Medical Therapy and Health Maintenance for Transgender Men: A

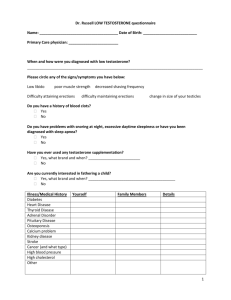

advertisement