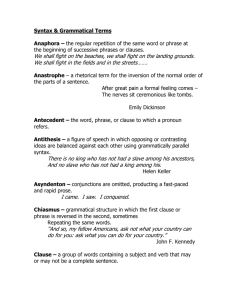

“Inversion” and focalization

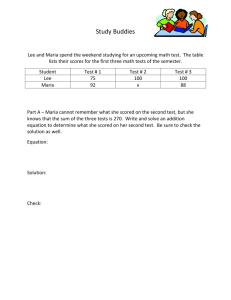

advertisement