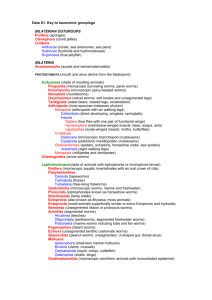

vietnamese bait worms - University of Delaware

advertisement

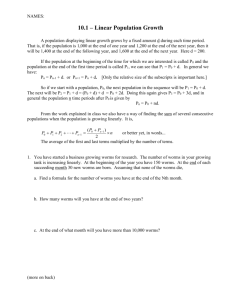

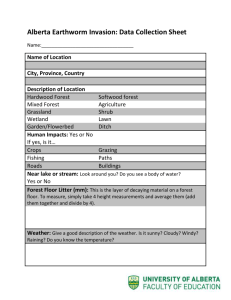

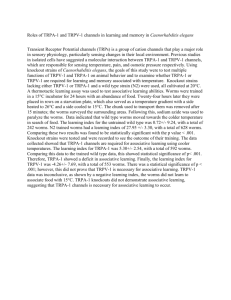

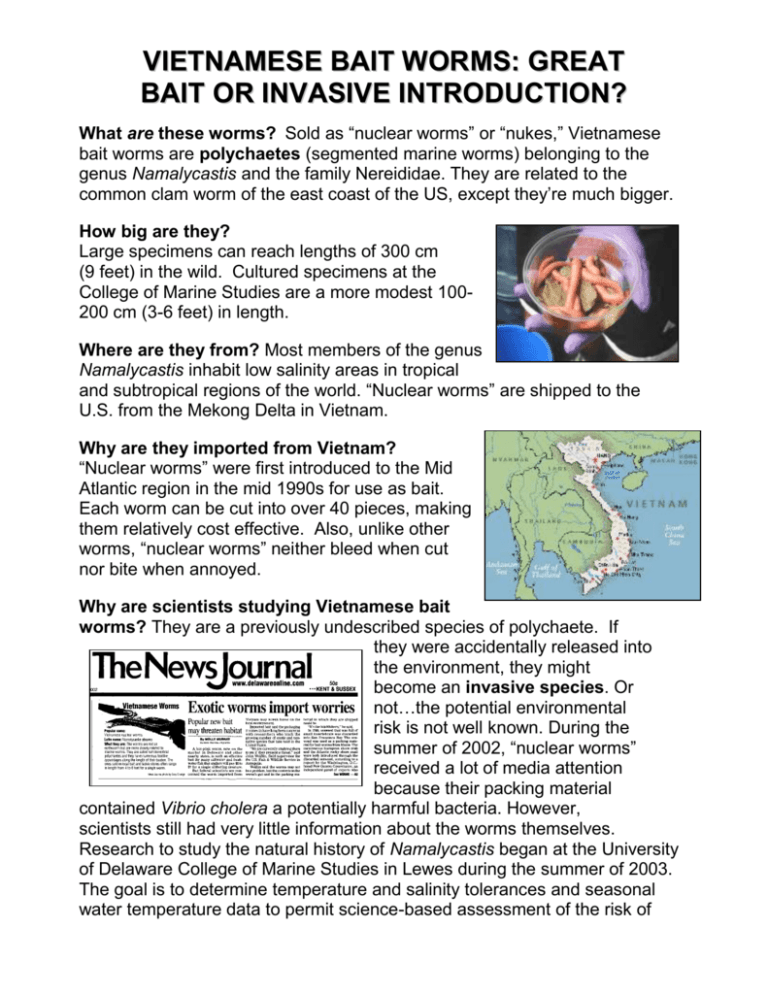

VIETNAMESE BAIT WORMS: GREAT BAIT OR INVASIVE INTRODUCTION? What are these worms? Sold as “nuclear worms” or “nukes,” Vietnamese bait worms are polychaetes (segmented marine worms) belonging to the genus Namalycastis and the family Nereididae. They are related to the common clam worm of the east coast of the US, except they’re much bigger. How big are they? Large specimens can reach lengths of 300 cm (9 feet) in the wild. Cultured specimens at the College of Marine Studies are a more modest 100200 cm (3-6 feet) in length. Where are they from? Most members of the genus Namalycastis inhabit low salinity areas in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. “Nuclear worms” are shipped to the U.S. from the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. Why are they imported from Vietnam? “Nuclear worms” were first introduced to the Mid Atlantic region in the mid 1990s for use as bait. Each worm can be cut into over 40 pieces, making them relatively cost effective. Also, unlike other worms, “nuclear worms” neither bleed when cut nor bite when annoyed. Why are scientists studying Vietnamese bait worms? They are a previously undescribed species of polychaete. If they were accidentally released into the environment, they might become an invasive species. Or not…the potential environmental risk is not well known. During the summer of 2002, “nuclear worms” received a lot of media attention because their packing material contained Vibrio cholera a potentially harmful bacteria. However, scientists still had very little information about the worms themselves. Research to study the natural history of Namalycastis began at the University of Delaware College of Marine Studies in Lewes during the summer of 2003. The goal is to determine temperature and salinity tolerances and seasonal water temperature data to permit science-based assessment of the risk of establishment of this species in Delaware and points south along the US east coast Where they live and what they eat Vietnamese bait worms do quite well under laboratory under conditions simulating local salt marshes. In culture, they inhabit shallow burrows in mud underneath decaying vegetation. They appear to be tolerant of low oxygen (hypoxic) conditions, although like all marine invertebrates, they respire aerobically and are poisoned by high levels of hydrogen sulfide. Fecal pellet analyses suggest that nuclear worms are nonselective deposit feeders and will ingest anything they can fit into their mouths, including sediment, seaweed and cellulose fiber. Temperature limits “Nuclear worms” like it hot. They thrive at 30-35 °C (88-96 °F) and 90-100% relative humidity—in a word, tropical conditions. Interestingly, however, nuclear worms can survive to near 12 °C (mid-low 50’s °F) if they are slowly acclimated to dropping temperatures. Salinity tolerance “Nuclear worms” are remarkably tolerant of a wide range of salinities, from nearly fresh water to fullstrength seawater. They are termed “euryhaline” and adapt to changing salinity by absorbing or releasing water from their body fluids. Great bait or introduction of an invasive species? Judging by their sales at local shops, “nukes” are a popular live bait. Because they require tropical temperatures, it is generally thought unlikely that this species could over winter in the Mid Atlantic region and become established and there is no indication that they would become a pest species. To provide scientific support for these assertions, laboratory experiments are continuing to delimit which areas of the Southeast US coast might be susceptible. During summer 2004, additional experiments are planned to study their survival when cut for bait, their ability to regenerate, their live prey diet and any potential impact on other local species. This research is supported by the Aquatic Nuisance Species Research and Outreach program of the National Sea Grant Office. For additional information contact Dr. Doug Miller 302.645.4277 <dmiller@udel.edu> or John Ewart, 302.645.4060 <ewart@udel.edu>