report - University of York

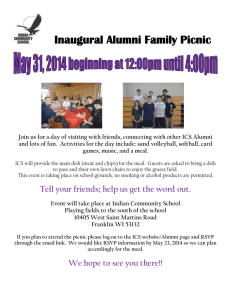

advertisement