Eating Disorder Behavioral Intervention for First-Time Mothers

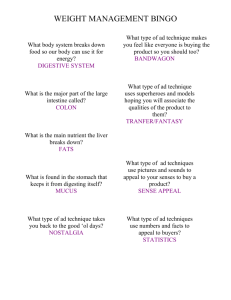

advertisement

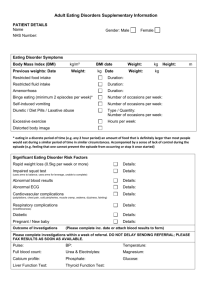

Behavioral Intervention for Mothers with Eating Disorders 1 Eating Disorder Behavioral Intervention for First-Time Mothers Overview This overview provides information regarding mothers with eating disorders and their common behavior towards their children. Reputable sources show a high correlation between certain behaviors exhibited by mothers with eating disorders towards their children. Studies reported from 2002 until 2005 show a consistent pattern of mothers behaving negatively towards their children when they are diagnosed with an eating disorder. Trials from studies show that mothers are less likely to breast feed their children, more likely to engage in negative talk at mealtimes, punish their children when it comes to food and are more likely to feed their children irregularly. Citation: Coulthard, H., Blissett, J., Harris, G. (2003). The Relationship between parental eating problems and children’s feeding behavior: A selective review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders 5 (2), pp 103-115. Objective Design Primary Objective: To determine the short and long-term effects of a behavioral intervention for first-time mothers with eating disorders who have a daughter three years of age or younger. A randomized, pretest-posttest nonequivalent groups design was conducted for two months during the study and for ten years following completion of the study. Women who met study requirements were divided randomly into an experimental (those receiving behavioral intervention) and control group. Treatments Prior to the duration of the study there were random sampling methods to determine participants. Women who were diagnosed with an eating disorder and had a daughter aged three or younger were considered for the study. The control group consisted of women who fit the criteria for the study but were not selected during random sampling. The intervention included behavioral modification for the experimental group, including: Breast feeding for six months Positive conversation at mealtimes Regular mealtimes Avoid using food as a rewards/punishment system Eating with children Some flexibility was allowed as participants adjusted to the changes in behavior during the intervention. Follow-up visit occurred every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the second and third years, and every year for the remaining seven years. In-clinic visits were mandatory and interviews, evaluations and discussion with both mother and daughter were required. Trial Design 854,688 Women Screened 44,231 Women Randomized 22,118 Behavioral Intervention 22,113 Control Behavioral Intervention for Mothers with Eating Disorders 2 Population Female woman with eating disorders Eligibility Criteria for study participation: Woman aged 20 to 35 at the time of study First-time mothers with a single daughter aged three years or younger At least a high school degree Must be a United State citizen Women with eating disorders, defined by: o Currently undergoing treatment at a hospital or clinic after being diagnosed o Treatment must not have exceeded three consecutive months in hospital or clinic o Had a pattern of disordered eating for at least five years prior to and during participation of study Written informed Consent Exclusion Criteria: Those who did not meet study requirements Those who have a history of an eating disorder but have recovered since diagnosis Admitted to a hospital or clinic for more than three consecutive months Those not selected by systematic random sampling during study participation selection (random sampling) Endpoints Primary Endpoint: Mothers who participated in the study created a more wholesome environment for their daughter, including: o positive communication o better social skills at mealtimes o regular eating patterns o eating with children o developing normal eating behaviors instead of using food as a rewards/punishment system Results Primary Endpoint: Early detections in behavioral modification did not go unnoticed, but it wasn’t until later in the study that true effects could be seen. The combination of different treatments led to a successful change in behaviour exhibited by mothers who previously had eating disorders. In addition to radically changing the effect they had on their young daughter, they also benefited from the intervention by overall decreasing their own eating disorders. This created happier and more motivated mothers, both at the end of the study and throughout the ten years of follow-up. Secondary Endpoints: Mothers who excelled at behavioral modification provided a healthier atmosphere for their daughter; however, some participants exhibited frustration and a more stressful environment due to the difficulty of changing their disordered eating behaviors so drastically. Throughout the study some mothers never overcame their frustration, but they did level out over the course of follow-up and fell in with the rest of the statistically significant study population. The independent t-tests in Table 1 suggest that the groups are not statistically different from zero at pretest t(49) = .55, p = .85 (two-tailed). However, independent samples t-test are significantly different at post-test t(49) = 3.24, p = .01 (two tailed). Finally, paired t-tests suggest that behavioural modification symptoms significantly increased in the experimental group, but the control group remained the same. Comparison Secondary Endpoints: Daughters grow up with a more positive selfesteem Daughters grow up with a better body-image Daughters have a lower risk of developing t df p Behavioral Intervention for Mothers with Eating Disorders Paired t-test for Behavioral Modification with Mothers who have Eating Disorders 3 Table 1 80 75 70 65 60 C o mp ar iso n 55 Pr o g r am 50 45 40 35 30 Pr et est Po st t est Independent Samples T-Test Pretest Posttest 0.55 3.24 49 49 .85 0.01 Paired t-tests Control Program 0.25 3.33 49 49 .95 .01 Authors Conclusions The overall benefits of the behavioral intervention outweighed monitoring the control group who received no treatment At the end of the study, the intervention proved beneficial to eating disordered mothers participating as volunteers willing to change their behavior Behavioral interventions should be implemented when woman diagnosed with eating disorders have children, especially a daughter Interventions should be monitored due to adverse affects that may occur as mothers undergo behavior changes, including frustration and difficulty overcoming the harms from the eating disorder Take–Away Message Women with eating disorders treated with behavioral therapy including positive talk at mealtimes, regular eating intervals, breast feeding for six months, and developing normal eating habits demonstrated: Decrease risk of daughter developing eating disorder More positive conversation between mother and daughter Increase level of communication and trust between mother and daughter Higher risk of healthier and normal eating patterns in both mother and daughter The behavioral intervention for mothers with eating disorders has greatly influenced the relationship between mother and daughter and created a healthier environment for both parties. Additionally, daughter has the opportunity to develop normal eating behaviors due to the good influence that mother is providing.