Summary of Legislation and statutory interpretation

advertisement

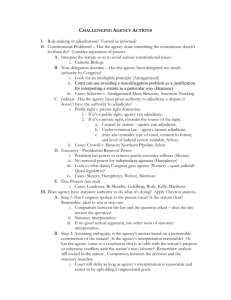

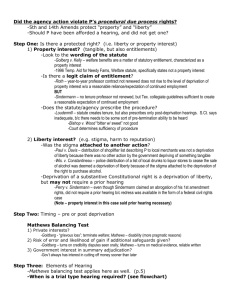

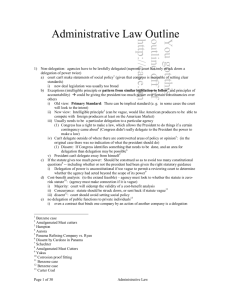

I. Basic doctrines of statutory interpretation A. Canons both linguistic and substantive 1. 5 linguistic Canons a. Expressio Unis—expression of one to the exclusion of others (specific list and it’s only the list) b. Ejusdem Generis—of the same type, look at catch all at end of list based on list members c. Against Redundancy—each word has individual meaning d. “Noscitur a sociis” –a word is known by the company it keeps e. Consistent Usage: Within Statute—Gustafson Among Statutes—WV Hospital 2. 2 Substantive Canons a. Lenity—when criminal statute ambiguous, interpret in favor of defendant (McBoyle) b. Avoiding constitutional questions (NLRB v. Catholic Bishops) i. Doctrine of severability—when a statute is unconstitutional in some applications, it’s only held invalid as to the unconstitutional aspects (subject to legislative intent). B. Legislative History 1. Hierarchy a. Committee Reports > Sponsor’s Statements > Floor debate >Hearings b. Ratification--Statute, then judicial decision interpreting, then reenactment of statute with no change means Congress upholds interpretation c. Acquiescence--Statute, interpret, congressional silence after taken to approve interp i. Textualists say no reason to find approval, Purposivists say failure to act sign of intent d. Rejected Proposal--Congress rejects a proposed statute means can’t have meant that b/c didn’t approve i. Textualists—no legal event at all, Purposivists—evidence that didn’t intend 2. How judges use LH a. Intentionalist/Purposivist—use LH all the time (American Trucking regime) b. Textualists—originally don’t use LH, could however say LH helps interpret text (Breyer move) c. Plain-meaning rule—no LH when text is clear, use LH when text ambiguous i. Conceptual critique—if LH useful when ambiguous why not also when determining if ambiguous ii. Pragmatic critique—rule tends to break down b/c there are incentives to use LH in any case 3. Intentionalist Delegation Model—reasons for LH a. Congressmen are agents of the majority with delegated authority and have incentives to remain true to majority wishes b. Using LH makes it more likely for LH to be accurate 4. Textualist Critique of LH a. Text is the law (Historically 2nd) based on Article 1 Section 7 i. Nobody denies it after Breyer’s move saying text is law but use LH to figure out what it says ii. Plenty of sources that judges consider that aren’t the law—canons, dictionaries, that would also fall under this objection b. No legislative self-delegation (Historically 3rd) refining of “text is law” i. Using committee report is equivalent to delegation of lawmaking power to a committee. ii. Has same problems as ‘text is law’ b/c there is no formal delegation of law-making power. iii. Formally the Breyer point holds that they’re just using committee report as reference to figure out what it means, not viewing it as a delegation of power. c. Reliability (Historically 1st)—Most persuasive version according to Vermuele. i. Empirical claim that all premises of the intentionalist delegation model might be correct in principle but that’s not in fact what happens b/c there is sufficient “agency slack” in each link of the chain of delegation so at the end the agent is running around non-representative of the majority. ii. If judges look at LH it creates additional incentives for special interests to try to manipulate it so very act of using LH ensures LH is unreliable (opposite of ID model argument for LH) II. Major “isms” A. Intentionalism-- get the goals of the enactors (if asked congress in x case, would have said. . .) 1. Dissent in TVA v. Hill (Congress would not have intended this absurd result) 2. Riggs v. Palmer (Legislature couldn’t have intended murderer to inherit) 3. Holy Trinity (absurd result) B. Purposivism-- get purposes, higher generality than intent 1. Stevens’ in WV Hospital (purpose was to undo prior case and compensate for cost) 2. Absurdity doctrine and its broader and narrower versions—necessary to purposivism and intenationalism a. Kirby—narrow version “all mankind would unite in objecting to application” b. Public Citizen—broader b/c dissent over whether or not absurd C. Textualism—text is law, ordinary meaning of words applies 1. Rules a. Ordinary meaning of text (connotation over denotation) vs. literal meaning or terms of art b. In statutory context look at other sections and other statutes vs. legislative history c. Argument about what type of context should be examined, not whether or not to use context 2. Main types of meaning/Use of dictionaries a. Ordinary or colloquial meaning ( Nix--tomato) b. Presumption ordinary meaning applies unless reason to think otherwise c. Literal meaning or denotation (Smith—“use a gun”) d. Specialized or “term of art” (Moskal—falsely made) 3. Rationales for textualism a. Article I section 7—constitutionally specified procedures for lawmaking b. Text is the law—that’s what the legislature has voted on, the vote is legally effective regardless of legislative intent c. Text is the best evidence of purpose/intent (it doesn’t mean only) d. Multiple purposes/compromise e. No purposes—statutes emerge from intersection aims of multiple actors, could be the case that the statute that emerges isn’t what any part would have unilaterally chosen so there is no collective purpose behind the legislation. 4. Judicial Role a. Legislature has power to change laws, judges don’t b. Ex ante incentives D. Sources by which one might pursue those isms 1. It is possible to be in one camp and use each of the tools, ex. textualist who uses LH to figure out meaning, purposivist who never looks at LH E. Judicial Capacity III. Equitable Interpretation of Statutes A. Posner in Marshall looks at broad purpose behind statute and says dosage is best determination B. Think about justice or “rules and standards”—do we look at the desirability, costs and benefits of our interpretive methods on a case by case basis or in a more wholesale way. Administrative Law I. Non-delegation Doctrine--congress can’t delegate what it doesn’t have A. Need an “Intelligible principle”—JW Hampton (1928) B. Breadth—Schechter (1935) C. Sliding Scale (broader the statute, most defined an IP needed) Whitman (2001) II. Power to Dismiss/Direct A. Congress can only dismiss by impeachment (Bowsher) B. President can dismiss purely executive (Myers) although made independent by congress (Morrison) but independent w/ quasi-judicial functions only for cause (Humphreys) III. Procedure A. Constitutional Due Process challenge to procedure (Bi-metallic, Londoner, Chenery) 1. Bi-metallic v. Londoner—mostly agency gets to decide which territory they’re in a. Rule-making—legislative process is due process and need no more b. Adjudication—may need an oral hearing, but not always i. Depends on generality/numbers of the people affected 2. Chenery I—AA has to give reason for decision in same proceeding where it makes decision, can’t use posthoc rationalization 3. Chenery II—AA can chose whether to proceed by general rule or ad hoc adjudication a. Exception: retroactive effect requires weighing benefits of action v. harms of retroactivity B. APA Requirements 1. Rule-making versus adjudication—distinction same as constitutional (specific/adjudication, general/rule) 2. When, if ever, does an agency have to engage in rule-making? a. Chenery II—choice b/w rule-making and adjudication within the discretion of the agency with exception for retroactivity. 3. When does the agency have to engage in adjudication? a. Agencies don’t ever really have to adjudicate instead of making rules (Texaco--companies, Heckler-individuals) i. Allows for Texaco two-step where T1 rulemaking limits scope of T2 enforcement adjudication Agency hasn’t denied challenge, it’s just channeled at the time of rule creation and then it can’t be re-litigated. b. Contingent upon organic statute allowing agency both procedures (presumption is that both are allowed National Petroleum 4. Adjudication Procedures required by APA a. Formal 554 (a), 556-7—defer to agency’s reasonable interp. of own organic statute as long as doesn’t say “on record” (Seacoast and Dominion) b. Informal i. 555 (Ancillary Matters)—allowed to bring a lawyer, agency must give brief grounds for denial of application or petition. ii. 95% of what agencies do is informal and subject to no procedural restraints 5. Rulemaking Procedures required by APA a. Formal 553(c)—trigged by “after hearing on the record” in organic statute (Florida East Coast) i. 556 (d) says even then agency can stipulate to written proceedings if no party will be prejudiced (although parties always claim prejudice) ii. Court can still interpret organic statute to require formal rulemaking even if APA isn’t triggered b. Informal or “notice and comment” rulemaking--Agency has to publish notice of proposed rule, allow comments, and issue final regulation with explanation 553 i. Attempts to increase procedural formality of notice and comment beyond APA requirements Hybrid Rulemaking—outlawed by Vermont Yankee Paper Hearing Requirement 553 1. Require elaborate explanations for final rules 2. Disclosure of scientific data or studies if part of rationale (Nova Scotia) 3. Logical Outgrowth requirement (Weyerhauser) Hard Look Review 706—no matter what procedural format can give hard look to agency’s reasoning c. Excepted—553 (a) 1-2, 553 (b) A-B means don’t have to follow requirements at all i. Interpretive rules—American Mining Test if any of 4, not interpretive and needs notice and comment—1. w/out rule no basis for enforcement, 2. published in Federal Code of Regulations 3. explicitly invoked legislative authority 4. amends prior legislative rule ii. General statements of policy—needs notice and comment if binding (must allow discretion) or has present affect (Community Nutrition & US Telephone) iii. Rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice—notice and comment if document intended to and/or does change in a binding way the first order conduct of parties iv. Good Cause C. Organic Statutes--can impose procedural requirements on agencies beyond the APA. 1. Organic statute can trigger APA formality with ‘hearing on the record’ 2. Organic statute can also directly impose procedural requirements if says “hearing” and LH says that it means oral interpretation, thus it would be acceptable to interpret the statute that way (opposite of way court interprets in Florida East Coast) D. Agency Past Procedures 1. Arizona Grocery—if sequence is a rule followed by order in adjudication on the order the agency can’t change the underlying rule. 2. AZ Grocery is a default rule read into organic statutes unless specifically rebutted IV.Estoppel--SCOTUS never upholds admin law estoppel claims against gov’t. At lower court might under egregious circumstances of intentional misconduct by agents. (Schwieker & OPM) V. Bias—Fantasy is an adjudicator who is neutral expert with high level of activity, not really possible because perfectly neutral decision makers in the real world are passive A. APA—separate staff for investigation/prosecution and decisionmaking (Wong Yang Sung) 1. Doesn’t apply to top-level and only applies to formal adjudication 2. Not per se unconstitutional in non-APA cases (Larkin) B. Pecuniary interest (Gibson)—applies in rulemaking and adjudication C. Judge cannot have been target of personal criticism by a party—adjudication, possibly in rulemaking D. Prejudged legal, policy issues, facts--adjudication (ANA v. FTC) NOT rulemaking (Cinderella) VI. Review of Law: Skidmore, Chevron and Deference A. Skidmore—only give epistemic deference to agency rationales on basis of expertise, look at thoroughness, consistency, etc. 1. Is the agency’s interpretation reasonable (f yes, defer to agency) B. Rationales for Chevron 1. Expertise—also rationale for Skidmore so not as distinctive an argument 2. Implied delegation—Problem with this idea is that character of the rationale, nothing in the USC shows an implication that gaps are delegated to agencies instead of courts 3. Political accountability—agencies are politically accountable through Pres. oversight and courts aren’t C. Step Zero—question of whether we’re in the Chevron framework at all. 1. Type of statute—agencies only get deference on their own organic statute 2. Mead—decides whether to apply Chevron or Skidmore a. In Skidmore deference unless affirmative showing of congressional intent to delegate power to make rules with force and effect of law b. “spongy” totality of circumstances test i. Heightened procedure proxy for congressional intent but neither necessary nor sufficient ii. Also look at organic statute, level of decision-maker in agency D. Step One -Has Congress has spoken to the precise question at issue? Gap or ambiguity 1. Use traditional tools of statutory interpretation (Cardoza Fonseca) 2. Breyer view—look at whether Congress would have wanted to delegate to agency (Sweet Home footnote) 3. Major Questions Canon-- Congress assumed not to have delegated to agencies questions of far reaching economic and political significance unless specifically state it (MCI & Brown) a. Non-delegation canon can work for or against Chevron (Mass v. EPA) b. Scope of agency action can help determine whether a “major question” (Mass v. EPA) E. Step Two—is the agency’s interpretation reasonable? 1. Agency can switch ideas within reasonable range, as long as court hasn’t said there is only one reading (Brand X) and presumption is “permissible” court interp rather than “only” 2. Agency can use cost-benefit analysis unless clearly forbidden by organic statute (Entergy) VII. Arbitrary and capricious—whether Agency has given right reasons, not whether it has the authority A. Consider all and only the relevant factors (Overton Park) 1. Must have record showing what factors considered, complied by agency (Pension Benefit) a. “Relevant factors” come from organic statute (Pesticides) 2. Must consider “reasonable policy alternatives” (State Farm—airbag only standard) a. “heart of ossification” b/c agency has to guess what factors court will consider reasonable B. No clear error of judgment (example of court’s interp of study in State Farm) 1. Change in policy, no per se obligation to give a reason for change (Fox) as long as a. Policy must be permissible under statute (Chevron) b. Give good reason for policy but doesn’t have to show it’s better than the old one i. Must address any reliance interest under old policy ii. If new policy is based on a factual finding underlying the old policy agency has to explain that C. Refusals to make rules are just as reviewable as rules (Mass v. EPA)