held - Center for Global Environmental Education

advertisement

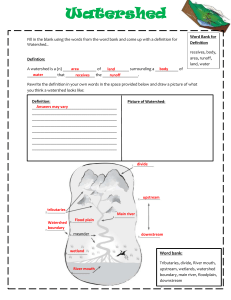

Rivers of Life Energy Odyssey Project Outline Objective 1: Complete Preparation Activities. Objective 2: Develop an Awareness of the Term Energy and its Sources. Activity 1: What is Energy? For younger students For older students Objective 3: Explore Energy Use Within your Watershed Activity 2: Energy, Past and Present Activity 3: Mining for Chocolate Chips Activity 4: The Petroleum Puzzle Objective 4: Explore Some Exciting New Renewable Energy Technologies. Activity 5: Parabolic Solar Cooker Activity 6: Tweety-bird Turbine Activity 7: Energy for Life Objective 5: Conduct an Energy Audit to See How You Use Energy. Activity 8: Conduct an Energy Audit Activity 9: A Contract to Save Energy Activity 10: Energy Story Objective 6: Map the Energy Resources in Your Watershed. Activity 11: Map your Watershed’s Energy Objective 7: Create an Energy Action Plan. Activity 12: Energy Action Plan 1 Rivers of Life Project Description Energy Odyssey explores the many ways that energy flows through your watershed. Activities focus on learning about non-renewable and renewable sources of energy, and how energy is connected to the process of creating a sustainable society. Students identify the resources from which energy is generated in your watershed. Energy audits of your school and of student homes indicate how energy use impacts local environments. Students also investigate untapped sustainable energy resources that will teach them how to better care for our rivers and the lands that surround them. OBJECTIVE 1: COMPLETE PREPARATION ACTIVITIES Preparation Activities: Getting Ready for Rivers of Life The activities below are recommended to help your class prepare for their online river adventure. The first activity, Introducing You and Your Watershed, introduces your class at the start of the program. Next is an activity that introduces watershed mapping—an activity that is common to all projects. Preparation Activity 1: Introducing You and Your Watershed Introduce your class and community to your fellow Rivers of Life participants by submitting this information in the Introduction Discussion Item in the Conference Center at the start of the program. That way, we will know who is with us. Please include the following information: • • • • • • Identify your class, grade level, school, and community. Identify your latitude and longitude (you may want to post a world map with pins marking locations of other Rivers of Life schools). Identify your school’s watershed, the river that flows through it, and the ocean it eventually empties into (see following exercise if your students need help answering this question). Tell which of the four Rivers of Life projects you’ll be undertaking. Share any other brief comment or greeting (a couple of paragraphs at most, please), including any work or study your school has done regarding rivers. Send, via e-mail or US mail, a photo of your class or school for posting in the Rivers of Life Conference Center. 2 Rivers of Life Preparation Activity 2: Mapping Your Watershed All four projects involve mapping activities that have common elements as well as elements specific to each project. This introductory mapping activity introduces the concept of a watershed and basic features of a river system, including river source, tributaries, confluences, river mouth, and direction of flow. For this activity, in addition to using a highway map and the topographic maps as described below, U.S. schools can also consult the watershed maps found at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Surf Your Watershed web site: http://www.epa.gov/surf/. These maps will help students recognize the borders of their watershed and its position in relationship to nearby towns. More detailed larger-format maps of each watershed can be requested from the EPA web site, though these maps may not be available for all watersheds. The larger-format EPA watershed maps can be received via the Internet or US mail. Background How do rivers change as they flow across the land? How do human activities affect the wellbeing of streams and rivers? You don’t need gills and fins to appreciate how important rivers are for maintaining and enhancing life. We draw an estimated ninety percent of our drinking water from the world’s rivers—yet that only represents ten percent of the water they provide us. Irrigation uses 65 percent and industry another 25. The world’s rivers were original highways and are still important for commerce, transportation, and recreation. Their banks have become sites for some of our greatest cities. Since ancient times, rivers’ mysterious ways and ever-shifting personalities have inspired musicians, poets, artists, and writers. Materials highway map USGS or other topographical maps and photocopies of those maps colored pens Procedure Wherever you stand on planet Earth, you’re always within a watershed—an area of land that drains into a river or stream. Explore the concept of a watershed by studying the course followed by a nearby stream. Step 1. Using a highway map, choose a small nearby stream to explore. Since a large stream may cover many of the topographic maps used in this activity, choose a stream less than about 16 km. (10 mi.) long. Step 2. U.S. schools can order copies of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographic “topo” map (or maps) that show the length your stream. Schools in other countries can check with government offices to see if similar topographic maps are available. A state index of USGS topo 3 Rivers of Life maps and the maps themselves ($4 each) can be ordered by calling toll-free 1-800-USA-MAPS. Also, local outdoor stores may have topo maps of streams in your area. (Note: To introduce the basic features of a watershed, this activity can be completed using any single topographical map [or contiguous series of maps] that has an entire watershed within its borders—it doesn’t have to be a map of a nearby stream. To save time finding and ordering local topo maps, you may find it easier to purchase from a local outdoor store topo maps of a regional or national wilderness area, which are more likely to be stocked than local maps of developed areas. ) Step 3. Photocopy the parts of the maps that show your stream and carefully tape the photocopies together to form one large map. Step 4. Mark with colored markers the source and mouth of the stream, confluences (meeting points) with any tributaries, wetlands, connected ponds or lakes, and any dams or rapids. Step 5. Figure out which way the stream is flowing on the map by studying the elevation numbers on those contour lines that cross the stream (descending elevation numbers indicates downstream flow). Draw directional arrows on the stream to show which way the water flows. Step 6. Trace the watershed boundaries of a small creek that drains into your stream. Follow the creek to its source, then continue uphill until contour lines indicate the land begins sloping downward. This ridge is the “height of land” separating the creek’s watershed from neighboring ones. Trace this meandering ridge line in both directions until you’ve drawn the boundaries of the creek’s watershed. Reflection Questions How many other small watersheds can you find on your map? What do colors and symbols on the topo maps suggest about how land is used in your stream's watershed? Can you estimate the height of any dams by studying the map’s contour lines? Do symbols and colors suggest what any dams may be used for? Project Introduction Stand beside a river wave, and watch the river flowing through it. Unendingly, the water rushes by—and yet the wave remains. Energy courses through our lives with equal mystery. It transforms itself to give us light, heat, sound, and power, while remaining a silent force largely unnoticed by us. Just as we need clean, safe water to drink for our very survival, we depend on energy in numerous ways throughout our lives. Indeed, flowing water and energy are so close in nature, they are sometimes one and the same thing. Historically, the wheels of industry throughout North America and elsewhere have been literally energized by the force of moving water. Hydropower is still a major source of 4 Rivers of Life electricity around the globe—in fact, the world’s greatest hydroelectric project is currently under construction on the Yangtse River in China. The impacts of our energy use connect with water in yet another way. Airborne pollution from the burning of fossil fuels gets deposited in lakes and streams as acid rain. Heated water discharged from nuclear power plants can alter aquatic ecosystems. Hydroelectric dams can significantly change in many ways the structure of the rivers whose power they tap. Technologies that reduce these environmental impacts and promise renewable energy sources deserve our attention. Energy Odyssey explores the many ways that energy flows through your watershed. By learning about our sources of energy, how we consume energy, and how these affect our watershed, we may discover more affordable, sustainable energy uses and resources that will help us take better care of our rivers and the lands that surround them. OBJECTIVE 2: ENERGY AND ITS SOURCES Activity 1: What is Energy? Background This activity will help students develop a conceptual definition of energy to use in this project. Their interest will guide their research into forms of energy that they can share with others in the classroom and on the ROL web site. Some background information may be helpful. Matter is easy to describe. It’s “stuff” that comes in familiar forms: solid, liquid and gas. It has mass. It has weight. You can usually see and feel matter—it’s tangible. Energy is more “intangible,” yet it underlies our abilities to perceive everything: the light we see, the sounds we hear, and the heat we sense by touch are all forms of this intangible thing called “energy.” Energy is difficult to define, but let’s start by saying: energy is any means by which matter can be changed. ENERGY INTRODUCTION FOR YOUNGER STUDENTS Procedure Step 1. Read the following story to your class and ask them to think about energy as you read. What is energy? You lean out your window and feel a breeze on your face. You climb a hill to see (your city/town) spread out beneath you. Its moving points of light seem to throb with energy. The movement of cars, people on the sidewalks, the flowing of the river—all is a swirl of energy. 5 Rivers of Life But the movement and lights of the city (town) are not the only forms of energy that surround you. You feel the energy of the wind on your face. As you walk down the street with earphones pouring great sound energy into your ears, you notice the sidewalk is cracked and slightly lopsided. Tree roots have grown under that sidewalk and the enormous energy of the tree’s growth has broken the concrete. A friend in Los Angeles, California, also has a cracked sidewalk, but there it was the relentless energy of movement of the ground itself that broke the concrete. It’s getting dark and cool outside. When you arrive home, you feel the warmth inside your house. The lights are inviting. You feel the energy from dinner begin to surge through your veins. Energy moves through you and around you. But, what is energy? Step 2. Allow students to brainstorm the question “What is energy?” by asking them to give examples of energy from the story. List responses on the chalkboard or poster paper. Ask students to think of examples of energy that weren’t mentioned in the story to extend the list. Save the list. Reflection Questions: What do you use energy for? Draw a picture of an energy source. Can you draw a picture of something at home that uses energy? How is energy used at home/school/in town? ENERGY INTRODUCTION FOR OLDER STUDENTS Materials 3 marbles of different sizes bottom half of a milk carton piece of corrugated cardboard about 8.5 X 11 inches pile of books, 6 inches high metric ruler student journals two plastic bottles white and black paint two small balloons small appliances: radio, tape recorder, lamp, etc. bright light magnifying glass things that make sounds: whistle, guitar, radio, etc. Procedure Step 1. Prepare the following small group activities in advance. Divide students into six groups. Tell them that they are going to “discover” forms or kinds of energy as they move from station to 6 Rivers of Life station. Have them write their observations in journals at each station. (Note: Do not label each station with the name for the energy form. Let students try to discover the energy form, even if they give it the “wrong” name. Also, you may want several parent volunteers to join you during the stations exploration.) Station 1: Potential and kinetic energy: Set up an area with three marbles of different size, an inclined plane about one foot high at its tallest point (the piece of cardboard supported by the books), a metric ruler, and a milk carton. Place the lower section of a milk carton at the bottom of the inclined plane to catch the marbles as they are rolled down the plane and measure the distance they move the carton. (Note: You should set this up ahead and try it out to be sure the inclination of the plane is such that the milk carton moves when the marbles roll into it.) The parent/teacher at this station can begin by placing the three marbles on a flat plane at the top of the inclined plane and asking the group these questions: What does it mean when your parents go to “work”? What do you think is the meaning of work? Which marble can work the hardest? If you put the marbles at the top of the plane, would they have energy? Why? Let the students experiment with rolling the marbles down the plane into the carton. They will observe that the milk carton moves a different distance for each marble. They can use their rulers to measure the distance the milk carton was moved. Which marble had the most energy? Why? How much more energy? How do you know? Record observations in journals. Station 2: Thermal energy—heat. Prepare in advance two plastic bottles, one painted white and one painted black. Place the open end of one small balloon over the mouth of the white bottle and do the same for the black bottle. Make sure the balloon forms an airtight seal. Take students outside and place both bottles in bright sunlight or to an area in the classroom with a sunlamp. Students will observe that the balloon on the black bottle will start to expand. The balloon of the white bottle will remain limp. Students can touch both balloons to notice that the balloon on the white bottle will be warm while the balloon on the black bottle will be much cooler. The parent/teacher can ask the following questions: What happened? Why do you think the balloon on the black bottle expanded? What does heat do to air? Why does a dark object get warmer in the sun than a light object? What would be a good color to paint your car if you wanted to stay cool in the summer? Record observations in journals. 7 Rivers of Life Station 3: Electrical energy. Explore the Franklin Institute’s web page on lightening: http://sln.fi.edu/franklin/tips/lightning.html. Then gather electrical appliances with power cords around the computer (for example, a radio, tape recorder, lamp, etc.) Students can examine the appliances after viewing the lightening simulation. Parent/teacher asks students the following questions? What do all of these items have in common? What kind of energy do these items represent? What is the source of their energy? (Where does it come from?) What happens when you walk across a carpet on a dry winter day and touch a metal appliance or pipe? Why don’t battery-operated appliances need power cords? Record observations in journals. Station 4: Electrochemical energy (food). Have students check their heart rates while sitting quietly. Then have them run in place, do jumping jacks, run up a flight of stairs, etc. Have them check their heart rate again after engaging in physical activity. Discuss these questions. Was there a difference in your heart rate before and after exercise? What made your heart beat speed up? Is your body warmer after working out? What does energy have to do with these observations? Lead students to the realization that the food they eat is turned into energy inside their bodies. Students may be interested in an integrated activity on the Explorer Home web site (http://explorer.scrtec.org/explore…er-db/html/835246811-81ED7D4C.html) that introduces the concepts of the food chain and the storing of energy as it pertains to both humans and animals. Another one is http://www.tamu-commerce.edu/coe/shed/espinoza/s/ellis-b-lp2.html Record observations in journals. Station 5: Light energy. Find a small room for students to enter. Ask them to observe what they see. Then turn off the lights and ask them to observe what they see. A second activity is to focus light from a bright lamp using a magnifying glass. Discuss these questions. What form of energy allows you to see? How does focusing a light source using a magnifying glass relate to energy? Why are fireworks so bright? Is this a form of energy? Station 6: Sound energy. Have available several items that make sounds (for example, a whistle, radio that is playing, guitar, etc.) After students have examined and manipulated the items, ask them to clap their hands, talk in a very soft voice, talk in a loud voice, sing, whistle. Discuss the following questions: 8 Rivers of Life What is music? Why can you “feel” the sound when you shout into your hand? How is the sound made by someone singing different than that same person talking? How can deaf people “listen” to music? Why are fireworks so loud? Is this a form of energy? How can you find out why the sounds are different? Students can then go to the Internet and conduct a search or explore one of the following activities located on the Internet: Making a Shoe-Box Guitar: http://www.eecs.umich.edu/mathscience/funexperiments/agesubject/lessons/guitar.html Whale Songs: http://aace.virginia.edu/go/Whales/LessonPlans/WhaleSongs.HTML Step 2. As an entire class, have students report on the different forms of energy they discovered at the stations. Help them with the energy terms. Go back to the list on the chalkboard or poster. Have students group the items on the list into the categories they’ve discovered. Extension Using the list of energy examples in Activity 1, ask students to think about where each energy example originated. For example, the heat in their homes may have come from the local utility (gas or electric), propane, or logs in a fireplace. List the energy sources next to the examples of energy. Some students may trace energy all the way back to the four major sources of Earth’s energy: nuclear fusion inside the sun, gravity, radioactive decay inside the Earth, and kinetic energy from the Earth’s rotation. OBJECTIVE 3: RIVERS AS A RESOURCE OF ENERGY Activity 2: Energy, Past and Present Background Students research energy use practices in their watershed to compare the past with present energy practices. Background information and references including URL’s are provided. Students are encouraged to research the role of aboriginal peoples, early settlers, and recent inhabitants of their watershed. Materials Refer to the watershed map students created at the beginning of Rivers of Life. Pencil and paper and/or computers for keyboarding their research Tape recorders with cassette tapes for students who choose to complete oral histories 9 Rivers of Life Procedure Step 1. Discuss with students the following questions to get them started: What sources of energy are suggested by your watershed map (e.g., hydroelectric dams, coal mines)? Do you have any information about energy use from the past you can share with the class? What would be the greatest challenges for people who settled in this area to meet their energy needs? When did electricity first appear? When did gas first appear? What did your great grandparents use for energy sources? List additional questions generated by the students. Step 2. Use research materials such as Internet search engines, reference materials located in your school’s Media Center and public library, the local Historical Society, and calls made to public utilities for any historical materials they may have to answer questions about early energy forms that may have been used in your watershed. Step 3. Have the students conduct interviews with great grandparents and other senior citizens who may have knowledge in this area. They can use tape recorders to record conversations (with permission from the interviewee) to create oral histories. Step 4. Students can demonstrate the knowledge they gain from their research by preparing an oral report to share with the class. This can be a narrative to describe their findings, which may include photos from historic sources and a summary of the interviews held with grandparents. (Note: If they prepare a tape-recorded oral history, they can play some interesting passages for the class to hear.) Activity 3: Mining for Chocolate Chips Background Many countries depend greatly on the use of oil and gas as sources of energy. You may have discovered that the heat in your home comes from natural gas and that a coal generator produced your electricity. Coal and petroleum (natural gas is a by-product of petroleum) are located underground. In order to use these resources, we must dig, or extract, them from the ground. Coal can be mined using several methods (strip mines that remove layers of earth, shafts that serve as tunnels to underground reservoirs); petroleum is usually mined by digging wells. The coal mining process is simulated in this activity that uses chocolate chip cookies. 10 Rivers of Life Materials Chocolate chip cookies - two per student Toothpicks, plastic spoons - one each per student Paper and pencil or journal to record observations Procedure Step 1. Discuss the mining process with your students. Tell them they are going to “mine” for chocolate chips today. Ask them what they can expect to learn about coal mining from this activity. Step 2. Pass out the chocolate chip cookies, toothpicks, and spoons. Tell students they are to work carefully to remove the chocolate chips from the cookies. You may want to describe the cookie as the land with imaginary trees, plants, and a number of animals that live amongst the flora. There may even be a river or stream running through their “land.” It could be flat, hilly, or mountainous. The chocolate chips represent coal. The challenge is to remove the chocolate chips as gently as possible in order not to disturb the land while keeping the chocolate chips whole. Students can work independently or in small groups. Step 3. Ask the students to record their observations. What does the cookie look like before “mining?” What difficulties did you encounter? How many chocolate chips were you able to “mine” that remained whole? What does the cookie look like when you finish? Step 4.. When students have recorded all information, take a break and eat the cookies! Reflection Questions What happened to the cookie when you removed the chocolate chips? What impact might real mining have on the land compared to cookie mining? How many people depend on coal mining directly and indirectly? Is coal a renewable resource? Why or why not? Ask additional questions that emerge during the discussion. The coal mining process is not identical to their experience with the chocolate chip cookies, but the importance of the activity is to help students discover the concept of mining. Extension For further investigation of this subject, explore the following URL’s: Coal and Coking on the Internet http://www.mlc.lib.mi.us/~stewarca/coalandcoke.html Coal Introduction http://www.eia.doe.gov/fuelcoal.html 11 Rivers of Life Activity 4: The Petroleum Puzzle Background The Energy INFOcard is an interesting web site (http://www.eia.doe.gov/neic/infocard96.html) that provides current energy consumption information. We can see that the United States, with four percent of the world population, uses about 25 percent of the world’s energy. Most of the energy we use comes from nonrenewable sources—petroleum, natural gas, and oil. The following two tables illustrate how we use energy: US Energy Consumption Oil ........................................ 38% Coal ...................................... 22% Gas ....................................... 24% Nuclear ................................... 8% Renewable .............................. 8% World Energy Consumption US ........................................ 25% China .................................... 10% Russia ..................................... 7% Japan ...................................... 6% Germany ................................. 4% Other .................................... 48% As you can see, we rely on large amounts of nonrenewable resources. We know our reserves of these resources are being depleted, so we are beginning to look into alternative energy sources. But running out of gasoline, coal, and natural gas is only one problem. Our use of some of these resources has caused problems. For example, using gasoline in our automobiles is one reason why our atmosphere may be heating up in a process called “global warming.” Materials Poster paper Markers Small Post-its Procedure Step 1. This activity will assist students with an exploration of the petroleum industry. As a prompt for this activity, ask students to listen while you read the following paragraph: 12 Rivers of Life Even people who “get away from it all” depend on petroleum. The campers’ tent, the mattresses they sleep on, their rain gear and footwear are all derived from petroleum. Using white gas (made from petroleum) to cook their meals avoids woodcutting, thus helping to preserve the wilderness. What do you think? Step 2. Facilitate a discussion about the paragraph you just read, asking students what was meant by “getting away from it all?” Discuss the products made from petroleum mentioned in the paragraph. The discussion can be open-ended, allowing for students to piggy-back off each others’ comments to see where it leads. Step 3. Put students in group of three with a package of Post-its. Ask them to discuss using white gas for cooking when camping rather than wood. They are to consider two questions: What are the benefits to the environment of using petroleum (in the form of white gas) rather than wood? What are the benefits to the campers of using petroleum rather than wood? Can you think of some benefits of usin g wood? They are to think of as many benefits as they can and to write each one on a separate Post-it note. Step 4.. Using the poster paper, draw two large overlapping circles. Label one “Benefits to the Environment,” the other “Benefits to the Campers.” Step 5. Ask students to bring their Post-its up to the poster paper and place them in the appropriate places. The overlapping area is for benefits to both. Step 6. Lead a discussion about the results. The objective is for the students to realize that there are many sides to any issue. The discussion may result in disagreement among the students. This can be used as an opportunity to emphasize the importance of developing a global, or allencompassing, perspective when discussing issues. Reflection Questions Was this easy? Did any of the things you discussed seem puzzling? What were they? We didn’t write down the negative things that could result from using petroleum or wood. Do you think there are any negative outcomes from using petroleum or wood? Extensions The Petroleum Communication Foundation can answer your questions about the petroleum industry. They supply current literature that is reviewed by experts. They will dig up information for you from their library or refer you to experts about everything from climate change to gasoline pricing. They supply school teaching aids, slides, videotapes. They will provide expert speakers on key subjects. Just ask! http://www.pcf.ab.ca/educad.html For links to Frequently Asked Questions, Facts About Oil in our Daily Lives, and Monthly Petroleum Facts at a Glance visit http://www.api.org/facts.htm. 13 Rivers of Life OBJECTIVE 4: RENEWABLE ENERGY TECHNOLOGIES Activity 5: Parabolic Solar Cooker Background (Note: Information about solar energy is provided by the Department of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Clearinghouse, October, 1995.) Have you ever sat in a car that was closed up on a sunny day? Did you notice how hot it was in the car? This warmth is just one example of solar heating. We can use the energy in sunshine to warm our homes, heat our water, and provide electricity to power our lights, stoves, refrigerators, and other appliances. This energy comes form processes called solar heating, solar water heating, photovoltaic energy (converting sunlight directly into electricity), and solar thermal electric power (when the sun’s energy is concentrated to heat water and produce steam, which is used to produce electricity). The following resources can be used to introduce students to alternative forms of energy: Explore Power to Spare, a CD-ROM on Minnesota’s Renewable Energy Resources produced by the Izaak Walton League of America. Version 1.0 for Macintosh or Windows. This CD will be provided to all schools participating in Rivers of Life (if they are still available). The program provides students with an introduction to wind, solar, and biomass fuel for energy. The Bio-energy Information Network provides information about fast-growing trees and grasses for fuels. You can order a free package of biomass education materials from this site: http://www.esd.ornl.gov/bfdp The eco-nnections web site is an environmental curriculum for the elementary school. This Web site provides you with introductory material to solar, wind, biomass, hydropower plus an address for ordering more in-depth curriculum: http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~pack/ The following web page is a catalog for the buying, trading, and selling of alternative energy devices (AEEX - Alternative Energy Equipment Exchange). http://www.peak.org/~kenneke/aeex.html Materials Parabolic Solar Collectors (4-5 students can use one simultaneously) made from an old umbrella lined with silver mylar. Flavored marshmallows. Note: get the kind that comes in different colors. The colors are important in the assessment of knowledge. Uncooked spaghetti noodles (as thick as possible). These are used as skewers. The kids eat them after they roast their marshmallows (no trash!). 14 Rivers of Life Procedure Step 1. Brainstorm various types of energy sources with the whole class. Include solar energy if it isn’t mentioned. Ask the class if they believe this area is suited for solar energy. If students in a particular area think their location is usually too cold to make use of solar energy, ask them about sunny versus cloudy days so they will begin to think in terms of the sun’s rays rather than heat. Tell them they will be experimenting with the sun as a source of energy. Step 2. A clear, sunny day is a necessity for this activity. It need not be a hot day but it must be sunny. Step 3. Around 11:00 AM, place the cookers in the sunlight in an area where no shadows will be cast on them. This will allow the cookers to heat up prior to use. Step 4. Review the angle of reflection concept with the students (the sun’s rays are more direct at 12:00 noon than any other time of day). Step 5. Explain that there is a way to determine the hot spots on the cookers. Ask for suggestions, and then model the process for them by placing your hand about six inches above the rim of the cooker. With closed eyes, slowly rotate your hand around the perimeter of the cooker. When you find the spot that is hottest, slowly raise your hand until the heat comes to a localized point. The hot spot is where you want to hold your marshmallow. (This can also be determined by using a piece of paper. Place the paper over the hottest area until the light comes to a point on the paper. It is preferable to have the children feel the heat however.) Step 6. Have the students choose the marshmallow they would like to roast and allow them to skewer them using the spaghetti noodles. Step 7. Carefully listen to the children’s observations related to the various cooking time of the different colors. Allow plenty of time to discover why some get finished before others. White will never roast. Chocolate gets finished fastest, and the others vary based on how light the color is.). Hold a discussion based on the results. Reflection Questions What do you think would have happened if the temperature today was much higher and it was warmer outside, but there were clouds in the sky? Can solar energy be used anywhere or only in some locations? Why? If you wanted to design a solar collector, what color would you want it to be? Why? Extension Students can design different types of collectors that will hold water. These can be placed outside in the sun on a clear day and tested at 15-minute intervals to determine which heat the fastest. Someone from your class can be selected or volunteer to describe the results of this activity and post it on the Energy Odyssey Web site for comparison with other schools and other locations. 15 Rivers of Life Activity 6: Tweety-bird Turbine The information for this activity was adapted from material provided by the Natural Resources Defense Council. Background One of the oldest forms of energy harnessed by human beings, wind power, offers alternatives to our society’s current dependence on fossil fuels. Using advanced technologies, modern wind turbines are able to produce electricity for homes, businesses, and even utilities. Wind turbines are moved by the wind and convert this kinetic energy directly into electricity by spinning a generator. They use air foils or blades like the wing of an airplane to turn a central hub, which is connected through a series of gears to an electrical generator. The generator technology is identical to that employed by traditional fossil fuel generating plants. Wind turbines range from small residential systems to large utility systems. Wind energy has received high praise overall from energy and environmental experts, and offers utilities pollution-free electricity that is nearly cost-competitive with today’s conventional sources. Major utilities that implement modern wind harnessing technologies into their energy production strategies stand to gain significant economic advantages while offsetting emissions of carbon dioxide and other pollutants. Wind power is another example of how some of humankind’s earliest forms of energy provide a key link to a non-polluting future. Materials Several pinwheels purchased from a toy store Student journals to record observations Art supplies that include markers, colored pencils, fabric, popsicle sticks, pipe cleaners, etc. Procedure Step 1. Take students outside on a windy day and let them experiment with the pinwheels. Ask them how they think wind can be a source of power. Have them write reflective responses to the pinwheel activity in their journals. Step 2. Use the background information provided above to lead a discussion about the use of wind to generate electricity. You may want to have some pictures of wind turbines to show the class. Step 3. Explain that while wind power may be one of the most environmentally friendly sources of power, wind energy developers and environmentalists alike are concerned that bird deaths from collisions with wind turbines could pose a major obstacle to widespread use of the technology. In light of the problem, biologists are trying to discover why these accidents occur so that engineers can design turbines which raptors and other birds will be better able to avoid. 16 Rivers of Life Step 4. Engage students in a discussion about the bird situation. The objective is to help them realize that there are costs to each and every energy option. Step 5. Put students in groups of two or three and ask them to first discuss a design for a “safe” wind turbine that would still harness wind power. Then ask them to create their turbine from the materials provided. Give them a specified amount of time. Tell them that they are expected to describe their turbine to the whole class, pointing out the features that make it safer for birds while at the same time capture wind to use in the generation of electricity. Extension Find out if there are any wind “experts” in your area that can come to the classroom for a presentation. Have the class prepare questions to ask ahead of time, and assign a reflective paper to be written following the visit that has students write one or two things that resonate with them (is meaningful) and one thing about wind power they will share with their families. Activity 7: Energy for Life Material for this activity was adapted from AgMag, The Magazine of Minnesota Agriculture in the Classroom, Volume 7, Issue 2, 1992/93 and Volume 10, Issue 3, 1995/96. Background When you burn a log in your fireplace or in a campfire, you are using biomass energy. Because plants and trees depend on sunlight to grow, biomass energy is a form of stored solar energy. You already know that agriculture provides much of the energy you use each day in the form of the food you eat. But did you know that your electricity and the fuel for your car may also be coming from the farm? Although wood is the largest source of biomass energy, we also use biomass energy crops to produce electricity and fuel for our cars. Energy crops are crops grown specifically for their fuel value, including food crops such as corn and sugarcane, and nonfood crops such as poplar trees, alfalfa, and switchgrass. The most commonly used biofuel in the United States is ethanol, which is produced from corn and other grains. Ethanol is a liquid fuel that can be blended with gasoline. It is made from many different things including grains, cheese whey, paper, garbage and grasses. In many places in the world, much of the ethanol comes from sugar cane. But in the United States, we make most of our ethanol from corn. Ethanol is a renewable resource that stretches the supply of gasoline, a nonrenewable resource. And there’s more good news. When we make more ethanol-blended gasoline, we don’t have to 17 Rivers of Life buy as much oil from other countries. We don’t have to depend on other governments as much, and we save money, too. Making ethanol from corn is a major U.S. industry, producing nearly 1 billion gallons each year. (“Science Projects in Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency,” American Solar Energy Society, 1991). The processes for converting biomass to fuels include a broad range of thermal, chemical, and biological processes. An oversimplification of the making of ethanol is that corn kernels are delivered to a fuel “factory” to be made into ethanol. Sugar cane, potatoes, beets and other crops can also be made into ethanol. Livestock feeds widely grown in the Midwestern U. S. include alfalfa. Alfalfa can be a good energy crop. The roots of these hardy plants remain in the soil and keep growing year after year (reducing the risk of soil erosion, thereby helping to keep our water clean). The plant tops are easy to harvest with the equipment farmers already have. The leaves become food for livestock and the stems become fuel for energy. Crops like alfalfa could generate electricity to meet future energy needs. Crops we now feed to livestock could become your writing paper. This new product is just around the corner. Corn stovers (that’s the stalks and leaves left in the cornfield after harvest) will be turned into pulp and pressed into paper. It’s “trash to treasure,” or waste into useful things. Scientists tell us rice straw may also become paper in the future in the United States, just as it has been in the Orient for years. “Woodn’t” this be good news for trees? Materials Three sheets of poster paper Markers Reference materials including computers with Internet access Procedure Step 1. Begin by asking a volunteer from your classroom to look up “technology” in a dictionary. Then ask: What do we mean when we say agriculture and technology are teaming up? (Agriculture is being paired with scientific technology and used in new ways to meet the needs of people.) Can you think of any examples of how technology and agriculture have teamed up? Step 2. Lead a classroom discussion about recent innovations in agriculture. Step 3. Share the background information about biomass with your class as an introduction to biomass as an energy source. Step 4. Label each of the sheets of poster paper with the following headings: Know, Want to Know, Learned 18 Rivers of Life Step 5. As a whole class, brainstorm what the class knows about biomass as an energy source. Write items on the “Know” poster paper. Step 6. Do the same for items students want to know and list on the “Want to Know” poster paper. Some questions that the teacher can suggest if students get stuck are the following: How much food energy do you use every day? Can energy be recovered from food processing waste? Can garbage be converted into methane? What gas is given off during fermentation? How well do alcohol-gasoline mixtures work in small engines? Does using biomass as an energy source improve the environment? What does technology have to do with any of this? Step 7. Decide as a class how to answer the questions. Give the students the option of working independently or with a partner on one of the questions or an idea of their own. Step 8. Give students a specified amount of time to complete their research and report their findings to the class. Schedule a day to share final reports. Step 9. After sharing the students’ research reports, fill out the “Learned” piece of poster paper with a list of student-generated facts and information they learned about biomass. Step 10. Ask students to write a two or three paragraph reflection paper that describes why teaming up agriculture with technology is important in their lives and in the future. Ask several volunteers to share their reflections with the class. Resources Some useful references for this activity are listed below: Curriculum Connections to Agriculture, A Project of Minnesota Agriculture in the Classroom, Reproducibles for Secondary Educators, 1997. c/o Minnesota Department of Agriculture, 90 West Plato Boulevard, St. Paul, MN 55107 Science Projects in Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency, A Guide for Elementary and Secondary School Teachers, 1991. National Energy Foundation, 5225 Wiley Post Way, Suite 170, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84116. Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, U. S. Department of Energy, 1-800-2732957 or e-mail: doe.erec@nclinc.com. Department of Energy: Learning About Renewable Energy http://www.eren.doe.gov/erec/factsheets/rnwenrgy.html For information on renewable energy in the U.S., contact your Extension Office. In Minnesota, contact the Center for Alternative Plant and Animal Products (CAPAP) at the University of Minnesota, (612) 625-4707. 19 Rivers of Life Extension Make a corny craft! Corn cobs and husks have been popular toys and craft materials since early American Indian times. Try your hand at making a corn husk person. Materials Several very dry corn husks Large bowl of warm water String 1. Briefly soak the husks in warm water for easier handling. 2. Choose several strong husks and fold them in half. Using a length of string, tie off a “head” from the folded end. 3. Insert two or three smaller husks beneath the “neck” string to make two arms. Tie a “waist” string below the arms. 4. Shape the husks below the waist into some legs (tie each at the ankle) or a skirt. 5. Clothe or decorate your person with fabric scraps, buttons, ribbon, markers, etc. It’s your choice! 6. Group the corn husk people together and take their picture. Send it to us, and we’ll post it on the Web site. OBJECTIVE 5: DISCOVER HOW YOU USE ENERGY. Activity 8: Conduct an Energy Audit Background (The following activity is adapted from Earth Day 1990 Lesson Plan Guide, co-sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation and Esprit.) Energy is a vital part of our everyday lives. Food provides us with the energy to live and grow. We depend on electrical energy for our refrigerators and lights. Natural gas provides us with energy for hot water in our homes. Our cars and buses require energy from gasoline. We depend on energy in various forms for everything we do. As a nation we have become economically dependent on large amounts of energy. This dependence has caused problems like air pollution and acid rain (caused by burning fossil fuels like petroleum, oil, natural gas) the possibility of damaging oil spills (caused by drilling rigs or tankers) political and military tensions (caused by dependence on foreign oil), the dwindling supply of oil and other fossil fuels, and safety questions about nuclear power plants and the wastes produced there. We saw in “The Petroleum Puzzle” that the United States has 4% of the world population but uses 20% of the world’s energy resources. Because of our energy use, the United States is one of the world’s largest polluters. 20 Rivers of Life Using more energy-efficient equipment (cars, appliances, factory machines, and the like), eliminating unnecessary energy uses, and conserving energy could greatly reduce the United States’ high per person energy use. This activity focuses students’ attention on the energy they use in their homes. Materials Copies of the Home Energy Survey -- one per student. A sample is included in this Activity Guide for your convenience. Butcher paper to prepare a bar graph that is large and wide enough to accommodate many kinds of appliances as well as a large number of each kind Markers Procedure Step 1. Display a few common household appliances that use energy. Ask students to determine advantages and disadvantages to each appliance. Step 2. Tell students that they will tally the kinds and number of energy-using appliances in their homes. Explain that students are to look for and record only those appliances that use energy, not appliances that are human-powered. Ask students to suggest some energy-using home appliances. If they do not name refrigerators and water heaters, mention them. These two appliances are big energy consumers in most homes. (Your heater, water heater and air conditioner are the largest users of energy in the home. Among appliances, refrigerators account for about 33%, washer and dryer account for around 21%, lighting - 17%, stoves - 12%, miscellaneous items such as hair dryers - 11%, and televisions approximately 6%.) Step 3. Hand out the Home Energy Survey and explain how you want students to record their information. Keeping a tally, as the example shows, is a convenient way for students to record their data. Have students estimate the total number of energy-using appliances they have at home and record this prediction on their Home Energy Surveys. Emphasize that you want students to survey each room in their house, if possible, in order to get the most accurate count. Step 4. Post the bar graph and allow time for students to add their results. (Students may need to add data during recess or the lunch period in order to record it all.) Make sure students understand that they are to record the kind and number of each appliance they found at home; for example, they should color in three squares in the TV column if they have three TV’s in their house. You can model how to complete the graph by entering your data first. Step 5. Discuss the information on the graph. Ask, “What is the most common appliance? Which appliances are least common? Which appliances do you think use the most energy? How can you tell? 21 Rivers of Life Step 6. Choose an appliance from the graph and write it on the board. Ask students to think of an alternative that would use less energy. As a class, list the benefits and consequences of the appliance and the alternative. Repeat the exercise with one or more appliances. Step 7. Ask someone in the class to copy the results of the bar graph to send to the Rivers of Life Web site to post on the Energy Odyssey site. We will post your results with those of other classes from around Minnesota, other states, and other countries so that your class can compare and contrast their results with others. Step 8. As a class or in small groups access the following Internet site: http://www.edf.org. It is interactive, producing a detailed set of environmental facts about your family’s use of electricity, including what kinds of power plants are used to generate your electricity and how much pollution is produced. Click on “energy,” then on “Find out about your electricity.” Use of this web site should produce a great deal of lively discussion! 22 Rivers of Life HOME ENERGY SURVEY HOME APPLIANCES ______________________________________________________________________________ Estimate of the number of appliances in my home:_______ Name:_____________________________ List all the appliances you have in your home. Record the number of each kind you find. Example: 23 Rivers of Life Reflection Questions How accurate were your estimates about the number of energy-using appliances in your home? Which of the appliances on the list do you really need? Are there appliances on the list that you think you do not need? Is there a difference between an energy “need” and an energy “convenience” Do we use more energy than we need? How do we waste energy? Is energy conservation important? Why or why not? How can we conserve energy? What changes could you make in your home right now to conserve energy? What do people usually consider when they make a choice about something that uses energy? Extension The United States Environmental Protection Agency has developed a program that is involved with the research and development of energy-saving products. Their URL is recommended for students who are interested in learning more about energy-saving devices: http://www.epa.gov/energystar.html There are Internet addresses that offer home and building audits for students who desire a more detailed description of their energy expenditures. Interested students could use one of the audits to learn more about energy use in their school. http://ecep.usl.edu/ecep/audits/audits.htm http://www.iclei.org/audit/index.htm (Online Home Energy Audit) http://www2.solarnet.org/1/mpotts/Audit.htm http://www.tu.com/heet 24 Rivers of Life Activity 9: A Contract to Save Energy Background After determining how much energy they use, students decide what actions they would be willing to take for one week to save energy, write a contract stating their intentions, then discuss the results after a week. Materials Butcher paper Markers Procedure Step 1. Write an energy contract on the butcher paper to serve as a model for the students. Step 2. Ask students to explain why we should care about conserving energy. This is a good time to cover current energy-related issues in the news. Step 3. Ask students to suggest ways they can save energy. Introduce a student to the notion of saving energy by making choices that save energy. Such choices might include taking short showers, not leaving water running while washing dishes, closing the refrigerator door as quickly as possible, and turning off lights, televisions, radios, and stereos when no one is in the room. Step 4. Ask students how these energy-saving measures would benefit their watershed. Step 5. Ask students to decide on one or more ways they will conserve energy for the next week. Post the sample energy contract stating a week-long commitment to conserve energy. Students can work in small groups to discuss and write their contracts or work independently. Collect and save the contracts until the week is over. Some of the contracts can be e-mailed to us for posting on the Energy Odyssey Web site. Step 6. Tell students that each night they are to write two or three sentences about how they are saving energy in their journals. During the week ask students periodically how they are doing and find out if they are running into any difficulty keeping their contracts. Step 7. At the end of the week, return the contracts to students. Ask students to re-read their original contract and then write a summary explaining whether they were able to follow their plan, what difficulties they found, any unusual thing that happened, anything they learned about their habits and use of energy, and how they felt about making choices to conserve energy. Ask volunteers to share with the whole class. Reflection Questions Were you able to follow through with your plan to conserve energy? Why or why not? Was it easy or hard? Why? What would make it easier for you to conserve energy? What do you think might make it easier for other people to conserve energy? 25 Rivers of Life Activity 10: Energy Story Background Students develop a story that creatively and accurately incorporates their understanding of fundamental and essential energy-related concepts. Materials Pencil, paper or computers for keyboarding Procedure Step 1. Brainstorm what students have learned about energy in their watersheds. As students suggest concepts, develop a list on the chalkboard of energy vocabulary (for example, fossil fuels, hydropower, wind and solar power, biomass energy, etc.). Step 2. As a class, decide what kind of writing the students will do -- a creative story that incorporates energy concepts or a factual “report” of what students have learned. Brainstorm ideas. Step 3. Give students ample time to prepare a first draft. Encourage them to write expressively and descriptively. This is a first draft that will be reviewed for both content and grammar. Step 4. Put students in groups of two to serve as peer reviewers. Provide them with the following list of Five Steps to Peer Conferencing on Writing: 1) Writer reads the piece aloud. 2) Peer gives one or more positive comments. 3) Writer indicates where help is wanted. 4) Peer asks one or more questions about the writing. 5) Peer makes one or more suggestions to the writer. Step 5. Students write a second and final draft after the peer conference. Volunteers may share their stories with the whole class. Select two or three to send to us for posting on the Web site. OBJECTIVE 6: MAPPING ENERGY RESOURCES IN YOUR WATERSHED Activity 11: Map your Watershed’s Energy Background This is a mapping activity that builds on the previously produced watershed map, adding energy resources in the watershed located by the students. Return to the maps of your watershed you constructed at the beginning of Rivers of Life. You will use these watershed maps to add the energy resources located within your own watershed. Students will be investigating the location of public utilities and other energy producers and also 26 Rivers of Life looking at their watershed to determine whether or not it contains used as well as unused alternative energy resources. Remember that by alternative, we mean energy that is supplied by something other than conventional methods of using fossil fuels (coal, petroleum, natural gas). Some examples are energy provided by the wind, the sun (solar power), energy from plants (biomass), and water (hydropower). Materials watershed maps colored pens local telephone directory telephone computer with access to the Internet Procedure Step 1. Look at your watershed map and discuss what the colors and symbols on the topo map suggest about how land is used in your stream’s watershed. Is there any farmland? What are the crops used for? Are there any dams? How are they used? If this is not evident by looking at your map, how would you find out? Are there any large cities in your watershed? Towns? What are the energy needs of the people living in your watershed? Is the energy used by the people living in your watershed provided by sources within the watershed? How can we find out? Step 2. Have students work in small groups. Ask them to check in the telephone book for utilities that may be supplying energy within the watershed. (Note: This is an opportunity to teach some research and language arts skills.) Ask for volunteers from the class to make telephone calls to the utilities to ask questions about their service area. You may also want to schedule a visit from a utility spokesperson to your classroom to discuss the kind of energy supplied by the utility. Most utilities are honored to accept such an invitation. Before asking the next question, you may want to refer back to some of the eb sites introduced at the beginning of this activity with regard to alternative energy forms. Are there resources within your watershed that may be used for alternative, or renewable, forms of energy? . Think about the kinds of energy discovered earlier (potential and kinetic, heat, electrical, food, light, sound). How do you heat your home? How do you light up your home? Do you watch television, listen to the radio? Do you use a hair dryer when you wash your hair? Do you use an electric blanket when it’s cold? . 27 Rivers of Life When students answer the questions about energy use, have them work in small groups to check in the telephone book to locate the utility or utilities that supply the energy. If the addresses are in your watershed, draw symbols on the map that represents the energy sources. If they are outside of your watershed, draw the symbol outside the watershed boundaries and use arrows to indicate the direction of the energy. (For example, from the utility to their house.) Reflection Questions Does most of your energy come from nearby or far away? Are there any resources within your watershed that are not being used as an energy resource? Do you think the resources within your watershed are being used in a way that benefits your watershed? Why or why not? Can you suggest any other methods to get the energy you need? Does your energy source use fuel or not? If fuel is used, is this fuel replaceable/renewable? Are there side effects from the use of this energy source? OBJECTIVE 7: CREATE AN ENERGY ACTION PLAN AND USE IT! Activity 12: Energy Action Plan This is a culminating activity for Energy Odyssey that serves as an assessment. Students will develop an action plan that promotes positive behavior regarding energy use, helps resolve an energy-based issue, or both. Students will choose the best action based on careful analysis, research and implement the plan, and evaluate the results. Examples of action plans could include developing and implementing an energy conservation plan for their home or school or preparing and conducting public education projects about conserving energy at work or school. You will be provided with prompts for completion and resources on the Energy Odyssey web site. Plans will be posted on the web site Extension You may want to engage your class in a debate over the benefits and problems encountered by the use of hydropower. As with the action plan above, we will provide you with prompts for the debate on the web site. You can conduct your debate within your classroom, or participate on our web site with other classrooms. 28