Texas English

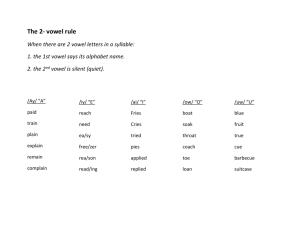

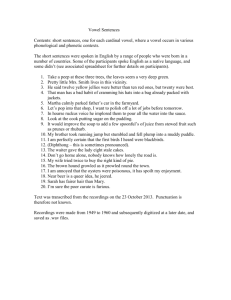

advertisement

Texan and Californian: Variation at state level 1.1 TX English (TXE) in general --Popular imagination :oil and cowboys, glitzy modern cities and huge isolated ranches (fueled to a large extent by the size of the state, its portrayal in television shows such as Dallas and in movies such as Giant ) --TX was an independent nation before it became a state, having had its own Revolutionary War and creation story > TX English (TXE) is often assumed to be somehow unique too. >< Yet, only a few features of TXE do not occur somewhere else. Nonetheless, in its mix of elements both from various dialects of English and from other lg-es, TXE is somewhat different from other closely related varieties. (Ill.: Cowboy talk DYSA2 21:36-27:36 > 6 min) 1.2 A short linguistic history of TX --historically, English is the second language of the state --Spanish was spoken in TX for nearly a century before English was. --the opening up of TX to Anglo settlement in the 1820s, and the continuing influx of settlers from 1836 to the beginning of the twentieth century enhanced and transformed the mix. --Anglos from both the Lower South (Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina) and the Upper South (Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, and North Carolina) > Lower Southerners generally dominated in east and southeast TX and Upper Southerners in the north and central parts of the state, + there was considerable dialect mixing. --Migration (1910-1920) and new immigration (since 1990) from Mexico has been massive --This complex dialect situation was further complicated, especially in southeast and south central TX, by significant direct migration from Europe (Germans, Austrians, Czechs, Italians, and Poles) > the confluence of influences --AAE (Ill.: AAE in TX DYSA2 27:36-35:36 > 8 min) 1.3 Some Characteristics of TX English --due to settlement history, TXE is a form of Southern American English w/ many of the lexical, grammatical, and phonological features thereof >< As a result of the complex settlement pattern, however, the South Midland/Southern dialect division that divided areas to the east was blurred in TX. Throughout the history of the state, South Midland lexical items (e.g., green bean and chigger) and phonological features (e.g., post-vocalic /r/ in words like forty and intrusive /r/ in words like warsh) have coexisted and competed with Southern words (e.g., snap bean and redbug) and pronunciations (“r-lessness” in words like forty and four), although Southern features were and still are strongest in east TX. --In south, south central, and west TX, a substantial number of Spanish words gained general currency. (Ill.: TX Towns and writers DYSA2 35:36-40:05 > 4:30 min) 1.3.1 Lexical items --general currency of Spanish words like canyon, corral, fiesta, and lasso (reflecting the relatively large number of Hispanics in the area, but also the importance of Mexican American culture in the development of a distinct TX culture. --fixin’ to (as in, “I can’t talk to you now; I’m fixin to leave”) --items originating from or having their greatest currency in TX (e.g., tank ‘stock pond,’ maverick ‘stray or unbranded,’ calf, doggie ‘calf,’ and roughneck ‘oil field worker’) --a skunk is called a “pole-cat,” and milk that is about to turn sour is “blinky” ---the petroleum industry is the “all bidness” --a soft drink is either “a soda” or “a Coke, even if it’s Dr Pepper” 1.3.2. Grammatical features --y’all (plural or singular, too?) --perfective done (as in “I’ve done finished that”). --multiple modals like might could (as in, “I can’t go today, but I might could go tomorrow”) 1.3.3 Pronunciation --the “vowel merger” of sounds: words like “win” and “when” or “pin” and “pen” sound alike, (a dime is called “tin cints”) as do “cot” and “caught,” “feel” and “fill,” --vowels seem to stretch on forever --flattening of words, where ‘fahr’ is spelt as “f-a-r” but also as “f-i-r-e” (‘Look, that damn house is on fahr.’ ‘How fahr is it over there?’) --the upgliding diphthong in dog (often rendered in dialect literature as dawg) --trademarks of Southern English phonological features: -the pen/pin merger (both words sound like the latter) -the loss of the offglide of /ai/ in words like ride and right (sounding like rahd and raht) -barbed wire sounds like “bob wahr” and night sounds like “naht” --while at least one traditional pronunciation, the use of ar in words like horse and for (this makes lord sound like lard), occurs only in TX, Utah and a few other places --BUT harder than the “syrupy” Southern accent: keeps the r-s in ‘mother’ and ‘father’ --3 kinds of vowel systems: New York—the Northern Cities Chain Shift (‘bad’ sounds like ‘bid’ and ‘dog’ like ‘dooaug’) South—the Southern Shift (‘wait’ sounds like ‘wuhate’) West—the Third Dialect (merger of the vowel in ‘caught’ and ‘cot’) In TX—a combination of the Southern Shift and the Third Dialect makes TX distinct: > a soft, musical drawl of East TX > a more clipped rhythm of Central TX > a flat, nasal twang typical of Southern TX. (Audio Ill.: TX Twang NPR 2:52 min) 1.4 Change and Persistence in TX Speech --Rapid metropolitanization, increasing dominance of hi-tech industries, & massive migration (~ 1/3 of the population lives in the Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio metro areas) --non-native Texans make up an increasingly large share of that population. > a metropolitan, diverse, high-tech state—with significant linguistic consequences. --the most obvious one is an emerging rural-urban linguistic split: The pen/pin merger, the loss of the of the offglide in /ai/, and upgliding diphthongs in words like dog are now recessive in metropolitan areas, although the first two in particular persist elsewhere. The urban-rural split is so far largely a phonological one, though. Both y’all and fixin to are expanding to non-natives in metropolises (and to the Hispanic population too). Those grammatical features that are disappearing in metropolises (e.g., perfective done) seem to be disappearing elsewhere as well. > What seems to be emerging on the west TX plains, then, is a dialect that combines features of Southern speech and another major dialect. (Ill.: TX: Language and Politics DYSA2 40:05-45:25 > 5:20 min) --people who are proud to be Texan are proud to talk like Texans. 2.1 Cal(ifornia) English in general (direction of influence traffic) (Audio Ill.: California / Eckert NPR) 2.2 Stereotypes (Frank & Moon Unit Zappa, “Valley Girl,” ca 1982): ~s and Surfer Dudes. >< the real Cal, with a population of nearly 34 million, is only 46.7% white (most of whom are not blond and don’t live anywhere near the beach); + a large Latino population that accounts for 32.4% of the state’s total numbers (Chicanos) + home to a large Chinese-Am and Japanese-Am population: 11.2% Asian-American + most of the sizeable African-American population (16.4%) in Cal speaks a form of African-American Vernacular English, with few traces of surfer dude or valley girl. (Ill.: Southern Cal’s Valley girl speech persists (1:51 min) 2.3 Linguistic style (is inseparable from clothing style, hair style, and lifestyle) --stereotypic accent (Ill.: Movies, California and Prestige DYSA3 15:05-22:25 > 7:20 min) --the vowels of hock and hawk, cot and caught, are pronounced the same > so awesome rhymes with possum. --the movement of the vowels in boot and boat forward in the mouth, so that the vowel in dude or spoon (as in gag me with a…) sounds a little like the word you, or the vowel in pure or cute --boat and loan often sound like bewt and lewn—or eeeeuuw. --the vowel in but and cut is also moving forward > these words sound more like bet and ket << all part of the commonly imitated Cal surfer speech. (Ill.: Valley Girl and Surfer Dude DYSA3 22:25-30:00 > 5:20 min) 2.4 Vowel shifts that go by almost unnoticed: --the vowel of black often sounds more like the vowel in block, the vowel of bet is moving into the place of bat, and the vowel of bit is moving into the place of bet --the chain shift occurring in Cal, although relatively early in its progress, will have a lasting effect on the system, eventually resulting in significant differences from other dialects. 2.5 Quotatives: --the use of the discourse marker “I’m like,” or “she’s like” to introduce quoted speech, as in “I’m like, ‘where have you been?’” --particularly useful because it does not require the quote to be of actual speech (as “she said” would, for instance). A shrug, a sigh, or any of a number of other expressive sounds as well as speech can follow it. --Lately in Cal, “I’m all” or “she’s all” has also become a contender for this function. > the quotative “be all” is not common in the speech of young New Yorkers, for example, while “be like” is. (Ill.: Other Board-Speak DYSA3 30:00-33-40 > 3:40 min) 2.6 Why is it that some groups have ethnic linguistic varieties (such as Chicanos) and others (such as Japanese-Americans) do not? --Cal English is a reflection of politics, history and intersecting communities…assimilating to the speech of the white majority was a linguistic consequence of the catastrophic events in their community.