Microsoft word version - The University of Tulsa

advertisement

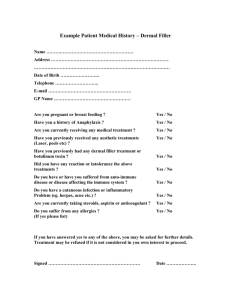

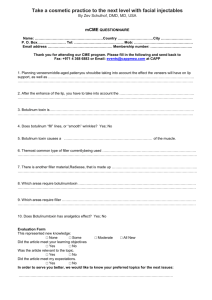

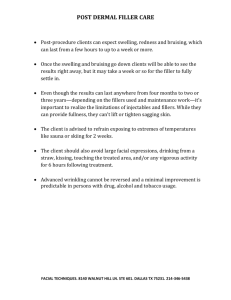

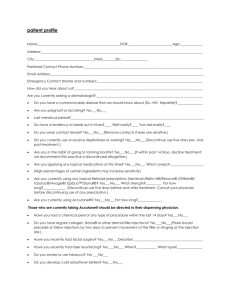

THE UNIVERSITY OF TULSA DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING MECHANICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF POLYMERIC MICROSPHERES TO TRADITIONALLY FILLED VINYL-ESTER EPOXY RESIN by Steven Taylor THE UNIVERSITY OF TULSA May 1, 2006 Taylor, S. ABSTRACT Polymeric microspheres in various weight percents were used as lightweight filler in a vinyl-ester sheet molding compound (SMC) resin system used in the automotive industry for structural components. The results of the microspheres were compared to vinyl-ester resin containing calcium carbonate that is widely used as a low cost filler. Test plaques were molded and formed into samples to determine tensile properties, flexural properties, density, thermal expansion along with evaluating the microstructure and fracture surfaces of the composite. It was found that the fillers used can be characterized as small voids in the resin decreasing the overall tensile strength of the composite. In addition, Paul’s theoretical model best predicts the modulus of each composite. INTRODUCTION Polymeric microspheres can be used as a light weight alternative to traditionally used calcium carbonate as the filler material in SMC. The concept of using hollow microspheres as filler material comes from the late 1970's when these micro spheres were used in combination with a resin system for lightweight plastics in marine applications. As the automotive industry looks for stronger, lighter and inexpensive alternatives to sheet metal, hollow microspheres are becoming readily available and can provide the potential weight saving required. With a lower bound density of 0.10 g/cm3, microspheres can lower the standard density of SMC parts from 1.5 g/cm3 to 1.3 g/cm3 or lower. Currently, microspheres are being used in a wide variety of applications, which include bowling balls and sport and leisure boats. General Motors is presently the only known automobile manufacturer using microspheres in production on their Chevrolet Corvette. Ford Motor Company has the goal of producing low density structural SMC components within the next year and components with class-A surfaces following shortly. Although the price for microspheres is currently around $7.00 / lb, prices are expected to drop with an increase in demand and the availability of more efficient production processes. Potential advantages include lighter parts with as good or better material properties than those currently in production. RELEVANT RESEARCH Tension, compression, flexural and fracture test were conducted on composites containing various volume fractions of 3M glass bubbles K 15 and K46 and Phenoset BJO-093 as filler in an Epicote 1006 epoxy resin system was investigated by Wouterson et al. Mechanical test data were normalized and presented as specific mechanical and fracture properties. Both tensile and flexural test revealed similar results in modulus, strength and failure modes. 3M K15 glass microspheres had the largest thickness to radius ratio and showed an increase in specific modulus with increase in volume fraction of filler. The 3M K46 glass microspheres showed a constant specific modulus with increase in volume fraction of microspheres, and a decreasing trend was found in specific modulus of phenolic microspheres. An increase in tensile strength for all fillers was found between 0% and 20% volume fractions. Volume fractions of 30% and greater showed a decreasing trend in tensile strength. A Decrease in Flexural strength was found with an increase in volume percent of filler for all three fillers. Scanning electron Page 1 Taylor, S. microscope images of fracture surfaces from the different mechanical tests show plastic deformation of the epoxy and debonding of microspheres from the resin. The debonding of microspheres was found to cause a reduction in matrix volume resulting in lowered material strength. Dikie reported findings of effective modulus of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) filled with various volume fractions of glass beads and dispersed rubber phase. The modulus of the material was experimentally found using dog-boned shaped tensile specimens. The multi-component form of the Kerner model for modulus of the composite was found to be an inappropriate fit through the data. The report concludes the predicted modulus may be dependent on other factors not included in the Kerner model including size distribution, filler particle deformability and filler to matrix modulus ratios. Li et al. investigated several models to predict the modulus of asphalt concrete consisting of a binder and aggregate. The modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and volume fractions for both the aggregate and binder were all known and assumed to be isotropic. Resilient modulus test were conducted per ASTM 4123-82. Known raw material properties for each phase of the composite were used in theoretical models including rule of mixtures, Hirsh, Hashin composite spheres, and Christensen Lo models. The Hirsh, Hashin, and Christensen Lo models gave reasonable predictions, but differences could be attributed to the high volume fraction of large sized aggregate and the bond and interaction between the different phases of the matrix. Hseih et al. conducted a study comparing 12 different theoretical models to the experimental results of the elastic modulus of a two phase material comprised of aluminum oxide containing 0 to 100% volume percentage of nickel aluminide. The samples were made using a hot-pressing technique then determining the modulus using an ultrasonic method. Hsieh showed the Reuss and the Hashin-Shtrikman lower bond equations gave good modulus predications to the experimental data. The objective of the research described in this report is to determine the effective modulus of filler used in vinyl-ester sheet molding compound resin. In particular, several theoretical models will be compared to a vinyl-ester base resin containing various volume fractions ranging from 0 – 50% of calcium carbonate, both with published mechanical properties. Those theoretical models that best predict the modulus of the control will then be used to determine the effective modulus of the polymeric microspheres. In addition, the effects on other material properties as a function of filler type and filler volume, such as percent shrinkage, flexural strength, coefficient of linear thermal expansion, and density will be evaluated. EXPERIMENTAL Materials The materials used for this study include the dispersion of polymeric microspheres and calcium carbonate as fillers in a vinyl-ester resin. The microspheres were Dualite E130-055D which consists of a polyvinylidene chloride copolymer shell coated with calcium carbonate. The average nominal density of the spheres is 0.130 g/cm3 with an average particle size between 45 – 65 μm. The microspheres strength is characterized by their ability to withstand pressure commonly referred to as burst Page 2 Taylor, S. strength. Because of the polymeric nature of the spheres, the spheres burst strength is both time and temperature dependent. Calcium carbonate is widely used as low cost filler in a variety of resin systems. Calcium carbonate came from Korth Kristalle GMBH in a powder form with an average particle size on the order of 10 μm. The fillers were mixed with Ashland Arotech Q6055 vinyl-ester resin containing appropriate amounts Luperox DDM-9 as a catalyst, and Westdry Cobalt 6% and Aldrich N, N-Dimethylaniline as accelerators. A fixed two minute gel time at 90°C established the appropriate ratio of resin to catalyst and accelerators. Sample Preparation Each filler was mixed with the vinyl-ester resin system in volume percents ranging form 0 to 50% in 10% increments. The contents were stirred slowly to prevent the formation of air bubbles and to properly distribute the filler throughout the resin. The mixtures were injection molded into plaques measuring 150mm by 80mm by 3.5mm at 90°C and 275 kPa and allowed 10 minutes to cure. After removal from the mold, the plaques were subjected to a post cure at 100°C for 60 minutes and stored at standard atmospheric conditions. Each plaque’s width was measured in five places and compared to the 80mm width of the mold surface to determine the percent shrinkage from the molding process, and then cut into test specimens for mechanical testing. Mechanical Testing Tensile test and immersion density test were performed with each sample. Tensile test specimens were cut into 80mm by 19mm blanks and had a 10mm gage length machined using a high speed router and a tensile specimen jig. Tensile specimens were tested at standard laboratory conditions, at a crosshead speed of 10mm/min on a Measurements Technology Incorporated (MTI) universal load frame. A 2000 kg load cell and MTS 10mm extensometer measured force and strain, which was used to obtain ultimate tensile stress, ultimate tensile strain and Young’s modulus. A total of 8 specimens were tested for each sample per ASTM D638. Specimens measuring 80mm long by 13mm wide were cut from plaques and used for immersion density test. The specimens had cut edges wet sanded with 320 grit sand paper and width variance kept within 0.05mm. Immersion density measurements were made in agreement with ASTM 792-00(3). Test specimens were weighed dry using an A and D Company/Limited electronic balance model number HR-60. Next, the specimens were placed into a 250mL beaker and buoyant forces were measured using a MettlerToledo density determination kit and an A and D Company/Limited electronic balance model number HR-60. Using Archimedes principle and the buoyant force and dry weight of the specimen, the density was calculated. Each sample was comprised of 8 test specimens. Microstructure Analysis Cross sections from each sample of plaques were cold mounted and labeled for convenient handling and referencing when looking at the microstructure under a microscope. Cold mounting procedures require little heat and pressure, which minimizes Page 3 Taylor, S. degradation to the polymer samples. Plastic forms were used to mold a two part polyester resin and hardener around the test specimen. Cross sections measuring approximately 25 mm by 10 mm by 3 mm were cut from the center section of test plaques and placed upright inside the plastic form. The two part polyester resin system was mixed and poured into the plastic ring and allowed to cure overnight. After the polyester was cured the specimens were polished smooth for viewing using a Nikon metallograph microscope at a magnification of 20X. Image J image processing and analysis software was used to evaluate filler percentage of the microstructure. Fracture Surface Analysis Fracture surfaces from the tensile test specimens were prepared for viewing with a scanning electron microscope (SEM). First, the fracture surface was removed from the test specimen to allow insertion into the SEM viewing chamber. Next, aluminum tape was used to adhere the fracture surface to a graphite disk. Due to the lack of electrical conductivity of the composite, the sample was placed in a sputter coater supplied with a gold target. The sample was sputter coated for approximately 5 minutes, receiving an approximate 30 micron thick surface layer of gold. Lastly, the specimen was placed into a vacuum chamber before being placed on the stage of the scanning electron microscope for fracture surface analysis. THEORETICAL MODELING Numerous theoretical models have been proposed for predicting the properties of a material such as density, modulus and tensile strength. Among the most common of these models is the Rule of Mixtures parallel and series model. The parallel model, often referred to as iso-strain, states that regardless of the load, both the filler and resin will have equal amounts of strain (Figure 1). Base Resin Filler Base Resin Figure 1: Parallel (Iso-strain) Model The parallel model is a function of volume percent of base resin and filler denoted by Vr and Vf , respectively, and the material property of interest for each the base resin and filler, in this case Young’s modulus Er and Ef, respectively. Equation 1 gives the relationship of the predicated composite modulus (Ec) as a function of the individual phase characteristics. E c E r Vr E f V f (1) Page 4 Taylor, S. The series model, also referred to as the Iso-stress model, states that each phase of the composite carries the same amount of stress, but is allowed to have different values of strain. Using the same nomenclature as Equation 1, the series model is illustrated in Figure 2 and the mathematical relationship given in Equation 2. Base Resin Filler Base Resin Figure 2: Series (Iso-stress) Model Vf V 1 r Ec Er E f (2) The rule of mixtures gives an upper bound (parallel model) and lower bound (series model) prediction for two-phase materials. Most other theoretical models give a prediction in between the two rules of mixtures. This investigation looked at a number of models and found three that give comparable predictions to the experimental vinyl-ester sheet molding compound – calcium carbonate modulus data. These models include Hashin-Shtrikman model (Equation 3), Kerner model (Equation 4), and the Paul model (Equation 5). Kc Kr Kc Vf 31 V f 1 K f K r 3K r 4G r (3) K r 3K f 4 K r 4GrV f K f K r 3K f (4) 1 V (5) Er Er E f Er V f 2 Ec 4Gr 3V f K r K f E r E f E r V f 2 2/3 2/3 1/ 3 f These equations use the same nomenclature as that in the rule of mixtures where V is volume fraction, E is Young’s Modulus, K is bulk modulus and G is shear modulus. Subscripts c, f, and r denote the composite, filler, and resin, respectively. Page 5 Taylor, S. RESULTS AND DISSCUSSION Percent Shrinkage When components of a subassembly are made from a molding process, it is important to be able to predict how the component will shrink to create a part that is within design specification. Figure 3 shows the percent shrinkage of molded plaques containing calcium carbonate and polymeric microspheres as filler. 5.0% Percent Shrinkage 4.0% 3.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.0% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Filler Volume Percentage Figure 3: Percent Shrinkage versus Filler Volume for (♦) CaCO3, (■) Polymeric Microspheres, (▲) Neat Vinyl-Ester Resin and (--) Suggested Trend Lines. Table 1: Percent Shrinkage Statistical Data Material No Filler 10% CaCO3 20% CaCO3 30% CaCO3 40% CaCO3 50% CaCO3 10% E130-055D 20% E130-055D 30% E130-055D 40% E130-055D 50% E130-055D Averagae 0.031 0.023 0.023 0.026 0.019 0.013 0.026 0.033 0.036 0.032 0.033 Stdev 0.012 0.011 0.007 0.001 0.005 0.004 0.011 0.010 0.004 0.007 0.001 COV 0.383 0.489 0.289 0.054 0.287 0.329 0.435 0.310 0.100 0.209 0.033 From Figure 3 and Table 1, it is noticed that there is much scatter for all volume fractions of calcium carbonate and polymeric microspheres. Although a decrease in average percent shrinkage can be seen with an increase in volume percentage of calcium Page 6 Taylor, S. carbonate a trend between percent shrinkage, volume fraction of filler and filler type is statistically insignificant. All the data do have distinctive upper limits in the scatter as shown with the suggested trend lines. This indicates that the total percent shrinkage may not be captured by width measurements taken. The plaques do contain two additional dimension, length and thickness that were not measured, and percent shrinkage could possibly be an anisotropic characteristic of the material that is dependent on molding processes. Immersion Density Immersion density tests reveal two key pieces of information, the obvious being the weight of the material, and the other is a macro-level indication of how well spheres are distributed compared to theoretical calculations. The densities of both fillers and the resin system are all known and have been provided by the suppliers. The rule of mixtures parallel model was used to create the theoretical curve fits though the data (Figure 4). 2.5 Density (g/cm3) 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Filler Volume Percentage (%) Figure 4: Density versus Filler Volume for (♦) CaCO3, (■) Polymeric Microspheres, (▲) Neat Vinyl-Ester Resin and (─) rule of mixture’s curve fit. There tends to be good correlation between the theoretical and actual values for all volume percentages of calcium carbonate ranging from 1.55% difference at 10% calcium carbonate by volume to 3.55% difference at 50% calcium carbonate by volume. The polymeric microspheres have a downward trend, but have linear increase in percent difference with increase in filler volume percentage. At 50% microspheres by volume there is 51% difference between the theoretical value and actual data. Microstructure Page 7 Taylor, S. analysis samples were prepared to determine the micro-distribution of the spheres. These results along with the density data will provide further insight into the differences between the modeled and actual data, and are discussed in a following section. Tensile Test Figure 5 shows modulus versus volume percent of calcium carbonate. It is seen that the parallel and series models give the upper and lower bounds with the remaining three models falling in between. Table 2 shows the percent difference between theoretical models and experimental data. The Paul model gives moduli predictions more accurate to experimental values at larger values of filler volumes with a 3.7% difference at 50% filler, but has difference of over 15% at lower volume fractions. The Kerner model has a difference of less than 10% for all cases, and therefore can be considered the best model for the vinyl-ester / calcium-carbonate material. 14000 Parallel 12000 Paul Modulus (MPa) 10000 Kerner 8000 Hashin-Shtrikman 6000 4000 Series 2000 0 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Volume Percentage of Filler (%) Figure 5: Young’s Modulus versus Filler Volume of (♦) CaCO3 and (▲) Neat Vinyl-Ester Resin. Table 2: Percent Difference of Theoretical Models from Figure 5 % Filler 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Actual E 3269 4608 5617 7276 9468 12282 Parallel 0.01% 137.47% 231.42% 261.34% 258.71% 239.01% Series 0.01% 21.53% 27.99% 36.92% 43.98% 48.86% Hashin 0.01% 11.01% 8.43% 11.04% 13.33% 14.20% Paul 0.01% 15.83% 21.25% 15.60% 8.98% 3.74% Kerner 7.00% 5.00% 2.49% 5.47% 8.08% 9.18% Modulus versus filler volume for the polymeric microspheres is shown in Figure 6, along with the five theoretical models used to predict the calcium carbonate data. Each Page 8 Taylor, S. model was independently fit through the data to determine the effective modulus of the spheres. Table 3 gives the tabulated percent difference between the theoretical models and experimental data for filler volumes ranging from 0% to 50%. 6000 Kerner Modulus (MPa) 5000 4000 Paul 3000 Parallel Series 2000 Hashin-Shtrikman 1000 0 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Volume Percentage of Filler (%) Figure 6: Filler Volume versus Young’s Modulus of (■) Polymeric Microspheres and (▲) Neat Vinyl-Ester Resin Table 3: Percent Difference of Theoretical Models from Figure 6 % Filler 0 10 20 30 40 50 Actual E 3269 3616 3216 3190 3169 2579 Parallel 0.01% 10.33% 0.01% 0.01% 0.18% 21.64% Series 0.01% 10.34% 0.02% 0.02% 0.17% 21.69% Hashin 0.01% 10.00% 0.23% 0.34% 1.42% 18.62% Paul 0.01% 10.33% 0.01% 0.04% 0.22% 21.58% Kerner 50.54% 53.24% 92.45% 115.27% 139.08% 222.58% Table 4: Theoretical Model’s Effective Modulus Model Parallel Series Hashin Paul Kerner Effective E (Mpa) 3,005 3,018 2,636 3,005 8,590 From Figure 6 and Table 3, the Kerner model giving the best fit for calcium carbonate, had the worst fit for the polymeric microspheres. The Paul model, which gave a slight overestimate of the calcium carbonate data, gives a good prediction for the modulus of the polymeric microspheres. From Table 4 and the percent difference Page 9 Taylor, S. between the experimental data and theoretical models in Table 3, the effective modulus of the polymeric microspheres is 3,000 MPa. Figure 7 shows the average ultimate tensile stress versus volume percentage of filler for test specimens containing calcium carbonate and polymeric microspheres. Ultimate tensile stress decreases with an increase in filler volume percentage for both fillers. A line which is equal to resin volume percentage times the ultimate stress of the neat resin was fit through the data. The line fits the decreasing trend of the data, signifying that the addition of filler creates voids, decreasing the overall ultimate tensile strength of the material. 80.0 Ultimate Tesnile Stress (MPa). 70.0 60.0 50.0 40.0 30.0 20.0 10.0 0.0 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% Volume Percentage of Filler (%) Figure 7: Ultimate Tensile Stress versus Volume Percentage of Filler for (♦) CaCO3 and (■) Polymeric Microspheres. Microstructure Analysis Images of the microstructure with 100μm scale for all volume fractions of both fillers were taken using a Nikon metallograph microscope and are shown in Figure 8. Overall the calcium carbonate samples show a good dispersion of particles and there is good correlation between theoretical and actual volume fractions of calcium carbonate using Image J image processing and analysis software. It appears that there are significantly less microspheres than should be for all volume fractions of polymeric microspheres. At 10% volume fraction of spheres, Image J indicated less than 1% coverage of microspheres over the area of the image. The Microstructure at 50% volume fraction of microspheres had about 21% coverage of microspheres. Page 10 Taylor, S. 10% DL E135-055D 10% CaCO3 20% DL E135-055D 20% CaCO3 30% DL E135-055D 30% CaCO3 40% DL E135-055D 40% CaCO3 50% DL E135-055D 50% CaCO3 Figure 8: Microstructure Analysis Page 11 Taylor, S. There are a number of explanations as to why the actual volume fraction of spheres is low. The first is that polymeric microspheres tend to deform and shrink at high pressures and elevated temperatures as used in the molding process. At 550 KPa and 90°C the supplier says the spheres will have a decrease in size around 30%. The remainder of the shortage of spheres could be one of two things. First, the spheres could have a density greater than specified by the supplier causing the volume fraction of spheres to be lower since the resin and fillers were mixed by appropriate weight. Secondly, the density of the resin is one order of magnitude greater than that of the microspheres causing the spheres and resin to separate before or during the molding process. The spheres were weighed and have a density close to that specified by the supplier. In addition, the vinyl-ester resin / microsphere matrix was mixed less than 60 seconds before each plaque was molded. Further testingt may be needed to fully understand and quantify what is happening to the microspheres during the mixing and molding process. The microstructure images and lack of spheres through the cross section of the samples explain why the density measurements were greater than predicted in the immersion density test. Fracture Surface Analysis Fracture surface images of a tensile specimen containing 40% polymeric microspheres were obtained to understand the mechanics for failure. From Figure 9, it can be seen that the bond between the polymeric microspheres and vinyl-ester resin is poor, causing there to be whole spheres and pits in the surface. Although hard to see, the largest sphere had a separation between the outer layer and resin on the bottom right corner. The 20um sphere in the lower left corner of the image has broken in two, which is what should be expected for the majority of the spheres in this resin / filler system. The image supports the idea of both fillers having the effect of small voids through the cross-section of the material, decreasing ultimate tensile strength. In order to increase the overall strength of the material, filler sizing effects should be investigated to create a stronger bond between resin and filler. Figure 9: 40% Polymeric Microstructure Tensile Surface Fracture Surface Page 12 Taylor, S. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS In this study vinyl-ester plaques containing varying volume percents of calcium carbonate and polymeric microspheres as filler, were compared by percent shrinkage, density, tensile properties and microstructure analysis. Various theoretical models including rule of mixtures, Kerner model, Paul Model and Hashin-Shtrikman Model were all used to predict material behavior. The following conclusions have been made: 1. The Paul theoretical model does best in fitting both the calcium carbonate and polymeric microspheres data for elastic modulus. 2. The effective modulus of the polymeric microspheres in Ashland Q6055 vinylester resin is approximately 3000Mpa 3. Further testing should be performed to fully explain the lower than expected percentage of polymeric microspheres in molded plaques for all volume fractions. 4. Scatter in percent shrinkage measurements may be caused by inadequate measuring techniques. 5. The decrease in ultimate tensile strength with increasing filler amounts is caused by poor adhesion between the resin / filler matrix 6. Sizing effects should be investigated to create a greater bond strength between filler and resin to increase the ultimate tensile strength of the material. Page 13 Taylor, S. REFRENCES 1. Wouterson, E. W., Boey, F. Y.C., Hu, X., Wong, S.C., “Specific Properties and Fracture Toughness of Syntactic Foam: Effect of Foam Microstructures,” Composites Science and Technology, Vol. 65, 2005, pp. 1840-1850. 2. Dickie R. A., “On the Modulus of Three-Component Particulate-Filled Composites,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 17, 1973, pp. 25092517. 3. Li, Yongqi, and Metcalf, John B., “Two-Step Approach to Prediction of Asphalt Concrete Modulus from Two-Phase Micromechanical Models,” Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, July/August 2005, pp. 407-415. 4. Hsieh, Chin-Lung, Tuan, Wei-Hsing, “Elastic Modulus of Two-Phase Materials,” Bulletin of the College of Engineering, N.T.U., Vol. 89, October 2003, pp. 35-44. 5. ASTM D638-03, “Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics,” American Society for Testing and Materials, 2003 6. ASTM D792-00, “Standard Test Method for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Desnity) of Plastics by Displacement,” American Society for Testing and Materials, 2000 7. Mettler-Toledo GmbH, Laboratory and Weighing Technologies, "Operating Instructions, Density Determination Kit," Greifensee, Switzerland, 1998 8. ASTM D6272-02, “Standard Test method for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials by Four Point Bending,” American Society for Testing and Materials, 2002 Page 14