POPULATION GROWTH, MILENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS

advertisement

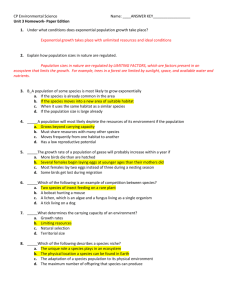

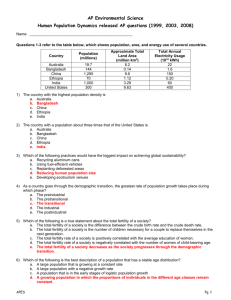

POPULATION GROWTH, MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH Department of Reproductive Health and Research World Health Organization March 2006 Paper submitted to the UK All Party Parliamentary Group on Population, Development and Reproductive Health for the Parliamentary Hearings between May – July 2006 on “Population Growth – Impact on the Millennium Development Goals" 1 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. 2 Introduction The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) aim to promote human development by ensuring improvements in a range of areas including poverty alleviation, education, health and environment (United Nations General Assembly 2000). All eight goals are interlinked and closely related to population issues. Their achievement is largely influenced by changes in population dynamics including population size. This paper explores the potential impact of population growth on human development and therefore, achieving the MDGs in broad terms. In this context, population growth refers to “rapid” population growth defined as 2% or more annual increase in the size of population. The focus is on the trends and consequences of population growth at the societal level and its implications for human development based on theoretical and empirical literature. The role of reproductive health in terms of both the causes and consequences of population growth and the likely impact of reproductive health care on achieving selected goals [goal 3 on women’s empowerment and gender equality; goal 5 on improving maternal health; and the part of goal 6 on combating human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS)1] are discussed. Population growth The rapid population growth from the 1950s until the present during which the world’s population almost tripled to become its current level of 6.5 billions became a concern of the international community from the late 1960s (Raleigh VS 1999; United Nations Population Division 2005). This was centuries after Thomas Robert Malthus wrote his “essay on population” where he discussed the possibility of future “overpopulation” and the negative impact this would have on limited resources, in particular food supplies. Malthus' suggested solution was “to proportion the population to food, since the food could not be proportioned to population” (Malthus TR 1999). Critiques of Malthus have opposed his theory arguing that he failed to foresee the potential technological improvements that would increase food production (Sen A 1994). Indeed, for example in India, empirical evidence showed that the growth rate of grain production between 1951 and 1991 has kept up with population rates and even increased 1 The MDG 6 is to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases. 3 with a small margin (Crook N 1996). However, in the late 1960s, alarmed by the high population growth rates and research reporting substantial economic costs due to continued high fertility, neo-Malthusian voices appeared expressing similar concerns and proposing further policy actions to limit fertility in addition to the provision of family planning alone (Davis K 1967; Ehrlich PR 1968). According to the demographic transition theory, rapid population growth during a certain period of time happens in all societies, because improvements in living conditions and health care lead to reduced death rates first (Raleigh VS 1999). Declines in birth rates (fertility) follow this after a certain lag period as the need for having "extra" children to offset high child mortality decreases. In addition, as societies develop and socioeconomic development takes place, the need for more children as sources of labour and carers of ageing parents becomes less (Kibirige JS 1997). In more developed countries which already have completed their demographic transitions, population sizes are now hardly changing. Developing countries, on the other hand, are at different stages: rapid falls in mortality have been followed by declining birth rates in some developing countries, such as India, Bangladesh and Thailand, but due to the earlier levels of high fertility, their populations will continue growing for some time (Raleigh VS 1999; United Nations Population Division 2005). In contrast, particularly the group of 50 least-developed countries, most of which are located in Africa, are characterized by continuing rapid population growth (United Nations Population Division 2005). Fertility is still high in most of the least-developed countries and, although it is expected to decline, will remain higher than in the rest of the world for the coming decades. It is predicted that the total population of the 50 least-developed countries will more than double, passing from 0.8 billion in 2005 to 1.7 billion in 2050 (United Nations Population Division 2005)2. A possible explanation for the continuing high fertility and delay in completion of demographic transition in certain countries is that the need for large families continues in the context of stalling socio-economic development (Kibirige JS 1997). It can be 2 These estimates take into account the expected mortality due to HIV/AIDS in relevant settings. 4 concluded, therefore, that population growth needs attention in countries that are also a long way off reaching the MDGs (Sahn DE & Stifel DC 2002). World population almost tripled during the last half-a-century Rapid falls in death rates in some developing countries have been followed by declines in birth rates, but due to the earlier levels of high fertility, their populations will continue growing Fertility remains highest in the 50 least developed countries – their demographic transition is delayed by slow economic growth and consequent low levels of investment in human capital development Consequences of population growth Effects on economic growth Although it is clear that populations with higher socio-economic development have lower fertility levels, and thus stable population sizes, the evidence with respect to the effect of population growth on the economic growth and development of populations (and hence the likely impact of population growth on reaching the MDGs) is less straightforward. Studies report conflicting results: either negative (Ahituv A 2001; Kelley AC & Schmidt RM 1995) or positive (Crook N 1996) effects of population growth on economic growth. The direction and size of the effect may vary from country to country according to which stage of the demographic transition the country is at and its related characteristics such as the political and economic context (Barlow R 1994; Kelley AC 1988). For example, an analysis of 45 countries found a greater positive effect of declining fertility on economic growth for poorer countries and those with higher initial fertility levels (Eastwood R & Lipton M 2001). Declining fertility and population growth contribute to development as shown by their positive influence on economic growth Economic growth is mainly driven by accumulation of human capital One recent analysis of 86 countries showed increased economic growth with declining population growth, fertility and mortality. The only growth-inhibiting population trend was the decline in the size of the working-age group, although this was not universal across data sets (Kelley AC & Schmidt RM 2001). It appears that what 5 matters for economic growth is the accumulation of human capital (educated, skilled and healthy population) (Barro RJ 2001; Orbeta AC 1992; Rosenzweig MR 1990; Strulik H 2005). Human capital implications Populations experiencing rapid growth demonstrate particular characteristics in terms of composition. First, they have distinct age structures where approximately 40% of the population is under 15 years of age. In the later stages of demographic transition, the size of the working-age group increases (McNicoll G 1984). Changing age structure has several implications for development of human capital at the population level. More infrastructure and investment are needed for schooling needs of the increasing number of young populations, their employment at a later stage and their sexual and reproductive health needs throughout their reproductive age span. Indeed, a substantial number of young people has entered their reproductive ages during the last two decades (United Nations Population Division 2003). It is estimated that the size of young-age populations will continue to increase in sub-Saharan Africa, South and West Asia and the Arab region until 2015 (United Nations Population Division 2005). Second, limited schooling and employment opportunities force migration and change the size and composition of cities. Giant cities have appeared during the last twothree decades in many developing countries due to this effect. Rapid urbanisation without planning puts greater financial and physical restraints on education, health and social services if these services cannot keep pace with increasing demand (Vlahov D & Galea S 2002). Even in the developed-country cities, population growth has been reported to increase costs of providing public services as well as to reduce service levels (Ladd HF 1992). In resource-poor settings where this increase cannot be fully accommodated, the burden can be higher. For example, in United Republic of Tanzania, the change in literacy rates from 90% in 1986 to 68% in 1995 was attributed to rising school fees due to structural adjustments (Richey LA 2003). Finally, rapid population growth increases existing socio-economic inequalities within countries because poorer people tend to have more children. An analysis of 62 countries reported that this association is particularly stronger in middle-income countries (Kremer M & Chen D 2002). Another study of 68 countries concluded that the large 6 fertility differentials within countries lower the growth rate of human capital and that it is not the population growth but the distribution of fertility within the population which is actually important for human development (De la Croix D & Doepke M 2002). Nations with rapid population growth have high numbers of young age-groups that place a heavy demand on schooling and employment opportunities Failure to meet demands for employment of the working-age populations forces migration – further stretching the capacities of public services needed to build human capital Rapid population growth increases existing socio-economic inequalities because poorer people tend to have more children The role of reproductive health The evidence indicates that rapid population growth characterized by high fertility in least-developed countries and unequal distribution of fertility due to differentials in fertility rates between rich and poor in middle-income countries have significant implications for the attainment of the MDGs in these countries. In addition, consequences of population growth in terms of altered age-distribution, rapid urbanisation and increased socio-economic inequalities have resource implications for both leastdeveloped and middle-income countries with respect to accumulation of the human capital crucial for development. A clear need to focus on reproductive health exists in all cases. In cases of persisting high fertility, either at the overall population level or in certain segments of the population, services should be able to respond both when high fertility is due to limited availability of effective family planning methods - or information about them - or when other interventions such as education or employment opportunities increase women’s demand for family planning. In the cases where composition of the population changes due to rapid growth, the needs of an increasing number of people of reproductive age should be met to enhance human potential. Programmatic responses in these circumstances include not only meeting family planning needs but also addressing other reproductive health issues which could pose a high burden on individuals, particularly women, if not appropriately dealt with. For example, unsafe sex is the second leading risk factor to health (Ezzati M et al. 7 2002). More than half a million of women die each year due to pregnancy-related causes (WHO 2004) and more than half of the nearly five million new HIV infections each year occur among 15-24 year olds (UNAIDS 2005). Access to reproductive health care for populations as defined at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994 is therefore a key intervention to address the causes as well as consequences of population growth. It facilitates reduction of high fertility levels in populations ready for the second stage of demographic transition as well as strengthens human capital by reducing the burden due to high fertility, unplanned fertility, complications of pregnancies and childbirth, and sexually transmitted infections including HIV. Addressing these conditions has important implications for development by enhancing human potential. Increased focus on reproductive health therefore will accelerate achievement of all MDGs as also suggested earlier (Sachs & McArthur 2005). Both causes (high fertility) and consequences (restraints in building human capital) of rapid population growth need to be addressed through increased attention to sexual and reproductive health, in particular family planning By meeting family planning and sexual and reproductive health needs of individuals, societies are better able to build human capital, hence socio-economic development It should be noted that improving other aspects of human capital, for example, in terms of education, women’s status or environmental sustainability would also contribute to overcome some of the problems of population growth. Indeed, the MDGs aim to promote improvements in each of these areas. Efforts to achieve all MDGs (and to increase attention to sexual and reproductive health) would assist building human capital as well as translating it into sustainable human development. This means distribution of human capabilities both to the future generations (e.g., the influence of maternal education and health on the well-being of the next generation, environmental sustainability) and to the poor and disadvantaged segments of the population (e.g., addressing health inequalities, policies to improve the status of women) (Anand S & Sen A 2000). 8 These complex and inter-related linkages between population issues and the MDGs will not be detailed here, but highlights will be given below on how attention to reproductive health could contribute to achievement of goal 3 (women’s empowerment and gender equality), goal 5 (improving maternal health), and the part of goal 6 on combating HIV/AIDS. Reproductive health and achieving selected MDGs Although women's ability to control their fertility is by itself not sufficient to gaining their full empowerment and achieving gender equality, it is the first and the most important step (Oppenheim K 2005). Women who are able to control their fertility are more likely to be educated and work outside the home. In addition, in the long run, this could help changing the traditional roles that cultures currently assign to women, such as looking after the children and the household, leaving more power-bearing activities to men. In certain settings, high fertility was shown to be related to assigning lower household resources for girls (Anand S & Morduch J 1996). Decreased fertility could partly reverse these trends, thus helping populations to move towards the achievement of goal 3. For goal 5 and HIV/AIDS section of goal 6, reproductive health care is crucial. For example, an analysis of 79 less developed countries demonstrated that the presence of health attendants at birth, contraceptive prevalence, age at marriage and total fertility were among the significant predictors of maternal mortality (Shen & Williamson 1999). The use of modern family planning methods has been shown to prevent unintended pregnancies and, therefore, their possible complications (Chiou Chiun F et al. 2003; Cleland J & Ali MM 2004; Gallo MF et al. 2005; Peterson HB et al. 1996; UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction 1997; Angeles G et al. 2004). It is estimated that at least a quarter of maternal deaths would be avoided if women were able to avoid unplanned pregnancies (Freedman et al. 2005). A range of other elements of reproductive health care such as antenatal, delivery and postnatal care, prevention of complications of unsafe abortion, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections including HIV, have direct impact on improved maternal health. 9 The effective prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, is an integral component of sexual and reproductive health services. There is a strong association between sexually transmitted infections and HIV infection (Cameron DW et al. 1989; Laga M et al. 1993) and there is biological evidence that the presence of a sexually transmitted infection increases (and treatment of an existing sexually transmitted infection reduces) acquisition of HIV (Cohen MS et al. 1997; Robinson NJ et al. 1997). The family planning component of reproductive health services is also crucial in reducing the number of new HIV cases among women and children. Recently, an in-depth analysis from eight African countries with severe epidemics demonstrated that for prevention of HIV in infants, the current focus on prevention of transmission of the virus from mothers to infants using antiretroviral drugs is less effective than achieving small reductions in maternal HIV prevalence or in unintended pregnancy among women with HIV (Sweat MD 2004). Indeed, family planning services in sub-Saharan Africa may be preventing more HIV infections than the provision of antiretroviral drugs does (Reynolds HW et al. 2005). Providing universal access to effective reproductive health care is therefore, essential for improving maternal health (reach goal 5) and tackling HIV/AIDS (reach goal 6). It should be noted that better care for women during pregnancy and at the time of delivery will also have a positive impact on newborn health and thus contribute to the achievement of goal 4 on reducing child mortality (Darmstadt GL et al. 2005; Feresu S et al. 2005). Increased focus and investment in sexual and reproductive health will accelerate achievement of all MDGs Women's ability to control their fertility is the first and the most important step for their empowerment, therefore achievement of goal 3 Universal access to effective reproductive health care is fundamental to improving maternal health (reach goal 5) and tackling HIV/AIDS (reach goal 6) and will also contribute to reducing newborn and hence child mortality (reach goal 4) Conclusion Population growth is still a problem in countries where socio-economic development is also far from the desired level. The cause in most of the least-developed countries is persisting high fertility. Despite having lowered their fertility levels, middle- 10 income countries demonstrate unequal distribution of fertility with higher fertility in poorer segments of the population, which increases socio-economic inequalities. Consequences of population growth can potentially restrain investments in human capital, such as the education, the creation of employment opportunities and the provision of sexual and reproductive health care services that are crucial to fulfilment of all MDGs. Increased focus on provision of sexual and reproductive health care is needed to address both the underlying causes in least-developed and middle-income countries and the dynamics of the consequences of population growth if human well-being and development (and MDGs) are to be reached. 11 References 1. Ahituv A (2001) Be fruitful or multiply: on the interplay between fertility and economic development. J Popul Econ 14, 51-71. 2. Anand S and Morduch J (1996) Poverty and the population problem. Unpublished work. 3. Anand S & Sen A (2000) Human development and economic sustainability. World Development 28, 2029-2049. 4. Angeles G, Guilkey DK, & Muroz TA (2004) The effects of education and family planning programs on fertility in Indonesia. Carolina Population Center. Chapel Hill. 5. Barlow R (1994) Population growth and economic growth: some more correlations. Popul Dev Rev 20, 153-165. 6. Barro RJ (2001) Human capital and growth. Am Econ Rev 91, 12-17. 7. Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, Ronald AR, Maitha GM, & Gakinya MN (1989) Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet 334, 403-407. 8. Chiou Chiun F, Trussell J, Reyes E, Knight K, Wallace J, Udani J, Oda K, & Borenstein J (2003) Economic analysis of contraceptives for women. Contraception 68, 3-10. 9. Cleland J & Ali MM (2004) Reproductive consequences of contraceptive failure in 19 developing countries. Obstet Gynecol 104, 314-320. 10. Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, Kazembe P, Dyer JR, & Costello Daly C (1997) Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. Lancet 349, 18681873. 11. Crook N (1996) Population and poverty in classical theory: testing a structural model for India. Popul Stud 50, 173-185. 12. Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, & de Bernis L (2005) Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 365, 977-988. 13. Davis K (2006) Population policy: will current programs succeed? Science 158, 730-739. 14. De la Croix D and Doepke M (2002) Inequality and growth: why differential fertility matters? Department of Economics, UCLA. Working paper. 12 15. Eastwood R & Lipton M (2001) Demographic transition and poverty: effects via economic growth, distribution and conversion. In: Birdsdall N, Kelley AC, and Sinding SW (Eds) Population matters: Demographic change, economic growth, and poverty in the developing world. Oxford University Press, New York. 16. Ehrlich PR (1968) The population bomb. Ballantine Books, New York. 17. Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, & Murray CJL (2002) Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 360, 13471360. 18. Feresu S, Harlow S, Welch K, & Gillespie B (2005) Incidence of stillbirth and perinatal mortality and their associated factors among women delivering at Harare Maternity Hospital, Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 5,9. 19. Freedman LP, Waldman RJ, de Pinho H, Wirth ME, Chowdhury AMR, & Rosenfield A (2005) Transforming health systems to improve the lives of women and children. Lancet 365, 997-1000. 20. Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, & Schulz KF (2005) Twenty micrograms vs. >20 micrograms estrogen oral contraceptives for contraception: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception 71, 162-169. 21. Kelley AC (1988) Economic consequences of population change in the third world. J Econ Lit 26, 1685-1728. 22. Kelley AC & Schmidt RM (1995) Aggregate population and economic growth correlations: the role of components of demographic change. Demography 32, 542555. 23. Kelley AC & Schmidt RM (2001) Economic and demographic change: a synthesis of models, findings, and perspectives. In: Birdsdall N, Kelley AC, and Sinding SW (Eds) Population matters: Demographic change, economic growth, and poverty in the developing world. Oxford University Press, New York. 24. Kibirige JS (1997) Population growth, poverty and health. Soc Sci Med 45, 247-259. 25. Kremer M & Chen D (2002) Income distribution dynamics with endogenous fertility. J Econ Growth 7, 227-258. 26. Ladd HF (1992) Population growth, density and the costs of providing public services. Urban Stud 29, 273-295. 27. Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M, Malele B, Tuliza M, & Nzila N (1993) Nonulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort study. AIDS 7, 95-102. 13 28. Malthus TR (1999) Essay on the principle of population. Oxford University Press, New York. 29. McNicoll G (1984) Consequences of rapid population growth: an overview and assessment. Popul Dev Rev 10, 177-240. 30. Oppenheim K (2005) Contribution of the ICPD Programme of Action to gender equality and the empowerment of women. Seminar on the relevance of population aspects for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York. 31. Orbeta AC (1992) Population growth, human capital expenditures and economic growth: a macroeconometric analysis. Philipp Rev Econ Bus 29, 179-230. 32. Peterson HB, Hughes JM, Wilcox LS, Tylor LR, & Trussell J (1996) The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization: findings from the US Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174, 1161-1168. 33. Raleigh VS (1999) World population and health in transition. BMJ 319, 981-984. 34. Reynolds HW, Steiner MJ, & Cates Jr W (2005) Contraception's proved potential to fight HIV. Sex Trans Inf 81, 184-185. 35. Richey LA (2003) Women's reproductive health & population policy: Tanzania. Rev Afr Polit Econ 96, 273-292. 36. Robinson NJ, Mulder DW, Auvert B, & Hayes RJ (1997) Proportion of HIV infections attributable to other sexually transmitted diseases in a rural Ugandan population: simulation model estimates. Intl J Epidemiol 26, 180-189. 37. Rosenzweig MR (1990) Population growth and human capital investments: theory and evidence. J Polit Econ 98, S38-S70. 38. Sachs JD & McArthur JW (2005) The Millennium Project: a plan for meeting the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet 365, 347-353. 39. Sahn DE and Stifel DC (2002) Progress toward the Millennium Development Goals in Africa. Cornell University. Working paper. 40. Sen A (1994) Population: delusion and reality. NY Review of Books 41, 62-71. 41. Shen C & Williamson JB (1999) Maternal mortality, women's status, and economic dependency in less developed countries: a cross national analysis. Soc Sci & Med 49, 197-214. 42. Strulik H (2005) The role of human capital and population growth in R&D based models of economic growth. Rev Int Econ 13, 129-145. 14 43. Sweat MD (2004) Cost-effectiveness of nevirapine to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in eight African countries. AIDS 18, 1661-1671. 44. UNAIDS (2005) AIDS epidemic update. December 2005. UNAIDS, Geneva. 45. UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (1997) Long-term reversible contraception: twelve years of experience with the TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception 56, 341-352. 46. United Nations General Assembly (2000) United Nations Millennium Declaration. A/RES/55/2. September 2000. UN General Assembly, 55th session agenda item 60(b). 47. United Nations Population Division (2003). World Population Monitoring. Reproductive rights and reproductive health. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York. 48. United Nations Population Division (2005) World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision: Highlights. ESA/P/WP.193. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York. 49. Vlahov D & Galea S (2002) Urbanization, urbanicity and health. J Urban Health 79, 51-62. 50. WHO (2004) Maternal mortality in 2000. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. World Health Organization, Geneva. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. 15