Climate change

advertisement

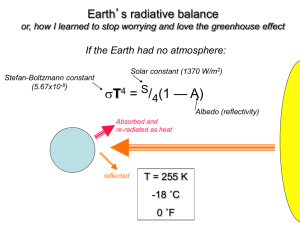

Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future © UNESCO 2010 MODULE 19: CLIMATE CHANGE INTRODUCTION I feel strongly that young people should be given the chance to understand climate change as soon as possible. This will help them deal not only with the immediate challenges facing us, but the longer term ones. It will, for example, assist them in making career choices, for some businesses will expand greatly while others will decline. It will also assist them with consumer choices, because as their understanding of climate change grows, individuals will develop new attitudes about what is appropriate and moral. Young people may even grow up in a world where the relationships between nations will shift. This may occur in part because the tropical rainforests offer a great way of drawing carbon pollution from the air, so the poorest farmers on our planet may become crucial partners to the wealthy nations as they seek to stabilise their climate. One of the most exciting, and immediately relevant, opportunities for young people concerns the new technologies for generating electricity, and providing transport without creating greenhouse gas pollution. In coming decades, these vital tools for stabilising our climate will be develop and brought to market by today’s school children. And tomorrow’s economists will struggle with issues that are new to us. An entire new global market – a trade in will be established, which will have broad implications for many aspects of our lives. For all of these reasons, I believe that the study of climate change is relevant to a great many of the subjects our children undertake, and that by increasing their understanding of the issue they will see the relevance of such disciplines anew. Indeed, as their understanding of the issue develops I believe that they will start seeing the world in a new way, a way that most of us have not possessed. That may seem like a large claim, but as we move to address climate change, so many aspects of our world will alter that it will be little short of a revolution. Source: Adapted from Flannery, T. (2007) Foreword, Thinking about Climate Change: A Guide for Teachers and Students. Climate change is a centrally important issue – not just for politicians but also for teachers. This module provides resources for teachers so that they can feel confident in their knowledge of climate change science and the impacts of the climate crisis and plan interesting and relevant lessons for their students. OBJECTIVES To understand basic concepts, trends and issues in climate change science; To understand the complementary nature of climate change mitigation and adaptation and the major strategies used in each; To appreciate the ethical dimensions of climate change processes and their impacts; and To identify the educational implications of teaching about climate change. ACTIVITIES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. “Get the facts on the world’s hottest topic” Climate change FAQ Impacts of climate change Climate change is an ethical issue Responding to the challenge of climate change Taking action Reflection REFERENCES Baer, H. and Singer, M. (2009) Global Warming and the Political Ecology of Health, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, California. Doucet, C. (2007) Urban Meltdown: Cities, Climate Change and Politics as Usual, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island BC. Dow, K. and Downing, T. (2006) The Atlas of Climate Change: Mapping the World’s Greatest Challenge, University of California Press, Berkeley. Dressler, A. (2006) The Science and Politics of Global Climate Change: A Guide to the Debate, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Flannery, T. (2005) The Weather Makers: How Man is Changing the Climate and What It Means for Life on Earth, Atlantic Monthly Press NY. Gore, A. (2006) An Inconvenient Truth: The Planetary Emergency of Global Warming and What We Can Do About It, Rodale Press, Emmaus PA. Hamilton, C. (2010) Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth About Climate Change, Earthscan, London. Hansen, J. (2010) Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth about the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity, Bloomsbury, New York. Henson, R. (2008) The Gough Guide to Climate Change: The Symptoms, The Science, The Solutions, Rough Guides, London. Holper, P. and Torok, S. (2008) Climate Change: What You Can do about It at Work, at Home, at School, Pan Macmillan, Sydney. Hulme, M. (2009) Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Hopkins, R. (2008) The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience, Green Books, Totnes, Devon. Johansen, B. (2006) Global Warming in the Twenty-First Century, Praeger Publishers, Westport CT. Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril: A Popular Guide to the Latest IPCC Reports, GRIDArendal and SMI Books, Arendal. Lovelock, J. (2006) The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate in Crisis and the Fate of Humanity, Basic Books, New York. Monbiot, G. (2006) Heat: How to Stop the Planet Burning, Allen Lane, London. Moser, S. and Dilling, L. (eds) (2007) Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Pearce, F. (2007) With Speed and Violence: Why Scientists Fear Tipping Points in Climate Change, Beacon Press, Boston. Stern, N. (2006) The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. UNEP/GRID-Arendal (2008) Climate in Peril United Nations Development Programme (2007) Fighting Climate Change: Human Solidarity in a Divided World: Human Development Report 2007-2008, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK. Worldwatch Institute (2009) State of the World 2009: Into a Warming World. INTERNET SITES International Organsisations United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) OECD Climate Change site United Nations Environment Progamme – Climate change site Child rights and climate change State of World Population 2009 - Climate Change and Women Research Organisations World Climate Research Programme World Meteorological Organization Atmospheric Research and Environment Programme World Health Organization (WHO) Programme on Global Change and Health CICERO – Center for International Climate and Environmental Research IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme Germany – the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research Tyndall Centre – United Kingdom’s leading research centre on climate change Business organisations International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Environment and Sustainable Development page Global Climate Coalition The European Business Council for a Sustainable Energy Future EuroACE Environmental advocacy organisations Climate Action Network (CAN) Greenpeace International Homepage World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Climate Change Campaign Health & Environment Alliance (HEAL) Climate Change: Resources from Oxfam Education Sandwatch Manual – Adapting to Climate Change and Educating for Sustainable Development CO2nnect – CO2 on the way to school The Carbon Game Independent organisations Pew Center on Global Climate Change Greenfacts RealClimate – Climate Science commentary web site Climate Ark – Climate change and global warming portal World Resources Institute – Climate change site David Suzuki Foundation – Climate change site Copenhagen Diagnosis: Climate Science Report CREDITS This module was written for UNESCO by John Fien. The production of this module was funded by the Japanese Funds-in-Trust. ACTIVITY 1: “GET THE FACTS ON THE WORLD’S HOTTEST TOPIC” Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. A recent exhibition on climate change at the Birch Aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego ,USA, used the headline: “Feeling the Heat: The Climate Challenge – Get the facts on the world’s hottest topic” to attract visitors to study the exhibition panels. This activity is designed to provide the facts on climate change science as they are currently understood by the world’s best scientists. Consider the following statement about climate change from the Nautilus Institute on Security and Sustainability: Earth is facing a climate catastrophe caused by human action. Scientifically, there is no longer any doubt that pollutants from the combustion of fossil fuels and other human activities are accumulating in the atmosphere, trapping radiation, and raising temperatures. There remains some uncertainty about the precise timing and magnitude of the warming, and about the impacts that will result from it, but this is due as much to uncertainties about how we, as humans, respond to the problem as to scientific uncertainties. Many types of impact are predictable and some are likely already under way: rising temperatures, changes in rainfall levels and seasonality; increased incidence of extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and hurricanes; sea level rise; the melting of polar ice and glaciers. The ecological and human impacts resulting from these changes are expected to include desertification, loss of tropical forests and coral reefs, declines in agricultural productivity, extinction of species, water shortages, growing casualties from natural disasters, and the spread of tropical diseases. Whether the scale of these impacts brings just a further decline in environmental quality and social well-being or leads to a truly catastrophic collapse that leads to starvation, massive migration, and resource wars, will depend on human action during the next several decades, and on the possibility of unanticipated response in the climate system to increasing temperatures and greenhouse gas concentrations. Source: Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability. Q1: Researchers in the Nautilus Institute tried hard in this statement to distinguish between certain and uncertain scientific claims about climate change. Use your learning journal to identify the claims that science is certain about. Check the accuracy of your answer by referring to the lists of certainties and uncertainties about climate change identified in the 2007 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations’ scientific body researching climate change. TEACHING ABOUT CERTAINTY AND UNCERTAINTY A concern of many teachers on matters of climate change is a lack of confidence – both in having the knowledge they need to plan appropriate learning experiences for students and in being able to distinguish between scientific certainties and unproven claims. This is especially the case when so much climate science is based upon the interpretation of trends and complex modeling of the climate system. Some teaches believe that student respect rests on their projecting an image of being “all knowing”. When faced with the task of teaching a topic as important but complex as climate change, such feelings can be a real constraint. A key to overcoming this problem is to be found in the certain knowledge that on any subject there is always more information than any one person can grasp. Climate change is a subject on which even specialists have much to learn. However, it is also a subject upon which much information is readily available as seen by the long list of books and internet sites in the references section of this module. Climate change is also a subject upon which everyone has some knowledge and can contribute to a total understanding. We can help ourselves and our students by establishing mutual respect and a setting for mutual learning by discussing the problems of scientific certainty and uncertainty openly. Such a setting is also an ideal place for assessing the importance of taking precautionary action under conditions of uncertainty. Activity 4 in Module 4 focused upon the objectives of Education for Sustainable Development. Seven objectives were analysed there. The seventh was “Appreciation of uncertainty and precaution”. You can analyse the educational advantages of working with students towards this objective in this diamond-ranking exercise. Q2: Identify five other subjects you might teach in Education for Sustainable Development where there are also opportunities to achieve the educational benefits of working with students about uncertainty and precaution. A quick review of other modules in the Contemporary Issues section of Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future might help here. ACTIVITY 2: CLIMATE CHANGE FAQ Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. A lot of different terms are used in discussions about climate change. Some of these include: Global warming Greenhouse effect Natural Greenhouse Effect Enhanced Greenhouse Effect In fact, in his book and film, An Inconvenient Truth, former US Vice President Al Gore argued that the situation is so severe that terms such as these and climate change are so neutral that they do not encapsulate the urgency of the “planetary emergency” we are facing. Mr Gore suggested that we use the term, “Climate Crisis”. A SIMPLE OVERVIEW Whatever terms you prefer to use, they all refer to the fact that carbon dioxide and other gases in Earth’s atmosphere act like a greenhouse moderating the temperatures we experience. These warm the surface of the planet naturally by trapping solar heat in the atmosphere. This is a good thing because it keeps our planet habitable. However, by burning fossil fuels such as coal, gas and oil and clearing forests we have dramatically increased the amount of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere and temperatures are rising. This is called the “enhanced Greenhouse Effect”. Source: What is Climate Change? A colourless and odourless gas formed from one carbon and two oxygen atoms, CO₂ makes up around three parts per 10,000, or 0.03%, of Earth’s atmosphere. This is a very small amount but it plays a critical role in maintaining the atmospheric balance necessary to all life. By contrast, the atmosphere of “dead planets” such as Venus and Mars is made up mostly of CO₂. The CO₂ produced by plants has been central in keeping Earth’s surface temperature at an average 14°C for the past 10,000 years, which is very habitable for the plants, animals and human activities we know today. This is called the “natural Greenhouse Effect” Much of the rock, soil, animal, plant and water life on Earth is made up of carbon, very much of it stored for millions of years under the ground or ocean in fossilized form from decayed animal and plant matter. When this is extracted and burned – as a fossil fuel – such as oil, gas and coal, carbon escapes into the atmosphere where it combines with oxygen to form CO₂. This means that CO₂ is a waste product – or pollution – every time we burn fossil fuels to make gas or electricity for heating, light and cooking or use petrol to drive a car – and it stays in the atmosphere for about 100 years. As a result, the proportion of CO₂ in the atmosphere is rapidly increasing, causing Earth to warm. This is causing average temperatures to rise, which is resulting in more frequent extreme weather events, long-term droughts, melting polar ice caps and glaciers and rising sea-levels. The relationship between rising temperatures and sea-levels over the past 100 plus years may be seen in the following diagrams. Source: Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril, UNEP/GRID-Arendal and SMI Books, pp. 8-9. Earth’s surface temperatures rose by about 0.6°C over the 20th century. The most recent predictions from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are that the average global surface temperature will continue to rise – and could potentially reach 6.4°C above 1990 levels by 2100 unless immediate action is taken. At that temperature human society as we understand it would no longer exist. From concentrations of just 0.028% CO₂ in the atmosphere in pre-industrial 1750, CO₂ concentrations have risen to 0.043% today. Until recently it was believed stabilising CO₂ in the atmosphere at around 0.055% by 2035 could limit warming by 2°C. However, now 3°C is more likely, causing major impacts on human settlements, coral reefs, rain forests and the polar ice-caps. Urgent international action is needed to limit temperature rises to 2°C, and that means controlling CO₂ levels to 0.045%. This could be a reality by 2020 if governments are able to agree on cooperative national and international action. MORE COMPLEX QUESTIONS Beyond such a simple overview, there are many complex questions about climate change you might want answered. Listed below are a number of questions commonly addressed to climate scientists. The answers are provided by Working Group I of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). What factors determine Earth’s climate? What is the relationship between climate change and weather? What is the greenhouse effect? How do human activities contribute to climate change and how do they compare with natural influences? 5. How are temperatures on earth changing? 6. How is precipitation changing? 7. Has there been a change in extreme events like heat waves, droughts, floods and hurricanes? 8. Is the amount of snow and ice on the earth decreasing? 9. Is sea level rising? 10. What caused the ice ages and other important climate changes before the industrial era? 11. Is the current climate change unusual compared to earlier changes in Earth’s history? 12. Are the increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases during the industrial era caused by human activities? 13. How reliable are the models used to make projections of future climate change? 14. Can individual extreme events be explained by greenhouse warming? 15. Can the warming of the 20th century be explained by natural variability? 16. Are extreme events, like heat waves, droughts or floods, expected to change as the Earth’s climate changes? 17. How likely are major or abrupt climate changes, such as loss of ice sheets or changes in global ocean circulation? 18. If emissions of greenhouse gases are reduced, how quickly do their concentrations in the atmosphere de¬crease? 19. Do projected changes in climate vary from region to region? 1. 2. 3. 4. Source: IPCC (2007) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. The answers from the IPCC to these questions are quite detailed – probably too detailed for most students. Select five questions that your students have asked you – or might ask you – and write a summary of the answer that you would give to your class. Read the latest scientific updates on the causes, impacts and solutions to climate change published by the Union for Concerned Scientists. ACTIVITY 3: IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. The 2007 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) left no doubt that global warming is occurring and that climate change is human-induced. The IPCC concluded that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal” and, for the first time, stated that it was 90% certain that it was caused by the effects of human activities on Earth since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s in Europe and later in North America. And it is increasingly clear that these rising temperatures are having significant impacts on the world already and that many more are likely. Read about the impacts climate change is already having in different countries around the world. Source: Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril, UNEP/GRID-Arendal and SMI Books, pp. 32-38. A map launched at the Science Museum in London has been developed using the latest peer-reviewed science from the British Met Office and other leading impact scientists. It shows that the land will heat up more quickly than the sea, and high latitudes, particularly the Arctic, will have larger temperature increases. Examine the impacts of climate change predicted for different continental regions of the world: Q3: Africa Asia Europe North America Latin and South America Australia and New Zealand How severely will climate change affect your country or region? These many examples show that there are two levels of impacts from climate change. The first level include the impacts of rising temperatures on the physical environment, such as: Glaciers melting faster than predicted The flow of ice from glaciers in Greenland has more than doubled over the past decade. The Arctic ice caps are meeting so fast that a sea passage between north America and Russia has almost formed in recent summer Global sea levels rises, especially in low lying river deltas and small island states The number of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes has almost doubled in the last 30 years Nearly 300 species of plants and animals are moving closer to the poles Heat waves are becoming more frequent and more intense Droughts and wildfires are occurring more often. However, because we depend upon the physical environment for all the resources we need – water, food, clothing, shelter, manufactured goods, transport, energy, jobs, recreation, etc. – these primary impacts cascade into a second level where they impact on the resources we need such as: Water – including drought, water quality, water supplies Food – including cropping and livestock sectors Ecosystems – including national reserves, species diversity, and natural and plantation forests Coasts – including fisheries, marine life, coastal infrastructure Health – including heat stress, vector borne diseases Settlements – including infrastructure, local government, planning, transport, energy, emergency services The 2007 IPCC report summarized the extent of these impacts under conditions of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5°C temperature increases. [Click image for full size] Source: Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril, UNEP/GRID-Arendal and SMI Books, pp. 32-38. IMPACTS IN THE AMAZON The long-term impacts of climate change – such as those in the table – can seem abstract unless they are grounded in case studies of real places and people. Here we take the Amazon region as an example. The Amazon rainforest is a critical influence on South American climate and one of the world’s most important carbon banks. It covers almost as much land as China, Australia or the United States, and is home to 20% of all the world’s plant and animal species. The rainforest also plays a crucial role in the water cycle of South America and pumps oxygen into the atmosphere, earning it the nickname, the “Lungs of the World”. Climate scientists predict a significant dieback of the Amazon rainforest by 2050 and predict that the area will have larger losses of soil and plant carbon than of any other place on Earth by the end of the 21st century. This shrinking of the Amazon rainforest is a major reason why scientists predict the vegetation of the Amazon rainforest will shift from being a “carbon sink” to a major source of carbon by 2050. Read about the predicted impacts of small temperature increases on the rain forests of the Amazon. Read about the impacts of climate change on the strategies that the Shipibo people of the Peruvian Amazon traditionally use to cope with the severe floods of their tributary of the Amazon. Q4: What advice would you give the governments of the Amazon region about how to minimize the impacts of increased temperatures on the rainforest? Q5: What advice would you give the Shipibo people about adapting to the changed climatic conditions along the River? IMPACTS IN YOUR COMMUNITY Q6: In what ways is your community experiencing the impacts of climate change? Q7: Which of the nine impacts is the most likely to affect your local community? Why? Q8: Which of the nine impacts is least likely to affect your local community? Why? Q9: Who do you think will be most affected by this impact? Why? Q10: What options are being explored in your community to try to adapt to these environmental changes? ACTIVITY 4: CLIMATE CHANGE IS AN ETHICAL ISSUE Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. When we were looking at the impacts of climate change in Activity 3, we saw that the long-term impacts of climate change can seem abstract unless they are grounded in case studies of real places and people. So, we then conducted a case study of the impacts in the Amazon region as an example. This helped us to see the details, especially when we then examined climate change impacts in our local communities. This helped us to see that climate change is not just a scientific issue – or a political one for governments to solve. Climate change is an ethical issue too because climate disasters hit the poorest people of the world the most. This activity examines the arguments that have been made for this by three international bodies: the Commonwealth Foundation, the World Bank and the Association of Small Island States. THE COMMONWEALTH FOUNDATION In a speech to the 2007 Commonwealth Youth Forum in Kampala, the Director of the Commonwealth Foundation, Mark Collins said that climate change was the most important issue facing the world. In fact, he said, “If the Millennium Development Goals were being written today, tackling climate change would be top of the list”. We are now past the halfway stage towards the 2015 target for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) but performance is falling behind, at least partly because environmental sustainability is not being addressed adequately. Unless we can control deforestation, protect biodiversity, ensure water supplies and address the [carbon] pollution that causes climate change, poverty will always stalk the world. These should not be seen as narrowly-defined environmental problems. Climate change in particular is an economic and humanitarian problem. Source: Collins, M. (2008) Climate Change: A Priority Issue for the Commonwealth. Q11. The Commonwealth Foundation identified two ethical arguments about climate change: Climate change is a major cause of poverty The cost of addressing climate change will slow progress towards Millennium Development Goals in many poorer countries. Identify passages in the text that relate to these concerns. THE WORLD BANK The World Bank argues that the development implications of climate change for the poorest countries in the world are very significant. This is because developing countries are more vulnerable to the increased impacts of extreme weather events (i.e., floods, droughts and storms) and other changes than rich countries. For example, climate change is expected to (among other things): increase climate variability and hurt agricultural productivity throughout the tropics and sub-tropics (threatening food security) further decrease water quantity and quality in most arid and semi-arid regions (where poor communities depend on rainfall for their crops and drinking water) increase the incidence of malaria, dengue fever and other vector-borne diseases in the tropics and sub-tropics (where health services are already weak death tolls would rise) harm ecological systems and their biodiversity (that will provide fewer services, livelihoods and income possibilities to communities and societies) raise sea levels and displace tens of millions of people in low-lying areas, such as the Ganges, Mekong, Red and Nile river deltas (threatening the very existence of many cities and even some small island states. Responses to climate change in developed countries may also increase prices for energy, food, and other commodities, making these items more expensive for developing countries. In some cases, the adoption of carbon neutral technologies may need to be accelerated despite the higher commercial costs and risks. The emerging and yet incomplete cost estimates of additional investments needed in developing countries are likely to cost hundreds of billions of dollars a year for several decades. Needing to find such resources may make achieving the Millennium Development Goals even more difficult in many developing countries. Thus, many hard-earned development gains could be lost because of climate change, leaving more people in poverty and possibly pushing still more there also. The poorest communities and countries have contributed least to the problem but will be affected worst. Source: Adapted from World Bank. Q12. Identify five ethical issues in the World Bank’s concerns about climate change and development. Quote passages in the text to support these concerns. ASSOCIATION OF SMALL ISLAND STATES The ethical basis of climate change is central to the international advocacy work of the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS). AOSIS is a coalition of small island and low-lying coastal countries that share similar development challenges and concerns about the environment, especially their vulnerability to climate change. AOSIS has a membership of 43 States and observers, drawn from all oceans and regions of the world: Africa, Caribbean, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean, Pacific and South China Sea. Thirty-seven are members of the United Nations and make up 20% of the UN’s membership. Together, they are close to 28% of all the developing countries in the world and are home to five percent of the world’s population. AOSIS would like to be seen as the conscience of the international community on climate policy because of what it sees as the truth and justness of its cause. AOSIS believes that island countries should have a central role in international climate negotiations because they face the greatest risks from climate change. Otherwise, it claims, AOSIS countries face “destruction without representation”. The principle of representation proportionate to risk is one that AOSIS. According to the Ambassador for St. Lucia in the Caribbean, If even a decade passes before beginning the process of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, we will be forced either to make far more drastic cuts later, or to incur unacceptable damage to the global climate system. If we wait for the proof, the proof will kill us. Source: AOSIS (2000) Climate Change and Small Island States. Q13. Identify three ethical issues in the AOSIS concerns about climate change and development. Quote passages in the text to support these concerns. Q14: Explain the ethical issue about climate change in this graph. Source: New Internationalist, No. 419, 2009. Q15: How do these examples of ethical issues compare with the triple injustice of climate change identified by New Internationalist magazine? Q16: What are the major ethical issues about climate change in your country? To what extent are they similar or different from the ones identified in this activity? Why? ACTIVITY 5: RESPONDING TO THE CHALLENGE OF CLIMATE CHANGE Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. The threats posed by climate change make it a matter of extreme urgency that we take action, immediately to limit the effects and, in the longer term, to adapt to the changes that are sure to come. This is perhaps the defining challenge of our age but it human will-power, decisions and action – as individuals, businesses, cities and governments – that will determine just how serious the problem will become. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has prepared a guide for responding to the challenges of climate change called Kick the Habit: A UN Guide to Climate Neutrality. It is available as a PDF download or an interactive e-book. There is also a pre-prepared Powerpoint presentation. Together, these provide a rich guide to strategies for advancing the transition to a carbon neutral world.. The two major strategies for responding to the challenge of climate change are called mitigation and adaptation. These are distinct – but complementary – strategies, and both are needed for an effective response to climate change. MITIGATION Climate mitigation involves actions that seek to permanently eliminate or reduce the long-term risk and hazards of climate change to human life, ecosystems or property. The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines mitigation as: An anthropogenic (human) intervention to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases. Mitigation tackles the causes of climate change by reducing the amount of CO₂ emitted into the atmosphere. That is, it refers to all the actions we can take to reduce the burning of fossil fuels – and includes strategies for reducing energy usage, increasing energy efficiency replacing fossil fuels by other energy sources and trapping CO₂ and other greenhouse gases under the ground, in the soil or in plants. This table is a list of strategies for achieving mitigation goals that are available today and expected to be available by 2030. [Click for full size] See the IPCC page on climate change mitigation for more details. ADAPTATION Adaptation refers to the ability of a system to adjust to climate change in order to moderate potential damage, to cope with the consequences, or to take advantage of opportunities. The IPCC defines adaptation as: …the adjustment in natural or human systems to a new or changing environment. Adaptation to climate change refers to adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities. Climate adaptation tackles the effects of climate change by minimising its impacts. That is, it refers to all the actions we can take to prevent or offset damage to ecosystems, agriculture, coastal areas, urban infrastructure and human health. Some examples of adaptation strategies include: Water: increased rainwater harvesting, water storage and conservation, water re-use, desalination, greater efficiency in water use and irrigation Agriculture: altering planting dates and crop varieties, relocating crops, better land management (for example erosion control and soil protection by planting trees) Infrastructure: relocating people, building seawalls and storm surge barriers, reinforcing dunes, creating marshes and wetlands as buffers against sea level rise and floods Human health: action plans to cope with threats from extreme heat, emergency medical services, better climate-sensitive disease surveillance and control, safe water and improved sanitation Tourism: diversifying attractions and revenues, moving ski slopes to higher altitudes, artificial snow-making Transport: realigning and relocating routes, designing roads, railways and other transport equipment to cope with warming and drainage Energy: strengthening overhead transmission and distribution networks, putting some cabling underground, energy efficiency and renewable energy, reduced dependence on single energy sources. See the IPCC page on climate change adaptation. Q17: Mitigation seeks to reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere but adaptation seeks to help us reduce the effects of carbon in the atmosphere. Which approach do you think is the most important? Why? COMPLEMENTARY APPROACHES Neither mitigation (reducing the potential impacts by slowing down the process itself) nor adaptation to climate change (reducing the potential impacts by changing the circumstances so that they strike less hard) alone can avoid all climate change impacts. However, together they can significantly reduce the risks of climate change. In general the more mitigation we can achieve, the less will be the impacts to which we will have to adapt, and the less the risks for which we will have to try and prepare. Conversely, the greater the degree of preparatory adaptation we make, the less may be the impacts associated with any given degree of climate change. Thus, climate mitigation and adaptation should not be seen as alternatives to each other, as they are not discrete activities but rather a combined set of actions in an overall strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. THE URGENCY OF ACTION In 2006, the UK government published the Stern Report on the economics of climate change. Named after the prime author, Nicolas Stern (now Lord Stern) who worked for the Treasury, the report is the world’s biggest ever economic evaluation of climate change. The Stern Report found that the cost of global warming and its effects would be over US$9 trillion – a bill greater than the combined cost of the two World Wars and the Great Depression – if immediate action was not taken. Even if the world stopped all carbon pollution today, much of this cost would be unavoidable because the long term effects of carbon already in the atmosphere means continued climate change for another 30 years, with sea levels continuing to rise for a century. The actions recommended include: 1. Global emissions must fall by at least 50% relative to 1990 levels by 2050, in order to limit the grave risks associated with severe climate change. This will require concerted collaborative action with little scope for any large group of people to depart significantly the target 2. Developed countries – who produced the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere over the past century – must take on immediate and binding national targets of 20% to 40% emission reduction by 2020, and to commit to reductions of at least 80% by 2050 3. Successful demonstration by developed countries that they can deliver credible reductions by 2020 – without threatening growth – will drive the design of mechanisms and institutions to transfer funds and technologies to developing countries 4. Subject to this, a formal expectation that developing countries would also be expected to take on binding national targets of their own 20% emissions reduction by 2020 5. Fast growing middle income developing countries with higher incomes must take immediate action in order to stabilise and reverse emissions growth 6. A commitment by all countries, regardless of targets, to develop the institutions, data and monitoring capabilities, and policies to avoid high-GHG infrastructural lock-in. Stern, N. (2008) Key Elements of a Global Deal on Climate Change, London School of Economics, pp. 5-6. Q18: Summarise the actions that Lord Stern believed must be taken by: Developed countries Developing countries Middle income developing countries All countries Significantly, the Stern report predicted that the world would only need to spend one per cent of global GDP, around US$500 billion, to achieve these goals – or roughly what is spent worldwide on advertising each year, and half of what the World Bank estimates would be the cost of a global flu pandemic. Q19: Compare the cost of effective international action on climate change to the cost of fixing other global problems. ACTIVITY 6: TAKING ACTION Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. There is little doubt that the need for action to address climate change is very urgent. Governments, business and industry, communities, households and individuals all have important roles to play. An enormous number of books, websites and brochures from governments and environmental groups telling us what actions we can take to avoid climate change. For example, the end of the book and movie of Al Gore’s, An Inconvenient Truth, provides a list of actions for people to take: 1. Change a light 2. Drive less 3. Recycle more 4. Check your tires 5. Use less hot water 6. Avoid products with a lot of packaging 7. Adjust your thermostat 8. Plant a tree 9. Turn off electronic devices 10. Spread the word Q20: Which of these actions would/do you find (i) relatively easy and (ii) more difficult to take? Why? Q21: It has been argued that the list of actions recommended in An Inconvenient Truth are too individualistic and best suited to people who live in rich developed countries. Do you agree? Why? Q22: If it is true that the actions are too individualistic and best suited to people who live in rich developed countries, why might Al Gore still have developed such a list? An Internet search for the terms <“climate change” + “what you can do”> on 22 March 2009 revealed 16,100 sites in Australia alone and 261,000 worldwide. When “what you can do” in this search was changed to “what governments can do”, Google identified 146 and 2,340 sites, respectively. Substituting “what companies can do” and “what corporations can do” identified a total of only 12 sites in Australia and 1,405 sites worldwide. Q23: Conduct a similar Internet search for your country and identify how many sites are identified. Q24: Compare the results from the Internet search in your country with the results of the search in Australia. Why might there be any similarities or differences? Q25: Why do you think that there are more websites for what individuals can do about climate change than what companies and governments can do? Recognising the importance of what everyone – individuals, families, communities, governments and businesses – can do about climate change led the Worldwatch Institute to identify ten key strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate change. The first of these was lifestyle changes by individuals but the other nine emphasise roles for all sectors of society. The ten strategies are: Changing Lifestyles The assumption that the “good life” requires ever more individual consumption, more meat-eating, ever larger homes and vehicles, and disposable everything will need to fade. A spirit of shared and equitable material sacrifice can replace it – with no loss of the things that really matters, such as active good health, strong communities, and time with family. See the module on Sustainable Communities. Thinking Long-term At the core of the climate problem is the likelihood that future generations will pay with a deteriorating global environment for the refusal of current generations to live in balance with the atmosphere. Visionary leaders will need to marshal the public to take responsibility for the impacts of today’s behavior on the future and to act accordingly. Sustainability means learning how to think in terms of forever. Innovation The emissions shift will require technologies that break the carbon link to energy consumption with as little sacrifice of price and convenience as possible. A range of renewable technologies can produce electricity and meet heating and cooling needs. Such technologies include buildings that produce more energy than they consume and “smart grids” that use information technology to match renewably produced electricity precisely to demand. Population Rarely addressed in the context of climate change, future population trends could make the difference between success and failure in the long-term balance of human activities, atmosphere, and climate. The world’s population is likely to stop growing and then gradually decline for a period when women gain the full capacity to decide for themselves whether and when to have children. See the module on Population and Development. Healing Land Managed for the task, the Earth’s soil and vegetation can remove billions of tons of carbon from the atmosphere. Agricultural landscapes can accomplish this while improving food and fiber production and minimizing the need for artificial fertilizer and fossil-fuel-driven tilling and raising farmer incomes. See the module on Sustainable Agriculture. Strong Institutions The global nature of climate change demands international cooperation and sound governance. The strength and effectiveness of the United Nations, multilateral banks, and major national governments are essential to addressing global climate change. These institutions require strong public support for their critical work. The Equity Imperative No climate agreement will succeed without support from those countries that have so far contributed little to human-induced climate change, have low per- capita emissions, and stand to face the biggest challenges in adapting to the coming changes. Agreements and strategies that are fair to developing and industrialized countries alike are essential. Economic Stability Addressing climate change will demand attention to costs and the promise of improving rather than undermining long-term economic prospects. A climate agreement will have to operate effectively during anemic as well as booming economic periods, facing squarely the challenges of poverty and unemployment while continually reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Political Stability A world beset by conflict and terrorism is far less likely to prevent dangerous climate disruption than one at peace. Security and climate must be addressed simultaneously. Negotiating an effective and fair climate agreement offers countries a needed opportunity to practice peace and re-frame international relations along cooperative rather than competitive lines. Mobilizing for Change The way to deal with climate change we are causing is to see the opportunity for a new global economy and new ways of living in the effort to bring net greenhouse gas emissions to an end. There is no guarantee such a transition will be easy – or even possible. However, local and global movements to make the effort are needed now, and could yield new jobs, new opportunities for peace, and global cooperation beyond what humanity has ever achieved. Source: Worldwatch Institute (2009) State of the World 2009: Into a Warming World. Q26: Categorise the ten strategies into their relevance for individuals, families, communities, governments and businesses. Q27: Identify three of these strategies that you would be able to integrate into your teaching about climate change and other sustainable development topics. Briefly explain how. ACTIVITY 7: REFLECTION Begin by opening your learning journal for this activity. Completing the module: Look back through the activities and tasks to check that you have done them all and to change any that you think you can improve now that you have come to the end of the module. Read UNESCO’s Policy Dialogue on Climate Change and ESD. You will use this document to reflect on the issues of education and climate change that you have studied in this module. Q28: What does UNESCO identify as the four implications for education about climate change? Q29: To what extent do you feel comfortable about being able to teach towards the eight themes identified by UNESCO? These are: Q30: clear distinctions between different scientific concepts and processes associated with climate change; knowledge of, and abilities to distinguish between, certainties, uncertainties, projections and risks associated with climate change; knowledge of the history and interrelated causes of climate change (which include technical, scientific, ecological and social dimensions; economic dimensions; and political dimensions); knowledge of mitigation and adaptation practices that can contribute to wider social transformation towards sustainability, including abilities to participate in such practices; knowledge of consequences and what is being learned about mitigation and adaptation to climate change; good understanding of the time-space dynamics of climate change, including the delayed consequences that current greenhouse gas emissions hold in store for the quality of life, security and development options of future generations; understanding of different interests that shape different responses to climate change (e.g. business interests, consumer interests, farmers’ interests, political interests, future generations’ interests, etc.) and abilities to critically judge the validity of these interests in relation to the public good; and critical media literacy to address the causes of overconsumption and develop capacity to make better lifestyle choices and to participate in climate change solutions. UNESCO suggests that climate change education should be (i) transformative and (ii) practice and solution-centred. Identify the modules in Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future that would provide advice on these two aspects of teaching and learning. UNESCO suggests that schools could conduct a policy dialogue with different stakeholders on various questions about education and climate change. This could a dialogue at the national level of education and/or climate change policy – or it could be at the local school level. Q31: Identify the stakeholder groups you would invite to a policy dialogue on climate change and education in your school community? What goal or outcome would you like from the discussion of each question? Robust Findings Observed changes in climate, their effects and their causes Warming is un ambiguous, as demonstrated by observations such as: o rises in global average air and sea temperatures and average sea levels o widespread melting of snow and ice; Observed changes in many biological and physical systems are consistent with warming: o many natural systems on all continents and oceans are affected; 70% growth of greenhouse gas emissions in terms of the global warming potential between 1970 and 2004; Concentrations of methane (CH₄), carbon dioxide (CO₂) and nitrous oxide (N₂O) are now far higher than their natural range over many thousands of years before industrialization (1750); Most of the warming over the last 50 years is “very likely” to have been caused by anthropogenic increases in greenhouse gases. Causes and projections of future climate changes and their impacts Global GHG emissions will continue to grow over decades unless there are new policies to reduce climate change and to promote sustainable development. Warming of about 0.2°C a decade is projected for the next two decades (several IPCC scenarios). Changes this century would “very likely” be larger than in the 20th. Greater warming over land than sea, and more in the high latitudes of the northern hemisphere. The more the planet warms, the less CO₂ it can absorb naturally. Warming and rising sea levels would continue for centuries, even if GHG emissions were reduced and concentrations stabilized, due to feedbacks and the time-lag between cause and effect. If GHG levels in the atmosphere double compared with pre-industrial levels, it is “very unlikely” that average global temperatures will increase less than 1.5°C compared with that period. Responses to climate change Some planned adaptation to climate change is occurring, but much more is needed to reduce vulnerability. Long term unmitigated climate change will “likely” exceed the capacity of people and the natural world to adapt. Many technologies to mitigate climate change are already available or likely to be so by 2030. But incentives and research are needed to improve performance and cut cost. The economic mitigation potential, at costs from below zero to US$100 per tonne of CO₂ eq, is enough to offset the projected growth of global emissions or to cut them to below their current levels by 2030. Prompt mitigation can buy time to stabilize emissions and to reduce, delay or avoid impacts. Sustainable development and appropriate policy-making in sectors not apparently linked to climate help to stabilize emissions. Delayed emissions reductions increase the risk of more severe climate change impacts. Source: Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril, UNEP/GRID-Arendal and SMI Books, p.6. Key Uncertainties Observed changes in climate, their effects and their causes Limited climate data coverage in some regions. Analysing and monitoring changes in extreme events, for example droughts, tropical cyclones, extreme temperatures and intense precipitation (rain, sleet and snow), is harder than identifying climatic averages, because longer and more detailed records are needed. Difficult to determine the effects of climate change on people and some natural systems, because they may adapt to the changes and because other unconnected causes may be exerting an influence. Hard to be sure, at scales smaller than an entire continent, whether natural or human causes are influencing temperatures because (for example) pollution and changes in land use may be responsible. There is still uncertainty about the scale of CO₂ emissions due to changes in landuse, and the scale of methane emissions from individual sources. Causes and projections of future climate changes and their impacts It is uncertain how much warming will result in the long term from any particular level of GHG concentrations, and therefore, it is uncertain what level – and pace – of emissions cuts will be needed to ensure a specific level of GHG concentrations. Estimates vary widely for the impacts of aerosols and the strength of feedbacks, particularly clouds, heat absorption by the oceans, and the carbon cycle. Possible future changes in the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are a major source of uncertainty about rising sea levels. Projections of climate change impacts beyond about 2050 are heavily dependent on scenarios and models. Responses to climate change Limited understanding of how development planners factor climate into their decisions. Effective adaptation steps are highly specific to different political, financial and geographical circumstances, making it hard to appreciate their limitations and costs. Estimating mitigation costs and potentials depends on assumptions about future socio-economic growth, technological change and consumption patterns. Not enough is known about how policies unrelated to climate will affect emissions. Source: Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril, UNEP/GRID-Arendal and SMI Books, p.7. Main Greenhouse Gases Gas name Water vapour Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Methane (NH₄) Pre-industrial concentration (ppmv*) Concentration in 1998 (ppmv) 1 to 3 1 to 3 280 0.7 365 1.75 Atmospheric Main human lifetime activity source (years) GWP ** A few days - - Variable Fossil fuels, cement production, land use change 1 12 Fossil fuels, rice paddies, waste dumps, livestock 21 310 Nitrous Oxide (N₂O) 0.27 0.31 114 Fertilizers, combustion, industrial processes HFC 23 (CHF₃) 0 0.000014 250 Electronics, refrigerants 12 000 HFC 134a (CF₃CH₂F) 0 0.0000075 13.8 Refrigerants 1 300 HFC 152a (CH₃CHF₂) 0 0,0000005 1.4 Industrial processes 120 0.0004 0.00008 >50 000 Aluminium production 5 700 Perfluoroethane (C₂F₆) 0 0.000003 10 000 Aluminium production 11 900 Sulphur hexafluoride (SF₆) 0 0.0000042 3 200 Dielectric fluid 22 200 Perfluoromethane (CF₄) * ppmv = parts per million by volume ** GWP = Global warming potential (for 100 year time horizon). Source: Kirby, A. (2008) Climate in Peril, UNEP/GRID-Arendal and SMI Books, p.19. Impacts of climate change The Sahel region, which experienced catastrophic drought for decades until rains returned in the 1990s, could now experience wetter weather for decades to come. We saw this recently in the Horn of Africa and northern East Africa where very dry areas, for example in Ethiopia, Northern Kenya and Northern Uganda, experienced floods. In Southern Africa drought, having plagued the region since the 1970s, is projected to intensify further. Part of the reason is that the Indian Ocean has warmed more than 1°C since 1950. As showers and thunderstorms develop in the rising air above the warming ocean, they lead to sinking dry air and ensuing drought in a surrounding ring that includes Southern Africa. In mountainous areas of Eastern Africa the picture is mixed. Warming is gradually causing the melting of the glaciers on Mt Kilimanjaro, adversely affecting the water security of communities in the lowlands below. Meanwhile, mountainous areas like Lesotho are experiencing more extreme and sudden weather events, including heavy snowfall. In Bangladesh a permanent one metre rise in sea level (predicted by 2100) would inundate 17.5% of the country and result in between ten and 30 million environmental refugees. A rise of just half a metre would put six million people at risk of flooding. Storm surges can have similar temporary impact much sooner. One outcome of climate change is a decline in health standards. In India a record 944mm of rainfall in Mumbai in July 2005 claimed over 1,000 lives. Climate change is allowing mosquito-borne diseases like malaria, yellow fever and dengue fever to extend their range, and water-borne diseases like cholera inevitably follow floods, especially where these occur in areas of poor sanitation. Cyclone Nargis ripped across Burma in May 2008 killing an estimated 150,000 and severely affecting 2.4 million. In the Caribbean, coral bleaching, caused by a combination of El Nino and warming seas, will have a serious impact on biodiversity and subsequently tourism. But extreme weather events are the main cause of anxiety. Hurricane Ivan practically destroyed Grenada’s economy in September 2004, and Hurricanes Ivan and Dean seriously impacted Jamaica too. In April 2008, a week of protests and riots in Haiti over rising food prices left at least five people dead and 200 injured. These impacts are likely in the Indian Ocean also. For example, sea level rises and damage to fisheries could be disastrous for the economies of islands like the Seychelles and the Maldives where fisheries and tourism are the biggest earners. For many years now, the response to fewer fish has been bigger trawlers and bigger fleets, but this cannot last. In Guyana, a system of dykes theoretically protects the most productive lands along the coast, which are in fact below sea level. But with rising seas the coastal agriculture is very vulnerable to flooding, storm surges and sea level rise. In recent years, there have been extensive floods in Guyana, and more are likely, leading to severe economic impacts. Climate change is most likely to be the cause of already serious changes in Australia. Australia is in the grip of nearly a decade of drought and breeding stock are being moved to pastures in Tasmania. Bushfires are a constant hazard. Some farmlands are at risk of being permanently abandoned. Suicide rates amongst farmers have risen. In the Carteret Islands off Papua New Guinea, a combination of sea level rise and storm surge has made the islands uninhabitable and they have now been abandoned. Similarly in the Indian Ocean many Maldivian islands are likely to be uninhabitable under current scenarios of sea level rise, although the government is trying to create sea defences around the main islands. Many Pacific Ocean island nations face similar problems with sea level rises. They also depend heavily upon tuna fisheries as their biggest earner. But the behaviour of these migratory fish will certainly change as undersea currents shift. In the USA, Hurricane Katrina hit the US Gulf Coast, leading to the flooding and evacuation of many areas that have yet to be rebuilt. Katrina caused 1,836 deaths also. The 2003 heatwave in Europe killed approximately 35,000 people from nine countries. In summer 2007, Britain suffered widespread flooding following one of the wettest months on record. It caused $4 billion worth of damage and prompted the biggest rescue effort in peacetime Britain. Source: New Internationalist and Commonwealth Foundation. Amazon could shrink by 85% due to climate change, scientists say Scientists say 4°C rise would kill 85% of the Amazon rainforest - Even modest temperature rise would see 20-40% loss within 100 years Global warming will wreck attempts to save the Amazon rainforest, according to a devastating new study that predicts that one-third of its trees will be killed by even modest temperature rises. The research shows that up to 85% of the forest could be lost if greenhouse gas emissions are not brought under control, the experts said. But even under the most optimistic climate change scenarios, the destruction of large parts of the forest is “irreversible”. Vicky Pope from the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office said: “The impacts of climate change on the Amazon are much worse than we thought. As temperatures rise quickly over the coming century the damage to the forest won’t be obvious straight away, but we could be storing up trouble for the future.” Another scientist said: "When I was young I thought chopping down the trees would destroy the forest but now it seems that climate change will deliver the killer blow.” The study used computer models to investigate how the Amazon would respond to future temperature rises. It found that a 2 degree rise above pre-industrial levels, widely considered the best case global warming scenario and the target for ambitious international plans to curb emissions, would still see 20-40% of the Amazon die off within 100 years. A 3 degree rise would see 75% of the forest destroyed by drought over the following century, while a 4 degree rise would kill 85%. Experts had previously predicted that global warming could cause significant “dieback” of the Amazon. Experts predict that higher worldwide temperatures will reduce rainfall in the Amazon region, which will cause widespread local drought. Increased temperatures will bring reduced rainfall, and with less water and tree growth, “homegrown” rainfall produced by the forest will reduce as well, as it depends on water passed into the atmosphere above the forests by the trees. The cycle continues, with even less rain causing more drought, and so on. With no water, the root systems collapse and the trees fall over. The parched forest becomes tinderbox dry and more susceptible to fire, which can spread to destroy the still-healthy patches of forest. Peter Cox, professor of climate system dynamics at the University of Exeter (UK), said the effects would be felt around the world. “Ecologically it would be a catastrophe and it would be taking a huge chance with our own climate. The tropics are drivers of the world’s weather systems and killing the Amazon is likely to change them forever. We don’t know exactly what would happen but we could expect more extreme weather.” Massive Amazon loss would also amplify global warming “significantly” he said. “Destroying the Amazon would also turn what is a significant carbon sink into a significant source.” When the river roars, time to move – but where? Rural and indigenous communities have always lived with environmental variability. Today, traditional strategies to cope with environmental change may offer a foundation for efforts to adapt to global climate change. In some cases, however, these time-tested approaches may be compromised by new and external constraints. The Shipibo are an indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon (South America) whose traditional territories are the alluvial plains of the Ucayali River. While fishing is the mainstay of their livelihood, slash and burn agriculture and gardening provide important complementary resources. Their villages are built on stilts on the banks of the rivers and lakes of the floodplains, benefiting in this way from a wealth of aquatic resources and soils fertilized by seasonal flooding. In response to the dynamics of the Ucayali River, whose channel is continuously shifting, the Shipibo have chosen to be mobile. They move to new locations when the shifting course of the river floods their gardens, making it impossible for crops to grow, and when erosion of the river banks is so severe that it threatens their houses. They prepare themselves for this eventuality by prospecting for future village sites. Important characteristics include the presence of high ground where their houses are less susceptible to flooding, and the proximity of good fishing areas, such as channels connecting lakes to the Ucayali River. To facilitate mobility, the Shipibo build their houses from lightweight materials, for example, roofs of woven from the leaves of the kantsin palm (Scheelea brachyclada) and posts and beams of light wood. The house design allows it to be easily dismantled and re-assembled. Several indicators are used by the Shipibo to forewarn of an impending flood. The waters become dark in colour and the river transports an increasing volume of vegetative debris. The Shipibo also recognise that a deep roaring of the river waters may signal the imminent arrival of a devastating flood, which may rapidly erode shorelines and threaten the village. These traditional strategies that the Shipibo use to prepare for and respond to local environmental change may also help them face the challenges of climate change. According to the Shipibo, the rainy season has become longer and more intensive. This may lead to increased river flow, accelerated erosion and a more rapid displacement of the river channel. Increased mobility represents one possible response. Today, however, suitable and unoccupied village sites are increasingly rare. New actors who have invaded the territory are competing for land and resources. Large areas are being converted to intensive agriculture to provide food for local and national markets. Other parts of the Shipibo territory are lost to State concessions for logging, or oil and gas exploitation. As a result, the traditional adaptation strategy of the Shipibo, their capacity to move village locations in response to environmental change, is now severely constrained. Options to respond and adapt to climate change are diminished. Indeed, in response to a wide range of environmental and social changes, more and more Shipibo are leaving their traditional homelands and moving to cities such as Pucallpa or even Lima, where many remain marginalized. Source: Climate Frontline, 17 October 2008. The Triple Injustice of Climate Change Injustice 1: Climate change is hitting the poorest first and worst. Many hundreds of thousands have already died from the worsening floods, droughts, heat-waves, cyclones and disease that global warming is unleashing. The death-toll is predicted to rise to millions in just a few decades. Nearly all these climate change casualties – and those most at risk – are poor people living in the Majority World. Injustice 2: Those most affected did not cause it and are powerless to stop it. Climate change has been largely created by the burning of fossil fuels by industrialised nations, with the richest being the most culpable planet-cookers. As Panapase Nelisoni, from the Government of Tuvalu – one of the Pacific islandnations currently disappearing beneath the waves due to rising sea-levels – quite rightly points out: ”The industrialised countries caused the problem, but we are suffering the consequences… it is only fair that people in industrialised nations and industries take responsibility for the actions they are causing. It’s the polluter-pays principle: you pollute, you pay.” Injustice 3: The polluters aren’t paying. In fact, greenhouse gas emissions – of which carbon dioxide accounts for 80% of warming, the others being methane, nitrous oxide and certain industrial gases – continue to rise in developed countries, despite their signing the Kyoto Protocol which was supposed to reduce them. Kyoto was also supposed to lead to financial support for poor countries like Tuvalu struggling at the sharp end of the climate crisis, but the international community has shown little interest. The G8 have so far pledged a shockingly inadequate $6 billion – to be disbursed through World Bank loans, forcing affected countries to pay twice for their own suffering, with the added slap in the face of stringent World Bank conditions. Compare this with the hundreds of billions chucked at bailing out the banks, with minimal conditions, and the injustice gets gut-wrenching. Read more about Climate Justice in New Internationalist, No 419, 2009.