The Legacy of Samuel P. Huntington: His Contributions to

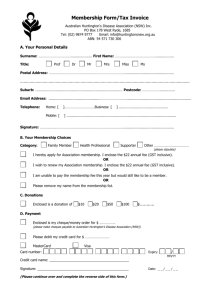

advertisement

209 THE LEGACY OF SAMUEL P. HUNTINGTON: HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO INTERNATIONAL AND AREA STUDIES GORDON L. BOWEN MARY BALDWIN COLLEGE [Editor’s Note: Dr. Bowen, Professor of Political Science and International Relations wrote this appreciation of Samuel P. Huntington (1927-2008) shortly after his death on 24 December 2008] A great man has died and we all are diminished by the loss. Samuel P. Huntington was Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor at Harvard University; and had been chairman of that august university's Academy for International and Area Studies. A graduate of Yale University, he earned an M.A. at the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1951. In an age of specialization and narrow professionalism within higher education, Huntington represented a far older tradition among scholars: committed both to rigorous scholarship within the academy, and to the wider role of "public intellectual" with responsibilities to his community beyond the ivy towers. Huntington contributed richly to nearly all areas of modern American political science. His major works in the field of comparative politics defined the direction of that subfield for a generation. He wrote cogent analyses of democracy and authoritarianism, and contributed major works in the areas of international relations and strategy during a long and successful academic career. In all his works, a sensitivity to historical contexts pointed political scientists toward the importance he found in maintaining dialogue with the evidence of the past. For many years Huntington also advised various agencies of the U.S. government on matters of national security. This keen focus on relevance led Huntington's first major concern as a professor to be on the problem of national economic and political development, especially in the contested regions of the Third World. In the 1950s and 60s, an age of optimism about the natural harmony of economic modernization, social development, and the emergence of political democracy, Huntington was among the first to sound discordant notes. He took the position that economic change inherently was politically destabilizing, and that, therefore, the key to successful modernization lay in establishing institutions that could impose political order. Democratic development, he argued, would not necessarily emerge from change; and change would not necessarily be orderly, or produce outcomes which were in the U.S. interest. In 1957 in his The soldier and the State; the Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations and in the early 1960s, these emphases led him to write about the potentially positive role of military forces in governing (e.g., Changing Patterns of Military Politics, 1962) and most notably to contribute a major work in comparative politics, Political Order in Changing Societies (1968). 210 At this time Huntington acquired considerable notoriety when, in a 1968 article for Foreign Affairs ("The Bases for Accommodation"), he argued that the rural population in Vietnam might usefully be driven from the countryside through "forced draft urbanization" in order for the U.S. successfully to win the Vietnam War. Two years later, Huntington published an edited volume on Authoritarian politics in modern society; the dynamics of established oneparty systems, which emphasized their durability. The emphasis on the need for order reflected Huntington's ill-ease with aspects of his own university environment, where his views had on occasion led to student protests directed against the positions he espoused. With a Japanese academic and a European scholar as co-authors, in 1975 Huntington branched out to critique Western societies' disorderliness in The Crisis of Democracy (1975), a book published by the influential Trilateral Commission, of which he was a member. The co-authors perceived there to be danger to stable democracy in excessive responsiveness to the public. In the 1970s, this tendency was leading developed democratic states toward crisis; and the next year this tendency, again, was the danger that Huntington saw to most menace the Third World (in No Easy Choice : Political Participation in Developing Countries, 1976). Much as he found episodes of flirtation with passionate creeds throughout American history to obstruct realization of our national interests (in The Soldier and the State), so Huntington in the 1970s found the temptations of idealism again unconvincing. But Sam Huntington remained willing to try to influence those who did not fully subscribe to his perspective. Despite his jaundiced attitude toward idealism in politics, Huntington joined perhaps the most idealistic of all U.S. administrations, the Carter Administration, as director of security planning for the National Security Council. Returning to Harvard in the 1980s, Huntington's influence continued to grow. A founding editor of the influential journal Foreign Policy in the 1970s, he also served as President of the American Political Science Association. During the Reagan years Huntington's direct influence at the policymaker level waned, but he continued an active scholarship increasingly focused on the problems of maximizing U.S. interests in foreign affairs, and frequently was invited to join conversations with personnel of government agencies. Among his publications in this era were ones focused on American politics and policy: American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (1981), American military strategy (1986), and the edited volume Reorganizing America's Defense: Leadership in War and Peace (1986). After the end of the Cold War, the further evolution of Huntington's thought helped to shape much of the debate over the nature of the emerging world, and the U.S. role in it. In The third wave : democratization in the late twentieth century (1991) he again weighed in against idealism, attacking the excessive optimism about the universality of democracy which was associated with the "End of History" hypothesis posed first in 1989 by Francis Fukuyama. In a 1993 Foreign Affairs article "The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order," and 211 in the 1996 book of the same title, Huntington saw not a coming age of universal democracy but a new age of conflict, with non-Western civilizations colliding with the West to define the future. Controversy swirled around his "clash" thesis, most provocatively goaded on by one piquant phrasing of Western relations with the world of Islam: "Islam has bloody borders." One barrier to U.S. success in a world of clashing cultures and civilizations, he argued in a 1997 Foreign Affairs article entitled "The Erosion of American National Interests," would lie in the excessive responsiveness of U.S. foreign policy to interest group pressures, especially that of ethnic minorities. These interests, he controversially claimed, often served to advance "nonnational" purposes. Journals as diverse as The Nation and The New Republic found a whiff of WASP elitism in these views. But Huntington's concern with the impact of minorities on the political health of the nation remained, and again it was articulated in a 2004 article in Foreign Policy, "The Hispanic Challenge," an assessment of America's largest minority's that found in Hispanic immigrants' failure to assimilate a problem large enough to menace national "Protestant" culture and national identity. Both Foreign Policy and Foreign Affairs soon published lengthy rejoinders. With these contributions, Huntington re-established for a new generation his lengthy credentials as a premier voice lamenting the decline of WASP culture and influence. Huntington's foci ranged broadly throughout his career. His strongest quality as a writer was as a synthesizer of facts into coherent frameworks that were intelligible to laymen and experts alike, a well suited model to anyone who aspires to occupy the role of public intellectual. His seminal thinking in comparative politics notwithstanding, ultimately his most enduring contributions may prove to have been in the area of national strategy. In no other area did Samuel Huntington made more accessible to broad audiences the realistic assessment of life that is the defining common denominator in all his work. In this regard, his 1999 article "The Lonely Superpower" (Foreign Affairs, March/April) argued against American hubris. In it Huntington suggested that the impression that some Americans pundits (e.g., Charles Krauthammer), and some American scholars (e.g., William Wolforth) have that the world by the 1990's had become "unipolar" --i.e., one in which only the U.S. remains a powerful state capable of imposing its will-- was an illusion, an especially dangerous one since many Bush-era policymakers came to behave as if they believed the illusion to be the true state of the world. In all matters, Samuel Huntington above all was an American citizen, committed to sharing with students and publics his vision of the better course for the nation. Thus, after September 11, 2001, as a rift developed between American intellectuals and their European counterparts concerning the appropriate responses to terrorism, Huntington was among the 212 prominent signatories of a public letter urging Europeans to support the U.S. more fully in its war goals. As the torch of leadership passes to a new generation of American political leaders, the absence of the option of listening to the counsel of Samuel Huntington may weaken us all: Huntington passed into the one unending night ahead of all of us on Christmas Eve, 2008.