word version

advertisement

http://www.geog.ubc.ca/iiccg/papers/Swyngedouw_E.html

Erik Swyngedouw

School of Geography

Oxford University

Oxford OX1 3TB

Tel: 01865-271901

FAX: 01865-271929

e-mail: erik.swyngedouw&geog.ox.ac.uk (&=@)

MODERNITY AND HYBRIDITY

THE PRODUCTION OF NATURE: WATER AND

MODERNISATION IN SPAIN

"I am planning something geographical" (Klaus Kinski in Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo)

"Soon the enlightened nations will put on trial those who have hitherto ruled over them. The kings shall flee into the

deserts, into the company of the wild beasts whom they resemble; and Nature shall resume her rights" (Saint-Jus, Sur la

Constitution de la France, Discours prononcé à la Convention du 24 Avril 1793).

"The Hydraulic ordering of the territory constitutes a structural necessity of Spanish society as an industrial society "

(Alfonso Ortí, 1984: 11)

1. INTRODUCTION: THE PRODUCTION OF NATURE

Spain is arguably the European country where the water crisis has become most acute in recent years. Since 1975, demand

for water has systematically outstripped supply and, despite major and unsustainable attempts to increase pumping of

ground water and to develop a more intensive use of surface water, the problem has intensified significantly. The recent

1991-1995 drought, which affected most of Central and Southern Spain, spearheaded intense political debate, particularly

as the cyclical resurgence of diminished water supply from rainwater coincided with the preparation of the Second National

Hydrological Plan (Ruiz, 1993; Gómez Mendoza and del Moral Ituarte, 1995; del Moral Ituarte, 1996). Throughout this

century, water politics, economics, culture and engineering have infused and embodied the myriad tensions and conflicts

that drove and still drive Spanish society.

The political and economic history of Spain over the past century has been a tumultuous one. Arguably, the waves of

social, cultural, environmental and political change that have characterised Spain's modernisation drive are among the most

dramatic in Europe. Although the significance of water on the Iberian peninsula has attracted considerable scholarly and

other attention, the central role of water politics, water culture and water engineering in shaping Spanish society on the one

hand, and the contemporary water geography and ecology of Spain as the product of centuries of socio-ecological

interaction on the other have remained largely unexplored. Yet, very little, if anything, in today's Spanish social, economic

and ecological landscape can be understood without explicit reference to the changing position of water in the unfolding of

Spanish society. The hybrid character of the water landscape (the waterscape) comes to the fore in Spain in clear and

unambiguous manners. Hardly any river basin, hydrological cycle or water flow has not been subjected to some form of

human intervention or use; not a single form of social change can be understood without simultaneously addressing and

understanding the transformations of and in the hydrological process. The socio-natural production of Spanish society, I

maintain, can be clearly illustrated by means of the excavation of the central role of water politics and engineering in the

making of Spain's modernisation process.

I intend to situate the present political-ecological processes around water in Spain in the context of what Neil Smith (1984)

defined as 'the production of nature'. In particular, I shall argue that the tumultuous process of modernisation in Spain and

the contemporary condition, both in environmental and political-economic terms, is wrought from historical spatialecological transformations. Modernisation in Spain was a decidedly geographical project and became expressed in and

through the intense spatial transformation of Spain this century; a transformation in which water and the waterscape was

and is playing a pivotal role. The contradictions and tensions inherent in the process that is commonly referred to as

'modernisation' are, I maintain, expressed by and worked through the transformation of nature and society. The 'modern'

environment and waterscape in Spain, therefore, is what Latour would refer to as a 'hybrid', a thing-like appearance ( a

'permanence' as Harvey (1996) would call it), part natural part social, that embodies a multiplicity of historical-geographical

relations and processes that are simultaneously and inseparably natural and social.

The paper is divided into two parts. In the first part, I seek to develop a theoretical/methodological perspective which is

explicitly critical of traditional perspectives that tend to separate various aspects of the hydrological cycle into discrete and

independent objects of study. The traditional hydrological, engineering, geographical, political, sociological, economic and

cultural perspectives on water -- with a strong dominance of engineering and economic aspects -- have produced a

particular piecemeal perspective which feed a particular water-ideology, but which seems to be increasingly less able to

contribute in creative and innovative ways to mitigate the growing problems associated with contemporary water practices

(Ward, 1997). My perspective, broadly situated in the political-ecology tradition, draws critically from recent work

proposed by ecological historians, cultural critics, sociologists of science, critical social theorists and political-economists.

Although mainstream perspectives pay lip-service to considering the hydrological cycle as a complex, multi-faceted and

global network, which includes physical as well as human elements, they rarely overcome the dualisms of the

nature/society divide and continue to isolate parts from the totality (see, for a review, Castree 1995; Demeritt, 1994; Gerber,

1997). My main objective is to bring together what has been severed for too long by insisting that nature and society are

deeply intertwined. The view of 'Socio-Nature' as a process of production and construction has major consequences for

political strategy. As Lewontin (1997: 137-138) insists, "the constructionist view of organism and environment is of some

consequence to human action. A rational environmental movement cannot be built on the demand to save the environment,

which, in any case, does not exist ... Remaking the world is the universal property of living organisms and is inextricably

bound up with their nature. Rather, we must decide what kind of world we want to live in and then try to manage the

process of change as best we can approximate it".

In the second part, we intend to excavate the origins of Spain's 20th century modernisation process as expressed in debates

and actions around the hydrological condition. The conceptual framework presented in the first part will structure a

narrative that weaves the network of socio-natural relations in ways that permit the recasting of modernity as a deeply

geographical, although by no means coherent, homogeneous, total or uncontested project. If the social and the natural

cannot be severed, but are intertwined in perpetually changing ways in the production process both of society and of the

physical environment, then the rather 'opaque' idea of 'the production of nature' may become clearer. In sum, I seek to

document how both 'the socio-natural' is historically produced to generate a particular geographical configuration that

provides the foundation and ferment for the making of contemporary practices and debates.

2. ON HYBRIDS AND SOCIO-NATURE: FLOW, PROCESS AND DIALECTICS.

'Natural' or 'ecological' conditions and processes do not operate separately from social processes and the actually existing

socio-natural conditions are always the result of intricate transformations of pre-existing conditions which are themselves

inherently natural and social. For example, David Harvey (1996) insists that there is nothing particularly unnatural about

New York. Cities, regions or any other socio-spatial processes or condition are a network of interwoven processes that are

simultaneously human, natural, material, cultural, mechanical and organic. The myriad of processes that support and

maintain social life, such as, for example, water, energy, food, computers, etc... always combine society and nature in

infinite ways; yet simultaneously, these hybrid socio-natural 'things' are full of contradictions, tensions and conflicts. They

are those proliferating objects that Donna Haraway calls 'Cyborgs' or 'Tricksters' (Harraway, 1991) or that Bruno Latour

refers to as 'Quasi-Objects' (Latour, 1993); these hybrid, part social/part natural -- yet deeply historical and thus produced -objects/subjects are intermediaries that embody and express nature AND society and weave a network of infinite

transgressions and liminal spaces. For example, if I were to capture some water in a cup and excavate the networks that

brought it there and follow Ariadne's thread through the water, 'I would pass with continuity from the local to the global,

from the human to the non-human' (Latour, 1993: 121).

These flows would narrate many interrelated tales: the story of social groups and classes, and the powerful socio-ecological

processes that produce social spaces of privilege and exclusion, of participation and marginality, of chemical, physical and

biological reactions and transformations, of the global hydrological cycle and global warming, of the capital, machinations

and strategies of dam builders, of urban land developers, of the knowledges of the engineers, of the passage from river to

urban reservoir, of the geo-political struggle between regions and nations. In sum, water embodies multiple tales of socionature as 'hybrid'. The rhizome of underground and surface water flows, of streams, pipes and canals that come together in

water gushing from fountains, taps and irrigation channels is a powerful metaphor for the socio-ecological processes

constituting social life and nature .

The excavation of the production of these hybrid networks and their proliferation with the intensification of the

modernisation process implies a constructionist view in both a material and discursive sense. In 'Grundrisse' and in

'Capital', Marx insisted on the 'natural' foundations of social development. Any materialist approach necessarily adheres to

a perspective which insists that 'nature' is an integral part of the 'metabolism' of social life. Social relations operate in and

through metabolising the 'natural' environment which, in turn, transform both society and nature and produce altered or new

socio-natural forms (see Grundman, 1991; Benton, 1996). Whilst 'Nature' (as a historical product) provides the foundation,

social relations produce nature's and society's history. Of course, the ambition of classical Marxism was wider than

reconstructing the dialectics of historical socio-natural transformations and their contradictions. It also insisted on the

ideological notion of 'nature' in 'bourgeois' science and society and claimed to uncover Truth through the excavation of

'underlying' socio-ecological processes (Schmidt, 1971; Benton, 1989). However, by concentrating on the labour process

per se, many Marxist analyses tended to replicate the very problem it meant to criticise. In particular, by rendering nature as

the substratum for the unfolding of social relations, especially labour relations, they maintained the material basis for social

life, while relegating 'natural processes' to a realm outside of social life.

We encounter an interesting paradox here. Insisting on the 'social production of nature' suggests that social relations

'determine in the last instance' the production process. This might easily lead to the illusion that all processes-in-nature are

subsumed under social control and, consequently, to the view of a manageable and subordinated primordial and external

nature whose metabolism remains 'outside' the social and discursive. Nature itself belongs to the 'pure' domain of the

natural and becomes just 'tainted' and 'transformed' by the social. The social and the natural may have been brought together

and made historical and geographical by Marx, but in ways that keep both as a-priori separate domains. Not the networks

that constitute and the processes that produce 'socio-natural' hybrids are reconstructed, but rather the social and the natural

are seen as two contradictory, yet complementary, poles that construct a 'reality' which is itself muddled and needs to be

'purified' by isolating and separating (both in thought and in praxis) things natural and things social.

I would argue, with Latour (1993), that this process of 'purification' resides in the conceptual, deeply (non-)modernist,

apparatus and discursive construction of the world into two separate, but profoundly interrelated (and this is exactly the

way in which the theoretical debate left and right and much of green is organised) realms, i.e. nature and society, between

which a dialectical relationship unfolds. The debate, then, becomes a dispute about the nature of the relationship, its

implications and the absence/presence of some ontological foundation. The argument runs more or less as follows. Humans

encounter nature with its internal dynamics, principles and laws as a society with its own organising principles. This

encounter inflicts consequences on both. The dialectic between nature and society becomes an external one, i.e. a

conflicting relationship between two separate fields, nature and society, mediated by material, ideological and

representational practices. The product, then, is the thing (object or subject) that is produced out of this dynamic encounter.

Neil Smith (1984; 1996), in contrast, insisted that nature is an integral part of a 'process of production' or, in other words,

society and nature are integral to each other and produce in their unity permanencies (or thing-like moments). The notion of

the 'production of nature', borrowed and re-interpreted from Lefebvre ((1974)1991), suggests that socio-nature itself is a

historical-geographical process (time/place specific), insists on the inseparability of society and nature and maintains the

unity of socio-nature as a process. In brief, both society and nature are produced, hence malleable, transformable and

transgressive. Smith does not suggest that all non-human processes are socially produced (although he insists that all nature

(including social nature) is a historical-geographical process (see also Levins and Lewontin, 1985; Lewontin, 1993), but

argues that the idea of some sort of pristine nature (First Nature in Lefebvre's account) becomes increasingly problematic as

new 'nature' (in the sense of different forms of 'nature') is produced over space and time. It is this historical-geographical

process that led Haraway and Latour to argue that the number of hybrids and quasi-objects proliferates and multiplies.

Indeed, from the very beginning of human history, but accelerating as the 'modernisation' process intensified, the objects

and subjects of daily life became increasingly more socio-natural. Consider, for example, the socio-ecological

transformations of entire ecological systems (through agriculture, for example), sand and clay metabolised into concrete

buildings through the labour process, the acceleration and ever expanding socio-ecological footprint of the urbanisation

process or the contested production of new genomes (such as Oncomousetm (Haraway, 1997)). Of course, the production

process of socio-nature includes both material processes (edifying constructs or producing new genetic sequences) as well

as proliferating discursive and symbolic representations of nature. As Lefebvre (1991) insisted, the production of nature

transcends material conditions and processes; it is also related to the production of discourses of nature (by scientists,

engineers and the like) on the one hand, and of powerful images and symbols (virginity, a moral code, originality, 'survival

of the fittest', wilderness, etc. ...) through which 'Nature' becomes represented on the other.

If we maintain a view of dialectics as internal relations (Olman, 1993; Balibar, 1995; Harvey, 1996), we must insist on the

need to transcend the binary formations of 'nature' and 'society' and develop a new 'language' which maintains the

dialectical unity of the process of change as embodied in the thing itself. "Things" are hybrids or quasi-objects (subjects and

objects, material and discursive, natural and social) from the very beginning. In this introduction, I shall use, for better or

for worse, political-ecology to capture this process of the production of networks and socio-nature to refer to the product,

the hybrid, the quasi-object. By this I mean that the 'world' is a historical-geographical process of perpetual metabolism in

which 'social' and 'natural' processes combine in a historical-geographical 'production process of socio-nature', whose

outcomes (historical nature) embody chemical, physical, social, economic, political and cultural processes in highly

contradictory but inseparable manners. Every body and thing is a mediator, part social part natural but without discrete

boundaries, which internalises the multiple contradictory relations that re-define and re-work every body and thing.

For Lefebvre, capturing space or socio-nature from a dialectical and emancipatory perspective, implies constructing

multiple narratives that relate material, representational and symbolic practices, each of which have a series of particular

characteristics and internalises the dialectical relations defined by the other 'domains', but none of which can be reduced to

the other (Lefebvre, 1991). In short, Lefebvre's triad opens up an avenue for enquiry which insists on the 'materiality' of

each of the component elements, but whose content can be approached only via the excavation of the metabolism of their

becomings, in which the internal relations are the signifying and producing mechanisms. Put simply, Lefebvre insists on the

ontological priority of process and flux which become interiorized in each of the moments (lived, perceived, conceived) of

the production process, but always in a fleeting, dynamic and transgressive manner. Whether we discuss the global

hydrological cycle or the symbolic meanings of nature to city folks, it is the stories of the process of their perpetual reworking that broaches their being as part of a process of continuous transformation in which the stories themselves will

subsequently take part. Following Ariadne's thread through the Gordian knot of socio-nature's networks -- as Latour

suggests -- is not good enough if stripped from the process of their historical-geographical production. Hybridisation is a

process of production, of becoming, of perpetual transgression. Lefebvre's insistence on temporality(ies), combined with

Latour's networked (re)construction of quasi-objects, provides a glimpse of how such a research programme might be

practised.

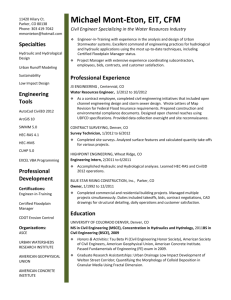

Figure 1 summarises this argument. None of the component parts is reducible to the other, yet their constitution arises from

the multiple dialectical relations that swirl out from the production process itself. Consequently, the parts are always

implicated in the constitution of the 'thing' and are never outside the process of its making. In sum, then, political-ecology is

a process based episteme in which nothing is ever fixed or, at best, fixity is the transient moment that can never be captured

in its entirety as the flows perpetually destroy and create, combine and separate. The dialectical perspective also insists on

the non-neutrality of relations in terms of both their operation and their outcome and, finally, distinct categories (nature,

society, city, species, water, etc...) are the outcome of the infusion of materially-discursive practices which are each time

creatively destroyed in the very production process of socio-nature.

Insert Figure 1 about here

Where does this lead us, then, in terms of approaching the political-ecology of water? A few conclusions come readily to

mind. First, although we cannot escape the 'thing' or 'the product', transformative knowledges about the 'product' can only

be gauged from reconstructing its processes of production. Second, there is no 'thing-like' ontological or essential

foundation (society, nature or text) as the process of becoming and of hybridisation has ontological and epistemological

priority. Third, as every 'thing-cyborg' internalises the multiple relations of its production, any 'thing' can be entered as the

starting point for undertaking the archaeology of her/his/its socio-natural metabolism (the production of her/his/its socionature). Fourth, this archaeology has always already begun and is never ending (cf. Althusser's infamous 'history as a

process without a subject'), always open, contested and contestable. Fifth, this perspective does not necessarily lead to a

relativist position given the non-neutrality and intensely powerful forces through which socio-nature is produced. Every

archaeology and associated narratives and practices are always implicated in and consequential to this very production

process. Knowledge and practice are always 'situated' in the web of (power) relations that defines and produces socionature. Sixth, the notion of a socio-natural production process transcends the binary distinctions between society/nature,

material/ideological and real/discursive.

Of course, reconstructing the production processes of socio-natural networks along the lines presented above is hard to do.

Yet, I would maintain that such perspective has profound implications for understanding the relationship between

capitalism, modernity, ecology, space and contemporary social life and for transformative emancipatory ecological politics.

In the next part, we shall explore this perspective further from the vantage point of the circulation of water and the

transformation of Spain's waterscape.

3. THE PRODUCTION OF NATURE: WATER AND MODERNISATION IN SPAIN.

I shall not start analysing the Spanish water map from the available hydrological data and the physical characteristics of the

water basins. Surely, this is important, but prioritising this would miss the central tenet of the argument outlined above.

Indeed, these very physical conditions and characteristics are not absolute, stable, God-given characteristics. On the

contrary, the history of Spain's modernisation has been a history of altering, redefining and transforming these very

physical characteristics. In fact, the hydrological characteristics have been infused with social practices, cultural meanings

and engineering principles for a very long time. For example, a stroll through Granada's Alhambra gardens, built by the

Islamic rulers that controlled this part of Spain until the 15th century, provides a particularly attractive and material vision

of how water, culture and social construction combine in and are expressed by the transformation and metabolisation of the

flow of water.

However, it was not until the late 19th century that the socio-natural production process of contemporary Spain accelerated.

From that moment onwards, Spain -- belatedly, somewhat reluctantly and almost desperately -- launched itself on a path of

accelerating modernisation. Of course, modernisation through socio-natural changes always takes place within already

constructed historical socio-natural conditions. On occasion, we shall refer to and highlight these conditions. For the

present purposes, i.e. to document and substantiate the notion of the 'production of nature' on the one hand and to bring out

how Spain's modernisation process became (and still is) a deeply geographical project, it will suffice to chart the

tumultuous, contradictory and often very complex historical-geography of Spain's modernisation though water engineering.

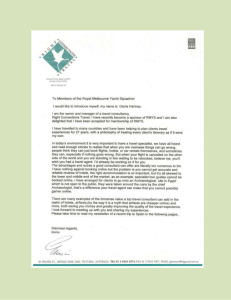

Today, the country has almost 900 dams, more than 800 of which have been constructed this century alone (see Table 1).

Not a single river basin has not been altered, managed, engineered and transformed. Water has been an obsessive theme in

Spain's national life this century and the quest for water continues to go on unabated. The present discussions in Spain over

the Second National Hydrological Plan and the relentless demands of cities, regions and industries for ever more water are

testimony to a continuing and ever intensifying conflict and struggle over the trajectory of Spain's modernisation process.

Insert Table 1 about here

I shall explore the Spanish condition at the turn of the century when a distinct discourse and rhetoric of modernisation

emerged. This modernisation drive which permeated through the whole of Spanish society and would be generate the

anchoring framework for key social, political, cultural and technical debates and practices until the present day. The

modernising desires of broad strata of Spanish society considered the social production of nature as the pivotal element

around which the construction of hegemonic social and political visions could be attempted. The dialectics of

modernisation as expressed in Spain's hydro-politics will be documented with an eye towards identifying the relationship

between the process of production of a 'new' nature and the ebb and flows of dominant political-economic hegemonies.

Multiple narratives that move around the spiral presented in figure 1 will be woven together to reconstruct the relations of

power inscribed in the discursive, ideological, cultural, material and scientific practices through which the Spanish

waterscape became constructed and reconstructed as a socio-natural space reflecting Spain's contested modernisation

process and the relations of power inscribed therein.

3.1. Spain's post-colonial shock.

Whilst other European imperialist countries were consolidating their geographical expansion overseas at the end of the 19th

century, the Spanish traditional elites found themselves in a highly traumatic condition with the loss of their last colonial

possessions (Cuba and the Philippines) after a disastrous 'war of independence'. Faced with a mounting economic crisis,

rising social tensions and an antiquated and still largely feudal social order that was lamenting the military colonial defeat,

Spanish 'progressive' cultural, professional, political and intellectual elites were desperately searching for a way to revive or

to 'regenerate' the nation's social and economic base (Ortega Cantero, 1995). This drive to revive the nation's 'spirit' and

which became known as 'el regeneracionismo' -- a theme that quickly became an 'obsessive theme in national life'

(Fernández Almagro, 1970: 239) -- produced a rich, albeit ambiguous and by no means homogeneous, ferment from which

Spain would launch itself onto a path of modernisation; a process which the traditional elites and their parasitic dependence

on colonial exploitation had hitherthen and largely successfully prevented or at least stalled. The various regeneracionist

tendencies at the time shared a number of views: a concern with the 'decadence' of Spain, a desire to re-generate the

national 'spirit' and a search for a bedrock to permit national revival (for examples, see Mallada, 1890; Macías Picavea R,

1899, Isern, 1899; Costa, 1900). While many of the participants centred this revival around the mobilisation of the 'natural

riches and resources' of the country (Gómez Mendosa, 1992: 233), 'el regeneracionismo' also emphasised the intellectual

and moral revitalisation of the people and the associated need for educational and scientific 'progress'. This programme

became formulated as a military-geographic project, which Joaquin Costa (1900: 13) summarises as follows :

"The mischief of Spain originated principally because of the absence in national consciousness of the vision that the

internal war against drought, against the rugged character of the soil, the rigidity of the coasts, the intellectual

backwardness of the people, the isolation from the European Centre, the absence of capital, was of greater importance than

the war against Cuban or Filipino separatism; and because of not having been as alarmed by the former as by the latter,

and because of not having made the same sacrifices that were made for the latter, and of not having committed -- sad

suicide -- the same stream of gold to the engineers and scientists as to the admirals and generals." (cited in Gómez

Mendosa, 1992: 233) (my emphasis).

In the absence of an external geographical project as the foundation to modernisation, therefore, the Spanish modernising

elites concentrated on a national programme; a programme which would be equally deeply geographical and founded on the

radical transformation of Spain's geography and, in particular, its water resources (Gómez Mendoza and Ortega Cantero,

1987). While imperial countries pursued strategies of external spatial solutions, Spain was forced to revolutionise its

internal geography and to produce new geographical configurations if it was to keep up with its expansionist northern

European rivals. This programme of revolutionising Spain's geography and the production of a new space embodied

physical, social, cultural, moral and aesthetic elements and fused around the then dominant and almost hegemonic ideology

of national development, revival and 'progress'.

3.2. Modernisation as a geographical project: the production of space/nature.

The dominant form of socio-economic development in Spain until the late 19th century had combined colonial trade with

domestic farming. The latter was based on large estate dryland culture by (mainly Southern) latifundistas whose economic

position depended on a protectionist economic stance. The effects of an increasingly liberalised international trade,

combined with the loss of the last Spanish colonies, led to disastrous socio-economic conditions and rapidly rising social

conflicts along a myriad of ruptures and intensified already sharp social tensions on the countryside (Garrabou, 1975;

Fontana, 1975) .The traditional agricultural elites were faced with the emergence of modernising elites, both agricultural

and industrial, which began to challenge the political-economic and ideological dominance of the latifundistas. The

proletarianization process, combined with sharpening crisis conditions, intensified class struggle both in the city and on the

countryside. Industrialisation (mainly in the North) intensified the city/countryside divide and accentuated even more

already long standing inter-regional conflicts. Containing and working through these tensions without revolutionary

transformation necessitated a vision around which the modernising social groups could ally via a project of national

regeneration. This revitalisation, which became formulated as a project of geographical restructuring, combined major

environmental change, socio-economic restructuring and moral revival, linked together in a regeneracionist ideological

discourse. This national geographical project would revolve around the hydrological/agricultural nexus. The geographical

'problem' became the axis around which both the socio-cultural and economic malaise was explained and where the course

of action resided.

One of the key protagonists and interlocutors who articulated this revival desire through modernisation was Joaquin Costa

who in 1892 wrote that State organised hydraulic politics should be a national objective "capable of reworking the

geography of the Fatherland and of solving the complex agricultural and social problems" (Costa, 1975(1892): 88). The

fusion of producing a new geography and revolutionising the internal operation of the State would mitigate social tensions

and provide the basis for a pro-modernist and popular petty-production based development process (Orti, 1994). This focus

on a geographical project as the foundation for modernisation permitted progressive elites to raise the social problem (class

struggle, economic decline, mass unemployment) without formulating it in class terms. This, in turn, enabled the gradual

formation of an initially weak, but over time growing, coalition of reformist socialists, populists, industrialists and

enlightened agricultural elites to form an hegemonic vision about Spain's future; an alliance hopefully strong enough to

defeat the traditionalists and to keep the revolutionary socialists and anarchists at bay. It would be this hegemonic

modernisation vision (although coalitions, objectives and means would change over time, the geographical basis for

modernisation would remain the guiding principle) which would become the pivot of Spain's development until the end of

the Franco regime.

The realisation of such an ambitious project of mobilising resources and educating the people demanded thorough

geographical knowledge (of a particular kind). As Gómez Mendosa and Ortega Cantero (1987: 80) argue, "the real

patriotism is the bedrock of the regenaracionist project and this patriotism flows from the exact knowledge of the

geographical reality of the country" (my translation). In 1918, for example, R. Altamira (1923: 168-169) writes how the

description of Spain's geography offers a great lesson in patriotism; and Azorín concludes that "the basis of patriotism is

geography". The only road to confront and solve the national problem is by means of a preoccupation with the problem of

the land, of the physical nature of the territory. Macás Picavea (1895: 346) summarises the relationship between the need

for a scientific geography and the regeneracionist project in a superb manner:

"To rehabilitate us, it is imperative to start with the rehabilitation of our land: this is an essential and absolute condition.

And in order to restore this geographical environment that is our fatherland, who would deny that the first thing to be done

is to know it well and accurately? It is from this that the veritable patriotic character with which the cultivation of Iberian

geography has to present itself in the eyes of all the Spaniards."

In 1930, this vision is still pretty much the leitmotiv for the regeneracionist agenda, which, in fact, would only materialise

on a grand scale after the Civil War. A newly published journal in 1930 recapitulates the great geographical mission of the

modernising agenda with the same vigour and passion: "There is nothing more urgent for our national reconstitution than a

profound study of our geography and our soil. This will be the seed for the great political re-birth of Spain" (N, 1930: 2930).

This project to remake Spanish geography as part of a particular modernisation strategy combined a decidedly political

strategy, a particular ideological vision, a call for a scientific-positivist understanding of the natural world, a scientifictechnocratic engineering mission and a popular base rooted in a traditional peasant rural culture. Plenty of evidence can be

found for this in Costa's work and in that of his contemporaries (Perez De La Dehesa, 1966; Tuñon De Lara, 1971; Orti,

1976). The revolution in the State (but certainly not of the State) through a politics of spatial and environmental

transformation would centre around the defence of the small peasant producer cum landowner, communal (state) control of

water, educational enhancement, technical-scientific control and a leap to power of an alliance of small-holders and the new

bourgeoisie which hitherto had been largely marginalised by the aristocratic land-owning elite and their associated elite

administrators in the State apparatus. At the same time, the focus on restoring or, in fact, expanding land-ownership through

'internal colonisation', fostering growth and concentrating the efforts in an 'organically' organised State allowed to bring

together reformist intellectuals, some worker movements as well as the nascent industrial bourgeoisie in a more or less

coherent vision of reform against the traditionalists. The geographical project became, as such, the glue around which often

unlikely partners could gel while excluding the more radical left winged revolutionaries as well as the 'radical'

conservatives. Surely, the sublimation of the many tensions and conflicts within this loose alliance of reformists through a

focus on re-organising Spain's hydraulic geography served the twin purpose of providing a discursive vehicle to ally

hitherto excluded social groups into a powerful coalition while formulating a project that could contain social tension

without defining the problem purely in class or other conflictuous social relational terms (see Nadal Reimat, 1981). As Orti

(1976: 179) maintains:

"Hydraulic politics, understood in a broad and symbolic sense as a process of accelerated transformation of agriculture from

extensive and traditional into modern and intense, must constitute the fundamental vector of national politics. This must

catalyse an agrarian reform which would permit a balanced economic development and prevent the ongoing process of

proletarianisation of the peasant masses, moderating social polarisation and class struggle".

This organic and anti-revolutionary (in social class terms) reformism in which the State and its internal revolution would

take centre stage to organise the socio-spatial necessary transformation would, after the failed attempts to initiate reform

during the first few decades of the 20th century, provide a substratum on which the later falangist ideology would thrive.

3.3. Water as the lynch-pin to Spain's modernisation drive.

If the 'remaking' of Spain's geography became the great modernising adagio, then, water and hydrological engineering were

its master-tools. The study of geography would bring out the problems of the fatherland and these revolved around fertility,

in terms of both 'the lack of water and the infertility of the soil'. In 1903, Costa wrote that 'the greatest obstacle which

prevents our country to improve production is the absence of humidity in the soil because of insufficient or absent rainfall'

(cited in Ortega, 1975: 37). "Rain rushing to the sea and taking part of the soil with it" was to be avoided at all cost, a

parliamentary document of 1912 stated, repeating the already century old claim (which would be heard again during the

1992/95 drought) that 'not a single drop of water should reach the Ocean without paying its obligatory tribute to the earth'.

Indeed, the dominant view at the time was that "Spain would never be rich as long as its rivers flowed into the sea"

(Maluquer de Motes, 1983: 96). The regeneracionist rhetoric assigned great symbolic value to the often repeated image of

the "mutilating loss of the soil of the Fatherland as a consequence of the 'nature' of the pluvio-fluvial regime". In addition,

both the modernisation of industry and its associated urbanisation and of agriculture generated a real 'water fever'

(Maluquer de Motes, 1983: 84).

Joaquin Costa became one of the prime advocates and potent symbols of this broad social movement for modernisation

through geographical restructuring in which the 'hydrological solution' would be the substratum for fostering growth,

permitting social (land) reform and cultural emancipation (Ortega, 1975). His writings would be invoked time after time

again by a wide variety of social groups to defend and legitimise national hydraulic programmes and the policy of land

reform through 'internal colonial' settlements. The regeneracionist project became formulated as a 'hydrological correction

of the national geographical problem' (Gómez Mendoza, 1992). For Costa, hydraulic politics sublimated the totality of the

nation's economic programme, not only for agriculture, but for the totality of Spanish socio-economic life. Moreover,

several participants in the debate regarded hydraulic constructions for irrigation purposes as a progressive alternative to the

traditional policy of tariffs and import restrictions, supported by dryland latifindustas (Torres Campos, 1907).

In short, the hydraulic basis of 'el regeneracionismo' and the cause for the 'misfortunes of Spain' resided in the uneven

distribution of rainfall, the torrential and intermittent nature of its fluvial system, making Spain 'the anti-chamber of Africa'

(de Reparez, 1906). Therefore, the great modernising drive of the revivalists demanded not only an imitation and use of

nature, but "to create it, to increase the amount of fertile soil by making a hydraulic artery system cross the whole country - a national network of dams and irrigation channels" (Gómez Mendoza and Ortega Cantero, 1992: 174) (my emphasis).

According to Alfonso Orti (1984:12), the symbolic power of this material intervention for the production of a new

hydraulic geography to achieve 'hydraulic regenaration' of the country constituted 'a mythical power, a collective illusion

and the imagined reconciliation of diverse ideologies' and served the productionist logic of the new liberal bourgeoisie

which aspired to transform society and space to function according to the principles of capitalist profitability and

integration into a European modernising project.

3.4. Humming to nature's tune: the generation of '98.

This hydraulic regeneracionism coincided with an intellectual and professional 'critical' regeneracionism, symbolised by the

literary 'generacion de 98', which rediscovered, both aesthetically and sociologically, the underdeveloped regions of arid

Spain, whose only perspective for future emancipation resided in embracing hydraulic politics. The fate of the drylands

became the symbol of the decline and failure of Spain to modernise. The 'hydraulic desire' of the arid lands became the

'leitmotiv' of much of the regeneracionist literature at the time. In the novel "La Tierra de Campos" (1896), Ricardo Macias

Picavea describes the 'hydraulic' fate of the drylands as follows :

"Autumn had passed without a drop of water, to the point that the seeds had dried out. The winter rains did not come either.

The north-eastern winds, dry and icy, haven't stayed away a single day. And what a period of frost! Black, scorching,

without a drop of water in the atmosphere, with temperatures of twelve and fifteen degrees below zero" (p. 151) (cited in

Orti, 1984: 17).

And, of course, only a hydraulic quest can revive the land as the hydraulic hero of the novel maintains :

"without the prior solution of the vital problem of irrigation, no significant reforms will be possible in this country" (p.

151).

Of course, the symbolic and mythological powers of water are mobilised here as the basis for the hydraulic revival of the

country. Contact with water always holds the promise of regeneration, of a new birth, while immersion in water fertilises

and strengthens the powers of life. Against the dryness of the land -- freezing, barren, grey and uncivilised -- which

represents the misery and the frustration of underdevelopment, stands the abundance of water which puts the hydraulic

utopia of the regenerationist discourse at the centre of the promise of a revival of the vital energies of the country and of an

abundant paradise. In "El Problema Nacional", the same Macia Picavea summarises the hydraulic mission as the only

option and necessary strategy for national development :

"There are countries which ... can solely and exclusively become civilised with such a hydraulic policy, planned and

developed by means of designated grand works. Spain is among them .... And the truth is that Spanish civilised agriculture

finds itself strongly subjected to this inexorable dilemma: to have water or to die ... Therefore, a hydraulic politics imposes

itself; this requires changing all the national forces in the direction of this gigantic enterprise ... We have to dare to restore

great lakes, create real interior seas of sweet water, multiply vast marshes, erect many great dams, and mine, exploit and

withhold the drops of water that fall over the peninsula without returning, if possible, a single drop to the sea" (p. 318-320).

This patriotic mission which requires the convergence of all national forces fuses around the hydraulic programme which

becomes the embodiment and representation of a collective myth of national development. This project is sustained and

inspired by a reformist geographical optimism which must substitute for the social and political pessimism of Spain's turnof-the-century condition (Orti, 1984: 18). The hydraulic utopia of abundant waters for all would not only produce an

'ecological harmony', but also contribute to the formation a socially harmonious order. The production of a new hydraulic

geography would reconcile the ever growing social tensions on the Spanish countryside; tensions which were taking acute

class forms and resulted from the adverse and conflictuous conditions of scarcity and inequality. The hydraulic 'heroes' of

the 1890s novelists (as well as the water engineers -- see below) were those apostolic figures whose voluntarist vision

fought against the desperation and ignorance of the rural masses and the persistent dominance of the traditional rural elites

and impose on all their modernising programme hydraulic revival as the only means to resolve the contradictions emerging

from the 'Social Question' that seemed to plague Spain after its imperial downfall (Orti, 1984: 19). This romantic and

autocratic personality of the water missionary becomes a literary hero in some of the period's regeneracionist novels. César

Moncado in the novel of failed revivalism ("César o nada") by Pío Baroja written in 1909-1910 is an arch-typical example

of such hydraulic missionary. The hero, a agricultural and hydraulic regeneracionist, is determined to create a municipal

democracy in a Castillian village "Castro Duro", using his personal power to redistribute land and promote a plan for

irrigation and reforestation (Baroja, 1909-1910). However the hero fails in his aspirations to defeat the landed aristocracy

and its allies and the novelist narrates the final victory of 'arid', conservative and counterrevolutionary rural Spain :

"Today, Castro Duro [the village of the hero]has now definitively abandoned its pretensions to live ... The springs have

dried up, the school has closed, the trees ... were pulled up. The people emigrate, but Castro Duro will continue living with

its venerated traditions and its sacrosanct principles .... sleeping under the sun, in the middle of its fields without irrigation"

(p. 379).

The novel contemplates the faith of the land if the revivalist mission does not succeed while already foreshadowing the

obstacles and the almost unavoidable failure of the project. The desperation, the emphasis on the role of the enlightened

leader who pursues his (sic!) mission and the stubborn resistance of traditional forces already hint at and pave the way for

the later emergence of the falangist ideology and fascist victory.

3.5. The State as Master Socio-Environmental Engineer.

"To irrigate is to govern" (J. Costa)

Surely, such an ambitious perspective to revive (regenerate) Spain through a geographical project necessitated concerted

action and collective control. The regeneracionists welcomed the liberation of international markets and the demise of 19th

century protectionism under which the dryland latifundistas of (mainly southern) Spain flourished. Of course, trade

liberalisation had subsequently plunged them into a deep crisis in the aftermath of the expansion of the US wheat export

boom. The traditional landed bourgeoisie was economically weakened as a result of this, but their political commitment to

maintain their power position did not abate.

Nevertheless, central State intervention to produce a nature amenable to the requirements of a modernised competitive and

irrigated agriculture was considered to be essential (Ortéga, 1975). The State needed to intervene directly in the

implementation of hydraulic works which would permit to 'remake the geography of the fatherland', to revive the national

economy and 'to regenerate the people' (la raza). The hydraulic politics were for Costa (1975) a way to insert Spain within a

European socio-spatial framework after its loss of influence in the Americas on the basis of a rural development vision that

combined a Rousseauan ideal with a small-scaled, independent and democratic peasant society. The promotion of the rural

ideal on the basis of a petty bourgeois ideology would become the spinal cord of the liberal state and the route to the

'Europeanisation' of the nation (Nadal Reimat, 1981: 139; Fernández Clemente, 1990).

The growing demand for water and the requirements for a more efficient and equitable distribution of irrigation waters

necessitated a fundamental change in the legal status and appropriation rights of water. The liberal revolution in Spain

(approximately 1811 - 1873), which had attempted an institutional (anti-)feudal restructuring to promote capitalist forms of

ownership and circulation of goods as commodities, extended also to what Maluquer de Motes (1983) called the

'depatrimonialisation of water'. Indeed, as with land, water did not have the characteristic of a privately owned and tradable

good. The existence of seigniorial rights over water prevented or blocked the development of productive activities which

necessitated ever larger quantities of water. Although the depatrimonialization of land and of water reinforced their private

character, the growing political and economic crisis of liberalism towards the end of the century prevented embarking on a

productivist and privately run programme to maximise production 'to the last drop of water'. The regeneracionist vision,

then, faced with the failure of privatised and commodified water to operate as an efficient allocative and productive

instrument, promoted the emergence of a collective spirit ('illusion' in the words of Alfonso Orti (1984: 14)). The latter

implied that the supply of the necessary quantities of water was only possible under a public and socialised form or, in other

words, through the state. This collective and State-led, but productivist and modernising vision, would eventually also

include the State-led production of 'great hydraulic works' (Ortega, 1975). In sum, the regeneracionists turned to the State -after the failure of the Liberal project to defeat the feudal elites -- as the agent that could generate a sufficiently large

volume of capital to 'mobilise the natural resources'. Moreover, for Costa, the productivist modernisation by means of the

hydraulic motor would in fact consolidate the Liberal State in Spain (Orti, 1984: 85). In short, a free-market based,

intensive and productive national economy, whose accumulation process would accelerate on a par with other 'northern'

European states, necessitated a transformation in the State (but not of the State) in a double and deeply contradictory sense.

First, power relations within the State apparatus needed to change in favour of a more modernist alliance of petty-owners,

industrialists and modernising engineers and, secondly, the social reform that such a revolution required needed to be

supported by the State as well by taking a leading role in the grand hydraulic works that would lay the foundations for a

modernising Spain. Surely, this contradiction turned out to be irreconcilable via non-revolutionary forms of alliance

formation. These two tasks were of course mutually dependent and still strong traditional forces kept control over key State

functions. Once again, the mosaic of contradictory forces and the resistance of the traditionalists would stall the State-led

modernising efforts, resulting in more acute and openly fought social antagonisms. These would eventually pave the way

for dictatorial regimes from the 1920s onwards.

Despite the collectivist discourse of much of the regeneracionist literature, it remained deeply committed to a project of

insertion into an international capitalist market. Although the State needed to take central control over water and forests, it

should do so on the basis of a land ownership structure that was essentially private and market-led (see also Fernández

Clemente, 1990). The hydraulic agenda that Costa and his colleagues advocated as the basis for regenerating Spain was

clouded with revolutionary claims, but defended basically a reformist route for development against the stronghold of an

anti-reformist, economically and culturally conservative and protectionist elite. In sum, two models of capitalist

accumulation, with evidently different supporting social groups and allies, crystallised around the hydraulic debates at the

time. Of course, the social, political and ecological consequences and implications of these two models would differ

fundamentally (although they both shared a basically organicist vision of the world). The issue of land ownership and the

role of water therein revolved around the question of who would own and control what part of the land and its waters. For

the regeneracionist, for whom petty ownership constituted the way ahead, the hydraulic route was an essential precondition,

while the limited possibilities for accumulation pointed at the State as the only body that could generate the required

investment funds on the one hand and push through the necessary reforms in the face of strong and sustained opposition

from the landed aristocracy on the other (Ortéga, 1979). At the same time, the very support of at least some sections of the

old elites could be secured via this reformist route, which did not threaten their fundamental rights as landowners and

defended 'rural' power against the rising tide of the urban industrial elites and proletariat. This was indeed quite central to

forge the support of the dominant catholic groups which defended a solidaristic and organic model of social cohesion.

3. 6. Purification and the transformation of nature: Hydraulic Engineers as Producers of Socio-Nature.

The hydraulic intervention to create a waterscape supportive of the modernising desires of the revivalists without

questioning the social and political foundations of the existing class structure and social order was very much based on a

respect for the 'natural' laws and conditions. The latter were assumed to be or thought of as intrinsically stable, balanced,

equitable and harmonious. The hydraulic engineering mission consisted primarily in 'restoring' the 'perturbed' equilibrium

of the erratic hydrological cycles in Spain. Of course, this endeavour required a significant scientific and engineering

enterprise, firstly in terms of understanding and analysing nature's 'laws' and, secondly, to use these insights to work

towards a restoration of the 'innate' harmonious development of nature and nature's geography. The moral, economic and

cultural 'disorder' and 'imbalances' of the country at the time paralleled the 'disorder' in Spain's erratic hydraulic geography,

both of whom needed to be restored and re-balanced (as nature's innate laws suggested) to produce a socially harmonious

development. Two threads can and have to be woven together in this context. On the one hand the pivotal position of a

particular group of scientists in the hydraulic arena, i.e. the Corps of engineers and -- but not unrelated -- the changing

visions concerning the scientific management of the terrestrial part of the hydrological cycle on the other. Both, in turn,

were of course linked to the rising prominence of hydraulic issues on the socio-political agenda at the turn of the century.

The Engineering Corps, founded in 1799, was (and still is) the professional collective responsible for the development and

implementation of public works. The Corps of Engineers is a highly elitist, intellectualist, 'high-cultured', male-dominated,

socially homogeneous and exclusive organisation that has over the centuries taken a leading role in Spanish politics and

development (Mateu Bellés, 1995). The decision-making structure is highly hierarchical and all key managerial and

organisational bodies, such as the 'Junta Consultiva de las Obras Publicas', the Hydrological Divisions, Provincial

Headquarters and ad hoc study commissions, are exclusively manned (sic!) by engineers. In line with the emergent

scientific discourse on orography and river basin structure and dynamics, the engineering community argued for the

foundation of engineering and managerial intervention on the basis of the 'natural' integrated water flow of a water basin

rather than on the basis of historically and socially formed administrative regions. The emergent geographical 'tradition' had

indeed questioned the 'traditional' political-administrative divisions of the country and argued for a re-ordering of the

territory on the basis of the country's orographical structure. The latter, in turn, needed to be the planning unit for hydraulic

interventions. This 'scientific' perspective is succinctly summarised by Cano García (1992: 312) :

"To revert to the great orographical delimitation for organising the division of the land represents a contribution made from

within the strict field of our discipline and at the same time, at least initially, it shows the abandoning of traditional]

political divisions and the importance of other perspectives and concepts" (my translation).

This 'scientific' natural division provides an apparently enduring and universal scale for territorial organisation in lieu of the

more recent, political and historical scales associated with politico-administrative boundaries. As Smith (1969:20) argues,

'... the identity of the drainage basin seemed to offer a concrete and "natural" unit which could profitably replace political

units as the areal context for geographical study'. Brunhes' (1920) insistence on the water basin as the foundation for the

organisation of the land as 'water is the sovereign wealth of the state and its people (p. 93)' (see also Chorley, 1969) was

widely used in Spain and its arguments rallied in defence of a new orographic-administrative organisation of the territory.

The history of the delimitation of Hydrological Divisions is infused with the influence of the regeneracionst discourse on

the one hand and the 'scientific' insights gained from hydrology and orography on the other. The attempt to 'naturalise'

political territorial organisation was part and parcel of a strategy of the modernisers to challenge existing social and

political power geometries. The complex history of the formation of 'river basin authorities' and their articulation with other

'political' forms of territorial organisation, in particular the national state, is a long, complicated and tortuous one. 'Nature'

would becomes inextricably connected to the choreography of power and the scientific discourse on nature is strategically

marshalled to serve power struggles for the control over and management of water. The river basins would become the

scale par excellence through which the modernisers tried to undermine or erode the powers of the more traditional

provincial or national state bodies. Therefore, the struggle over the territorial organisation of intervention expresses the

political power struggles between traditionalists and reformers. While the 'river basin' defenders would become the

founding 'fathers' of the regeneracionist agenda, the traditional elites held to the existing territorial structure of power. The

regeneracionist engineers incorporated the 'naturalised' river basins into their political project. Capturing the scale of the

river basin and transforming it into their base for political, socio-economic and technical interventions was one of the

central arenas through which the power of the traditionalists (and the scales over which they exercised hegemonic control)

was challenged. In fact, this re-scaling of the state and the articulation of different scales of governance became one the

great arenas of struggle for control and power. For the engineering community and the modernisers, the scale of the river

basin, which the scientific discourse had offered as a 'natural' foundational unit of the physical world and, by implication, a

desirable scale for management and control, became the battleground over which political and social conflict was fought.

The modernisers took hold of the hydrological divisions and tried to develop them as their power basis for instigating the

hydrological revolution they thought to be essential for Spain's future, while the national scale remained more firmly in the

hands of the traditional elites. The bumpy history of the hydrological divisions records this struggle. The instability of their

administrative and political organisation reflects the relative power of the traditional power brokers. It will take until the

France revolution before this issue is solved when the hydrological dream and its intellectual bearers (the engineers) was

aligned with and incorporated in a new and more organicist structure of the state.

This negotiation of scale and the science/politics debate around the scaling of hydraulic intervention and planning raged for

almost century before the current structure was put into place (Cano Carcía, 1992; Mateu Bellés, 1995). The first

Hydrological Divisions (10 in total) were established by Royal Decree in 1865 and, from the very beginning, were

considered to be major instruments for the economic modernization process. Some of these ten Divisions more or less

coincided with major river basins (Ebro, Tago, Duero), others (like in the South) had a much closer correspondence to

provincial boundaries. All were named after the provincial capital city where the head-office was located. Their basic merit

was to serve as an institutional basis responsible for the collection of statistical data to assist the study and research of the

water cycle. These surveys could then be used as inputs to the real power holders (provincial head offices for public works,

special ad hoc commissions or private industry). This early attempt to set up Hydrological Divisions came to an end in

1870 when they were abolished. They were partly re-erected in 1870, reduced to seven and abolished again in 1899. Only

in 1900, in the wake of the regeracionist spirit, the seven Hydraulic Divisions were re-established and their tasks extended

to include the detailed study and planning of, and the formulation of proposals for hydraulic interventions. However, the

final powers would stay with the Provincial level which supervised and executed the hydraulic works and, of course, with

the central State for financing, control and decision-making. It is only from 1926 onwards that the current Confederaciones

Sindicales Hydrográficas were gradually established. The last of these ten Confederaciones was only finally established in

1961! (see Figure 2). It is also from that moment onwards that their names reflected the river basins for which they were

responsible rather that the previous political-territorial naming. In addition, they acquired a certain political status with

participation from the State, Banks, Chambers of Commerce, Provincial authorities, etc.... At each stage the engineers took

the lead roles and became the 'activists' of the regeneracionist project through the combination of their legitimisation of the

beholders of 'scientific' knowledge and insights with their privileged position as a political elite Corps within the state

apparatus. The turbulent history and the early failure to set up effective river basin authorities reflect the failure of the early

modernisers to fundamentally challenge existing and traditional power lineages and scales. It is only from the later 1920s

and, in particular during the Franco era, that the 'regeneracionist' project will be gradually implemented.

Insert Figure 2 about here

4. CONCLUSIONS.

In sum, the 'regeneracionist' agenda(s) firstly maintained that the restoration of wealth in Spain should be based on the

knowledge of the laws and balances of nature; secondly, this restoration required the correction of defects imposed by the

geography of the country and particularly its 'imbalances in its climatic and hydraulic regimes'; and thirdly, this enterprise

of geographical rectification could, because of its range and importance, only be carried out by the central public authorities

(Gómez Mendoza and Ortega Cantero, 1992: 173). The hydraulic mission was seen as the 'solution' to the social question.

Failing this, social tensions were bound to intensify and struggle, if not civil war, would be the likely outcome. Ironically,

of course, the voluntarist, powerful and autocratic hydraulic engineer pursuing a voluntarist programme of imposed reform

foreshadowed the falangist ideology of the later Franco years. The failure of the hydraulic politics in the early decades of

the twentieth century announced what Costa and his literary allies had feared and desperately tried to prevent. At the same

time, the centralising fascist regime could finally push through the production of a new geography, a new nature and a new

waterscape, something the reformist regeneracionists of the turn of the century had so dismally failed to accomplish. This

quasi-object and hybrid thing that, until this very day, embodies Spain's modernisation process expresses how modernity is

deeply and inevitably a geographical project in which the intertwined transformation of nature and society are both medium

and expressive of shifting power positions that become materialised in the production of new water flows.

It is the maelstrom of tensions and contradictions that weave the above material, discursive, ideological and

representational together in often perplexing, always deeply heterogeneous, collages of changing and shifting positions of

power and of struggle that shaped the production of the Spanish waterscape over the next century in decisive ways.

Table 1. Evolution of Dam Construction in Spain.

River Basin Period

Before 1900 1901-1935 1936-1970 1971-1986 After 1986 86 TOTAL

North 1 10 89 36 7 143

Duero 0 8 45 11 8 72

Tajo 27 8 74 75 17 201

Guadiana 14 13 24 40 13 98

Guadalquivir 0 13 41 32 16 102

Sur 2 6 2 15 0 25

Segura 3 5 8 8 1 25

Jucar 5 8 25 4 3 45

Ebro 6 52 86 24 5 173

TOTAL

58 123 394 235 70 884

Note: Table excludes 'Islas Canarias'. For the location of each basin in Spain, see Figure 2.

Source: Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo (1990) Plan Hidrólogico -- Síntesis de la Documentación Básica,

Dirección General de Obras Hidraulicas, Madrid, pp. 32-33.

Figure1. Hybridisation: The Production of Socio-Nature

Figure 2. Spains' Political and Hydraulic Geography

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the European Union's Fourth Framework Training and Mobility Programme for the

financial assistance to carry out this research. I am particularly grateful to the Department of Geography of the University

of Seville for hosting during the summer and fall of 1996, to Dr. Leandro del Moral for sharing his expertise, material,

thoughts and friendship and to Prof. Imaculada Caravaca for her hospitality and interest. I would like to thank Leandro del

Moral, Maria Kaika, Judith Gerber, Karen Bakker, Ben Page, Guy Baeten and Josep-Antoni Gar° for their comments on

earlier drafts of this paper and for providing a stimulating environment for discussion, intellectual debate and support. The

responsibility for the final product remains entirely mine.

Bibliography

Altamira R. (1923) Ideario Pedagógico, Editorial Reus, Madrid.

Balibar E. (1995) The Philosophy of Marx, Verso, London.

Baroja P. (1909-1910(1965)) César o Nada, Editorial Planeta, Barcelona.

Benton T. (1989) "Marxism and Natural Limits: An Ecological Critique and Reconstruction", New Left Review, 178, pp.

51-86

Benton T. (Ed.) (1996) The Greening of Marxism, Guilford Press, New York.

Berman M. (1983) Everything that is Solid Melts into Air -- The Experience of Modernity, Verso, London.

Brunhes J. (1920) Geographie Humaine de la France, Hanotaux, Paris.

Cano García G. (1992) "Confederaciones Hidrográficas", in Gil Olcina A., Morales Gil A. (Eds.) Hitos Históricos de los

Regadíos Españoles, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Madrid, pp. 309-334.

Castree N. (1995) "The Nature of Produced Nature: Materiality and Knowledge Construction in Marxism", Antipode,

27(1), pp. 12-48.

Chorley R.J. (1969) "The Drainage Basin as the Fundamental Geographic Unit", in Chroley R.J. (Ed.) Introduction to

Physical Hydrology, Methuen, London, pp. 37-59.

Costa J. (1900 (1981)) Reconstitución y Europeización de España, Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local, Madrid.

Costa J. (1975 (1892)) Política Hidráulica (Misión Social de los Riegos en España), Edición de la Gaya Ciencia, Madrid.

del Moral Ituarte L. (1996) "Sequía y Crisis de Sostenibilidad del Modelo de Gestión Hidráulica", in Marzol M.V., Dorta

P., Valladares P. (Eds.) Clima y Agua -- La Gestión de un Recurso Climático, La Laguna, pp. 179-187.

Demeritt D. (1994) "The Nature of Metaphors in Cultural Geography and Environmental History", Progress in Human

Geography, 18: 163-185.

de Reparez G. (1906) "Hidráulica y Dasonomiá", Diario de Barcelona, 21 de Julio de 1906.

Fernández Almaro M. (1970) Historia Política de la España Contemporánea Vol. 3, 1897-1902, Alianza Editorial, Madrid

(2nd Edition).

Fernández Almaro M. (1970) Historia Política de la España Contemporánea Vol. 3, 1897-1902, Alianza Editorial, Madrid

(2nd Edition).

Fernández Clemente E. (1990) "La Política Hidráulica de Joaquín Costa", in Pérez Picazo T., Lemeunier G. 5Eds.) Agua y

Modo de Producción, Editorial Crítica, Barcelona, pp. 69-97.

Fontana J. (1975) Cambio Económico y Actitudes Políticas en la España del Siglo XIX, Editorial Ariel, Barcelona.

Garrabou R. (1975) "La Crisi Agrária Espanyola de Finals del Segle XIX: Una Etapa del Desenvolupament del

Capitalisme", Recerques, 5, 163-216.

Gerber J. (1997) "Beyond Dualism -- The Social Construction of Nature and the Natural and Social Construction of Human

Beings", Progress in Human Geography, 21, 1-17.

Giddens A. (1990) Consequences of Modernity, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Gómez Mendoza J. (1992) "Regeneracionismo y Regadíos", in Gil Olcina A., Morales Gil A. (Eds.) Hitos Históricos de los

Regadíos Españoles, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Madrid, pp. 231-262.

Gómez Mendoza J., Ortega Cantero N. (1987) 'Geografía y Regeneracionismo en España', Sistema, 77, pp. 77-89.

Gómez Mendoza J., Ortega Cantero N. (1992) "Interplay of State and Local Concern in the Management of Natural

Resources: Hydraulics and Forestry in Spain (1855-1936)", GeoJournal, 26(2): 173-179.

Gómez Mendoza J., del Moral Ituarte L. (1995) "El Plan Hidrológico Nacional: Criterios y Directrices", in Gil Olicna A.,

Morales Gil A. (Eds.) Planificación Hidráulica en España, Fundación Caja del Mediterráneo, Murcia, pp. 331-398.

Grundman R. (1991) Marxism and Ecology, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Haraway D. (1991) Simians, Cyborgs and Women - The Reinvention of Nature, Free Association Books, London.

Haraway D. (1997) Modest-Witness&Second-Millennium.FemaleMan©-Meets_ (&=@) OncoMouseTM, Routledge,

London.

Harvey D. (1989) The Condition of Postmodernity, Blackwell, Oxford.

Harvey D. (1996) Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference, Blackwell, Oxford.

Isern D. (1899) El Desastre Nacional y sus Causas, Imprenta de la Viuda de Minuesa de los Ríos, Madrid.

Latour B. (1993) We Have Never Been Modern, Harvester Wheatsheaf, London.

Lefebvre H. (1991) The Production of Space, Blackwell, Oxford.

Lefebvre H. (1995) Introduction to Modernity, Verso, London.

Levins R., Lewontin R. (1985) The Dialectical Biologist, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mas.

Lewontin R. (1993) The Doctrine of DNA: Biology as Ideology, Penguin, Harmondsworth

Lewontin R. (1997) "Genes, Environment, and Organisms", in Silvers R.B. (Ed.) Hidden Histories of Science, Granta

Books, London, pp. 115-139.

Macías Picavea R. (1895) Geografía Elemental. Compendio didáctico y razonado, Establecimiento tipográfico de H. de J.

Pastor, Valladolid.

Macías Picavea R. (1896) La Tierra de Campos, Librería de Victoriano Suárez, Madrid.

Macías Picavea R. (1899 (1977)) El Problema Nacional, Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local, Madrid

Mallada L. (1890 (1969)) Los Males de la Patria y la futura Revolución Española, Alianza Editorial, Madrid

Maluquer de Motes J. (1983) "La Despatrimonialización del agua: movilización de un Recurso Natural Fundamental",

Revista de Historia Económica, 1(2), 76-96.

Mateu Bellés (1995) "Planificación Hidráulica de las Divisiones Hidrológicas", in Planificación Hidráulica en España,

Fundación Caja del Mediterráneo, Murcia, pp. 169-106.

Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo (1990) Plan Hidrólogico -- Síntesis de la Documentación Básica, Dirección

General de Obras Hidraulicas, Madrid.

Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Transportes (1993) Plan Hidrólogico Nacional -- Memoria, Madrid.

N. (1930) "Editorial", Montes e Industrias, 1(2), 29-30.

Nadal Reimat E. (1981) "El Regadío durante la Restauración", Revista Agricultura y Sociedad, 19: 129-163.

Olman B. (1993) Dialectical Investigations, Routledge, London.

Ortega Cantero N. (1995) "El Plan General de Canales de Riego y Pantanos de 1902", in Gil Olicna A., Morales Gil A.

(Eds.) Planificación Hidráulica en España, Fundación Caja del Mediterráneo, Murcia, pp. 107-136.

Ortega N. (1975) Política Agraria y Dominación del Espacio, Editorial Ayuso, Madrid.

Ortí A. (1976) "Infortunio de Costa y Ambigüedad del Costismo: una reedición acrítica de 'Política Hidráulica'",

Agricultura y Sociedad, 1: 179-190.

Ortí A. (1984) "Política Hidráulica y Cuestión Social: Orígenes, etapas y significados del regeneracionismo hidráulico de

Joaquín Costa", Revista Agricultura y Sociedad, 32: 11-107.

Ortí N. (1994) "Política Hidráulica y Emancipación Campesina en el Discurso Político del Populismo Rural Español (entre

las dos Repúblicas contemporáneas)", in Romero J., Giménez C. (Eds;) Regadíos y Estructuras de Poder, Ed. Instituto de

Cultura "Juan Gil-Albert', Diputación de Alicante, Alicante, pp. 241-267.

Pérez De La Dehesa R. (1966) El Pensamiento de Costa y su Influencia en el 98, Ed. Sociedad de Estudios y Publicaciones,

Madrid.

Reguerra Rodríguez A. (1986) Transformación del Espacio y Política de Colonización, Secretario de Publicaciones,

Universidad de León.

Rodríguez de la Rua J. (1993) "Evolución y Tendencia de la Política Hidráulica", Revista de Obras Públicas, Vol. 140, Nr.

3320, pp. 7-17.

Ruiz J. M. (1993) "La Situación de los Recursos Hídricos en España. 1992", in Brown L.R. (Ed.) La Situación en el Mundo

- 1993, Ediciones Apóstrofe S.L., Madrid, pp. 385-450.

Schmidt A. (1971) The Concept of Nature in Marx, New Left Books, London.

Smith N. (1984) Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space, Blackwell, Oxford.

Smith N. (1996) "The Production of Nature", in Robertson G., Mash M., Tickner L., Bird J., Curtis B., Putnam T. (Eds.)

FutureNatural -- Nature/Science/Culture, Routledge, London, pp. 35-54.

Smith T.C. (1969) "The Drainage Basin as an Historical Unit for Human Activity", in Chorley R.J. (Ed.) Introduction to

Geographical Hydrology, Methuen, London, pp. 20-29.

Swyngedouw E. (1996) "The City as a Hybrid -- On Nature, Society and Cyborg Urbanisation", Capitalism, Nature,

Socialism, Vol. 7(1), Issue 25 (March), pp. 65-80.

Swyngedouw E. (1996) Water and the Politics of Economic Development in Southern Spain, Final Report, DG XII,

Commission of the European Communities, Brussels 34 pp. (copy available from author)

Torres Campos R. (1907) "Nuestros Ríos", Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Madrid, XXXVII, 7-32.

Tuñón De Lara M. (1971) Medio Siglo de Cultura Española (1885-1936), Editorial Tecnos, 2.a edición, Madrid.