Higher Biology: Genome - Personal Genomics

advertisement

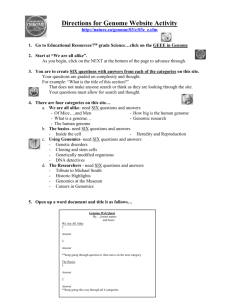

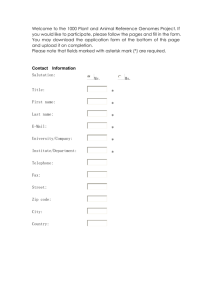

PERSONAL GENOMICS 1.3 Genome: d (iii) Personal Genomics From the Arrangements Analysis of an individual’s genome may lead to personalised medicine (pharmacogenetics) through knowledge of the genetic component of risk of disease and likelihood of success of a particular tr eatment. The difficulties in distinguishing between neutral and harmful mutations in both genes and regulatory sequences, and in understanding the complex nature of many diseases. Teacher’s notes There are two activities. The first is a straightforward read the information card and answer questions. The second is a ‘diamond 9’ pairs activity. 1. Summary questions As an introduction you may wish to show this short 4-minute video clip, which introduces the 1000 genome project. http://genome.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTX063334.html Point out the banks of computers, occupying whole floors of buildings, which are needed to analyse sequence information. There is an information card and a question sh eet. The questions are based on the information card. 2. Diamond 9 pairs game Collect a set of nine cards for each discussion group. Arrange them into a diamond shape. To do this look at the information on them and arrange them in the order that you think is most important. UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 1 PERSONAL GENOMICS When you are finished the cards should look like this: Most important Least important 2 UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 After each group has finished the activity get a person from each pair to explain why they chose that particular order. Highlight if there were any differences in the layout of cards for each group. PERSONAL GENOMICS Summary questions Learning objectives By completing these questions you will know what is meant by the term pharmacogenetics. You will realise that the action of drugs is complex and may be affected at several levels. You will know that different people respond to drugs differently and there is an underlying genetic influence on the action of drugs. You will know that variation within humans is significant but can be analysed and personalised to specific treatments. Use the information card to help you answer these questions. 1. What is pharmacogenetics? 2. So far, what has pharmacogenetics research largely focused on? 3. What sort of genetic tests are now being developed? 4. What are the pharmacological consequences of genetic variation? 5. What is it about an enzyme that makes it fully functional? 6. Where might mutations occur that would ultimately affect a protein’s ability to do its job within the cell? 7. What examples are given that may arise from sequencing an individual’s genome? 8. How many hospital patients in America are thought to die every year as a result of adverse drug reactions? 9. What is meant by a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and how might these affect gene expression (look closely at your answer to question 6)? 10. What percentage of the human genome is thought to have SNPs? UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 3 PERSONAL GENOMICS If you have time look at the website http://www.actionbioscience.org/genomic/barash.html to find out more about some of the ethical issues. 4 UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 PERSONAL GENOMICS Information card What is pharmacogenetics? The following information was taken from the Wellcome Trust website. http://genome.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTD020884.html Genetic variability among humans has an obvious impact on features such as height, hair colour and appearance, but also has an unseen role in our susceptibility to disease and the way in which our bodies metabolise drugs. This last area of study – termed pharmacogenetics – brings together the study of how drugs work in the body (pharmacology) and genetics. Understanding how genes can influence the response to drugs can help explain why some patients respond well to drugs and others do not. It can also help doctors understand why some patients require higher or lower doses of a particular drug. The goal of pharmacogenetics research is to provide information for ‘personalised medicine’, ie giving a patient the right medicine at the right dose. A great deal of pharmacogenetics research has focused on the mechanisms that determine drug concentration within the body, looking at the end result of the ingestion, absorption, metabolism, clearance and excretion of a drug. Genetic tests are being developed to determine a patient ’s ability to metabolise a particular drug, which will allow dosage to be determined with greater certainty, and also to determine which patients may be susceptibl e to adverse side effects as a result of being prescribed a drug. The pharmacological consequences of genetic variation are highly diverse. In some cases a patient may break down or convert a drug slightly more quickly, or slightly slower, than another. But in other cases the absence of drugmetabolising enzymes can cause excessive, and fatal, drug action, or the therapy may fail because the drug is not activated. Remember, gene expression is the transcription of DNA, which will lead to protein synthesis from a mRNA transcript. It is the functional protein within the cell that leads to the correct physiological conditions being maintained. The protein, usually an enzyme, will only be fully fun ctional if it has the correct three-dimensional shape. Mutations may occur in gene regulatory sequences, post -transcriptional RNA processing sites, which may affect the removal of introns (RNA splicing), the UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 5 PERSONAL GENOMICS open reading frame, which would affect the amino acid sequence, and posttranslational protein modification, such as protein folding or carbohydrate conjugation (glycosylation). The scope for error is complex and it is hope d that determining an individual’s genomic sequence may lead to advanced screening for disease; better, safer medicines, more accurate methods of prescribing drug doses, the discovery of new drugs, better vaccines and even reduced overall costs. In America adverse drug reactions are thought to kill up to 100 000 hospital patients a year with over two million serious but non -fatal reactions (http://www.actionbioscience.org/genomic/barash.html ). Many of these problems are thought to be due to single nucleotide polymorphisms (single base substitutions), so collecting and analysing individual sequence data will become increasingly important. An offshoot of the human genome project is the 1000 genome project , which aims to sequence 2500 samples from 27 populations over the next two years. The variation between individual humans is t hought to be about three million bases (one in every thousand) out of the total of three billion bases. 6 UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 PERSONAL GENOMICS What if I couldn’t get insurance cover because of my genetics? I may even lose my job! What if my DNA sequence was different but it turned out to be a neutral mutation? If I knew I had a genetic problem it might put me off having children. I’d rather not know if I have a genetic anomaly or disease. UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 7 PERSONAL GENOMICS If I knew what the problem was likely to be I could plan ahead and make the most of my time. What if I was a minority case and the drug companies didn’t think it worthwhile investing in finetuning my treatment? By knowing my exact genetics they could tailor-make drugs with minimal side effects. Just because my DNA sequence may be slightly different doesn’t mean I will develop symptoms. 8 UNIT 1, PART (III) GENOME (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 By getting the right treatment I would be able to lead a completely normal life.