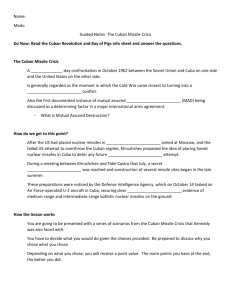

Timeline – Cuban Missile Crisis

advertisement

Cuban Missile Crisis 1 Mariam Shadid Timeline – Cuban Missile Crisis Date Event January 1st 1959 Batista flees Cuba February 16th 1959 Fidel Castro (Marxist Leninist) assumes power and becomes Premier of October 28th 1959 NATO signatories, Turkey and US jointly agree to deploy 15 Jupiter February 1960 Russians sign a trade agreement with Cuba to exchange Cuban sugar May 7th 1960 Cuba and USSR establish diplomatic relations July 8th 1960 Eisenhower administration responds by cutting back Cuba’s sugar Cuba missiles to Turkey as a defence against Soviet invasion or Soviet oil, machinery and technicians exports by 80%. This was followed by a US trade embargo on Cuba’s imports December 19th 1960 Cuba openly aligns its foreign and domestic policies with that of Russia August 1960 US begin to mobilise opposition towards Cuba January 3rd 1961 Cuban and US diplomatic relations are severed Early 1961 CIA begin training a group of 1400 Cuban rebels to overthrow Castro April 12th 1961 US president Kennedy states that the US will not intervene militarily in April 17th 1961 Cuban rebels invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. It was a failure. overthrowing Castro Cuban Missile Crisis 2 Mariam Shadid October 21st 1961 Kennedy publicises the absence of a conceived “missile gap”. Where the US possessed several hundred ICBMs, the Soviets only had 25. This highlighted Russia’s nuclear ineptitude May 21st 1962 Khrushchev suggests that the USSR should deploy missiles to Cuba June 10th 1962 Russian leaders all vote in favour to deploy missiles to Cuba. Castro agrees with the deployment and claims that it would act as a deterrent from a possible US invasion July 1962 Khrushchev’s rapid deployment of missiles leads to the installation of 36 MRBMs (Medium Range Ballistic Missiles) and 24 IRMs (Immediate Range Missiles) August 16th 1962 CIA director, John McCone suggests to Kennedy that the Soviets are October 14th 1962 A U2 spy plane reconnaissance mission took photographs of missile installing MRBMs in Cuba. sites in Western Cuba. By this stage, 42 000 Soviet troops are stationed in Cuba and 80 cruise missiles are in place October 15th 1962 National Photographic Intelligence Centre confirms the existence of October 16th 1962 McGeorge Bundy informs Kennedy of the presence of MRBMs in Cuba. (Day 1) the National Security Council. Robert McNamara, Secretary of Defence surface-to-air missiles Kennedy immediately establishes EX-COMM: Executive Committee of outlines the diplomatic and military courses of action to take. October 17th 1962 The majority of EX-COMM strongly advocate for a military air strike on (Day 2) (Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles) capable of hitting all of Cuba, rather than a blockade. Further U2 flights that night reveal IRBM continental US except for Washington and Oregon Cuban Missile Crisis 3 Mariam Shadid October 18th 1962 Kennedy and Soviet Foreign Minister, Andrie Gromyko meet. Kennedy advises Gromyko that missiles in Cuba will not be tolerated by the US (Day 3) October 19th 1962 Kennedy is torn between imposing a naval blockade on Cuba or to have a military air strike (Day 4) October 20th 1962 Kennedy is leaning towards a blockade. It would enable American (Day 5) equipment from reaching the island until the missiles were removed. A naval vessels to encircle Cuba and prevent any ship carrying military blockade would also enable the US to start with minimal action and increase pressure if needed, and possibly avoid armed conflict. October 21st 1962 Kennedy decides on a naval blockade, however is advised to use the (Day 6) international law is considered as an act of war, and by using the word word “quarantine” instead of “blockade”. A blockade, under “quarantine”, it made the Soviets appear to be the aggressors October 22nd 1962 Kennedy addresses the missile deployment in a 17 minute speech (Day 7) states that in order to “halt this offensive buildup, a strict quarantine which is televised nationally. He reveals the presence of missiles and on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated”. He received an overwhelmingly positive reaction towards his speech. Khrushchev replied to Kennedy in a letter that day, claiming that the missiles are for defensive purposes October 23rd 1962 The Organization of American States (OAS) approves the quarantine on Cuba (Day 8) October 24th 1962 Secretary General of the United Nations, U Thant, proposes a “cooling (Day 9) UN meeting, Soviet ambassador, Valerian Zorian denied the presence off period” and the Kennedy administration reject this proposal. In a of missiles in Cuba, whilst US ambassador Adlai Stevenson presented Cuban Missile Crisis 4 Mariam Shadid photographs of missile sites, humiliating the Soviets and winning over the UN. Kennedy decides to enact the quarantine the following day. Meanwhile, Soviet ships continue to approach the quarantine line, 805km away from the Cuban coast and the US military alert is raised to DEFCON 2; the highest level ever in US history. Kennedy ordered the navy to give "the highest priority to tracking the submarines and to put into effect the greatest possible safety measures to protect our own aircraft carriers and other vessels." October 25th 1962 EX-COMM discusses a proposal to remove missiles in Turkey, in exchange for the withdrawal of Cuban missiles (Day 10) October 26th 1962 EX-COMM receive a letter from Khrushchev, stating that the Soviets (Day 11) again. On Khrushchev’s part, this letter was seen as a willingness to will withdraw their missiles if the US pledge never to invade Cuba resolving the dispute. However, a CIA report reveals that missile sites are continually being developed and that the Soviets attempted to camouflage them October 27th 1962 A U2 spy plane flies off track and drifts into Soviet air space on what (Day 12) manage to shoot it down. Meanwhile, Khrushchev sends Kennedy was reported to be a “routine air sampling mission”. The Soviets another letter, demanding that the US withdraw their missiles in Turkey. The White House was “in hysteria”. Domestic pressures led Kennedy to respond only to Khrushchev’s first letter, and that way, he avoided publicly withdrawing Jupiter missiles in Turkey October 28th 1962 Khrushchev announces over the radio that the missiles will finally be (Day 13) Khrushchev’s office to write a letter, signifying the retreat of the removed from Cuba. That night, the Presidium gathered in Kremlin and the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis October Kennedy orders that the quarantine remains and also orders the Cuban Missile Crisis 5 Mariam Shadid 29th 1962 continuation of low level reconnaissance flights November 21st 1962 Kennedy lifts the quarantine on Cuba, after being reassured by the Late November 1962 US withdrawal of Jupiter nuclear missiles in Turkey Soviets that all missiles will be dismantled Explain The deployment of missiles to Cuba was influenced by several factors. Khrushchev’s need to redress the strategic imbalance of power which was initially tipped in favour of the US and his emotional investment in the Cuban revolution motivated him to deploy missiles to Cuba. This, coupled with the US’ reaction to the deployment of missiles culminated into the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Khrushchev’s need to redress the strategic imbalance which was in the United States’ favour was a contributing factor to his deployment of missiles in Cuba. As Gaddis explains, the Cuban Missile Crisis arose because Khrushchev understood more clearly than Kennedy that the West was winning the Cold War1. The installation of US Jupiter missiles in a bordering country of the Soviet Union2 was a politically3 and militarily threatening prospect for Khrushchev. With the missiles in close proximity, the Soviet Union was vulnerable to US nuclear attack which effectively disrupted the balance of power and as a result, the strategic balance tipped in favour of the US. This posed serious problems for Khrushchev who relied heavily on the notion of “Potemkinism”4 to conceal the presence of a missile gap. While Khrushchev led the US to believe that the Soviet Union were turning “missiles like sausages”, in reality, the Soviet Union only possessed 25 ICBMs, as opposed to several hundreds that the US had produced. However, Khrushchev’s primary objective in redressing the strategic imbalance was to enhance the Soviets’ ability to launch nuclear attacks on the US. By 1 Gaddis, John Lewis. Rethinking Cold War History, Oxford University Press (1998) pg. 247 In October 1959, the US deployed missiles to Turkey – a bordering country of the Soviet Union, as well as a NATO signatory 3 Thompson, Robert Smith. The Missiles of October, Simon and Schuster (1992) pg. 168 4 A phrase Gaddis uses to describe something that seems impressive but in fact lacks substance 2 Cuban Missile Crisis 6 Mariam Shadid deploying medium and intermediate range missiles for “defensive purposes” to Cuba only 90 miles off the coast of Florida, Khrushchev had effectively changed the military situation. This is supported by Gaddis who states “IRBM + Cuba = ICBM”. Post revisionist historians James Daniel and John Hubbell further this idea by arguing that “by moving intermediate-range missiles to Cuba… Russia was rapidly narrowing the gap... The presence of Russian missiles in Cuba had drastically altered the balance of world power.” Thus, by placing missiles in America’s “backyard”, Khrushchev had changed the military situation and as a result, corrected the strategic imbalance of power. The USSR’s deployment of missiles was also influenced by Cuba’s need for protection from an imminent US invasion as well as Khrushchev’s emotional attachment to the Cuban Revolution. The attempted invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 saw the emergence of the subsequent plan “Operation Mongoose”5. Castro looked to the Soviet Union for protection from an imminent US invasion and Khrushchev responded by deploying missiles. Khrushchev’s emotional investment in Cuba is illustrated through his decision to deploy IRBMs to Cuba in response to Castro’s appeals and American aggression. It is important to note that Cuba represented a thriving communist revolution that had occurred in a developing country and Khrushchev needed to ensure that it was successful in order to maintain his credibility, as he was at the forefront of communism. Moreover, the suppression of the Cuban Revolution would have meant the defeat for the whole socialist camp6, which directly influenced Khrushchev’s decision to protect Cuba from US imperialist aggression7, and consequently deploy missiles. Post revisionist historian Gaddis supports this notion, by claiming that the deployment of missiles to Cuba was “…both an old Bolshevik’s romantic response to Castro and to the Cuban revolution and an old soldier’s stratagem to defend an endangered outpost and ally.”8 Hence, the deployment of missiles was partially in response to American provocations and Cuba’s need for protection, as well as Khrushchev’s emotional attachment to the Cuban revolution. It can be argued that what essentially transformed the Cuban Missile Crisis into one of the most perilous of the Cold War crises was the response of the US to the deployment of 5 Also known as the Cuban Project, “Operation Mongoose” was a secret plan directed by the CIA which aimed at stimulating a rebellion in Cuba and removing the communists from power 6 Gaddis (1998) pg. 263 7 Thompson (1992) pg. 168 8 Gaddis (1998) pg. 263 Cuban Missile Crisis 7 Mariam Shadid missiles to Cuba. While Khrushchev’s first intention was to protect Cuba from American invasion, the US perceived the Soviet sphere of influence to be rapidly expanding into a neighbouring American nation. The discovery of missiles in the U.S’ figurative backyard was an alarming prospect for the White House and with the volatile congressional elections only three weeks away9 Kennedy needed to ensure he acted decisively as “such news would undermine the Democrat’s legitimacy in preserving the country’s security.”10 However, in response to the deployment of missiles to Cuba, EX-COMM advocated heavily for military retaliation, which effectively transformed the situation into a crisis. Thus, the Cuban Missile Crisis arose as a result of Khrushchev’s gamble as he deployed missiles to the U.S’ figurative “backyard”. Khrushchev was motivated by a need to redress the strategic imbalance which was in the United State’s favour and Castro’s acceptance of the missiles influenced the US to respond militarily. All these factors culminated into the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962; when the world teetered on the edge of nuclear precipice11. AsSess The Cuban Missile Crisis had an immense and significant impact on US-Soviet relations and essentially laid the foundations for the beginning of détente. The two superpowers acknowledged the importance of effective communication and flexible response during the crisis and this saw the establishment of a direct hotline between Moscow and Washington, which exemplified their willingness to manage and resolve future conflict. Moreover, the recognition of MAD prevented a full-scale conflict from occurring between the superpowers, thus reducing tensions. Paradoxically, MAD provoked an escalation of the arms race which resulted in the propagation of a number of bilateral treaties to manage nuclear disarmament and hence, saw an easing of tensions between the superpowers. The Cuban Missile Crisis led to improved diplomatic relations between the US and the Soviet Union. The two superpowers recognised the importance of effective communication and 9 LaFeber (2002) pg. 234 Professor Anouar Boukhars speaking at Old Dominion University, April 2001 http://www.ciaonet.org/access/boa03/index.html 11 Dobbs (2008) pg. 345 10 Cuban Missile Crisis 8 Mariam Shadid flexible response12 which was indicative of their willingness to manage and resolve future conflict. Historian Walter LaFeber stated that immediately after the crisis, Khrushchev began to try to prevent another such confrontation13 from occurring. However, in order to achieve this, an effective means of communication was needed to eliminate misunderstanding between the political protagonists, and this resulted in the establishment of a direct hotline between Moscow and Washington in 1963. The hotline was symbolic of improved US-Soviet relations and resulted in greater cooperation between Moscow and Washington. The aftermath of the Missile Crisis further saw the mutual recognition of each superpower’s sphere of influence, which impacted significantly on their later associations with one another, as evident in the lack of U.S intervention during the Czechoslovakia crisis of 1968. This notion is supported by historian Michael Dobbs who stated that “the United States and the Soviet Union would never again become involved in a direct military confrontation of the scale and intensity of the Cuban Missile Crisis.”14 Moreover, the significance of flexible response and compromise was also an important milestone in alleviating tensions between the US and the Soviet Union. Khrushchev’s letters to Kennedy, negotiating the dismantling of Jupiter missiles in Turkey, signalled a willingness to resolve the conflict. Similarly, Kennedy negotiated the conditions under which missiles would be removed from Turkey15 without “plunging the world into a catastrophic war”16 revealing the significance of compromise during the crisis. Hence, through the recognition of the importance of effective communication and negotiation, relations between the two superpowers improved significantly. Whilst the Cuban Missile Crisis led to an easing of tensions between the US and the USSR, it also contributed to the recognition of MAD which provoked an escalation of the arms race. After the Missile Crisis, Khrushchev and Kennedy’s policy of brinksmanship shifted to the recognition of Mutually Assured Destruction17 which promoted the escalation of the arms race to ensure that both sides had MAD in the event of a nuclear attack. The doctrine of MAD was seen to prevent a direct nuclear conflict between the US and the Soviet Union and 12 Dobbs, Michael. One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War, Hutchinson (2008) pg. 347 13 LaFeber, Walter. America, Russia and the Cold War, 1945-2002, McGraw Hill (2002) pg. 238 14 Dobbs (2008) pg. 349 15 Kennedy negotiated that the removal of missiles from Turkey would have no public concessions, as Khrushchev had initially hoped 16 Dobbs (2008) pg. 348 17 MAD - neither side will dare to launch an attack because the other side will retaliate, resulting in the destruction of both parties. MAD was seen to prevent any direct full-scale conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War Cuban Missile Crisis 9 Mariam Shadid hence, improved US-Soviet relations. Furthermore, in the aftermath of the crisis, the Soviets were motivated by a need to seal the “missile gap” and vowed to end their nuclear inferiority by building more weapons, thus escalating the arms race18 and as a result, Soviet spending on the proliferation of nuclear arms increased exponentially. Historian Walter LaFeber estimated that up to 25% of the economy was directed towards military expenditure19 after the missile crisis, exemplifying the Soviet need to redress their nuclear inferiority. Historian Dobbs supported this notion and stated that paradoxically to the easing of tensions, an escalation of the arms race arose so as to “erase the memory of Cuban humiliation”20. Thus, the recognition of MAD saw improved US-Soviet relations as it prevented a full-scale conflict between the two superpowers from occurring. The escalation of the arms race further saw the propagation of a number of bilateral treaties between the two superpowers to manage nuclear disarmament which saw an easing of tensions between the US and the Soviet Union. Historian Gaddis stated that although the arms race intensified, it was conducted within the boundaries of precise and specific rules21. With the escalation of the arms race came the need by both sides to regulate the amount of radioactive fallout as a result of nuclear weapons testing. This subsequently resulted in the ratification of several bilateral treaties between the superpowers which included the Anti Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972 and the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963. These bilateral agreements arose as both Kennedy and Khrushchev acknowledged the need for a “safer world”. Thus, the emergence of bilateral treaties between the two superpowers was symbolic of the political protagonists’ desire to reduce tensions through negotiations to limit nuclear arms22 and hence, saw improved US-Soviet relations. Therefore, the Cuban Missile Crisis had an immense impact on US-Soviet relations and saw an easing of tensions. The aftermath of the crisis underscored the importance of effective communication as well as flexible response between the superpowers. Although the recognition of MAD provoked an escalation in the arms race, it prevented a direct conflict from occurring and resulted in the proliferation of treaties to manage nuclear arms. 18 Thomas G. Paterson "Cuban Missile Crisis" The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford University Press 2001. University of Western Sydney. 15 June 2010 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t119.e0377> 19 LaFeber (2002) pg. 332 20 Dobbs (2008) pg. 349 21 Gaddis, John Lewis. Rethinking Cold War History, Oxford University Press (1998) pg. 280 22 George Bunn "The Limited Test Ban Treaty" The Oxford Companion to American Military History. John Whiteclay Chambers II, ed., Oxford University Press 1999. University of Western Sydney. 17 June 2010 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t126.e0501> Cuban Missile Crisis 10 Mariam Shadid Quotes “The United States and the Soviet Union would never again become involved in a direct military confrontation of the scale and intensity of the Cuban Missile Crisis.” – Michael Dobbs “[Escalation of the arms race was to] erase the memory of Cuban humiliation” – Michael Dobbs “The Cuban missile crisis arose because Khrushchev understood more clearly than Kennedy that the West was winning the Cold War.” – John Lewis Gaddis “IRBM + Cuba = ICBM” – John Lewis Gaddis “By moving intermediate-range missiles to Cuba… Russia was rapidly narrowing the gap... The presence of Russian missiles in Cuba had drastically altered the balance of world power” - James Daniel and John Hubbell “The suppression of the Cuban Revolution would have meant the defeat for the whole socialist camp” – John Lewis Gaddis “The world teetered on the edge of nuclear precipice” – Michael Dobbs “He [Khrushchev] was so emotionally connected to the Castro revolution that he risked his own revolution, his country and possibly the world on its behalf” – John Lewis Gaddis