CIVIC LESSONS (NFH 1996)

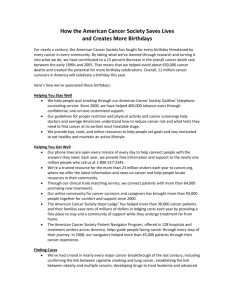

advertisement