Course Design Workshop - HEDC

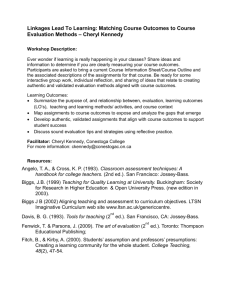

advertisement