Teaching Vocabulary Through Literature

advertisement

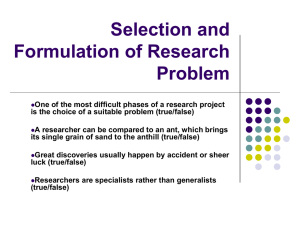

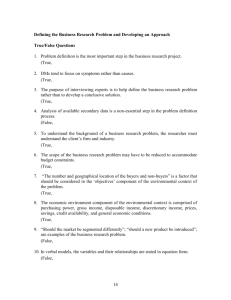

Teaching Vocabulary Running head: TEACHING VOCABULARY THROUGH LITERATURE Teaching Vocabulary Through Literature: Effects of Context-Clue Instruction on Tenth-Grade Students Dena H. Rogers Valdosta State University 1 Teaching Vocabulary 2 Abstract This study examined the effects of context-clue instruction on 24 advanced-level tenth-grade students to show if the method for learning words had an impact on student learning. Students were exposed to two methods of vocabulary instruction over nine weeks, word-list instruction and context-clue instruction. Results were determined using vocabulary tests, student observation checklists, and student surveys. Though neither the word-list nor context-clue instructional method produced significant changes in achievement scores, the other data-collection instruments showed that students had a preference for context-clue instruction when given the choice. When writing, students showed a higher usage rate for words learned through contextclue instruction than word-list instruction. Teaching Vocabulary 3 Teaching Vocabulary Through Literature: Effects of Context-Clue Instruction on Tenth-Grade Students High-school language arts teachers have many responsibilities. In addition to teaching literature and reading comprehension, grammar and mechanics, and the writing process, they must also teach vocabulary. Because of all their other instructional responsibilities, the teaching of vocabulary sometimes falls from the forefront of the curriculum and becomes a pointless routine rather than an essential instructional practice. Vocabulary instruction is not an easy task. Sometimes it is difficult to teach because students tend to be unwilling to learn new words as they grow up in a society where sophisticated language can be deemed undesirable. Manzo, Manzo, and Thomas (2006) reported that the influx of reality television, rap music, and other pop-cultural factors make those using intellectual language appear conceited. Similarly, the increase of students coming from lower socio-economic families and from diverse backgrounds is on the rise. Rupley and Nichols (2005) reported that by the year 2020, nearly 5.4 million students will be living in poverty. This state of deprivation means that educators need to make instruction as meaningful as possible because, no matter the obstacles they may face, students are expected to become productive citizens, and the development of a compelling vocabulary encourages reading comprehension and allows people to contribute to society. Teachers have to be willing to teach students the value of improving their vocabularies in order to close the gap between the reality of the child’s life and the expectations of the child’s school (Blachowicz & Fisher, 2004). Because it can be difficult, especially for overwhelmed, new teachers, to create an effective vocabulary program, they sometimes rely on their colleagues for previously-given vocabulary tests, or they may simply use school-adopted materials (Brabham & Villaume, 2002). Teaching Vocabulary 4 “Consistently, the most common recalled vocabulary instruction centers around receiving an arbitrary list of words on Monday [and] looking up the definitions of the words in a dictionary” (Rupley & Nichols, 2005, p. 240). However, this type of word study is unproductive when the students take the initial definition and try to make sense of the word. For instance, if students took the definition of “brim” to be “edge,” they may think that, “The knife has a sharp brim,” is a logical sentence (Brabham & Villaume, 2002). Furthermore, the vocabulary words may mean something entirely different when used in another context, or the definition of the vocabulary word may contain words that the students do not recognize (Rhoder & Huerster, 2002). A similar method of instruction involves students completing drill-and-practice activities like workbook exercises, but these should not be the only strategies to teach new words (Venetis, 1999). With these word-lists/drill-and-practice approaches to vocabulary instruction, students often forget the meanings of the words and do not develop the skills necessary to use the words in their own speaking and writing. Even if memorization is mastered using this technique of instruction, that does not suggest that the students have enough knowledge of the word to apply its meaning to their own writing. Dixon-Krauss (2002) observed that even after ninth-grade students had taken their vocabulary tests, they had problems incorporating the words into writing, and their papers suffered from incorrect usage and incoherent paragraphs. Francis and Simpson (2003) reported that students were able to respond correctly to multiple-choice questions about vocabulary words, but they were not able to relate words to texts that they were reading or to write significant paragraphs. There was a need for teachers to consider another technique of vocabulary instruction that might assure students learned a word’s meaning and also how to use the word properly in speaking and writing. Teaching Vocabulary 5 Another method of teaching students vocabulary is through reading, and students who read widely have expansive vocabularies (Blachowicz & Fisher, 2004). However, all students do not read extensively, and many only read what they are required to read for school classes. Francis and Simpson (2003) reported that the average high-school student is assigned about 50 pages per week from assignments for their content courses. That number will increase to nearly 500 pages per week when that student reaches college. Additionally, by the time students reach college, professors expect them to be able to learn the text independently “because they do not have the time or inclination to discuss the information during class” (p. 66). What does this report mean for high-school teachers? They are faced with the duty of not only developing their students’ vocabularies, but also helping them create strategies to learn vocabulary on their own. “A serious commitment to decreasing gaps in vocabulary and comprehension includes instruction that allows all students to learn and use strategies that will enable them to discover and deepen understandings of words during independent reading” (Brabham & Villaume, 2002, p. 266). To approach the instruction of vocabulary through literature, teachers often choose to teach vocabulary through context. Teaching vocabulary through context simply means to look for clues in the sentence that might tell the reader something about the meaning of the word in question; furthermore, researchers have studied the impact of visual and verbal clues on learning words in context. Terrill, Scruggs, and Mastropieri (2004) studied mnemonic strategies used in vocabulary instruction for eight 10th-grade students with learning disabilities and found that using keywords with pictures that hint at a word’s meaning increased the students’ vocabulary test scores. By the end of the study, students had learned 92% of their vocabulary using this strategy compared with 49% of words learned using the word-list approach. Teaching Vocabulary 6 Several other studies have been performed that examined the contextual method of vocabulary instruction together with the word-list approach to vocabulary acquisition. DixonKrauss (2002) collaborated with a high-school English teacher to study the issue of how to improve vocabulary instruction in high school. The English teacher had noticed that her students did not retain the meanings of words they had previously learned from word lists for vocabulary tests. After the 43 ninth-grade students in that study were immersed in context-clue vocabulary study using the words in verbal and written activities, the students’ achievement scores in their journal writing increased from 65% of the words used correctly in the first assignment to 93% used correctly by the last journal entry. Dillard (2005) explored definitional and contextual methods of vocabulary instruction in four secondary English classrooms with a mixture of students in grades 10 through 12 and found that students using the contextual method of instruction outperformed the ones using the definitional, word-list approach on three of the four tests given in the study. Walters (2006) reported that improved reading comprehension resulted when 11 ESL students, ranging in age from 17 to 47, enrolled in an English language program were shown strategies of how to derive meanings of unfamiliar words from context clues. The strategy condition group in her study had the highest level of improvement in determining meanings of words. This condition entailed five steps: determine the part of speech of the word, focus on the grammar of the sentence, focus on the sentences that come before and after the vocabulary word, make a guess of the definition, and check the definition. Researchers have found that word meanings are retained longer when they are included in numerous classroom assignments. In order to really know a word, students must be able to use it in more than one context; it must be used in writing, speaking, and listening (Rupley & Nichols, 2005). Teaching Vocabulary 7 In addition to increases in achievement, researchers also found that students’ attitudes regarding their vocabulary acquisition improved from the context-clue instruction. Dixon-Krauss (2002) discovered that in the beginning of her study, students were reluctant to use the words from the context of literature into their own writing, but by the end of the study, they commented that they felt successful in using the words correctly. When the students’ teacher began another study with a different novel, the students were given the choice of writing personal essays about the reading assignments or writing summaries using at least 15 of the 20 vocabulary words. Eighty percent of the students chose to write the summaries, which, according to Dixon-Krauss, was the more difficult assignment. Francis and Simpson (2003) conducted an informal, verbal survey and were told that students did not hear their teachers use vocabulary words in class discussions, so the researchers began communicating with them using the specific words they were learning, and the students soon followed their lead. In their research study, Terrill, et al. (2004) had students voice objection to the word-list method of vocabulary and asked to use the keyword and picture approach in the future. The Study This research study was conducted in a large high school in the southern United States. In a pilot, qualitative study conducted there a year earlier, the researcher found that most students in the study were not interested in learning words for the sake of memorizing the definitions for tests and quizzes. They indicated that they wanted to have a reason for learning words; they wanted to understand how to use the words by seeing them used in context. Finally, students did not remember the vocabulary that they learned from an isolated word list because they did not use those words in their classes, and, therefore, had no reason to remember them. The results of that study indicated that students did not believe that the way they were being taught vocabulary Teaching Vocabulary 8 increased their retention of the vocabulary words. The researcher believed that teachers needed to be made aware of these student views as a means to improve the curriculum in their classes. Therefore, the researcher conducted the present study using word-list instruction and contextclue instruction. In recent years, the school at the research site underwent changes in curriculum and testing requirements. One such change was that new Georgia Performance Standards (GPS) were implemented that changed the state’s curriculum and sought to increase student performance in all academic subjects. One of the first areas in the state to be affected by GPS was the English/Language Arts area, implemented during the 2005-2006 school year. Likewise, the advent of End-of-Course Tests (EOCT), which began in the 2004-2005 school year, created a push for improvement in many academic areas. First, to coincide with the school’s improvement plan, the researcher focused on the establishment of unified and consistent curriculum within courses governed by GPS. The school’s 2006-2007 improvement plan referred to the creation of curriculum units, and the English department at the school worked to put together curriculum units that reflected that goal. However, the curriculum units fell short in the inclusion of vocabulary because the department adopted workbook-related vocabulary materials, and it had been established that the English teachers should instruct their students using those materials. The premise of the vocabulary workbooks was simple. The specific books adopted contained common words found on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), and by having the students learn these words, the teachers were preparing the students to do well on those tests. However, there was no consistent method for the delivery of this instruction, so for some teachers it became a workbook that they felt they must include in the curriculum. One English teacher stated, “I don’t like the workbooks. The students Teaching Vocabulary 9 cheat, and they don’t remember the words.” Other teachers responded similarly to questions on an informal survey regarding the current method of vocabulary instruction. Because vocabulary instruction at the research site had become more of an established routine rather than a genuine instructional encounter, this researcher wanted to develop instructional strategies that were in compliance with GPS and fulfilled the school’s improvement plan goals. Next, the state’s EOCT program influenced the school’s curriculum. For the purpose of this research, the researcher focused on the EOCT for Ninth-Grade Literature and Composition and American Literature and Composition. Before this study began, school administrators began giving these tests, first on a pilot basis, and eventually students in the ninth and eleventh grades had to take these tests in order to exit their English classes. The tests included questions from four sets of domains. For Ninth Grade Literature, the domains were reading and literature; reading, listening, speaking, and viewing across the curriculum; writing; and the convention of written language. For American Literature, the domains were similar but with an emphasis on readings in American Literature. The first two of these domains emphasized the demonstration of vocabulary knowledge and the use of vocabulary in context (Georgia Department of Education, 2004). Based on the school’s EOCT results released to the school for Fall 2005 coursework, the average score for the 417 students who took the Ninth-Grade Literature and Composition EOCT was 77%, and the average score for the 429 American Literature and Composition students was 82%. According to the EOCT Content Area Summary Report for that same semester, the two vocabulary-focused domains for both grades were quite low. Ninth graders scored 68% on the vocabulary areas whereas American Literature students scored 73%. No information was available that gave the specific number of vocabulary-related questions, but the low-test scores Teaching Vocabulary 10 coupled with the school’s need to incorporate consistent vocabulary instruction are the primary reasons for this study (Georgia Department of Education, 2006). Because “vocabulary development is a continuous process that occurs throughout an individual’s life” (Rupley & Nichols, 2005, p. 241), it is important for educators to employ strategies that foster the development of vocabulary and that keep students motivated to learn new words both in and out of the classroom. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the effectiveness of the traditional word-list approach to vocabulary instruction to literature-based vocabulary through context-clue instruction on tenth-grade students’ achievement in and knowledge of vocabulary. Definition of Variables Word-list instruction. Word-list instruction was the process of providing students with a list of words and having them use a glossary to determine the vocabulary word’s meaning. Context-clue instruction. Context-clue instruction was the process of using words and phrases surrounding the vocabulary word in the sentence as well as using structural clues in order to determine the vocabulary word’s meaning. Literature-based vocabulary. Literature-based vocabulary was vocabulary taken directly from students’ textbooks or novels for the purpose of vocabulary study. Vocabulary achievement. Vocabulary achievement was retention of the meaning of learned words and the ability to apply their meaning in context as measured by the scores of students’ tests. Vocabulary-word usage. Vocabulary-word usage was the frequency of vocabulary words used correctly in essay writing. Attitude. Attitude was the students’ opinions regarding vocabulary instruction as measured by surveys. Teaching Vocabulary 11 Research Questions Research question 1. Will context-clue vocabulary instruction using literature-based vocabulary increase vocabulary achievement compared with word-list instruction? Research question 2. Will context-clue vocabulary instruction using literature-based vocabulary cause an increase in word usage compared with word-list instruction? Research question 3. Will context-clue vocabulary instruction using literature-based vocabulary cause a difference in attitude regarding vocabulary instruction compared with wordlist instruction? Methods Participants The participants in this study were enrolled in a large high school in the southeastern United States. Of the 2,724 students enrolled at this school, 70% were White, 25% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 2% were multi-racial, and 1% was of other ethnicities. Thirty percent of the school’s population received free or reduced-price lunch, a relatively low number compared to the total student population (Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, n.d.). The 24 tenth-grade students in this study were enrolled in a gifted/honors literature/composition class. These students were of advanced ability as determined by their eighth-grade Criterion-Referenced Competency Tests (CRCT) scores and were assigned to the class by the school’s registrar. The level category of the students’ CRCT scores determined their ability level. For instance, level one CRCT scores are considered 800 or below; level 2 scores are at or above 800 but below 850, and level 3 scores are at or above 850 (Georgia CriterionReferenced Competency Tests, 2005). Because most of the students in the study made level two or level three scores, they were considered to have advanced ability and were placed in advanced Teaching Vocabulary 12 classes. EOCT scores are reported to the school divided into three groups as to how students met the GPS standards of the class. Students are given one of three comments, “fails to meet” standards (scores below 70), “meets” standards (scores between 70-89) and “exceeds” standards (scores 90 and above) (Georgia Department of Education, 2004). The students’ average eighthgrade CRCT scores and average ninth-grade Literature and Composition EOCT scores that were available are included in Table 1. Four students transferred in from other areas after the eighth grade, so there were no records of their eighth-grade CRCT scores, and two students did not have ninth-grade Literature and Composition EOCT scores. Of the students in the study, 18 (75% of the group) were White, 4 (17% of the group) were Black, and 2 (8% of the group) were Hispanic. There were 7 males (30% of the group) and 17 females (70% of the group) in the study, and the age range was 14 to17. Table 1 CRCT and EOCT Scores of Participants Test Type N M SD CRCT 20 849 12.61 EOCT 22 89 3.38 The only adult participant in the study was the teacher-researcher who taught both classes of students. This English teacher had 17 years of classroom-teaching experience at the highschool level. Intervention Introduction. The teacher-researcher began the study in the first week of the school year by explaining the study to the students and obtaining parent permissions and student consents. Teaching Vocabulary 13 The first step in the study required that students take the Student Attitude Survey (see Appendix D) to measure their attitude regarding the type of vocabulary instruction they have received in the past. When the surveys were collected, the researcher engaged the class in a conversation about their previous methods of vocabulary instruction and noted in a Teacher Research Journal the strategies that they had used to learn new words. Students were given a pretest over all 30 words from the first unit of study. They were then exposed, over the following two weeks, to two types of vocabulary instruction: word-list instruction and context-clue instruction. Students began the semester by reading William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Julius Caesar. The play contains five acts, and vocabulary words for each act were selected from the text of the play. Word-List Instruction. The teacher used word-list instruction to begin the Shakespearean unit. The list of 30 words from the play was divided in half. On Tuesday, the first 15 words were listed for students to define; students were allowed to use meanings that were provided in their textbooks in the margins of the play for these definitions. These 15 words came from the introduction to the unit and the first two acts of the play. The teacher pronounced the words for students and required them to make flashcards of the words as study aids. For homework, students were to use the words in sentences of their own. Throughout the week, students were reminded to study the words for a vocabulary test that would be given on the following Tuesday. On Wednesday, the teacher collected homework assignments, graded them, and returned the assignments on Friday. When the graded assignments were redistributed, she asked for questions regarding the assignments. On the following Tuesday, students were given The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Vocabulary Test One (VT1). Teaching Vocabulary 14 Context-Clue Instruction. After reading the first two acts of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, the teacher introduced the class to the next set of 15 words. On Tuesday students were asked to write down the words on the How Well Do I Know These Words handout, adapted from Allen (1999). Then, using a strategy derived from Center and Associates (2002), she asked the students to use structural analysis (prefixes, suffixes, root words) and prior knowledge to define any words that they already knew. The teacher then engaged the class in a short discussion of how they knew the meanings of some of the words by asking what words students had written in each of the columns on the handout. After the words were discussed, the teacher provided a second handout that included each word used in a sentence; she told the students to circle any context clues that helped them determine the word’s meaning. The teacher reviewed the students’ answers with them, and the students decided on a mutual definition of the word. Then, they checked their definitions against the ones provided in the textbook. For homework, students were to create Word in My Context (Allen, 1999) pages for the five most difficult words for themselves. On Wednesday through the following Monday, students finished reading the remaining acts of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar. As they read the remaining acts, the teacher directed them to examine the context clues that surrounded the words in the play. By Monday, students had a well-defined list of vocabulary words for the second vocabulary test. They were given The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Vocabulary Test Two (VT2) on Tuesday. To assure that each treatment received substantive attention, the researcher repeated the process for the novel unit over William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. This time, students were given 15 words from the English department’s adopted workbook-related materials to use in the word-list instruction. Context-clue instruction was designed around chapters 7-12 of Lord of the Teaching Vocabulary 15 Flies. Similar evaluations as in The Tragedy of Julius Caesar unit were used to measure vocabulary achievement. At the conclusion of the unit, all students wrote an essay regarding the tragic hero. Students were asked to choose 10 of the 30 words from the vocabulary study of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar to use in their essays. The frequency of vocabulary-word usage used appropriately from the two different instructional strategies established the vocabulary usage of the learned words. A similar essay was assigned at the conclusion of the novel unit, and the same technique was used to determine word usage. To measure the participation of the students, the teacher used the Student Observation Checklist and the Teacher Research Journal to record comments and reactions to each type of intervention. During the intervention periods, notations were made on both the checklist and in the journal. The intervention period lasted for 9 weeks. At the conclusion of the study, the teacher re-surveyed the students using a similar SAS as was used in the beginning of the study. Data Collection Vocabulary Achievement Tests (Appendix A). There were four tests, The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Vocabulary Test One, The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Vocabulary Test Two, the Workbook Unit Vocabulary Test, and the Lord of the Flies Vocabulary Test. Each test included 15 matching questions where students were required to match the definitions with the correct vocabulary words and 15 problems in a fill-in-the-blank section where students had to use context clues to determine the missing word in the sentence. Vocabulary tests were administered to all students before and after each form of instruction. The pretests contained matching items only, whereas the posttests contained the matching items as well as the fill-in-the-blank items. The teacher measured the content validity of the tests by having them peer reviewed by four Teaching Vocabulary 16 other teachers prior to administration. Reliability was achieved using the same form of the test and using the words that were selected in the literature studied. Students received a grade giving percentage correct, which was the method of scoring. Scores were analyzed by using one-tailed paired t-tests. These results were interpreted by comparing mean gains for the word-list instruction against mean gains for context-clue instruction. The Tragic Hero Essay (Appendix B). This essay assignment was designed to measure students’ knowledge of the words they had learned in the vocabulary instruction of the unit by their use of written compositions. After each unit of instruction, students wrote compositions relating the main character studied to the qualities of a tragic hero. They were required to use at least 10 of the learned vocabulary words, and the teacher measured their achievement by calculating the number of words used correctly. The validity of this constructed-response assignment was measured by being peer reviewed by four other teachers. The teacher used a rubric to grade the assignment and those scores were converted into percentage correct. By counting the number of words used from word-list instruction and counting those used from context clue instruction, the researcher compared the results. She calculated percentages of word usage for each category to determine the method of instruction from which the students used more words. Student Observation Checklist (Appendix C). An observation instrument in a checklist format helped the teacher to determine which method of instruction received the most reaction from the students by measuring their positive or negative participation in the activities assigned with both interventions. This instrument provided a way to note students’ on-task behavior, level of engagement, and peer interaction. These behaviors, for example, could be complaints about assignments and activities or positive comments about doing similar assignments in other Teaching Vocabulary 17 classes. The checklist was used four times, twice during each intervention. The checklist was peer reviewed for construct validity by four other teachers prior to being used in this study. Results were interpreted by calculating the number of positive reactions the word-list instruction received as opposed to the number of positive reactions the context-clue instruction received. The teacher calculated the percentages of positive and negative reactions each assignment received to use as data to answer the question about student attitudes. Student Attitude Survey (Appendix D). The Student Attitude Survey (SAS) asked students to give their opinions regarding the way they had received vocabulary instruction in the past. Prior to the study, students were asked to respond to 8 Likert-type statements that asked for their degree of agreement or disagreement about their ninth-grade vocabulary instruction. At the end of the vocabulary instruction for the novel unit, the teacher re-surveyed the students with a similar SAS to see if there was any change in attitude. The SAS was peer reviewed by four other teachers prior to being administered to the students to check for construct validity. Responses were scored from 5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree. To analyze responses, the researcher collapsed the categories into three groups. Categories of responses were strongly agree/agree, undecided, and disagree/strongly disagree. After responses were tallied, percentages were determined for each category and for each question. These percentages helped the researcher determine the method preferred by the students in the research study. Teacher Research Journal. During the course of the study, the teacher kept her own personal record of comments made by students and their opinions regarding the interventions. The journal contained daily accounts of class observations and student remarks made about the two methods of study. This information was later used to help to interpret participation and to provide data for triangulation of results. Teaching Vocabulary 18 Results Five instruments were used to measure the research comparing word-list vocabulary instruction to context-clue vocabulary instruction. To measure results quantitatively, the researcher gave students vocabulary achievement tests over words in two literature units, and she required them to write essays that included words from the vocabulary groups that they had studied. To gather results both quantitatively and qualitatively, the researcher had the students answer questions from surveys, and she kept observation checklists to monitor their involvement in vocabulary activities. As a means of qualitative research, the researcher kept her own journal where she recorded various comments made by the students regarding the research study. The first analysis was an evaluation of test results over the words in two units of study. After discussing the research project with students, the researcher gave students a pretest over 30 words in The Tragedy of Julius Caesar unit. Upon completion of both learning strategies, students took tests over those particular words. Means and standard deviations for all tests are given in Table 1. Table 1 Comparisons of Vocabulary Test Results for The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Unit Tests N M SD Pretest 24 53.83 16.87 Word-List 24 96.08 5.75 Context-Clue 24 97.79 4.96 t-value P -1.10 0.14 * p < .05; ** p < .01 Means and standard deviations for the pretest indicated that most students knew about half of the words in the unit. After students were exposed to both types of instruction, the mean vocabulary test score after word-list instruction was not significantly different (t (46) = -1.10, Teaching Vocabulary p = 0.14) from the mean vocabulary test score after context-clue instruction. An analysis of other tests of vocabulary achievement indicated similar results. Students took tests over SAT workbook words that were studied using word-list instruction and over words from the latter chapters of Lord of the Flies that were studied using context-clue instruction. Means and standard deviations for both tests are given in Table 2. Table 2 Comparisons of Test Results for Novel Unit Tests N M SD t-value P SAT Workbook Lord of the Flies * p < .05; ** p < .01 24 85.29 21.18 0.30 0.38 24 83.62 16.29 Though the means and standard deviations vary from those in Table 1, there was no significant difference (t (46) = 0.30, p = 0.38) between the mean scores for either test in the novel unit. Therefore, results of both sets of test scores indicated that there was no significant difference in achievement between the two methods of instruction. Percentages Percentage of Word Usage 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Caesar 1 Caesar 2 Workbook Word List Groups Figure 1. Percentage of Words Used in Essays Novel 19 Teaching Vocabulary 20 To determine whether one instructional strategy was more effective than the other in increasing usage of new vocabulary words, the researcher measured students’ preference of word choice when writing essays. The researcher assigned tragic hero essays at the conclusion of both units, and students chose 10 words from each unit to include in their essays. Percentage results for the four groups of word choices are shown in Figure 1. Results show a preference in word choice of words learned through context-clue vocabulary instruction. In the first group of results from The Tragedy of Julius Caesar unit, students selected 10% more words from context-clue instruction than from word-list instruction. In the novel unit, the percentage rose to 24% more context-clue words used than word-list words. Therefore, calculations of percentages from all four word groups indicate that vocabulary instruction using context-clue instruction can cause an increase in word usage compared with word-list instruction. The researcher also kept Student Observation Checklists as they worked on the various assignments given for each type of instruction. These checklists were used each time a new set of words were introduced to the class. The researcher checked to see if students were on task, following directions, and interacting with their peers. Results of percentages for each category are given in Table 3. Table 3 Comparisons of Observation Results Instruction Type Percent On Task Word List 100 Percent Following Directions 100 Context Clue 100 100 Percent Interacting with Peers 52 64 Teaching Vocabulary 21 Although all students were on task and followed directions while working on assignments for both instructional strategies, 12% more students interacted with their peers while completing context-clue assignments. More students were willing to share their thoughts and ideas regarding the words learned through context clues than those learned through word lists. These results may indicate a difference in attitude between instructional strategies because students had more to say about context-clue instruction than word-list instruction. To assess student attitudes regarding their preference of instruction, the researcher administered the Student Attitude Survey (SAS), which indicated that students felt a need for another method of learning vocabulary instead of the SAT workbooks that they have used in the past. Nearly half of the class (46%) believed that vocabulary instruction needed improvement in their literature classes. When asked about using dictionaries to locate unknown or difficult words, 50% of the class responded that they do use dictionaries, but 92% said that they also rely on context clues to find vocabulary meanings. Upon engaging the tenth-grade students in a conversation regarding past vocabulary instruction, both in the ninth-grade and in middle school, the researcher noted that students rarely recalled words from their previous SAT workbooks. They commented that the words “went over their heads” and that type of vocabulary learning was “pointless.” At the conclusion of the study, students completed another SAS and responded to similar questions as those they answered in the first SAS. Students responded that if given a choice of vocabulary instruction, 78% of them would choose to learn words in context from the literature being studied. Only 22% of the class stated that they would keep the SAT workbooks, and most of them commented that they liked the definitions that the workbooks provided, which meant they did not have to determine the meanings themselves. According to the first SAS, most Teaching Vocabulary 22 students already used context clues to determine word meanings; therefore, the results of the two surveys did not indicate that their attitudes about context-clue instruction changed as a result of the study. The final instrument used by the researcher was the Teacher Research Journal. Every day that the class was involved with activities from the research study, the researcher recorded comments that she would later use as indicators of student attitude. She also used the journal to record her own comments about results of class assignments, such as what words students had the most trouble with in each instructional method. These comments were useful in gathering qualitative data to use in discussing the students’ attitudes. The researcher noted that she had more interaction with the class on the days that she instructed them through using context clues, which may indicate their preference with this method of instruction. When students began the second vocabulary unit, many voiced their opinions about the study of the SAT word lists. Several students made such comments as, “I’ve never heard these words before” and “We’ll never use these words again.” Some students did not interact as well when doing assignments related to word-list instruction as they did when they worked on context-clue instruction. They tended to sit quietly and prepare their flashcards over the word-list group; only a few students provided their classmates with strategies for learning these words. However, when the researcher introduced the second context-clue list to students, she had more comments regarding the familiarity of the words. For example, students participated with one another and the researcher when they found the 15 words in Lord of the Flies that they highlighted and defined in context. One student noted that the word “abominable” was much like “abomination,” and she knew that “abomination” meant “an evil act.” After Teaching Vocabulary 23 reading the words as they were used in the novel, students indicated a greater understanding of the definitions. Discussion Conclusions The research did not show that context-clue vocabulary instruction using literature-based vocabulary caused an increase in vocabulary achievement compared with word-list instruction. Students’ overall test performance was similar using both instructional approaches. Results from this research agree with that reported by Dixon-Krauss (2002) and Francis and Simpson (2003). Students in those studies were able to do well on tests over vocabulary words, but they did not achieve as well when asked to use the words in the context of writing. Students in the present study, however, were given a choice of which vocabulary words to use, so unlike the other studies, students were not told which words to use. The research showed that context-clue vocabulary instruction using literature-based vocabulary did cause an increase in word usage compared with word-list instruction. After instructional strategies were used for both methods of learning, students were assigned essays regarding the tragic heroes in two separate literature units. They were told to choose words to use in their essays from all words studied in the unit. More students chose words from the contextclue groups than from the word-list groups. Studies performed by Dixon-Krauss (2002) and Dillard (2005) produced similar results. By showing students various strategies to learn words with context clues, students in those studies were able to perform better on written assignments. The research showed that context-clue vocabulary instruction using literature-based vocabulary did cause a difference in attitude regarding vocabulary instruction compared with word-list instruction. Student opinions voiced in surveys and verbal comments were more Teaching Vocabulary 24 favorable toward context-clue instruction than word-list instruction. Dixon-Krauss (2002) and Terrill, et al. (2004) experienced similar attitudes. Students in those studies voiced opposition to word-list instruction and asked for more meaningful methods to learn their vocabulary. Significance/Impact on Student Learning The results of the study indicated that when students have a voice in the method of instruction, they might perform better on certain assignments. Students in this study made it clear to the researcher that they wanted a meaningful method to learn vocabulary, and they wanted to learn words that have significance to the literature that they are reading. Though the achievement of student test scores did not show a significant difference between the two methods of instruction, the other data-collection instruments showed that students were partial to contextclue instruction. Students chose more words from context-clue instruction than word-list instruction when given the choice of which words to use in their essays. Their choice of words is an important element to consider when determining which instructional method is more apt to cause word retention. For years, the English department at the study school has used SAT workbooks and other vocabulary workbooks as its method for vocabulary instruction. The results of this study indicate that this method of instruction is not favorable to students, and they prefer vocabulary to come from the literature that they read instead of from arbitrary word lists. Students in this study showed a preference for words taught through context clues, which may explain their greater use of these words in their writing and indicate their probability to use the words in their own vocabularies. Teaching Vocabulary 25 Factors that Influenced Implementation One of the main factors that influenced the implementation of the study was that the English department did not receive their newly adopted textbooks for the first three weeks of the semester. Students in the study were given a paperback copy of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar to read until the textbooks arrived. The paperback copies did not have the vocabulary words emphasized as the textbooks did, so the researcher had to identify the words for them. The other factor that influenced the implementation of one of the instruments was the time in which the last vocabulary test over the novel unit was administered. The school was celebrating its Homecoming week, and the last test was scheduled for a day in which most of the students were absent due to preparations for the Homecoming parade. Because so many students would have to make up the test, the researcher decided to give the test, originally scheduled for Thursday, on the following Monday. Implications & Limitations One limitation to the research was that the class size was relatively small for an extensive study of vocabulary. A sample that included two classes would have given the researcher more results and a wider variety of students. The 24 students in the study, mostly female, did not show a wide range of results when it came to the achievement data. Another limitation to this study was the ability level of the class. Because they were all classified as advanced students, several students had much prior knowledge of the words in both interventions. Furthermore, they tended to study to a greater extent, and that may be attributed to their ability level. For instance, even though they were not required to make flashcards for the context-clue word groups, may students did as a way to prepare for the tests. Teaching Vocabulary 26 A final limitation to this study was the fact that the researcher was also the teacher of the students. Obviously, the teacher-researcher had a vested interest in the results, and there could be instances where certain comments were not recorded in her journal and other, more favorable to the study, were recorded. For the most part, however, this was not the case, and comments were recorded that were favorable and unfavorable to the study. Implications of the study were that students wanted to learn words that were meaningful to them. Studying vocabulary for the sake of learning new words is not what they considered important. Because vocabulary instruction has been taught the same way for many years at the research site, the researcher shared her findings with the English department. The researcher’s colleagues need to find ways to actively involve their students in the study of vocabulary and to make vocabulary instruction meaningful for them. Similar procedures could be useful for education in general. Regardless of what teachers ask of their students, some, as was the case in this study, will perform well no matter how they view the instruction. However, in order to have more successful students across the board, teachers should first consider the needs of their individual students. Teaching Vocabulary 27 References Allen, J. (1999). Words, words, words: Teaching vocabulary in grades 4-12. Portland, ME Stenhouse Publishers. Blachowicz, C., & Fisher, P. (2004). Vocabulary lessons. Educational Leadership, 61(6), 66-69. Brabham, E. G., & Villaume, S. K. (2002). Vocabulary instruction: Concerns and visions. The Reading Teacher, 56(3), 264-268. Center and Associates (Producer). (2002). Reading and writing in the content areas: Strategies for building literacy, module 4 vocabulary strategies [Motion picture]. (Available from Center and Associates, P.O. Box 66926, Los Angeles, CA 90066-6926) Dillard, M. (2005, December). Vocabulary instruction in the English classroom. Studies in Teaching 2005 Research Digest, 21-25. Dixon-Krauss, L. (2002). Using literature as a context for teaching vocabulary. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 45(4), 310-318. Francis, M. A., & Simpson, M. L. (2003). Using theory, our intuitions, and a research study to enhance students’ vocabulary knowledge. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 47(1), 66-78. Georgia Criterion-Referenced Competency Tests (2005). CRCT Score Interpretation Guide [Electronic version]. 1-42. Georgia Department of Education (2004, June). Georgia EOCT Interpretation Guide for Score Reports [Electronic version]. 1-28. Georgia Department of Education (Winter, 2006). Georgia End-of-Course Tests System Content Area Summary Report. Released to research site. Teaching Vocabulary 28 Governor’s Office of Student Achievement. (n.d.) 2005-2006 k-12 public schools annual report card. Retrieved March 8, 2007 from http://reportcard2006. gaosa.org/k12/Accountability.aspx?TestType=acct&ID=692:5050 Manzo, A. V., Manzo, U. C., & Thomas, M. M. (2006). Rationale for systematic vocabulary development: Antidote for state mandates. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 49(7), 610-619. Rhoder, C., & Huerster, P. (2002). Use dictionaries for word learning with caution. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 45(8), 730-736. Rupley, W. H., & Nichols, W. D. (2005). Vocabulary instruction for the struggling reader. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 21(3), 239-260. Terrill, M. C., Scruggs, T., & Mastropieri, M. (2004). SAT vocabulary instruction for high school students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 39(5), 288294. Venetis, A. (1999). Teaching vocabulary: Within the context of literature and reading or through isolated word lists. Unpublished master’s thesis, Kean University, Union, NJ. Walters, J. (2006). Methods of teaching inferring meaning from context. Regional Language Centre Journal, 37(2), 176-190. Teaching Vocabulary Appendix A The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Vocabulary Test One Directions: Use the answer sheet provided to record your answers to the following sections. Matching: Choose the letter of the definition that best matches the vocabulary word. VOCABULARY WORDS [1] integrity DEFINITIONS [a] about to occur [2] superficial [b] honesty [3] credible [c] with intense anger [4] prodigious [d] a duplicate [5] replication [e] believable [6] servile [ab] rebellion [7] spare [ac] shallow; concerned with the obvious [8] infirmity [ad] strong determination [9] portentous [ae] of great size or power [10] entreat [bc] enhance [11] imminent [bd] lean; thin [12] resolution [be] beg; plead [13] insurrection [cd] weakness; physical defect [14] augment [ce] humbly submissive to authority [15] wrathfully [de] giving signs of evil to come 29 Teaching Vocabulary 30 Fill in the Blank: Choose the letter of the vocabulary word that best completes the following sentences. [a] integrity [b] superficial [c] credible [d] prodigious [e] replication [ab] servile [ac] spare [ad] infirmity [ae] portentous [bc] entreat [bd] imminent [be] resolution [cd] insurrection [ce] augment [de] wrathfully [16] His __ made it impossible for him to take part in athletic activities. [17] Some people believe it is __ that an ancient water monster lurks at the bottom of Loch Ness. Her __ to give up smoking lasted two days. [18] [19] [20] [21] The two weeks of steady rains __(ed) the water in the swimming pool until it was nearly overflowing. The way in which she __ shook her fist at the driver in front of her indicated her anger. The suit was not tailored for someone with a __ build like his. [22] [23] Many pregnant women have __ appetites and believe they are eating for two people. His __ behavior toward our employer makes me uncomfortable. [24] “Now I pronounce you man and wife” is the phrase that means a kiss is __. [25] The attorney __(ed) the jury to examine the evidence and find his client innocent. [26] [27] Some feminists believe that beauty contests are __ competitions that are intended for a man’s pleasure. The opened, unlocked door was a __ clue that the apartment had been invaded. [28] The art collector bought an expensive __ of one of Monet’s pieces. [29] Her thorough resume and faultless __ made her an unbeatable candidate for the new position. The army’s __ caused absolute chaos in the country. [30] Teaching Vocabulary The Tragedy of Julius Caesar Vocabulary Test One Answer Key [1] b [16] ad [2] ac [17] c [3] e [18] be [4] ae [19] ce [5] d [20] de [6] ce [21] ac [7] bd [22] d [8] cd [23] ab [9] de [24] bd [10] be [25] bc [11] a [26] b [12] ad [27] ae [13] ab [28] e [14] bc [29] a [15] c [30] cd 31 Teaching Vocabulary 32 Appendix B “The Tragic Hero” Essay Instructions Many of William Shakespeare’s characters meet the qualifications of a tragic hero as defined by the Greek philosopher Aristotle. Your task is to see if Marcus Brutus also meets those qualifications. Directions: [1] Using your knowledge of the play as well as the characteristics of a tragic hero, decide if Brutus falls into the category of a tragic hero. First, using the address given for Defining a Tragic Hero above, find the qualities of the tragic hero. Next, note the qualities that are characteristics of Brutus. Find evidence in the play (act, scene, and line numbers) that corresponds to each of the characteristics that you have chosen. [2] Review the information on writing analytical papers at the address for A Guide to Writing Analytical Essays. Note the information that is needed in the introduction, body, and conclusion. Choose three tragic hero qualities to discuss in the essay, and write the rough draft following the directions given at this website. When you develop the body of the essay, be sure to quote the lines from the play accurately by following the guidelines provided at the Quoting Shakespeare website. [3] Review the rough draft and edit it according to the suggestions provided at the Editing and Proofreading Tips page. Carefully edit your paper; then compose the final draft. Proofread the final draft as well. Additional Directions: [1] Use at least 10 of the vocabulary words that you learned from this unit in your essay. Underline them in the final copy. [2] Essay titles should be informative, creative, and original. [3] Final copies need to be typed (Times New Roman, 12 font) and in MLA manuscript form. [4] The essay will be scored as a test grade; see the attached rubric for scoring criteria. ESSAY DUE DATE: ________________________________________________________________ Teaching Vocabulary 33 “The Tragic Hero” Essay Rubric Student Name: ________________________________________________________________ Essay Title: ___________________________________________________________________ 40 points Content 20 points Movement 15 points Writing Style 15 points MLA Manuscript Form 10 points Grammar/Spelling/ Punctuation/Mechanics Total Score: __________ The essay is on topic; it provides background information as well as adequate and reliable evidence to support tragic hero qualities. The essay moves logically from one point to the next; ideas are linked by transitions that are provided throughout the paper. The writing is a mature style that includes a variety of sentence types and sentence lengths. Word choice is logical and includes usage of newly acquired vocabulary. All required areas of MLA manuscript are completed accurately. The essay is free of errors in grammar, spelling, punctuation, and mechanics. Teaching Vocabulary 34 Appendix C Student Observation Checklist _____ Word-List Instruction _____ Context Clue Instruction Assignment: _____________________________________________________________ Date: ___________________________________________________________________ Student On-Task Following Directions Interacting with Peers Teaching Vocabulary 35 Appendix D Student Attitude Survey The following survey will be used to evaluate student opinions of two vocabulary-learning methods. This information will be used in data collection for my research project at Valdosta State University. Students are not required to participate in the survey. Directions: Using the following scale, rate each statement according to your degree of agreement or disagreement. SA = strongly agree A = agree U = undecided D = disagree SD = strongly disagree SA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 I learn vocabulary words easily when they are taught separately from literature. I find it easy to remember vocabulary words when I look for the meaning in a dictionary or glossary. When I am reading and come to a word that I do not know the meaning of, I use context clues in the sentence to figure out the word’s meaning. When I am reading and come to a word that I do not know the meaning of, I use a dictionary to figure out the word’s meaning. After taking a test over vocabulary words from the vocabulary workbooks, I often use those words in my own speaking and/or writing. After taking a test over vocabulary words from the vocabulary workbooks, I often forget the words. Overall, I am satisfied with the amount of words I can remember from the vocabulary workbooks. I believe another method of vocabulary instruction might be helpful in order for me to retain more vocabulary. A U D SD