Forces 66:1038-59. Watanabe, Shin. 1987. “Job-Searching: A Comparative Study of Male Employment Relations in the United States and Japan.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Sociology, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA. 13 Structural hole measured by the number of peers (Small number of peers indicates presence of structural holes, where large number means absence of structural hole). H6 1992) (Burt H7 Information versus influence. (Granovetter 1995, Bian 1997, and Burt 1992) H1, H2 Strength-of-ties (weak ties versus strong ties) (Granovetter 1995, Nan 1990, Burt 1992, Bian 1997) H4 H3 Social Resources (Whom you know). (Nan 1990) H5 Job search outcomes measured by effectiveness and efficiency. Efficiency refers to length of search. Effectiveness indicates how well the jobs are (occupational prestige, income, and job satisfaction). (Granovetter 1995, Nan 1990, Burt 1992, Bian 1997). Diagram 1. Path Analysis of Strength-of-ties and Job Search Outcomes 14