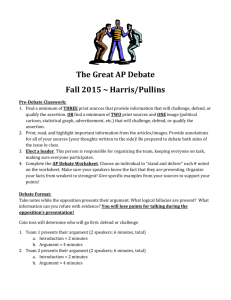

Relativism, Assertion, and Belief

advertisement