Computer notes:

advertisement

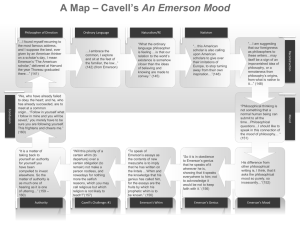

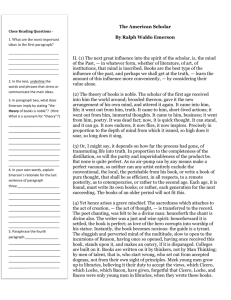

The American Scholar: Emerson’s Declaration of Independence I find it especially appropriate to speak today on Emerson’s “American Scholar” address and to approach it as his declaration of independence since we are just finishing the season of college graduation speeches and also find ourselves exactly one month from the 4th of July. His speech, the annual Phi Beta Kappa address, was actually delivered the day after Harvard’s commencement at the end of August 1837, but, for all intents and purposes, can be called a graduation talk, since it was attended by students, faculty, including those of the theological School, and the Fellows of the Harvard Corporation, i.e. the overseers of the college. Emerson’s statement on the nature and duties of the American scholar, furthermore, is nothing other than a full-throated call for his auditors to liberate themselves from what William Blake dubbed “the mind-forged manacles.” The AS stands as the center piece of 3 works produced in quick succession by Emerson, which, taken together, represent his first enunciation of the Transcendentalist vision: “Nature” (1836), AS (1837), and “The Divinity School Address” (1838). In actuality, the subject of the American Scholar that is, the qualities defining such a person, had been the traditional and prescribed theme for some years before Emerson’s presentation. What set his talk apart from the earlier ones were the radical, indeed, the subversive, departures from the well-worn and predictable script. As I used to tell my students, don’t let the man’s frock coat and cravat deceive us. He was a radical and those in attendance that day weren’t long in recognizing that fact. As might be expected, the young members of the audience were particularly receptive to Emerson’s message. Bliss Perry, a novelist, critic, and revered Harvard English professor wrote, in the 1920’s, a remarkable essay in which he reconstructed from primary accounts the vibrant scene of the occasion , including the detail that a substantial rain had fallen in Cambridge the previous day. 2 Perry, after identifying some of the faculty present in the audience, many of whom had been Emerson’s teachers during his time as an undergraduate and as a student in the theological school, proceeds to note that “amid all the learning and fashion and beauty which throng the meeting house, do not overlook the eager boys—for their ears catch overtones and undertones which are unperceived by their elders.” Perry postulates that although available sources do not say, Thoreau, still at this time answering to David Henry, instead of Henry David, might have been in attendance, since he had graduated the day before and might have lingered to hear his older Concord neighbor and mentor hold forth. We do know that two young men who were in attendance carried the memory of Emerson’s presentation well into their later lives. One of these was Oliver Wendell Holmes, father of the famous Supreme Court justice, and a successful physician, poet, and essayist in his own right. Years later he cited “this grand Oration” as being “our intellectual Declaration of Independence. Nothing like it had been heard in the halls of Harvard since Samuel Adams supported the affirmative of the question, ‘Whether it be lawful to resist the chief magistrate, if the commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved.’ ‘’ The other young man, a classmate of Thoreau, was James Russell Lowell, who himself was later to become a prominent poet and popular member of the Harvard faculty. He recalled much later: “The Puritan revolt had made us ecclesiastically and the Revolution politically independent, but we were socially and intellectually moored to English thought, till Emerson cut the cable….His oration before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge, some thirty years ago, was an event without any former parallel in our literary annals, a scene to be always treasured in the memory for…its inspiration.” Significant is Lowell’s suggestion that it was the young listeners who caught the meaning of Emerson’s words, implying that the older members of the audience, faculty and overseers, the academic establishment if you will, were visibly resistant to the speech. Perry himself concludes most of the dignitaries greeted the address with equal parts shock and 3 mystification. Such a reaction by this distinguished company ishould not in retrospect, be surprising when we look at the particulars of the case that Emerson presents. Although Holmes and Lowell chose to see the theme of the AS as being a plea for the cultivation of an indigenous arts and literature, no longer subordinate to English models, that view, I believe, is giving too much weight to Emerson’s opening gambit with its oft quoted declaration: “Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close.” Holmes’s and Lowell’s focus has been given undue play by later commentators. My suspicion is that Emerson inserted this statement at the outset of his address as a rhetorical bow to what had become, in essence, the expected sentiment to voice on such occasions as this one, an early equivalent basically of “Buy American” bumper stickers. Emerson made the point in order to be done with it so he could quick march to the points he really wanted to dwell on. When we look at the AS, we need to recognize Emerson’s real topic, the formation of the self-motivated individual, the person who thinks and acts in the now, taking from the past only that which authenticates his present experience. The AS then is a foundational statement of Emerson’s Transcendental philosophy, building on his Nature essay of the previous year and prefiguring the Divinity School Address which was to follow in the next , this latter utterance leading to his being denied any official invitation to the Harvard grounds for about the next 25 years . I can’t this morning summon up the requisite glibness to supply a catchy definition of Transcendentalism, so I will defer to Emerson, who, on one occasion, when asked to summarize his creed, said that it could be boiled down simply to a belief in “the infinity of man.” I don’t think Emerson would object any if we added “and woman.” The body of the AS concerns itself with what Emerson identifies as the three influences which, if actively sought out and responded to, will lead to the scholar’s 4 liberating himself from the mental and spiritual submissiveness which holds him back from that boundless potential he needs to reclaim. These influences are: 1) Nature, 2) “the mind of the past”, and 3) “The world…that lies wide around.” There can be little doubt, even in the absence of a video record that Emerson from about this juncture to the end of his discourse locked his gaze on the young men in the audience who, as at all commencements, were ready to enter upon their life pursuits. Which probably explains why even before bringing out the all-important trinity of influences, he warns of the daunting prospect he sees before them of a society “in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters,--a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.” Emerson is essentiallyexpanding on his memorable assertion in the Nature essay that “Man is a god in ruins.” He is in this broken state because he has shrunk himself to fit his chosen vocation, his particular line of work. He has, in effect, been reduced to a function. Thus, says Emerson,“The priest becomes a form, the attorney a statute-book; the mechanic, a machine; the sailor a rope of the ship.” Then Emerson delivers the cruelest cut of all, aimed, it is certain, at some of his former teachers, now visibly fidgeting in their seats: “In this distribution of functions the scholar is the delegated intellect. In the right state he is Man Thinking. In the degenerate state, when the victim of society, he tends to become a mere thinker, or still worse, the parrot of other men’s thinking.” If wholeness or integration of the human being’s squandered powers is to be recovered, Emerson says the one who aspires to the status of American Scholar, must properly engage the three aforementioned influences. Nature is the first of these. For Emerson, it is the quintessential source of the individual’s empowerment. Behind its diverse forms moves what he elsewhere calls the “universal soul” or, more often, the “Over-Soul.” To look into nature, therefore, is to look into one’s own soul which is tributary to this larger soul: “ He 5 shall see that nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal and one is print.” We can assume further fidgeting at Emerson’s blissful pronouncement, this time from the section reserved for the faculty of the theological school. They would have now clearly scented in the air the brimstone stench of a pagan pantheism. The next year, as recipients of the Divinity School Address, they would be opening the windows of their own building to keep from choking. Emerson next considers the second influence on the individual —what he designates as “the mind of the past.” In 1837, books were the basic record of the past, and, at full throttle now, he wastes no time detonating another bomb: “The sacredness which attaches to the act of creation, the act of thought, is transferred to the record. The poet chanting was felt to be a divine man: henceforth the chant is divine also. The writer was a just and wise spirit: henceforward it is settled the book is perfect; as love of the hero corrupts into worship of his statue.” It may be difficult for most of us now to comprehend how truly radical such a pronouncement would have sounded to his listeners, even the less rigid among them. This was, however, long before terms like “active learning” and “critical thinking” gained currency among educators. Lessons at Harvard and other colleges of the day consisted mostly of rote learning and recitation, and classical texts, whether Homer or Shakespeare, were worshipped and seen as models primarily for emulation, not for skeptical scrutiny. He radically insists that one must do “creative reading,” that the proper end of books is “to inspire.” He stresses that the reader must draw from a text only that portion which still seems vital while discarding that which is dead. We can once more imagine that most of the Harvard faculty would not only have shifted restlessly, but would have been aghast at this challenge to their pedagogical methodology and their inviolable 6 texts, whether of the secular or by Emerson’s clear implication, the religious kind. Whatever the reaction, Emerson moves directly into the next influence which must be part of the scholar’s apprenticeship—the world surrounding him. The scholar, he argues, must act in this world, must enter the public forum, not only to be influenced by it but, in turn, to act upon it . “A great soul,” he says, “will be strong to live, as well as strong to think.” However, entering this public sphere, Emerson acknowledges, takes courage. To find this requisite courage, he implores the scholar to cultivate “self-trust,” which we can take to mean selfconfidence. Emerson, later, in a famous essay will substitute the more emphatic self-reliance for self-trust. Revealingly, he devotes the last part of his address to discussing the arduous struggle involved in coming to confidence in oneself, revealingly because the self he is talking about is indisputably his own. Few readers, surprisingly, have noticed that this last part of Emerson’s address takes up more than a third of its total length. Although the content of this section is not nakedly confessional (its author had far too much New England reserve for that) it is obliquely self-referential. One such passage finds the veil tantalizingly dropped, when Emerson says that the aspiring scholar, instead of “treading the old road, accepting the fashions, the education, the religion of society… takes the cross of making his own, and, of course, the self-accusation, the faint heart, the frequent uncertainty and loss of time, which are the nettles and tangling vines in the way of the self-relying and selfdirected; and the state of virtual hostility in which he seems to stand to society, and especially to educated society.” This list of the ills, the false starts, the obstacles, both internal and external, confronting 7 the striving scholar can be seen as Emerson’s reflection on his own circuitous path to confidence and sense of life mission. Now 34 years old, he is surely remembering a stream of earlier set backs, waverings, failures, and even tragedy. He had graduated thirtieth in his class of fifty-nine students, and by his own admission had been only narrowly “approbated” or approved for the Unitarian ministry by the Divinity School faculty. He had lost two brothers (Edward and Charles) to tuberculosis. Most shattering of all was the death of his young bride, Ellen, the love of his life, in early February of 1831, also from tuberculosis. His grief was so deep that he records, in his diary, visiting her grave some time afterwards where, he adds, he gazed upon her face. One recent writer speculates that Emerson might here have been speaking literally, not figuratively. Within a year he resigned the pulpit at Boston’s Second Church, because, he officially announced, conscience kept him from any longer administering the sacrament of Communion. Most probably, he had a deeper motivation, the need to find escape and balm for has grief-stricken heart. At the end of 1832 he embarked for Europe and England, describing this removal as “carrying ruins to ruins.” Returning near the end of 1833, his burden seemingly lightened, Emerson almost immediately began lecturing around the Boston area, essentially field testing views that would soon come into clearer configuration, first in the 1836 Nature essay and even more succinctly in the AS. But I would strongly contend that it is this Phi Beta Kappa address that stands truly as Emerson’s Transcendentalist coming out party. His Nature piece of the previous year was unsigned, and the lectures he had given up to this time were still very much in the rough draft category. Most of all, the Harvard setting, with 8 its notable annual rite and its distinguished gallery of public figures, was the biggest stage he could have hoped for to propel wide debate and accompanying recognition. He made the most of the chance. It was “chance” in another sense. Emerson was a stand-in for a previously invited speaker, who had declined the honor only a few days earlier.