Darwall on Action and the Idea of a Second Personal Reason

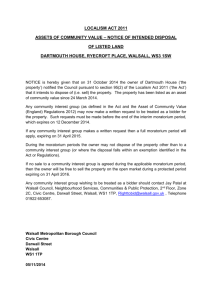

advertisement