UNIV 112 EAP

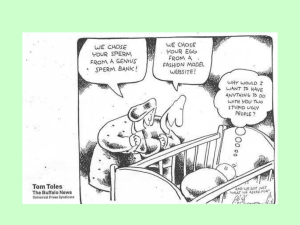

advertisement

Ko 1 Emily Ko Professor Jason Coats UNIV 112: Focused Inquiry March 21, 2015 Parental autonomy and sex determination In today's age of science and technology, it seems we have a plethora of technological advances at our fingertips. As Nicholas Carr, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, points out the omniscient Internet that promotes "'efficiency' and 'immediacy' above all else" (Carr 102), we can begin to see aspects of our lives that reflect the internet's immediacy. For instance, when we see an item we like on Amazon, we order it, ship it, and receive the package in the mail shortly after. This immediacy is also evident in a new technology that is expected to increase in popularity in the near future: genetic engineering for sex selection. Genetic engineering displays a similar "wishlist" and "ordering" system that we see on a site like Amazon; this new technological advance called preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) allows parents to choose exactly which gender their child will be. In part because of the difficulty in reaching a conclusion on the humanity of an embryo, the process of PGD seems unethical as parents in this scenario 'play God' and practice complete parental autonomy. PGD, which can be 100% effective, was first developed for parents likely to pass on serious genetic disorders to their children but has since been noted for its effective sex selection. Very briefly, the process of PGD begins with the woman who takes Ko 2 gonadotropins, a medicine that helps her "superovulate," or produce many eggs. These eggs are collected after they have matured, then fertilized in vetro, and biopsied several days later to determine the sex and presence of genetic diseases. The desired embryo is transferred into the mother's uterus, and the unwanted embryos are usually discarded. (Liao 116-118) Many parents are attracted to exercising their parental autonomy in sex selection as well as to ensure genetic diseases are not passed on to their children. Parents are specifically attracted to PGD because after choosing the desired embryo, there is a 100% certainty that their child will be the correct sex. However, discarding the embryos are seen as harmful to children (especially if one sees embryos as the start of human life), and there may be cultural biases that cause the male gender to be favored. This favoring of male offspring contributes to the bias that PGD seems harmful to women and may even contribute to population growth deficiencies and issues in later generations (Liao 116-118). The underlying ethical issue in the discussion of PGD considers the embryo itself and is similar to the arguments about abortion - perhaps a discussion too deep to completely delve into for the sake of showing that PGD is unethical. The dividing point in deciding whether or not an embryo counts as a 'human being' lays almost entirely on where we may consider the beginning of life, or "personhood." Jeremy Rifkin, a leading liberal social theorist and author of The Empathic Civilization, claims that we should practice empathy and compassion for every human being as well as every other creature on this planet (Asma 13). If we must hold some kind of moral obligation towards other creatures (of different species), we must also show the same compassion and empathy for a human embryo – especially one that may become the offspring of the parents Ko 3 (following the PGD process). Those who support PGD as a moral method of sex selection may focus on the consent given by the parent for the child during many points of childhood and apply this logic to the embryo, since the embryo itself cannot voice an opinion or offer thoughts on its future. However, the embryo in question will one day become an autonomous adult who may give his or her own consent. James and Stuart Rachels, American philosophers of the late 1900s, ties our modern technology with determinism, a sort of faith that everything and every being in the universe happens as a part of the cycle of nature (287). We must, therefore, respect the mere event of a human embryo forming. The consent not given by the human embryo also points to the limits of parental autonomy as they 'play God' by "interfering with the natural processes of reproduction (Liao 116-118). It is indisputable that parents control various aspects of a child's life (what the child wears, activities the child is involved in, etc.); however, parents do not possess a total power over the child's social identity. When approaching non-health related decisions (such as sex determination), we must consider those decisions that are reversible and those that are irreversible. The dress, activities, and habits that parents impose on their children are reversible in adulthood, and the child may choose alternatives, showing us that the lifestyle decisions made by parents do not deprive children of autonomy. Sex change, on the other hand, is completely irreversible, and children have no ability, for the rest of their lives, to alter their sex (with the exception of very few cases of surgical sex change during adulthood). The consequences of irreversible non-health related decisions thus indicate that we may belong to the "great deterministic system" that Rachels and Rachels refer to in assessing technology (287). Ko 4 As previously discussed, the very last step in the PGD process is to discard the embryos not wanted by the parents - those that are not the desired sex or those that may have genetic disorders. However, Peter Singer, a utilitarian philosopher and author of The Expanding Circle, writes "that from an ethical point of view I am just one person among the many in my society, and my interests are no more important, from the point of view of the whole" (Asma 12). What right, then, do parents have in deciding which embryos they will keep and which ones they will throw out according to their own interests and wishes? In his article "The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle," Singer also notes that, with the rise of technology, "we are living in an era of global responsibility" and this global responsibility begins in our homes, where we "could be confident that [our] charity would make any difference." We must, therefore, consider those discarded, undesirable embryos, especially as the embryos are those stemming directly from the parents undergoing PGD. Avoiding genetic disorders may be a legitimate concern of some parents, but those embryos that contain said genetic disorders need to be shown compassion and empathy just as Rifkin points out our moral obligation to show empathy for other creatures as well. This very same logic (on genetic disorders) may be applied, if not more, to the determination of the gender of an offspring, for can a discarded embryo sincerely be at its own fault for being a certain gender that the parents do not desire? In 1999, the Constitutional Court of Columbia made a 'historic decision' that prohibited doctors (and parents) from authorizing and performing surgery on intersexed children, those who were born with both female and male genitalia (Greenberg and Chase). The highest court in Columbia reasoned that the decision of sex change should Ko 5 be left solely on the child when he or she is old enough to make that decision. In other words, parents must look out for their children's best interests instead of pursuing a path like surgery in order to handle their (the parents') own insecurities about the sex of their child. The process of PGD raises the very same issues as performing surgery on intersexed children - parents view one gender as more desirable than the other and pursue their own interests over whatever may occur by chance, or whichever event is 'determined' by the cycle of life and nature (Rachels and Rachels 287). Advocates of PGD may argue that the same logic applied to surgery performed on intersexed children cannot be applied to PGD, however, because the method of PGD allows for sex selection to occur after the sex of the embryo is determined - individual embryos are not specifically modified as other methods of genetic engineering may display. However, the parents choose one of the embryos out of a group of 'suitable' ones to be transplanted into the mother's uterus. The parents thus play a hand in Rachel and Rachel's idea of determinism; in other words, the parents are still 'playing God.' It is unethical, therefore, for parents to micro-plan the sex of their child while discarding the unwanted embryos. Perhaps there would be more moral backing to the PGD process if the leftover embryos were not discarded and were instead given to other parents who hope to have a child. Even then, complete parental autonomy is neither an acceptable nor a sustainable presence in a child's life and determination of sex. Ko 6 Works Cited Asma, Stephen T. “The Myth of Universal Love” Evolving Ideas: 2014-2015 Edition. Plymouth: Hayden-McNeil, 2014. 12-15. Print. Carr, Nicholas. “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” Evolving Ideas: 2014-2015 Edition. Plymouth: Hayden-McNeil, 2014. 101-107. Print. Greenberg, Julie, and Cheryl Chase. "Columbia's Highest Court Restricts Surgery on Intersex Children." Intersex Society of North America. 1 Jan. 1999. Web. 1 Jan. 2015. <http://www.isna.org/node/21>. Liao, S Matthew. “The ethics of using genetic engineering for sex selection.” Journal of Medical Ethics 32.2 (2005): 116-118. Web. 20 Mar. 2015. <http://jme.bmj.com/content/31/2/116.full>. Singer, Peter. "The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle." New Internationalist Magazine 1 Jan. 1997. Web. 22 Mar. 2015. <http://www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/199704-.htm>. Rachels, James and Rachels, Stuart. “The Case Against Free Will” Evolving Ideas: 20142015 Edition. Plymouth: Hayden-McNeil, 2014. 285-297. Print.