The legal opinion in full

advertisement

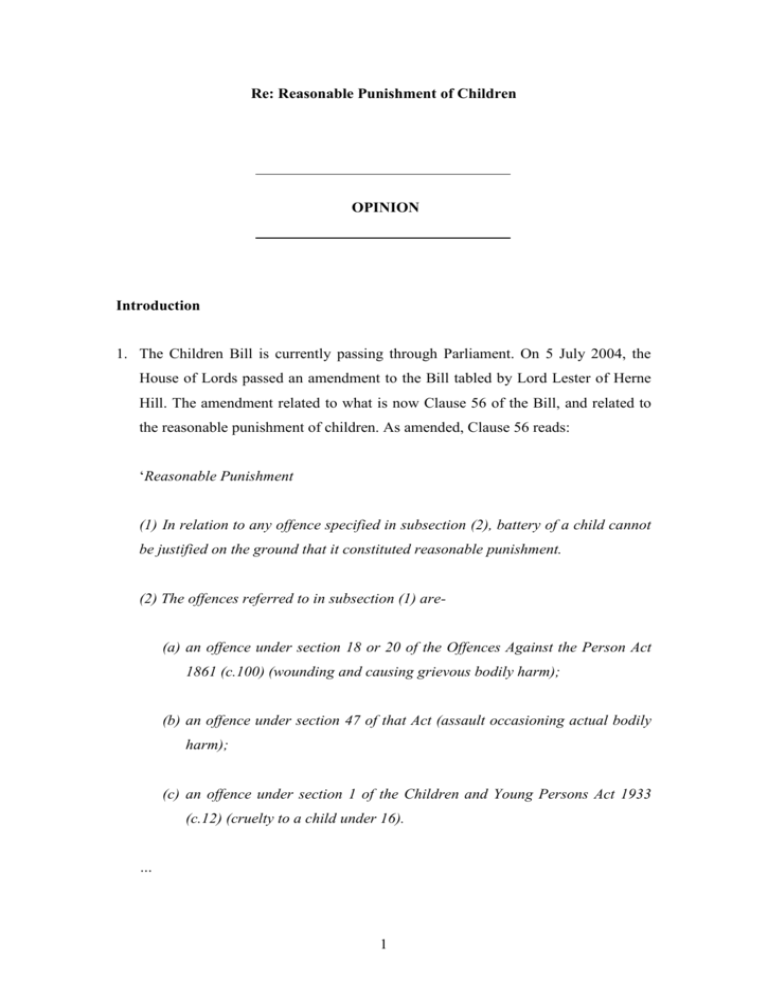

Re: Reasonable Punishment of Children OPINION Introduction 1. The Children Bill is currently passing through Parliament. On 5 July 2004, the House of Lords passed an amendment to the Bill tabled by Lord Lester of Herne Hill. The amendment related to what is now Clause 56 of the Bill, and related to the reasonable punishment of children. As amended, Clause 56 reads: ‘Reasonable Punishment (1) In relation to any offence specified in subsection (2), battery of a child cannot be justified on the ground that it constituted reasonable punishment. (2) The offences referred to in subsection (1) are- (a) an offence under section 18 or 20 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 (c.100) (wounding and causing grievous bodily harm); (b) an offence under section 47 of that Act (assault occasioning actual bodily harm); (c) an offence under section 1 of the Children and Young Persons Act 1933 (c.12) (cruelty to a child under 16). … 1 (5) In section 1 of the Children and Young Persons Act 1933, omit subsection (7).’ 2. The effect of Clause 56 is to abolish, in cases where actual bodily harm, grievous bodily harm or wounding is caused, the common law rule that a parent or any other person acting in loco parentis may administer reasonable corporal punishment to control the behaviour of a child. It will still be permissible for parents to administer reasonable physical punishment where no such harm is caused. 3. We have been asked to advise on the effect Clause 56 is likely to have in practice, and in particular on the implications of abolishing the common law rule in cases where the punishment which is administered causes actual bodily harm. The Legal Background Battery 4. A battery involves an unlawful and unwanted contact with the body of another. It must be committed intentionally or recklessly. 5. A battery can be committed without the victim suffering any kind of injury. Thus, any touching can constitute a battery: R –v- Thomas (1985) 81 Cr.App.R. 331. It does not necessary involve a harming of the body and this can be shown by the fact that a battery can take place even if the victim did not feel the touching. 6. The fundamental principle is that every person’s body is inviolate. The principle is, however, subject to a number of exceptions, such as the use of reasonable force in self-defence or out of necessity and the lawful exercise of the power of arrest. A broader exception has been created to allow for the exigencies of everyday life: Collins –v- Wilcock [1984] 1 W.L.R. 1173 (per Goff L.J.). The kind of behaviour which falls within this broader exception includes the administration of reasonable punishment to children, pushing in order to get onto a crowded tube train and tapping a person on the shoulder to attract his or her attention. 2 Actual Bodily Harm 7. Section 47 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 provides: ‘Whosoever shall be convicted upon indictment of any assault occasioning actual bodily harm shall be liable…to be imprisoned for any term not exceeding five years.’ 8. The offence involves a battery which occasions actual bodily harm. (For the present purposes, it is unnecessary to explore the distinction between an ‘assault’ and a ‘battery’.) 9. The phrase ‘actual bodily harm’ has been defined as ‘any hurt or injury calculated to interfere with the health or comfort’ of the victim: R –v- Donovan [1934] 2 K.B. 498. The harm need not be permanent but it should ‘not be so trivial as to be wholly insignificant’: R –v- Chan Fook [1994] 1 W.L.R. 689 (at 696). For example, the causing of tenderness, bruising, grazes, temporary loss of consciousness or breaking of teeth are capable of amounting to actual bodily harm. In Ireland [1998] A.C. 147, the House of Lords held that psychological injuries could be included within the term ‘actual bodily harm’, but only if they were medically recognised conditions which involved more than fear, panic or distress. The Effect of Clause 56 in Practice Overview 10. The effect of Clause 56 is that the defence of reasonable punishment will remain available for the offence of battery, but not for the offence of assault occasioning actual bodily harm. 3 11. It follows that a parent who commits a minor battery on his or her child – for example, a quick smack in a supermarket whilst the child is throwing a tantrum – will be guilty of a criminal offence if the smack causes actual bodily harm, such as tenderness. The offence will be committed regardless of whether the smack is administered by a loving parent as a ‘one-off’ punishment, or as part of a pattern of abuse by a parent with a history of violence. The Charging Standards: Battery (Common Assault) or Actual Bodily Harm 12. The decision to charge an instance of unlawful touching as battery (or the similar offence of common assault) or as actual bodily harm will depend on an assessment by the police or the Crown Prosecution Service (‘CPS’) of the seriousness of the harm which has been caused. 13. In an attempt to achieve a consistent approach across the country, in 1996 the police and the CPS issued Charging Standards in relation to offences against the person. These standards operate as guidelines, and are neither prescriptive nor enforceable. 14. The Charging Standards state that common assault will generally be the appropriate charge where the injuries amount to no more than grazes, minor bruising, reddening of the skin, scratches, superficial cuts or a black eye. A charge of actual bodily harm may be justified “in exceptional circumstances”, or where the maximum sentence for common assult would be inadequate. 15. However, during the debate in the House of Lords on Lord Lester’s amendment, the Attorney General stated that the Director of Public Prosecutions intended to issue revised Charging Standards: Handsard, H.L. Deb. July 5, 2004, Col 563. The proposed revision would give guidance to prosecutors to focus not just on the nature of the injury when deciding the appropriate charge, but also on the vulnerability of the victim: ‘The revised charging standard will include guidance that where serious aggravating features exist, cases in which the level of injuries would usually lead 4 to a charge of common assault, could more appropriately be charged as actual bodily harm. Such serious aggravating features would include the vulnerability of the victim, such as when they are a child assaulted by an adult. The effect of that pending change is that even minor assaults by a parent on a child, where grazes, scratches, abrasions, minor bruising, swelling, superficial cuts or a black eye are caused, will normally be charged as assault occasioning actual bodily harm. However, given the publicity over the weekend and this morning, I should make it clear that reddening of the skin where it is merely transitory will usually still be charged as common assault.’ 16. As the Attorney General identified, the effect of the proposed revision would be to give to prosecutors guidance that, where a parent smacks his or her child, and the smack causes grazes, scratches, abrasions, minor bruising, swelling or, presumably, tenderness, the appropriate charge will normally be assault occasioning actual bodily harm, rather than battery. 17. In assessing the protection the Charging Standards, revised or unrevised, may afford a loving parent who commits a minor assault on his or her child, the following matters are relevant: a. The standards apply to the police and the CPS, but not to other prosecuting agencies or to private prosecutions; b. The standards are guidelines, and are not prescriptive or enforceable; c. In each case, the standards are considered by the prosecutor. Different prosecutors, faithfully considering the standards, may take different views on the same facts; and d. Accordingly, there is a possibility that where in one case a parent is charged with battery, in another case, a parent who has in all material respects acted in exactly the same way will be charged with assault occasioning actual bodily harm. 5 The Decision to Prosecute: The Code for Crown Prosecutors 18. All cases referred to the CPS are reviewed in accordance with the Code for Crown Prosecutors (‘the Code’). In order for a prosecution to be commenced or to continue, the prosecutor must be satisfied that: a. There is sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction (the evidential test); and b. It is in the public interest to prosecute (the public interest test). 19. In deciding whether it is in the public interest to prosecute a parent for assulting his or her child, the prosecutor must take into account the interests and welfare of the child. 20. Where the case involves a minor battery by a parent (such as a quick smack in a supermarket) which has caused actual bodily harm, the prosecutor’s consideration of the public interest test may in many instances result in a decision not to prosecute. 21. However, in our opinion, the public interest test is unlikely to prevent the prosecution of such cases altogether. In assessing the protection the test may afford a loving parent who commits a minor assault on his or her child, the following matters are relevant: a. The Code applies to the police and the CPS, but not to private prosecutions. (Any individual has the right to instigate a private prosecution. The Director of Public Prosecutions has the power to take over the conduct of such prosecutions); b. The public interest test is not a test of principle. It depends on an assessment by a prosecutor. Different prosecutors, faithfully applying the Code, may take different views on the same facts; and 6 c. Accordingly, there is a possibility that, where in one case a parent is not prosecuted for any offence, in another case, a parent who has in all material respects acted in exactly the same way will be prosecuted for assault occasioning actual bodily harm. Conclusions 22. The effect of Clause 56 is that the defence of reasonable punishment will remain available for the offence of battery (and the offence of common assault), but not for the offence of assault occasioning actual bodily harm. 23. By abolishing the common law rule of reasonable punishment in cases of actual bodily harm, the effect of Clause 56 is that a parent who commits a minor battery on his or her child will be guilty of the offence if the smack causes injuries such as bruising or tenderness. 24. If the Charging Standards are revised as the Attorney General has described, cases where a parent has smacked his or her child and caused a minor injury will normally be charged as assault occasioning actual bodily harm, rather than as battery. 25. The interests of justice test contained in the Code and the Charging Standards require an assessment to be carried out by the prosecutor on a case by case basis. Different prosecutors may take different views on the same facts. 26. Accordingly, it is possible that where in one case a parent is prosecuted for assault occasioning actual bodily harm, in another case a parent, who in all material respects has acted in exactly the same way, will be prosecuted for battery or not prosecuted at all. ROY AMLOT Q.C. 7 LOUIS MABLY 6 KING’S BENCH WALK LONDON EC4 26 October 2004 8