What is the UDL Implementation process?

advertisement

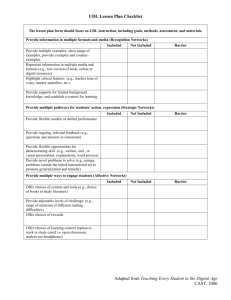

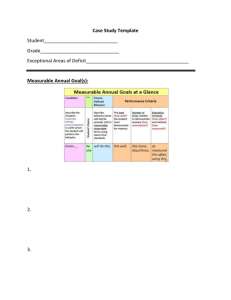

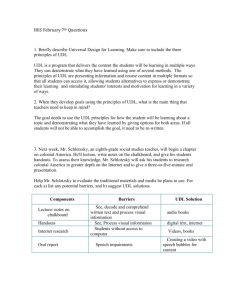

UDL Implementation: A Tale of Four Districts Introduction UDL Implementation: A Tale of Four Districts is the story of four school districts taking the journey into the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) implementation process. Baltimore County Public Schools in Maryland, Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation in Indiana, Cecil County Public Schools in Maryland and Chelmsford Public Schools in Massachusetts participated in the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded project to explore and pilot processes and tools developed to support UDL Implementation within their own unique districts. The story is told primarily through the voices of the dedicated educator leaders from these districts and the UDL facilitators who supported them. During the one-year grant, the districts worked with CAST, Inc. to develop and implement an effective and sustainable district plan to support the integration of Universal Design for Learning. What is Universal Design for Learning? For those who are unfamiliar with Universal Design for Learning (UDL), it is a set of principles and guidelines that serve as a framework for curriculum design and educational decision-making. These principles provide a blueprint for creating instructional goals, methods, materials, and assessments that work—not a single, one-size-fits-all solution but rather flexible approaches that can be customized and adjusted to address the variability of all learners. To learn more about Universal Design for Learning visit the National Center on UDL http://www.udlcenter.org/ or watch this video: UDL at a Glance. To access the full UDL Guidelines as shown in this graphic, see http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines. What is the UDL Implementation process? UDL implementation is a process of change that tends to occur in a recursive, continuously improving cycle of learning and progressing. The process is designed in a UDL way, uniquely customized to support change in each district. Researchers at CAST believed that by integrating systems change research with the UDL principles they could provide school staff with a customized, cascading, series of professional learning opportunities, professional coaching, facilitation, supports, resources and tools needed to assist districts throughout the UDL implementation. This is an important distinction that makes UDL implementation different from other initiatives that attempt to hold participants to a specific, regimented implementation approach. The UDL implementation process isn’t a set of protocols that everyone does in exactly the same way. The four participating districts were as varied and complex as the students in their classrooms, so each district’s approach to UDL implementation was different. Each district identified the structures within their system and anticipated different paths and plans for scaffolds and supports that would meet the needs of their own unique system to move forward toward scaling and optimizing UDL implementation. Even though five phases of UDL implementation have been identified, it is also recognized that each school, district or higher education institution will approach the UDL implementation process in a unique manner. The five phases within an integrated dynamic process of UDL implementation, adapted from Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, and Wallace (2005), are: (1) Explore, (2) Prepare, (3) Integrate, (4) Scale, and (5) Optimize. These are not rigid stages but instead are fluid and recursive in nature. The UDL Principles are purposefully infused throughout the process. For example, each phase includes three focused goal areas aligned with the three UDL principles. Implementation phases may exist as discretely separate, sequential periods of focus for some schools or districts or they may overlap or repeat in an iterative manner. The graphic below offers another way of thinking about the UDL implementation process that highlights its iterative, continuously improving aspects. UDL Implementation Process Diagram The Plan Each district started at a different place in the process, one had been exploring, planning and integrating UDL practices for several years while another was just starting to explore the possibilities of using UDL as a framework to guide curriculum development. Yet the goal for all four districts was to develop and implement an effective and sustainable plan for integrating UDL systemically into its district. One of the first things any district needs to do when investigating UDL as a framework is to consider what their needs are. Then, they determine if using the UDL framework can address those needs. The work included building block activities such as, identifying district goals that align with UDL Implementation, assessing knowledge, practice and beliefs, working with a UDL facilitator to develop Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) that would support teachers’ use of the UDL instructional practices, collaboration in planning curriculum and instruction, and incorporating professional coaching specifically related to applying UDL to instructional strategies. CAST developed tools and services to support UDL Implementation at the district level including: professional development, interest and self-assessment surveys, technical assistance, a UDL Implementation Strategy Guide and a UDL facilitator’s guide. Enabling resources included a web-based tool, UDL Exchange, which assists educators in applying UDL to lesson planning and supports sharing of lesson plans, resources and collections of information. Critical Elements of UDL Implementation Through our work with these four districts, we learned that the following elements are critically important to successful implementation of the UDL framework as a process of change: a top-down and bottom-up approach encourages meaningful systemic change in both decisionmaking and classroom practices customized decision-making tools inform school and district leadership UDL facilitators guide and help to sustain key systems level changes a collaborative team approach builds educator expertise in lesson planning and instruction on-line, virtual and blended tools and resources offer just-in-time learning support Many successful strategies were apparent across the four districts, including: UDL is the district-wide framework, is embraced by stakeholders at all levels, and helps inform decisions. It is not viewed as just another initiative. Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), led by motivated teachers or coaches, are supported by school and district administration and provided the time and resources to build UDL expertise, share their lessons and reflect on their work together. An embedded UDL Facilitator supports and mentors educators, defines resources, and guides the building of UDL expertise in the district community. UDL is modeled at all levels including during educator professional development. Classroom teachers form a solid foundation for grassroots implementation. UDL-infused instruction focuses on the success of all students and offers an opportunity for building collaborative relationships within districts centered on learning. These stories are not intended to prescribe. Rather, they are designed to showcase the work of four districts moving through the UDL Implementation process. These stories inform others of the experiences of these four districts as they grappled with issues of school improvement, curriculum redesign and systemic change. They may also serve as an impetus for individuals at all levels to examine district or school readiness for UDL implementation While these stories and examples are limited to the districts featured, it should be noted that these districts share many of the same demographics and characteristics of districts across the country. Whether your school or district is considering UDL implementation for the first time or has been engaged in UDL implementation for a period of time, we hope these stories can serve as useful exemplars. To find out more about UDL Implementation watch UDL Implementation: A Process of Change, a part of the UDL Series. UDL Implementation: Case Stories Baltimore County Public Schools http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/baltimore Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/bartholomew Cecil County Public Schools http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/cecilcounty Chelmsford Public Schools http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/chelmsford Video Highlights PLC: Professional Learning Community http://www.udlcenter.org/resource_library/videos/udlcenter/udl#video0 Case Story Highlight 2 http://www.udlcenter.org/resource_library/videos/udlcenter/guidelines#video2 UDL Implementation: A Tale of Four Districts http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts Baltimore County Public Schools BCPS Student Demographics 26th largest school system in the U.S., 3rd largest in Maryland $1.5 billion budget, FY 2013 105,315 students (9/30/11) 54.8% minority enrollment (9/30/11) 3.8% English language learner (10/31/11) 44.8% eligible for free/reduced price meals (10/31/11) 174 schools, programs, and centers 17,000 employees, including 8,850 classroom teachers Baltimore County Public School (BCPS) district is the 26th largest school system in the U.S. It is a geographically and demographically large district that surrounds the city of Baltimore, Maryland. Like most school districts, BCPS is constantly undergoing change. During the year of the project the district hired a new superintendent who brought a different management style, background knowledge and new priorities. An important factor to consider when looking at school districts in Maryland is that the Maryland Department of Education proposed and the Maryland State Board of Education adopted regulations in June 2012 that require all local districts to use Universal Design for Learning in the development of curriculum and selection of instructional materials beginning in the 2014-2015 school year. BCPS was prepared for this legislation. Since the mid-1990s, UDL has been part of professional development provided through the Office of Assistive Technology. By collaborating with content offices and instructional technologists, the Assistive Technology (AT) team worked to demonstrate that UDL benefited all students, not only students with disabilities. Baltimore County had originally introduced UDL through the Special Education department. The framework was not embraced fully by general classroom teachers in part because it was incorrectly believed to focus on the needs of students receiving special education services. To be successfully implemented at scale, district leaders now believe that a UDL initiative should come from an identified district level need to serve all its students. Some of the activities that BCPS initiated during the Explore Phase of UDL implementation were: 1) curriculum and instruction staff participated in UDL symposiums, 2) teacher and instructional leaders participated in UDL book studies, 3) all curriculum writers received UDL professional development, 4) school administrators participated in UDL awareness activities and all principals attended a UDL workshop. The Aspiring Leaders Program, a requirement of entering the administrative pool at BCPS, added UDL professional development to its offerings as well. UDL Implementation Aligns to District Goals BCPS had a clear goal for making a change in their district. Dr. Roger Plunkett, former Assistant Superintendent, stated that the district needed to change their curriculum to align with the Common Core State Standards, move toward a 21st century curriculum and meet the needs of all learners. At this writing, the foundational curriculum documents are being rewritten to accommodate the Common Core Standards. William Burke, Director of Professional Development for the district, whose responsibilities include all curriculum development, remarks, “There is a convergence of factors that supports UDL implementation in Baltimore County right now. We are rewriting the district curriculum to adopt Common Core standards and are including UDL language and being guided by the UDL framework. It is essential to take this opportunity because it is the most authentic time to make a change to embed UDL.” He continues “Rewriting curriculum guides and lesson development guides and developing rubrics to evaluate if UDL has been embedded in the curriculum guides and lesson development will allow the district to scale UDL.” Leadership Cultivates an Environment for Continuous Improvement Two middle school principals knowledgeable about UDL were chosen to participate in the UDL Implementation Project. Sandra Reid, principal of Pine Grove Middle School, has cultivated an environment where there is an expectation for continuous for improvement. She believes that the UDL framework helps promote growth and effectiveness for both teachers and students in a seamless way because of the school’s culture. Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) Are Instrumental Principals at both schools worked with interested teachers to select and create PLCs. At one of the schools, a strong instructional leadership team helped choose the members of the PLC from different content areas. They were given time to meet during the school day, opportunities to work with UDL coaches and the UDL facilitator and they met regularly with educators from the other school. According to Burke, the development of PLCs at the schools was instrumental in supporting the implementation of UDL. Having a UDL facilitator who had previously been a consultant and teacher at BCPS was a unique and positive factor in the success of the PLCs at BCPS. She was a trusted member of the community of district leaders which allowed her to get started immediately embedding support structures and procedures for smooth communication between the district leaders, the PLCs, and UDL Implementation district team members. Another key action—professional development for curriculum content chair people – ensured that they understood the UDL principles enough to create an environment for the teachers in the PLC to experiment and take risks during the new initiative. To see a video of Billy Burke, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. A challenge for UDL Implementation involved introducing it as new initiative. It was necessary to convince educators that the district was committed to using UDL as a framework and that it was here to stay. One way that the principals worked to solve this challenge was through the work of the PLCs. The members of the PLCs were excited by their own professional growth and the growth in their students. They communicated their enthusiasm for the change to the other educators at their school. Crosscurricular teachers worked together to develop and share lessons with each other. As part of the “Something Fabulous” activity, initiated by the UDL facilitator, they created a “documentary” video to share their discovery of UDL and their professional development journey with educators throughout the district. They filmed their visits to each other’s classrooms, and their reflections on their lessons to show the process. The video is a model and instructional tool for everyone and an example of teachers driving their own professional development. “The ownership and pride in the work they are doing together and for each other has created momentum for embracing UDL in their school,” reports Nicole Norris, principal at Lansdowne Middle School. The success of the PLCs during the UDL Implementation Project stemmed from several changes that were made in their focus and make up. Previously PLCs were team meetings aggregated by content or grade level. For this project the PLCs were cross-curricular groups centered on an investigation of the UDL framework. They had an agreed-upon vision for their work and were mutually accountable for its success. Supported by UDL coaches, members of the PLCs shared lesson planning, observed each others’ classrooms and provided feedback to each other. Because the PLCs were cross-curricular they were not focused on building content level expertise, but rather on enhancing teaching practice expertise. To see a video of Nicole Norris, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Professional Development Must Be a Model of UDL Although BCPS had offered UDL professional development for many years, they felt something was holding them back from successful implementation. “We’ve been doing UDL in PD for years, but we never get past the initial phase, we never get to implementation,” states Burke. A key learning for district leadership was the realization that professional development needed to change so that it modeled the UDL principles. As Burke explains, “Our approach was wrong. We thought we were embedding it, but we were really just layering it on top of what already existed. During the Gates Implementation project the schools have learned how to embed UDL in their everyday practice and we are learning from that as a model.” To see a video of Billy Burke, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Advice from Baltimore County Public Schools: The needs of the district should form the drivers for UDL implementation. UDL needs to be embedded in the thought process at every level of decision making, from district level to student level. Create time for professional development, UDL planning and purposeful sharing. Build PLCs by giving teachers leadership roles. Research best practices for establishing and supporting PLCs. An embedded UDL coach on site to support educators is essential to successfully implementing UDL. They should be embedded in the community at each school to model, answer questions, find resources and support teachers. This was critical to the success of the PLCs. Give enough time for the UDL implementation initiative to grow. It takes time to integrate UDL thinking into instructional practice. “Let teachers grow, take baby steps and take risks.” What’s Next? Dr. Burke observes, “One of the biggest challenges will be to take the successful-built on model of coaching and intimate PLCs that were created in two schools during the UDL Implementation Project and bring the same resources to scale in one hundred and seventy-four schools.” It is a daunting task indeed, but BCPS has initiated several activities to ensure that UDL work in the district continues. BCPS has secured two new grants to support a leadership position dedicated to UDL implementation and to expand UDL PLCs into nine additional schools in their district. They plan to leverage information and resources from the UDL Implementation Project to support this effort. A survey taken by teachers indicated that finding time to share lesson plans and lessons learned was considered “most valuable.” BCPS district leaders are committed to creating PLCs and structuring the time needed to support this kind of activity. They also hope PLC members will eventually take on the UDL facilitator and leadership roles in the district. A partnership with a local university is in the works. The former state superintendent approached the district with a partnership proposition to create a lab school based on UDL as a demonstration school in conjunction with the university’s teacher preparation program. The groundwork for Baltimore County’s success is a combination of an authentic need to revise the district curriculum, successfully embedded Professional Learning Communities, informed and enthusiastic district leaders who created opportunities to support building educators’ expertise, and the commitment to fund a UDL facilitator. With this great foundation, Baltimore County is posed to continue successfully through the Integration and Scale phases of UDL Implementation. Other Case Stories in the UDL Implementation Series Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/358 Cecil County Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/359 Chelmsford Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/357 Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation (BCSC) BCSC Student Demographics 12,500 Students 83.4% White 6.7% Hispanic 4.9% Multicultural 3% Asian or Pacific Islander 1.8% African American 0.3% Native American 45% Receive free/reduced meals 13.9% Receive special education services 11% English Language Learners Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation (BCSC) is a rural school district of seventeen schools located in Columbus, Indiana, 45 miles south of Indianapolis. It is a cohesive community with very little administrative or teacher turnover. In 2003, a special education coordinator, inspired by a presentation at a conference, brought the idea of Universal Design for Learning to BCSC. Even though the district had a high percentage of their special education population integrated into regular classrooms they knew that these students were not experiencing the successes that were possible. A single pilot school dedicated to using the UDL framework was started as part of a statewide UDL initiative called the PATINS project. Today, UDL principles are applied to some degree in all of the district’s 19 schools. During the UDL Implementation project the district educators at all levels used a self-evaluation tool to help identify areas of need, resources and to find holes in the system. Agreeing to UDL as Overarching Framework Was a Crucial Step “UDL made sense for our district because the neuroscience behind UDL aligned with the district beliefs about how each student is different and learns differently,“ explains Bill Jensen, Director of Secondary Education. He continues, “For teachers implementing UDL can be daunting, especially today when they have so many pieces they must be accountable for, like the Common Core Standards and high stakes testing where there is a narrow accountability system that is strangling creativity and innovation in the classroom. Teachers ask, How will this work? Bringing in a new initiative is a huge challenge when teachers are already struggling to incorporate all the different demands on them. They want to know how it is all going to fit. We kept our eye on the ball and established this as our overarching framework. We keep UDL out in front consistently.” George Van Horne, Director of Special Education at BCSC, explains, “We looked at everything the district was doing and was required to implement and knew we needed to tie everything together. Agreeing that UDL was the framework to do this was a crucial step. From there we developed a district-wide plan. We established UDL as the overarching framework so as we add initiatives like PBIS or project-based learning the UDL principles guide their inclusion into the work.” To see a video of BSCS, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Modeling UDL at Every Level BCSC strives to enmesh UDL in every activity by modeling it at the every level, including at the administrative level. For example, when a principle gives a tour to a new school board member, they use explicit UDL language to describe activities and planning. From staff meetings to classroom planning, discussions include goals, identifying barriers to learning, and providing flexibility. Another significant shift was to have all professional development become UDL-centered. They understood that teachers needed to be scaffolded as much as the students and that the variability of teachers is as great as that of the students. Like the other districts in the UDL Implementation Project, BCSC believes that having a UDL facilitator within the district is an essential element for modeling deep understanding of UDL for the whole district. BCSC textbook and resources adoption policy that is aligned with the UDL framework is yet another structure that helps the district to model UDL at every level. UDL is Now Embedded in Teacher Evaluation Last year, BCSC started moving toward a new evaluation system. As part of the No Child Left Behind waiver the state of Indiana was mandated to create a new teacher evaluation process. BCSC views UDL as a systemic change agent and saw this as an opportunity to frame the instructional piece of the evaluation around UDL framework. They developed evaluation rubrics for teachers and other direct service providers such as: occupational therapists, physical therapists, counselors, coaches, athletic directors, building administrators, district administrators, the superintendent, and assistant superintendents. Underlying the BCSC evaluation process is a list of objectives decided upon at the very beginning of the planning and design process. According to Loui Lord Nelson, a former UDL facilitator for the district, “Their success around the development of these rubrics comes from a well-established system of support that includes a UDL point person, the constant development and availability of resources specific to UDL, and administrative knowledge of UDL and support of non-confining teaching practices as long as they are aligned with the UDL framework.” Fifty percent of the instructional score will be based on the UDL rubric. It has already made an impact. Teachers are motivated to better understand and implement UDL and are asking for more support from the UDL facilitator. A large challenge going forward for BCSC will be to make sure UDL is practiced well by the entire 700member faculty and staff. Their plan is to continue to model UDL, to scaffold teachers toward a deeper understanding and practice of UDL and to insure that proactive planning becomes a habit of the mind and not just compliance. To see a video of Loui Lord Nelson, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Teaching Students About UDL Creates Partners in Learning Bill Jensen describes a classroom in the district whose teacher assigned her class to teach the community about specific environmental issues. She believed that they would be more successful if they understood the UDL principles, so she arranged to have the district's UDL facilitator come to her classroom and spend two days teaching the students about UDL. “The students got it right away!” says Jensen. “Their summaries of UDL were unbelievable, they captured it so well.” Around the classroom comments like these were heard: “This makes me understand how I’m different as a learner” and “I understand how I can maximize my learning”. The understanding about how they learned better encouraged students to become better partners with their teachers in the learning process. To see a video of Bill Jensen, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Advice from Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation UDL needs to be the overarching framework for all other initiatives and decisions Teachers need scaffolding the same way all learners benefit from supports Having a UDL facilitator in the district is an essential support for educators Making UDL a part of teacher evaluations motivates deeper understanding and commitment to UDL Students’ learning can be maximized by understanding the UDL principles What’s Next? Next year BCSC will be piloting the newly developed educator evaluation system using a UDL rubric throughout the district. BCSC is planning UDL Implementation summer 2013 workshops for regional and national educators. District teachers who practice UDL in high fidelity will model and work together to help move them into the next phase of implementation. One of the goals is to build a library of resources and continue to develop a community of practice for all UDL educators nationwide. Other Case Stories in the UDL Implementation Series Baltimore County Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/356 Cecil County Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/359 Chelmsford Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/357 Cecil County School District Cecil County Student Demographics 84.7% White 11% African American 3% Hispanic 1% are Asian or Pacific Islander 0.3% are Native American 41.40% of total receive free/reduced meals 12.89% of total receive special education services Almost 1% of total are English Language Learners Cecil County Public Schools is a rural school district of approximately 16,000 students located in northern Maryland. CCPS has a long history of inclusionary practices, collaboration among learners of diverse abilities and high expectations for all learners. Since May 2010, administrators and teachers have been exploring the Universal Design for Learning guidelines and investigating the possibility of using UDL as a framework to guide curriculum development and instruction. For the UDL Implementation Project, district leaders identified two middle schools with eleven cross-disciplinary educators and administrators to participate in the project. Each school formed a UDL PLC that met with the UDL facilitator once a week. The district also invested in creating a robust technology system that includes full wireless network coverage and a student-to-computer ratio of approximately 3:1. Dealing with Initiative Overload is the First Challenge One of the biggest challenges to the success of UDL Implementation in CCPS is the long list of initiatives the state and the district has adopted. Administrators worried that there was a real danger of “initiative overload.” The state of Maryland had mandated UDL as a curriculum design framework and required the development of inquiry-based instruction. Cecil County middle schools were moving toward adopting the Content Literacy Continuum RTI Model (CLC) framework as a secondary intervention model and using the Strategic Instruction Model (SIM) from the Kansas Center for Research and Learning to support meaningful instruction for all learners. In addition, the district was exploring the Literacy Design Collaborative (LDC) as an instructional approach for English Language Arts and rewriting all curricula to align with the Common Core State Standards. So many mandates and initiatives can be overwhelming, but CCPS decided to focus on literacy instruction in the middle schools and used UDL as a framework to understand and implement the other initiatives. Justin Zimmerman, principal at Perryville Middle School explains, “The key component of the district’s philosophy is meeting the needs of all the learners in our schools, so using the principles and guidelines of UDL seemed like a no-brainer. We felt that a natural solution to having so many mandates and initiatives was to use UDL as an umbrella to support all upcoming curriculum writing and direct instructional change.” Deep Respect for Variability is Key A challenge for any district is for all stakeholders to gain a deep understanding of how UDL helps to address learner variability. Michael Hodnicki, Instructional Coordinator for Professional Development puts it this way,”It is more than providing flexible means of representation, action and engagement, it must come from a deep respect for the variability of the learners. What you do does not change until you change how you believe.” The district’s philosophy of respect for all learners is well matched with the UDL framework. Mr. Hodnicki continues, “It’s so easy when you see something that is so right to grab it and run, but you risk losing the depth of it that you appreciated in the first place. UDL is not how you operate; it’s how you think and what you believe in respect to students.” He suggests identifying the people who do have a deep understanding of UDL, bring them together, build a strategic plan and then build teacher expertise. Also, it is noteworthy that during the UDL implementation project, CCPS rewrote its district philosophy to incorporate UDL as an overarching framework guiding their teaching and learning framework. Professional Development Must Be a model of UDL Professional development is a high priority for CCPS. Administrators, teachers and coaches all have allocated time for it. The intention is for professional development to be on-going and connected to the district goals. Professional development occurs for teachers through coaches, extra planning time and professional development days. Mr. Hodnicki believes that UDL needs to become the fabric of the county and that one way of accomplishing this is for professional development to model UDL for educators. He explains, “Teachers have different strengths and weaknesses. Professional development should not look just one way; it needs to model what we expect them to do in their classrooms. It’s not just what we provide our kids; it’s what we also provide for our adults.” To see a video of Mike Hodnicki, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Advice from Cecil County Public Schools Grow UDL through grassroots enthusiasm, then make early initiators your UDL coaches and facilitators Build in time with creative scheduling to get together as a community to design and share lessons and to work together to incorporate UDL learning UDL facilitators or coaches are essential and need to be available more often than once a week Professional development needs to be a model of UDL Take it slow, collaborate, and make it an “all stakeholder show” What’s Next? As the district rewrites its curriculum the language of UDL will be the underpinning of the redesigned curriculum. The district plans to expand UDL PLCs into other content areas and other schools and to support and grow UDL leaders. Other Case Stories in the UDL Implementation Series Baltimore County Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/356 Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/358 Chelmsford Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/357 Chelmsford Public Schools Chelmsford Student Demographics 5,211 students 10% of all students receive free or reduced meals 15% receive special education services 2% are English Language Learners 81.5% White 3.2% African American 10.7% Asian 2.8% Hispanic 1.4% Multicultural Chelmsford Public Schools is a small suburban school district in northeastern Massachusetts. Universal Design for Learning was introduced to the Chelmsford Public School District (CPSD) four years ago after the Director of Student Services and several teachers from the district attended a UDL workshop and “were hooked.” They felt that UDL was what they needed to reach all students, both those performing at the top and the bottom of the scale. This core group of educators ignited the enthusiasm of the whole district. The district decided to start small and over the next four years invested time and resources to support educators to learn about and implement UDL. Aligning to State and District Initiatives is the First Challenge District leaders in Chelmsford believed that one of the biggest challenges to scaling up UDL in the district was to make sure there was integration with state and district initiatives requirements: Race to the Top, Common Core State Standards, and new accountability and assessments. They understood that UDL would not be successful if it was just one more initiative or requirement in their district and that aligning these initiatives with UDL would strengthen UDL implementation. So as they developed their five-year strategic plan they incorporated UDL principles into the district goals to support higher achievement of academic goals for all students. With this approach, UDL is not an add-on but a framework for decisionmaking. The plan created structures needed to embrace UDL authentically by providing professional development time for teachers to develop lesson plans and assessments, technology resources to integrate UDL cohesively, and vehicles to develop curriculum. In this way UDL is incorporated into school improvement plans, department goals, teacher practice, and instructional goals. To see a video of Kristen Rodriguez, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/resource_library/videos/udlcenter/udl. Collaboration is Key According to Dr. Kristen Rodriguez, Assistant Superintendent of Chelmsford Public School District, collaboration between educators is a primary and effective means of supporting UDL in her district. “We believe that our most important resource is our professional staff and their ability to learn from each other.” UDL started in the district with a small cohort of enthusiastic teachers. The administration listened to educator concerns and developed these strategies and structures to support them: 1) afterschool time was found for them to work together, 2) the groundwork for professional learning communities (PLCs) was laid by sending educators to PLC workshops, 3) the district partnered with three other local districts that had also taken UDL workshops to share ideas, successes and challenges. They encouraged educators to demonstrate their work through videos, created a secure online place to share lesson plans, and gave them time to develop curriculum together. There were other structures within the district that supported UDL implementation, such as infusing UDL in their co-teaching model. They found that when general education teachers worked together as co-teachers with special educators, there was an enriched level of instruction and their data indicate improvement of student scores as a result. The mentoring system in CPS is another successful approach to increasing educator knowledge and practice of UDL. Chelmsford has been integrating UDL into their mentoring practices for several years. The original cadre of educators worked within the mentoring system to create videotapes and practice lessons and presented demonstrations and workshops throughout the district. They also understand that UDL looks different in every classroom. This year they implemented a series called “UDL Make and Take” to support teachers building UDL lessons together. Dr. Rodriguez exclaims “UDL has changed teachers’ pedagogical practices altogether, and although it takes them many more hours to plan and prepare their lessons using this approach, they have found that it has been so much more successful that they do not have the need to re-teach skills.” Another approach Chelmsford is taking in the middle schools is integrating the UDL principles with literacy across the curriculum, not just in English language arts classes. They have successfully employed a “Train the trainer model” as part of the UDL implementation project. Teachers in the project developed a professional development module to scale and sustain innovative UDL practices. Starting Small Makes it Doable Dr. Katie Novak, a seventh grade English Language Arts teacher and one of the original UDL cohorts suggests, “Teachers need to start small, shoot to incorporate at least one UDL lesson a week. You just have to start. At first it’s hard, but if you do it well once and then evaluate the students work you’ll see the payoff. My students’ scores have risen; my students really love it. You have a great reputation with the parents and the administrators leave you alone because you get results.” Another strategy that Dr. Novak uses in her classroom is to engage her students as learning partners. She has created lessons to teach her students the principles of UDL. She has found that when students understand the principles of UDL they become more active in instructional decisions and are invested in what they need to do to become better learners or expert learners. Dr. Novak even has her students remind her to integrate the UDL guidelines in more of her instruction and the classroom environment. UDL Reduces the Proficiency Gap During data evaluation CPS found that a combination of UDL, co-teaching and tiered instruction were beneficial in reducing the proficiency gap for all groups by one half. The district used data collected to identify root causes of proficiency gaps and created a logic model to identify “smart” goals, to create bridges and to define strategies and action steps to attain those goals. According to Dr. Rodriguez, “We have evaluated the success of students each year using existing data like district benchmarks and nationally normed assessments and found that since the cohorts starting incorporating UDL in their classrooms, there has been student improvement in all the participating UDL classrooms.” This type of data motivates teachers to continue to develop UDL lessons and share their success with the whole community and parents are thrilled by their children’s success. To see a video of Kristen Rodriguez, go to http://www.udlcenter.org/implementation/fourdistricts/videohighlights. Technology—Offers Both an Opportunity and a Challenge Technology has been an interesting challenge for Chelmsford. Four years ago there was a lack of technology infrastructure and equipment, says Dr. Rodriguez. This was both an opportunity and a challenge for them. A common misconception about UDL is that it cannot be practiced without technology. The truth is that technology greatly enhances the integration of UDL in classrooms, but using the UDL guidelines to plan lessons, present instruction and assess students is absolutely possible without technology. To illustrate this point, a teacher cohort developed a ten-part “Make and Take” course where participants create UDL lessons that do not require technology. The focus is on deep understanding of the UDL principles and guidelines. Of course, having a robust technology environment enriches opportunities for access, engagement and flexibility, so as part of the district’s five-year strategic development plan the administration and technology department teamed up to determine infrastructure upgrades and consider capital acquisitions with UDL in mind. The town of Chelmsford has also been involved and supportive with matching funding for 21st century classrooms. Advice from Chelmsford Public School District Administrators need to understand UDL deeply, self-assess their knowledge and recognize that UDL implementation is a multi-year commitment. Establish data collection and evaluation processes to continually measure your progress. Allow flexibility: UDL looks different across classrooms and even in the same classroom each year because of different student needs. Institute UDL orientation and professional development for new administrators. The district is planning for sustainability through a “Train the Trainer” model. CPS is integrating UDL into their strategic plan so that UDL is built into every level of everyday life in the district. The 5 year strategic plan will be used to reassess integration of UDL in the district and specific mechanisms will be introduced to move toward scalability and optimization. What’s Next? The district is planning for sustainability through a “Train the Trainer” model. CPS is integrating UDL into their strategic plan so that UDL is built into every level of everyday life in the district. The 5 year strategic plan will be used to reassess integration of UDL in the district and specific mechanisms will be introduced to move toward scalability and optimization. Other Case Stories in the UDL Implementation Series Baltimore County Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/356 Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/358 Cecil County Public Schools: http://www.udlcenter.org/node/359