emily dickinson, 1830-1886 - Faculdade de Letras

advertisement

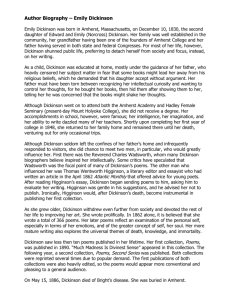

chapter 1. biography and main works.............................. 115 chapter 2. Introduction to “Emily Dickinson” ................... 117 chapter 3. selected poems ...................................... 119 ATTENTION! NOTICE ABOUT COPYRIGHT The texts that comprise this unit have been extracted from a selected bibliography. You MUST quote those sources – and not this booklet (“apostila”) - any time you use the texts to write an academic essay. You will find the page numbers of the original passages within square brackets, [ ], so that you can provide the correct bibliographical references. For more information on How to write an academic essay check the Professor’s website: www.letras.ufrj.br/veralima UNIT III- SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY CHAPTER 1 & 3 MCMICHAEL, George [Editor]. Concise Anthology of American Literature. 2 a edição. New York: Macmillan, 1986 CHAPTER 2 KNAPP, Bettina. Emily Dickinson. New York: Continuum, 1989. 202 pp. 113 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON 114 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON EMILY DICKINSON, 1830-1886 chapter 1. biography and main works George MCMICHAEL [1025] One day in April 1862, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a poetry critic for The Atlantic Monthly, received a letter from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, Massachusetts, asking, "Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?" The four poems she enclosed provoked an immediate response and began a correspondence that lasted twenty-two years. Although Emily Dickinson thanked her "preceptor" Higginson for the "surgery" he performed on her poetry, she wanted his encouragement more than his advice, and she politely ignored his suggestions for regularizing her rough rhythms and imperfect rhymes and for correcting her spelling and grammar. Recognizing Emily Dickinson's poetic genius, despite her violations of poetic convention, Higginson remained her friend and adviser throughout her life, and after her death he assisted in gathering her poems for publication. Only eight of Emily Dickinson's poems were published while she lived, and it was not until the appearance of Poems by Emily Dickinson (1890), four years after her death, that her work became available to the general reading public for the first time.^ The early critical estimates were mixed. Some reviewers found the poetry "balderdash" suffering from lack of rhyme, faulty grammar, and incomprehensible metaphors, a "farrago of illiterate and uneducated sentiment." But other readers found them remarkably pointed and evocative. As the years passed and as more poems were published, critical estimates grew more favorable until, with the publication of all her known poetry, in The Poems of Emily Dickinson (1955), the shy, reclusive poet had come to be regarded, with Whitman and Poe, as one of America's greatest lyric poets. The range of Emily Dickinson's worldly experience was small by any standard. Her entire life, except for brief visits to nearby Boston and to Washington, D.C., was spent in and around her birthplace, Amherst. The Dickinsons of Amherst were prominent. Her grandfather was a founder of Amherst College; for seventy years her father and then her brother, both lawyers, served as College Treasurer and Trustee. Her mother claimed 115 [1026] Emily's affection, but not her wholehearted respect: "Mother does not care for thought," she wrote to Higginson. As Emily Dickinson grew older, she increasingly withdrew from society, seldom leaving her garden and her large family house. There she wrote poems and letters to her friends and watched the life of the town from her upstairs bedroom window. Her friends, she said, were her "estate," and among them were men, other than Higginson, her father, and her brother, who profoundly affected her creative and emotional life. One of them was her second "preceptor," the Reverend Charles Wadsworth, whom she met in Philadelphia in the mid-1850$. The facts of their relationship are obscure, but there is little doubt about her love for him and for his "kindly spiritual counsel," although they seldom met, and he was a married man with a family. His departure to California perhaps caused the emotional crisis she experienced in 1862, provoking a great creative outburst, for in that single year she wrote the astonishing total of j 66 poems. Emily Dickinson lived a more intense and passionate life than was thought by neighbors and acquaintances who saw her only as an eccentric maiden lady, the "moth" of Amherst, dressed only in white, who flitted almost ghostlike through her house and garden. Not even those closest to her knew fully the depth and extent of her emotions or that the nearly 1,800 poems, tied neatly in packets found after her death, would reveal an immensely complex and passionate sensibility. Her subjects were love, death, nature, immortality, beauty. Written largely in meters common to Protestant hymn books, her poems employed irregular rhythms, off- or slantrhymes, paradox, and a careful balancing of abstract Latinate and concrete Anglo-Saxon words. Her lines were gnomic and her images kinesthetic, highly concentrated, and intensely charged with feeling. Her greatest lyrics were on the theme of death, which she typically personified as a monarch, a lord, or a kindly but irresistible lover, yet her moods varied widely, from melancholy to exuberance, grief to joy, leaden despair to spiritual intoxication. UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON Emily Dickinson's poetry at times descended to coyness and sentimentality. She had no firsthand contact with contemporary writers or critics of the highest order. Her favorite authors included Shakespeare, Keats, the Brownings, Ruskin, and Sir Thomas Browne, whose uneasy balance of faith and skepticism she shared. Early in life she rebelled against the Calvinism of the Amherst Congregational Church, yet she retained the Calvinist tendency to look inwardly, and she had a Calvinist sense of both the inherent beauty and the frightening coldness of the world. With her fellow New Englanders Jonathan Edwards and Emerson, she perceived beauty in the wholeness and harmonious relationships of nature, and like Edwards and Emerson she has come to stand as a dominant figure in her nation's literary history, a poet whose work reflects a spiritual unrest and a sense of the _ human predicament that defy all easy categories. FURTHER READING: The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. T. Johnson, 1960, 1976; The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson, ed. R. Franklin, 1981; The Letters of Emily Dickinson, 3 vols., ed. T. Johnson, 1955; J. Leyda, The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson, 2 vols., 1960; G. Whicher, This Was a Poet, 1938, 1952, 1957; M. Bingham, Ancestor's Brocades, 1945, 1967; R. Chase, Emily Dickinson, 1951; T.Johnson, Emily Dickinson, ig55;T. Ward, The Capsule of the Mind, 1961; D. Higgins, Portrait of Emily Dickinson, 1967; The Recognition of Emily Dickinson, ed. C. Blake and C. Wells, 1964; A. Gelpi, Emily Dickinson, 1965; K. Lubbers, Emily Dickinson, the Critical Revolution, 1968; J. Pickard, Emily Dickinson, an Introduction and Interpretation, 1967; C. Anderson, Emily Dickinson's Poetry, 1960; C.Griffith, The Long Shadow, Emily Dickinson's Tragic Poetry, 1964; R. Miller, The Poetry of Emily Dickinson, 1968; E. Wylder, Emily Dickinson's Manuscripts, 1971; R. Sewall, The Life of Emily Dickinson, 1974; R. Weisbuch, Emily Dickinson's Poetry, 1975; P. Ferlazzo, Emily Dickinson, 1976; S. Cameron, Lyric Time, Dickinson and the Limits of Genre, 1979; K. Keller, The Only Kangaroo Among the Beauty, 1979; D. Porter, Dickinson the Modern Idiom, 1981; J. Diehl, Dickinson and the Romantic Imagination, 1981; J. Juhasz, The Undiscovered Continent, Emily Dickinson and the Space of the Mind, 1983. IMPORTANT!! All references and numbering to Emily Dickinson’s poems are in 116 keeping with The Poems of Emily Dickinson, 3 vols.; ed. T. Johnson, 1955. That is the compilation about Emily Dickinson preferred in scholarly research. However, not all anthologies – mainly the new ones on the Internet – comply with Johnson’s numbering system. UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON chapter 2. Introduction to “Emily Dickinson” Bettina KNAPP [9] To read the poetry and letters of Emily Dickinson is to marvel at the extraordinary modernity and rigor of her ideas, at the courage and strength of her nonconformity, and at the manner in which she overcame patriarchal dominance. It is to be excited and haunted by the mystery of her elusive thought, which lies buried in what might be alluded to as the geological folds of her verse. Dickinson's was a poetry for all time, no longer to be understood only in terms of her immediate background in a puritanical, Transcendentalist-tinged nineteenth-century small town. Her verbal and ideological innovations arose from her inborn talent, but also stemmed in part from her boldness and heroic temperament; she kept a firm desire to be emotionally and intellectually independent, as a person in her own right. At a time when women enjoyed virtually no intellectual freedom, Dickinson chose to carve out her own role. Although adhering to the strict social regulations imposed on a refined Amherst girl, she nevertheless had a mind of her own and a will of iron. No one could tell her how to think or how to write. So determined was she in thinking things out for herself that she even rejected the tenets of her church. The course she chose for herself is perhaps best understood when considering the fact that she had come from very solid stock. Paradoxically, she was a product of her background: a Protest-ant in the real sense of the word. A spirit of contest, inquiry, and continuous transformation prevailed in Dickinson's search for true form, meaning, and faith. Her analytical and probing mind helped her to face pain and doubt and concomitantly increased her feelings of self-worth. [10]After its transition from the uncreated to the created, the inaudible to the audible, the invisible to the visible, the word not only took on flesh but became Dickinson's armament, her ammunition. The word was Dickinson's livingness, actuality, dynamism. As it catalyzed and interacted with other morphemes in the verse, the word impacted on her and the reader as well. For Dickinson, as for the mystic, language was a sign, a mask, a 117 protection, and a shelter for her oblique thoughts. It helped her to carve the bedrock of her ambiguous and always fleeting feelings. Verbalization was crucial in helping her face aspects of life to which she reacted traumatically: Creation, Death, God, Love, Sex, Nature. Only in hermetic terms could Dickinson convey the complexity and ambiguity of her intellectual meanderings. Like the ancient Orphics and the modern Surrealists, she manipulated her consecrated gleamings in encoded messages, from timeless and spaceless regions. Drawing from her "box of phantoms," which contained the nourishment necessary to recount her turmoil, she engaged in her secret activity of writing in the privacy and silence of her room: Pain —has an Element of Blank— It cannot recollect When it begun—or if there were A time when it was not— It has no Future—but itself— Its Infinite contain Its Past—enlightened to perceive New Periods—of Pain. (#650) Poetry, for Dickinson, was a celebration of .the creative power of the word. Only partially articulated truths and ambiguous syntax were molded by her into sculptured verse, which she then smoothed and refined into what we might consider occult diachronic and synchronic progressions. Placing her figures of speech and cryptic allusions in special spaces within the line, Dickinson was able to locate and isolate nonmaterial thoughts and sensations, thereby arousing the reader's fascination and spirit of inquiry. That hers was a poetry both classical in quality and contemporary in technique in no way intimates its accessibility. Quite the [11] contrary: Dickinson's verses are for the most part impenetrable. Esoteric in nature, behind her private metaphoric mode, forms, and organic shapes there lies a world hidden or buried in darkness that readers attempt to experience according to their own understanding. UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON Poetry restored to Dickinson what had been lost, located what had been missing, and renewed what had been corroded. It was her lifeline to the world: "she ate and drank the precious words," endowing them with a fresh life culled from her private lexicon of symbols, signs, and totems. Like the symbolists, Dickinson felt that a correspondence— subtle, forever fluctuating, and unnameable—existed between spiritual ideations and empirical reality. To use everyday terminology in her poetry, but in a new way, as had Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Verlaine, and Stephane Mallarme, was to inject new energy into colloquialisms, thereby altering their meaning, impact, and resonance. The Lightning is a yellow Fork From Tables in the sky By inadvertently fingers dropt The awful Cutlery (#1173) I felt a Cleaving in my Mind— As if my Brain had split— I tried to match it—Seam by Seam— But could not make them fit. (#937) Like the work of Samuel Beckett, which cannot be categorized, so Dickinson's word must be examined for its infinite implications, each being a microcosm of the macrocosm. Poetic creation, for Dickinson, was like the opening of doors and windows onto an unknown and frequently monstrous world: I've seen a Dying Eye Run round and round a Room (#547) Visual in every way, Dickinson's poems are verbal transliterations of the New England portraiture and landscape paintings of her day, rigorous and outwardly simple, without great consideration for perspective. As visual dramas ("A Bird came down the Walk— / He did not know I saw," *328), they are as clear, concise, and precise as the drawings of John James Audubon. Cut off from the fustian fineries of her day, she saw mercilessly into nature's raw and rapacious world, both menacing and enthralling, beauteous and ugly. Her concretization of abstract concepts, the singling out of parts of the body to determine states of mind, and her mathematical notions—the "static representation of movement," to quote Marcel Duchamp's paradoxical description of his painting Nude Descending a Staircase—actually liken her to the twentieth-century Dadaists, Surrealists, Expressionists, and Abstract Expressionists. [12]Like the Dadaists and Surrealists, Dickinson uses words according to her own unconventional understanding of them, without embellishment. They stand solitary, like one of Giorgio De Chi-rico's heads on a street, detached, uncentered, thrust there by some happenstance; or like one of Dali's clocks, bent to fit the sides of a low wall. Reminiscent of the Expressionists and Abstract Expressionists, Dickinson sometimes conveys her subjective feelings in violent distortions rather than in ordered representations, thereby underscoring the terror, pathos, and agony of the moment. 118 leading on through inner circular paths of memory, recollection, contradiction, where nothing is fixed. "I dwell in Possibility," Dickinson wrote. Despite the fluidity of her thought and sensations, the certainty of her course made of her inner world a fortress "Impregnable of Eye." (#657) Secretly and privately, "How powerful the Stimulus / Of an Hermetic Mind," she forged on. (#711) A Word made Flesh. . . . A Word that breathes distinctly Has not the power to die. . . . (#1651) psP UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON chapter 3. selected poems 1 l written in 1858 8 There is a word Which bears a sword Can pierce an armed man -It hurls its barbed syllables And is mute again -But where it fell The saved will tell On patriotic day, Some epauletted Brother Gave his breath away. Wherever runs the breathless sun -Wherever roams the day -There is its noiseless onset -There is its victory! Behold the keenest marksman! The most accomplished shot! Time’s sublimest target Is a soul "forgot!" Few of Dickinson’s poems have titles. The numbers used here follow the reference edition of her works, The Poems of Emily Dickinson, 3 vols.; ed. T. Johnson, 1955, which contains 1775 poems, all of them numbered. The footnotes below were extracted from Mc Michael’s anthology. Writing years are presumed. [Note by Vera ] 1 119 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON To the ecstacy. 49 I never lost as much but twice, And that was in the sod. Twice have I stood a beggar Before the door of God! For each beloved hour Sharp pittances of years— Bitter contested farthings— And Coffers heaped with Tears! Angels—twice descending Reimbursed my store— Burglar! Banker—Father! I am poor once more! l written in 1859 67 Success is counted sweetest By those who ne'er succeed. To comprehend a nectar Requires sorest need. Not one of all the purple Host Who took the Flag today Can tell the definition So clear of Victory As he defeated—dying— On whose forbidden ear The distant strains of triumph Burst agonized and clear! 125 For each ecstatic instant We must an anguish pay In keen and quivering ratio 120 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON 130 Mirth is the Mail of Anguish— In which it Cautious Arm, Lest anybody spy the blood And "you're hurt" exclaim! These are the days when Birds come back— A very few—a Bird or two— To take a backward look. These are the days when skies resume The old—old sophistries of June— A blue and gold mistake. 185 "Faith" is a fine invention When Gentlemen can see— But Microscopes are prudent In an Emergency. Oh fraud that cannot cheat the Bee— Almost the plausibility Induces my belief. Till ranks of seeds their witness bear— And softly thro' the altered air Hurries a timid leaf. Oh Sacrament of summer days, Oh Last Communion in the Haze— Permit a child to join. Thy sacred emblems to partake— Thy consecrated bread to take And thine immortal wine! l written in 1860 165 A Wounded Deer—leaps highestI've heard the Hunter tell— 'Tis but the Ecstasy of death— And then the Brake is still! The Smitten Rock that gushes! The trampled Steel that springs! A Cheek is always redder Just where the Hectic stings! 121 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON Till Seraphs3 swing their snowy Hats— And Saints—to windows run— To see the little Tippler From Manzanilla4 come!5 210 The thought beneath so slight a film— Is more distinctly seen— As laces just reveal the surge— Or Mists—the Appenine— l written in 1861 214 216 I taste a liquor never brewed— From Tankards scooped in Pearl— Not all the Frankfort Berries2 Yield such an Alcohol! Safe in their alabaster chambers, Untouched by morning and untouched by noon, Sleep the meek members of the resurrection, Rafter of satin, and roof of stone. Inebriate of Air—am I— And Debauchee of Dew— Reeling—thro endless summer days— From inns of Molten Blue— Light laughs the breeze in her castle of sunshine; Babbles the bee in a stolid ear; Pipe the sweet birds in ignorant cadences, -Ah, what sagacity perished here! When "Landlords" turn the drunken Bee Out of the Foxglove's door— When Butterflies—renounce their "drams"— I shall but drink the more! Grand go the Worlds scoop Diadems drop Soundless as years in the crescent above them; their arcs, and firmaments row, and Doges surrender, dots on a disk of snow. 280 I felt a Funeral, in my Brain, And Mourners to and fro Kept treading -- treading -- till it seemed That Sense was breaking through -And when they all were seated, A Service, like a Drum -- 3 The highest ranking of the nine orders of angels A sherry wine exported from Manzanilla, Spain. 5 Two other versions of the final line exist: "Come staggering toward the sun." "Leaning against the—-sun—" 4 2 Grapes grown in the region of Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and used in making a fine Rhine wine. Another version of this line reads, "Not all the Vats upon the Rhine." 122 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON Kept beating -- beating -- till I thought My Mind was going numb -- Nods from the Seconds slim -Decades of Arrogance between The Dial life -And Him -- And then I heard them lift a Box And creak across my Soul With those same Boots of Lead, again, Then Space -- began to toll, As all the Heavens were a Bell, And Being, but an Ear, And I, and Silence, some strange Race Wrecked, solitary, here -And And And And then a Plank in Reason, broke, I dropped down, and down -hit a World, at every plunge, Finished knowing -- then -- 287 A Clock stopped -Not the Mantel’s -Geneva’s farthest skill Can’t put the puppet bowing -That just now dangled still -An awe came on the Trinket! The Figures hunched, with pain -Then quivered out of Decimals -Into Degreeless Noon -It will not stir for Doctors -This Pendulum of snow -This Shopman importunes it -While cool -- concernless No -Nods from the Gilded pointers -123 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON Earn her own surprise! l written in 1862 But -- should the play Prove piercing earnest -Should the glee -- glaze -In Death’s -- stiff -- stare -- 328 A Bird came down the Walk -He did not know I saw -He bit an Angleworm in halves And ate the fellow, raw, Would not the fun Look too expensive! Would not the jest -Have crawled too far! And then he drank a Dew From a convenient Grass -And then hopped sidewise to the Wall To let a Beetle pass -He glanced with rapid eyes That hurried all around -They looked like frightened Beads, I thought -He stirred his Velvet Head Like one in danger, Cautious, I offered him a Crumb And he unrolled his feathers And rowed him softer home -Than Oars divide the Ocean, Too silver for a seam -Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon Leap, plashless as they swim. 338 I know that He exists. Somewhere -- in Silence -He has hid his rare life From our gross eyes. ‘Tis an instant’s play. ‘Tis a fond Ambush -Just to make Bliss 124 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON 375 And let you from a Dream -As if a Goblin with a Gauge -Kept measuring the Hours -Until you felt your Second The Angle of a Landscape -That every time I wake -Between my Curtain and the Wall Upon an ample Crack -- Weigh, helpless, in his Paws -And not a Sinew -- stirred -- could help, And sense was setting numb -When God -- remembered -- and the Fiend Like a Venetian -- waiting -Accosts my open eye -Is just a Bough of Apples -Held slanting, in the Sky -The Pattern of a Chimney -The Forehead of a Hill -Sometimes -- a Vane’s Forefinger -But that’s -- Occasional -- Let go, then, Overcome -As if your Sentence stood -- pronounced -And you were frozen led From Dungeon’s luxury of Doubt To Gibbets, and the Dead -- The Seasons -- shift -- my Picture -Upon my Emerald Bough, I wake -- to find no -- Emeralds -Then -- Diamonds -- which the Snow And when the Film had stitched your eyes A Creature gasped "Reprieve"! Which Anguish was the utterest -- then -To perish, or to live? From Polar Caskets -- fetched me -The Chimney -- and the Hill -And just the Steeple’s finger -These -- never stir at all -- 441 This is my letter to the World That never wrote to Me -The simple News that Nature told -With tender Majesty 414 ‘Twas like a Maelstrom, with a notch, That nearer, every Day, Kept narrowing its boiling Wheel Until the Agony Her Message is committed To Hands I cannot see -For love of Her -- Sweet -- countrymen -Judge tenderly -- of Me Toyed coolly with the final inch Of your delirious Hem -And you dropt, lost, When something broke -- 520 I started Early -- Took my Dog -125 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON And visited the Sea -The Mermaids in the Basement Came out to look at me -And Frigates -Extended Hempen Presuming Me to Aground -- upon 619 Glee -- The great storm is over -Four -- have recovered the Land -Forty -- gone down together -Into the boiling Sand -- in the Upper Floor Hands -be a Mouse -the Sands -- Ring -- for the Scant Salvation -Toll -- for the bonnie Souls -Neighbor -- and friend -- and Bridegroom -Spinning upon the Shoals -- But no Man moved Me -- till the Tide Went past my simple Shoe -And past my Apron -- and my Belt -And past my Bodice -- too -- How they will tell the Story -When Winter shake the Door -Till the Children urge -But the Forty -Did they -- come back no more? And made as He would eat me up -As wholly as a Dew Upon a Dandelion’s Sleeve -And then -- I started -- too -- Then a softness -- suffuse the Story -And a silence -- the Teller’s eye -And the Children -- no further question -And only the Sea -- reply -- And He -- He followed -- close behind -I felt his Silver Heel Upon my Ankle -- Then my Shoes Would overflow with Pearl -Until We met the Solid Town -No One He seemed to know -And bowing -- with a Might look -At me -- The Sea withdrew -- 126 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON The Wind -No nearer Neighbor -- have they -But God -- l written in 1863 712 Because I could not stop for Death -He kindly stopped for me -The Carriage held but just Ourselves -And Immortality. The Acre gives them -- Place -They -- Him -- Attention of Passer by -Of Shadow, or of Squirrel, haply -Or Boy -- We slowly drove -- He knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility -We At We We passed Recess passed passed What Deed is Theirs unto the General Nature -What Plan They severally -- retard -- or further -Unknown -- the School, where Children strove -- in the Ring -the Fields of Gazing Grain -the Setting Sun -- Or rather -- He passed Us -The Dews drew quivering and chill -For only Gossamer, my Gown -My Tippet -- only Tulle -We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground -The Roof was scarcely visible -The Cornice -- in the Ground -Since then -- ‘tis Centuries -- and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses’ Heads Were toward Eternity -- 742 Four Trees -- upon a solitary Acre -Without Design Or Order, or Apparent Action -Maintain -The Sun -- upon a Morning meets them -127 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON And opens further on -He likes a Boggy Acre A Floor too cool for Corn -Yet when a Boy, and Barefoot -I more than once at Noon Have passed, I thought, a Whip lash Unbraiding in the Sun When stooping to secure it l written in 1864 894 Of Consciousness, her awful Mate The Soul cannot be rid -As easy the secreting her Behind the Eyes of God. The deepest hid is sighted first And scant to Him the Crowd -What triple Lenses burn upon The Escapade from God -- It wrinkled, and was gone -Several of Nature’s People I know, and they know me -I feel for them a transport 967 Pain -- expands the Time -Ages coil within The minute Circumference Of a single Brain -Pain contracts -- the Time -Occupied with Shot Gamuts of Eternities Are as they were not -- l written in 1865 986 A narrow Fellow in the Grass Occasionally rides -You may have met Him -- did you not His notice sudden is -The Grass divides as with a Comb -A spotted shaft is seen -And then it closes at your feet 128 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON Of cordiality -But never met this Fellow Attended, or alone Without a tighter breathing And Zero at the Bone -- Italicized -- as ‘twere. As We went out and in Between Her final Room And Rooms where Those to be alive Tomorrow were, a Blame l written in 1866 That Others could exist While She must finish quite A Jealousy for Her arose So nearly infinite -- 1068 Further in Summer than the Birds Pathetic from the Grass A minor Nation celebrates Its unobtrusive Mass. We waited while She passed -It was a narrow time -Too jostled were Our Souls to speak At length the notice came. No Ordinance be seen So gradual the Grace A pensive Custom it becomes Enlarging Loneliness. Antiquest felt at Noon When August burning low Arise this spectral Canticle Repose to typify Remit as yet no Grace No Furrow on the Glow Yet a Druidic Difference Enhances Nature now 1100 The last Night that She lived It was a Common Night Except the Dying -- this to Us Made Nature different We noticed smallest things -Things overlooked before By this great light upon our Minds 129 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON l written in 1881 She mentioned, and forgot -Then lightly as a Reed Bent to the Water, struggled scarce -Consented, and was dead -- 1518 Not seeing, still we know -Not knowing, guess -Not guessing, smile and hide And half caress -And quake -- and turn away, Seraphic fear -Is Eden’s innuendo "If you dare"? And We -- We placed the Hair -And drew the Head erect -And then an awful leisure was Belief to regulate -- l written in 1870 1173 The Lightning is a yellow Fork From Tables in the sky By inadvertent fingers dropt The awful Cutlery Of mansions never quite disclosed And never quite concealed The Apparatus of the Dark To ignorance revealed. l written in 1872 1233 Had I not seen the Sun I could have borne the shade But Light a newer Wilderness My Wilderness has made -- 130 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON l “date unknown” 1695 There is a solitude of space A solitude of sea A solitude of death, but these Society shall be Compared with that profounder site That polar privacy A soul admitted to itself -Finite infinity. 131 UNIT V – EMILY DICKINSON cartoon available at http://www.cabanonpress.com/News/news-5.ED.htm 132