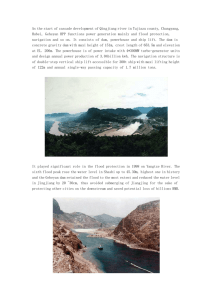

Cahora Bassa Dam, Mozambique 1965–2002

advertisement