Tapping the Power of the Placebo

advertisement

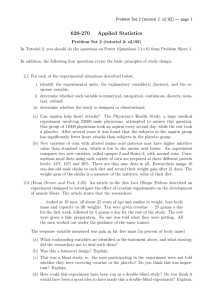

Tapping the Power of the Placebo by Howard Brody, M.D., Ph. D. From Newsweek, August 6, 2000 Sugar pills are potent medicine when taken in the right spirit. Can we put them to practical use? 1. It looked like a medical miracle, and in a sense it was one. Before undergoing experimental brain surgery for her advanced Parkinson’s disease, the patient was so stiff she could barely take a step. A month or two later a TV news magazine filmed the same woman striding easily across the room. The miraculous part is that her operation was a sham. As part of a study of fetal-cell transplantation, researchers had placed her under anesthesia and drilled holes in her skull – but they hadn’t placed any new cells in her brain. Her dramatic improvement was due entirely to the placebo response. The study concluded, in fact, that patients receiving the sham procedure benefited almost as much as those who had live fetal cells implanted in their brains. 2. For decades, the placebo response has been dismissed as the last resort of quack doctors who had no real treatments to offer, and the fantasy improvement of gullible patients with imaginary illnesses. But the placebo response is finally coming into its own as the subject of serious scientific study. In one recent experiment, kids given a vanilla scent with their asthma medicine eventually started responding to the vanilla scent alone. Clearly the mind can heal the body when bolstered by hope and expectation. The question is whether we can consciously exploit the power of placebos. I believe that we can. 3. Researchers have identified several of the pathways linking mental states to physical health. We know, for example, that calming thoughts slow the production of harmful stress hormones. Mental states can also modulate the immune system and trigger the release of internal painkillers known as endorphins. Physicians may someday manipulate these systems mechanically, by stimulating the nerves that control them. But until then, sugar pills and sham surgeries are not the only tools at our disposal. Virtually anything that sends a patient one of four messages – someone is listening to me; other people care about me; my symptoms are explainable; my symptoms are controllable – can bring measurable improvements in health. In one study, Canadian researchers followed people who had recently approached their family physicians about headaches. The patients who said their doctors had listened closely to them also reported getting more relief, and the difference was still measurable a year after the visit. 4. Just as good physicians send these healing messages to their patients during every office visit, we can learn strategies to send them to ourselves. One strategy is to examine the stories we tell ourselves (and others) about our illness. Stories are powerful tools, for when we create a narrative about something, we feel we have explained it. In states of sickness, we tend to focus on what might go wrong and how little we can do for ourselves. Such stories can actually worsen the illness, by fostering feelings of dread and helplessness. But they’re not the only scenarios we can construct. I once had a patient who suffered from severe frequent migraines. He was between jobs at the time, and had begun to fear that his headaches had made him unemployable. When he looked closely at his “headache story,” he found that he was making the migraines worse. At the first twinge of pain, he was constructing a panicky theory about how he would soon be totally incapacitated. Once he had learned to reassure himself that he could handle his migraines, they became less debilitating. He soon started a new job, and after a year at work he had lost only one day of work to his headaches. 5. Tapping the placebo effect is not always as easy as talking to yourself. Sometimes the best strategy is to join a patient support group, where you can share your story and learn from those of people in the same predicament. In a now classic study conducted at Stanford during the 1980s, psychiatrist David Spiegel showed that breast-cancer patients assigned to a support group lived an average of 18 months longer than those receiving standard care, even though their breast cancer had metastasized before the study began. If we look at the group’s activities – members listened to each other, cared for each other, and worked together to understand and manage their symptoms – its success is not surprising. These activities send the very messages that engender the placebo effect. 6. Whether you join a support group or not, you can get more out of medical treatment by pursuing a sense of control. More than 20 years ago researchers taught a group of nursing-home residents how to make more choices in their daily lives. For the next year those who received the control training enjoyed better health, and lower mortality, than residents who didn’t get the training. In another study, researchers taught patients with various chronic illnesses how to be more assertive in their dealings with physicians. In one center after another, groups of “in-charge” patients showed less disability than their untrained peers. Anyone can apply these strategies to achieve better health. That’s why sugar pills are such powerful medicine. The power lies not in the pills, but in ourselves. Brody teaches family practice and medical ethics at Michigan State University. His book “The Placebo Response: How You Can Release your Body’s Inner Pharmacy for Better Health” was recently published by HarperCollins.