Does forced solidarity hamper entrepreneurial activity

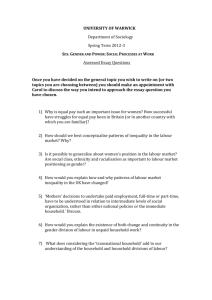

advertisement