an overiview of clinical documentation for the chiropractic

advertisement

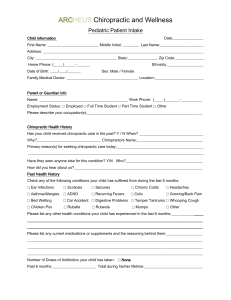

AN OVERIVIEW OF CLINICAL DOCUMENTATION FOR THE CHIROPRACTIC PROFESSION Steven G. Yeomans, DC, FACO 404 Eureka Street Ripon, WI 64971-0263 920-748-3644 (Ph) 920-748-3642 (Fax) s@yeomansdc.com Course Objective: TO BULLET-PROOF YOUR DOCUMENTATION AGAINST AN ADVERSARIAL REVIEW PROCESS Table of Contents Content ACA Recommendations (2001) Page # 3-4 WCA Recommendations (1996) Intro & Acknowledgements ………………………………………………... 5-8 Chapter 1: Documentation recommendations ………………………….….. 9-18 Chapter 2: Commonly used mechanisms of record keeping ……….……… 19-21 Chapter 3: Commonly used outcome assessment measurements …………. 22-24 Chapter 4: A primer on chiropractic listings ……………………….……… 25-26 Chapter 5: Glossary ……………………………………………………….. 27-28 Chapter 6: Commonly used abbreviations ………………………….……… 29-32 Appendix A: HCFA Guidelines for Patient History Level Selection ……… 33 Appendix B: Bibliography ………………………………………………… 34-35 Chart Audit 36 Yellow Flags (psychometrics) 37-38 CPT Codes 39-40 Bibliography 41-44 2 Ref: ACA Today, March 2001 The Newsletter of the American Chiropractic Association CLINICAL DOCUMENTATION KEY TO REIMBURSEMENT FOR CHIROPRACTIC CLAIMS ARLINGTON, VA – During its recent meeting, the American Chiropractic Association (ACA) House of Delegates passed a resolution to assist doctors of chiropractic in successfully being reimbursed for necessary patient care by insurance companies. ACA is now committed to disseminating the recommendations contained in the resolution to doctors of chiropractic, chiropractic organizations and chiropractic colleges nationwide. Last year, representatives from 13 of the largest insurers in the United States met with ACA representatives during the second meeting of the ACA-sponsored Claim Solutions Work Group. Based on the suggestions made during this meeting and on recent trends, ACA recommends certain basic requirements be considered as appropriate clinical documentation in patient record keeping. Some of the insurers present at the meeting agreed that using these practices will also reduce clinical record requests by 50 percent. “The mutual goal of the insurers and doctors of chiropractic at this meeting was to simplify the claims process,” explained Pat Jackson, vice president of professional development for ACA. “This way, chiropractors can reduce administrative costs and get paid for more covered claims, and insurers can reduce claims expenses.” According to Ms. Jackson, many insurers are already adopting the recommended guidelines resulting from the meeting in order to educate their claim personnel on appropriate requests for chiropractic clinical documentation. The ACA also contends that a concerted effort by the chiropractic profession to standardize clinical documentation will improve reimbursement experience exponentially for doctors of chiropractic. For this reason, a special effort will be made to share this information with chiropractic colleges so it can be incorporated into the curricula. ACA recommends the following documentation procedures: 1. The nationally accepted HCFA billing 1500 form must be completed in detail. This means all required fields must be completed. 2. Subjective, objective, and treatment (if rendered) components should be incorporated into patient records on each visit. A customized format is not needed but these elements must exist consistently. Any significant changes in the clinical picture (e.g. significant patient improvement or regression) should be noted. 3 3. All ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and CPT treatment and procedure codes must be validated in the patient chart and coordinated as to the diagnoses and treatment code descriptors. 4. Uniform chiropractic language should be used within the profession for describing care and treatment. Non-standard abbreviations and indexes should be defined. 5. Documentation for the initial (new patient) visit, new injury or exacerbation should consist of the history and physical and the anticipated patient treatment plan. The initial treatment plan, except in chronic cases, should not extend beyond a 30-45 day interval. Subsequent patient visits should include significant patient improvement or regression if demonstrated by the patient on each visit. As the patient progresses, the treatment plan needs to be reevaluated and appropriately modified by the treating doctor of chiropractic (chiropractic physician) until the patient can be released from care, if appropriate. 6. If the patient is disabled, a statement(s) on the extent of disability and activity restriction is needed at initial and subsequent visits as appropriate over the course of care. 7. Records can be attached to each billing to pre-empt requests; however, it is not mandatory. Local insurers should be contacted for preferences (i.e., No fault PIP insurers may require records every visit while health insurers may not). 8. All records must be legible and understandable, released within the authority given by the patients, in a secure, confidential manner and in compliance with existing state (or federal) statutes. 9. The patient name and initials of the person making the chart notation (especially in multi-practitioner offices) should appear on each page of the medical record. 10. If the above recommendations have been met, then the answers as to why the necessity for continuing treatment are answered. 11. The insurance industry must improve their claim adjusting procedure by using chiropractic consultants. The ACA can use its resources to assist in this initiative. Contact the American Chiropractic Association Office of Professional Development by phone at (800) 986-4636, ext. 222, or by e-mail at pjackson@amerchiro.org for more information. ### 4 Wisconsin Chiropractic Association Recommendations for Chiropractic Documentation (1996) Wisconsin Chiropractic Association Recommendations for Chiropractic Documentation 5 General Disclaimer This document contains recommendations for the clinical documentation of chiropractic care. These recommendations are intended for educational and instructional purposes only and do not constitute a standard of care for any specific clinical situation. These recommendations, which may need to be updated, are intended to be flexible. In is not the purpose of this document, which is advisory in nature, to take precedence over any federal, state or local statute, rule, regulation or ordinance which may affect chiropractic practice. This document may provide some assistance to third parties in the evaluation of chiropractic care, but it is not by itself a proper basis for evaluation. Many factors must be considered in determining clinical or medical necessity. Methods of chiropractic documentation must be sufficiently flexible to allow for variations in practice methods, as well as differing complexities of individual cases. Further, these recommendations will require constant re-evaluation as additional scientific and clinical information becomes available. 6 Wisconsin Chiropractic Association Recommendations for Chiropractic Documentation Table of Contents: Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1: Documentation recommendations ……………………………… 8-17 Format Legibility Patient consent Initial entry: Subjective Initial entry: Objective Initial entry: Assessment Initial entry: Treatment plan Daily notes Progress notes X-ray reports Chapter 2: Commonly used mechanisms of record keeping ……………… 18-20 Chapter 3: Commonly used outcome assessment measurements …………. 21-23 Chapter 4: A primer on chiropractic listings ………………………….…… 24-25 Chapter 5: Glossary ……………………………………………………….. 26-27 Chapter 6: Commonly used abbreviations ………………………………… 28-31 Appendix A: HCFA Guidelines for Patient History Level Selection ……… 32 Appendix B: Bibliography ………………………………………………… 33-34 Acknowledgments: The Wisconsin Chiropractic Association is indebted to chiropractic colleges and insurers who provided valuable background information for the work of the Committee, and also to the Committee members for their diligent effort on this project. 7 Introduction: Over the past decade, chiropractic has occupied a constantly growing position in today’s complex health care delivery system. Chiropractors in Wisconsin now work routinely with a myriad of parties who are interested in assessing the quality of clinical work performed by the chiropractor. The principal method through which other parties attempt to assess the quality and necessity of a chiropractor’s work is through submitted clinical documentation. The clinical records of Wisconsin chiropractors are now examined with an increased amount of scrutiny. Many different payors and agencies have the right to access a chiropractor’s clinical records, including: insurers who wish to determine whether a claim is a covered benefit under the terms of their contract with the patient managed care organizations who conduct reviews of clinical record keeping as part of their quality assurance and utilization review programs attorneys who utilize clinical documentation as evidence in personal injury litigation attorneys who represent patients in malpractice suits against chiropractors other health care providers who may request records in order to coordinate interprofessional patient care other chiropractors who assist with treatment for a patient state regulatory agencies, who investigate consumer complaints, review payment for government programs, etc. Methods of chiropractic documentation must be sufficiently flexible to allow for variations in practice methods, as well as differing complexities of individual cases. Because chiropractic practice patterns vary from medical practice patterns, recommendations for chiropractic documentation necessitate additional modifications when compared to generally accepted medical record keeping formats. 8 Chapter 1: Wisconsin Chiropractic Association Recommendations for Clinical Documentation 1. General information: The purpose of these recommendations are: A. to serve as an informational source to doctors. These recommendations represent well-accepted, contemporary views on documentation issues as reported in the biomedical literature. Some of the source materials include: Health Care Financing Administration documentation guidelines Record keeping standards for the National Committee on Quality Assurance. chiropractic and medical textbooks peer-reviewed journal articles submissions from chiropractic colleges input from insurers B. to serve as voluntary guidelines for chiropractors to use when developing documentation systems for their offices. C. to encourage more uniform and more understandable clinical documentation, which should serve as a benefit to patients, providers, and insurers. The Wisconsin Chiropractic Association recognizes that the management of every individual patient is unique. Different styles of practice, or areas of clinical specialization, may prompt the doctor to vary the clinical information to be gathered and recorded. Documentation performed within the intent of these recommendations need not be rigid and inflexible, but should be adapted to the needs of a particular case. These guidelines are intended to provide a common framework for patient records which allows for more consistent reporting and improved communication. 2. Format: A SOAP format is regarded across the country as the most widely accepted method for keeping clinical records. This format records information about subjective complaints, objective findings, the doctor’s assessment and treatment plan in an organized manner. Used less frequently are recognized derivatives of the basic SOAP schema, such as POMR, SORE or SNOCAMP.1 2 3 1 Journal of Family Practice, Oct. 1995 41:4 Jordan E. St. Anthony’s guide to E/M coding and documentation. St. Anthony’s Publishing, Reston, VA 1995 2 9 An organized format [whether it is classic SOAP or a modification of the SOAP format] allows information to be recorded in a predictable, repetitive manner. Proprietary or “inoffice” systems of documentation are, by definition, difficult or impossible for a reviewer to understand. Abbreviations: The proper use of accepted abbreviations [such as those listed in these recommendations] can facilitate the documentation process by saving both record space and time. However, the use of non-standard abbreviations can lead to confusion in the interpretation of clinical records. Doctors who choose to utilize non-standard abbreviations should “translate” those abbreviations prior to the records being submitted to a third party. Methods: The methods used to complete clinical record keeping is a matter of preference for each practitioner. The doctor may prepare documentation by using dictation and transcription, narrative-style writing, pre-prepared forms or other methods preferred by the doctor. Documentation of evaluation/management services: During the course of a complicated case, the chiropractor may be presented with clinical situations which require varying complexities of decision making and/or the services required. The level of detail contained in the documentation will often increase as the complexity of the decision making or the complexity of the provided services increases. For example: at the onset of the complicated case, or at other critical time periods during the patient’s treatment, the chiropractor often functions at a specialist level. When functioning at that level, a corresponding increase in the detail of documentation is typically expected to fully detail the patient’s symptoms, findings, diagnosis and treatment plan. The chiropractor will usually choose to utilize a higher level [99204, 99205, 99214, 99215] evaluation/management code when performing these specialist-level services. at other times during the same case, the chiropractor may serve on a level very similar to a general practitioner. The level of documentation typically expected at this level is sufficient to tell the story of the patient, but may not include the full level of detail expected of the specialist-level documentation. The chiropractor will often use a mid-level [99202, 99203, 99212, 99213] evaluation/management code when performing these general practitionerlevel services. 3 Vernon H. Clinical note: S-O-R-E, a record keeping system for chiropractic treatment visits. Can Chir Assoc J. 1990;34:93. 10 on a daily treatment basis, the doctor is applying the treatment which has been fully described in the most recent treatment plan. Therefore, the documentation for daily visits will be much more concise. Chart organization: Clinical notes consist of three distinct elements: 1. Initial entry. The initial entry generally includes: pertinent baseline information about the patient the patient’s chief complaint[s] the results of initial physical examination the chiropractor’s assessment the recommended treatment plan 2. Daily note. The daily note represents a concise record of pertinent changes in the patient’s condition and treatment on that day. A series of daily notes will show changes on a visit-to-visit basis. The daily note is used most often to document: adjustment or manipulation physical modalities 3. Progress note. At different points in a case, a progress note is used to document additional patient services. These services may include: reevaluations reexaminations counseling coordination of care One respected author in the field of chiropractic documentation4 has described the initial entry as “SOAP-ing” the patient. He then explains that the progress note can be thought of as a kind of “midi-SOAP”, or a somewhat abbreviated version of the original SOAP work-up. This so-called “midi-SOAP” retains the same database format, yet is not necessarily as detailed as the original evaluation. The notation for a daily or routine visit is described as a “mini-SOAP”, displaying the same general organizational scheme of the of the initial evaluation, but on a significantly smaller scale. 3. Legibility: Clinical documentation should always be legible. If patient records are hand written, it is especially important that the handwriting is legible to the reviewer. If the handwriting is not legible to the reviewer, the provider should be informed and given the opportunity to transcribe the information. 4. Documentation of patient consent: Doctors should review with their legal counsel their responsibilities5 to obtain written proof of the patient’s consent in the following critical areas: 4 Mootz RD. Maximizing the effectiveness of clinical documentation. In: Top Clin Chiropractic 1994 1[1] p. 60-65. Aspen Publishers, Gaithersburg, MD. 5 Campbell L, Ladenheim CJ, Sherman R, Sportelli L. Informed consent: a search for protection. Top Clin Chiropractic 1994; 1 (30): 55-63. 11 general consent to examine and treat: Many doctors will have the patient complete this written consent as part of their initial patient questionnaire. informed consent: if any proposed treatment procedure poses a meaningful risk to the patient, the doctor is expected to disclose that risk to the patient and to document that the patient has consented to proceed with the proposed treatment. [In some cases in which the patient has significant difficulties communicating, such as Alzheimer’s disease, stroke victims or the mentally impaired, the informed consent should be obtained from a family member.] parent’s consent to examine and treat minor children: generally recommended before evaluating or treating any child under the age of 18. 5. The initial patient entry The initial entry generally includes pertinent baseline information about the patient, the patient’s chief complaint[s], the results of physical examination, the chiropractor’s assessment, the recommended treatment plan. An initial patient entry may be made anytime a patient presents with a new chief complaint. 5a. Subjective: Initial New Patient History This section forms the subjective area of the documentation. HCFA has recently defined elements which may be included in the subjective portion of the patient records6. The complexity of the patient’s health problems will determine which of these elements a chiropractor will choose to use in the patient’s record. A chiropractor’s records detailing problems of greater severity will generally include more of the these elements. It may not be necessary to include many of these elements in the records of patients with less severe problems. These elements of the subjective portion of clinical record keeping include the following: History of the present illness: [HPI] HCFA has defined the following factors to constitute a complete history of the present illness: history of trauma description of the chief complaint[s] onset of symptomatology palliative factors provocative factors quality of pain (burning, numbness, tingling) radiation of pain severity of pain (scale of 1-10) frequency or timing of complaint previous episodes of chief complaint. Reported in: St. Anthony’s Physician’s Claims and Billing Manager. St. Anthony’s Publishing, Reston, VA Vol. 3, No. 6, March 1995 6 12 As an alternative, the elements of the history of the present illness can be represented by the use of the mnemonic “O, P, Q, R, S, T”7. O = onset of symptoms P = provocative or palliative factors Q = quality of pain R = radiation S = severity of pain T = timing of pain When using this mnemonic, many doctors add an additional element to indicate whether the patient has experienced prior episodes of the chief complaint: U = previous episodes [have you ever had this problem before?] Past history: prior major illnesses and injuries prior operations prior hospitalizations current medications allergies (food or drug) age appropriate immunization status age appropriate feeding/dietary status. Social history: current employment occupational history (discretionary) use of drugs, alcohol, and/or tobacco other relevant social factors. Family history: Significant health factors which may be congenital or familial in nature should be noted. Review of systems: [ROS] HCFA has defined the following fourteen areas for review of systems: constitutional symptoms [fever, weight gain or loss, fatigue, etc.] eyes ears, nose and throat cardiovascular respiratory gastrointestinal genitourinary 7 Foreman S, Croft A. Whiplash injuries; the cervical acceleration/deceleration syndrome. 2 nd ed. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1995. 13 musculoskeletal integumentary [skin/breast] neurologic psychiatric endocrine hematologic/lymphatic allergic/immunologic Appendix A includes the requirements from HCFA for the proper coding of evaluation and management codes by the number of included elements from the elements of the history above. 5b. Objective: Initial New Patient Physical Examination This section forms the objective area of clinical documentation. The complexity of the patient’s health problems will determine which of these elements a chiropractor will choose to use in the patient’s record. A chiropractor’s records detailing problems of greater severity will generally include more of these elements. It may not be necessary to include many of these elements in the records of patients with less severe problems. The elements of the objective portion of the patient records may include the following: Vital signs height weight blood pressure [age dependent; recommended at initial exam, followup depending on condition] pulse [recommended at initial exam, then prn] respiration [if indicated by symptoms] temperature [if indicated by febrile symptoms] observation auscultation [if indicated by symptoms] percussion [if indicated by symptoms] palpation range of motion [Note that range of motion can be measured using many different methods, such as actively (AROM), passively (PROM) or active assisted (AAROM). In addition, range of motion can be measured visually, with a goniometer or a manual or electronic inclinometer. The doctor may wish to note the methods used to measure range of motion.] reflexes deep tendon: use of Wexler [0-5] scale superficial [if indicated by symptoms] pathologic [if indicated by symptoms] vascular examination [if indicated by symptoms] provocative orthopedic tests neurologic testing [if indicated by symptoms] 14 cranial nerves station, gait and balance sensory testing muscle strength testing: may be tested manually or with the use of various machines. When tested manually, most doctors use a modified Lovett scale, which assigns a number grade to the muscle strength8. The most common usage of this system uses 5 to indicate “normal”. Grades 4+, 4, and 4- are used to indicate decreasing muscle function within the “good” category, which is defined as the ability to raise the part against gravity and some resistance. Grades 3+, 3, and 3- are used to indicate decreasing muscle function within the “fair” category, which is defined as the ability to raise the part against gravity only. Grades 2+, 2, and 2- are used to indicate decreasing muscle function within the “poor” category, which is defined as the ability to raise the part only with gravity eliminated. Grade 1 means that the muscle contraction can be felt, but there is no joint movement. Grade 0 means no contraction is felt. the use of various types of instrumentation, leg length tests or other objective measurements which the chiropractor judges to be relevant to the case. 5c. Assessment: Initial New Patient Assessment Diagnostic impression in a narrative or descriptive format. Assessment of risk factors, if applicable. 5d. Plan: Initial New Patient Treatment Plan The complexity of the patient’s health problem will determine which of the following elements a chiropractor will choose to include in the patient’s record. It is not necessary to include all of these elements in the records of patients with less severe health problems. The elements of the treatment plan may include the following: Diagnostic treatment plan: describes the need for further tests, including reexamination, etc. Therapeutic treatment plan: describes the frequency and duration of adjustments and in-office therapies and modalities. Educational treatment plan: home exercises, modification of daily or work activities Short and long term goals Referral for other necessary services Coordination of care with other health professionals, if applicable 8 Legg AT, Physical therapy in infantile paralysis. In Mock. Principles and practice of physical therapy. Vol. II. Hagerstown, MD: WF Prior, 1932:45 15 6. Daily notes: The daily note represents a concise record of pertinent changes in the patient’s condition and treatment on that day. A series of daily notes will show the significant changes in the patient’s condition and treatment which occur over a period of time. The daily note is used most often to document ongoing treatment, such as adjustments/manipulation or physical modalities. After the initial entry, each subsequent office visit will usually be documented by a daily note, until the next specified reevaluation. If the initial entry clearly states the assessment and plan, it is not usually necessary to reevaluate the patient on a daily basis or to reiterate the assessment or the treatment plan. Any significant modification of the treatment plan should be recorded in the daily note.9 Because of its brevity, the daily note will list only the most important changes in the daily presentation of the patient, and the management of the case. Therefore, the treating chiropractor is best qualified to decide which objective and subjective elements of the case should be recorded via the daily note. 7. Progress notes At many different points in a case, a progress note is often used to document additional patient services. These services may include: reevaluations reexaminations counseling coordination of care 7a. Re-examination frequency: Periodic reexaminations of the patient are an important element of case management, and are used to assess the effectiveness of treatment. It may be appropriate to reexamine a patient or reevaluate a patient’s condition anytime there is a significant change in the patient’s symptoms or response to treatment. Reexaminations are especially important when a patient exacerbates their injury or if the clinical condition of the patient changes, which may indicate the need for the doctor to reassess the treatment plan. The following chart which describes typical frequency of reexaminations for established patients: 9 Bronston LJ. Record Maintenance and Narrative Writing. In: Ferezy JS. The Chiropractic Neurological Examination. Aspen, Gaithersburg MD, 1992, p. 153. 16 Patient type Definition Acute Chronic Supportive Maintenance or preventative Symptomatology is present less than six weeks Acute exacerbation of a chronic or recurring condition. Symptomatology present more than 18 weeks Symptomatology is present due to a known, permanent deficit; a full recovery is not expected. No active symptomatology. Typically, a reexamination is performed within: 30 days or 12 visits or as clinically indicated 3 months or 18 visits or as clinically indicated Six months to one year or as clinically indicated As clinically indicated A re-examination for an established patient is particularly appropriate in the following circumstances: a patient who presents with a new chief compliant a patient who presents with a new, distinct episode of a recurring condition. a patient who presents with symptoms, and has not received treatment for 90 days or more 8. Documentation of x-ray findings: X-ray documentation is usually produced on the day the film was read and/or billed. These x-ray findings may be in the form of a separate report, or may condensed to the major findings, and included with the objective portion of the patient’s documentation. Just as the “SOAP” format is used to methodically prepare patient records, formal x-ray reports often follow a repeatable format. When preparing formal x-ray reports, the following format has been advocated by Yochum and Rowe10: Introductory Information Letterhead Information Name of physician Clinic name and address Patient information Full name and address Date of birth File identification Radiographic information Views submitted Dates and location of films taken 10 Yochum TR, Rowe, LJ. Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, 2nd Ed. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1996, p.1371-1396. 17 Technique factors [optional] Report Clinical information Chief complaint Key clinical findings Reason for study Numbered summary of pertinent findings Radiologic findings Descriptive narrative of findings Findings are usually listed in the order of alignment, bone, cartilage, soft tissue, which can be easily remembered by the mnemonic “ABCs”. Conclusions Recommendations Indications or contraindications to treatment Follow-up procedures indicated Signature and qualifications 18 Chapter 2: Mechanisms of documentation There are many different mechanisms that a chiropractor may successfully use to keep excellent clinical documentation. Some of the most commonly used methods are discussed below: Dictation and transcription: Dictation of clinical records remains the benchmark against which all other forms of record keeping are measured. Dictation has many obvious advantages: impeccable legibility the ability to use as much detail as may be needed there are no restrictions imposed by the format itself transcriptionist does not need special computer training There are also minor disadvantages of the dictation/transcription method: labor intensive, therefore tends to be relatively costly dictation tapes can break or be lost digital dictation systems can lose data Computer-assisted record keeping [commercial programs]: These systems are available in many different formats. Various methods of inputting information to the computer have been devised, each claiming to be the most efficient. Information may be input into the computer via voice or through the use of keyboard, light pens, scanning sheets, touch screens, bar code readers or other devices. These systems have the advantages of: automating some of the repetitive aspects of patient records a comprehensive approach to inputting clinical data. Disadvantages may include: relatively high purchase cost relative difficulty of editing your copy from the pre-defined format in some of the products lost data if the system is not “backed up” frequently. With new technology comes intriguing new ethical questions. For example, some of the programs will automatically vary the verbiage to avoid the appearance of repetitive notes. There are computer programs which will “write” a narrative report or “calculate” a disability rating. Only the individual practitioner can decide if a particular product truly represents a time-saving tool in completing the patient’s documentation, or a clinically unacceptable “short cut”. 19 Word processing programs: All of today’s computer word processing programs have the ability to be easily programmed by the user to perform repetitive functions. These special, user-defined commands are usually called a macro. With the use of a macro, it is possible to automate many of the repetitive tasks required in patient record keeping, such as typing the clinic name, patient name, date and other commonly required data. In addition, a macro can generate frequently used text, often called boilerplate text. This can enable the doctor to add significant depth to records without expending much time. For example, complete instructions can be prepared for a routine of lumbar extension exercises. When a patient’s clinical condition indicates that these particular exercises are appropriate, the entire exercise routine can be added to the patient’s records with the touch of the macro button. The advantages of this type of system are: low cost system may be adapted completely to your needs and changed at any time The disadvantages of this type of system are: set-up is labor intensive professional assistance is seldom available doctors and staff must thoroughly understand the system they have devised data may be lost if not “backed up” frequently Hand written records: It is possible to keep excellent quality patient records by hand writing each record. However, many doctors will simply not be able to utilize hand written records because they possess illegible or poor quality handwriting. In addition, the sheer volume of information required in a quality patient record often lends itself to some sort of mechanization, especially in a busy practice. If hand written entries are to be part of clinical records: make sure that the handwriting is clearly legible be sure that the areas of the record reserved for handwriting are not cluttered with other information use only common, standardized abbreviations, such as those listed in these Wisconsin Chiropractic Association documentation recommendations. Proprietary or “in-office” chiropractic record keeping systems: Over the years, many chiropractors have developed proprietary [non-SOAP] formats or shorthand systems for various aspects of their patient records. These may include the use of abbreviations or symbols which are not well recognized within the chiropractic profession. The use of these types of devices within records can often be confusing to other parties who wish to review the patient’s records. This potential problem can often be avoided 20 by the use of standardized abbreviations and conventions, such as those described in these recommendations. Chapter 3: Outcome Assessment Measurement Devices Pain is the primary complaint for 80% of all office visits to physicians each year in the U.S. [National Center for Health Statistics, 1986]. It is important to use the proper measurement device in order to get meaningful data of a patient’s baseline status. The measurement must then be reapplied to get meaningful data of a patient’s improvement. The testing device must be comprehensive enough to give a reliable clinical picture, simple to understand, easy to score, and able to be administered at a low cost. The devices listed in bold are used very commonly within the chiropractic profession, and it is recommended that you become familiar with these outcome assessment devices. Unfortunately, copyright restrictions do not allow for the reproduction of these materials within these Wisconsin Chiropractic Association recommendations. Generally, you may access the original articles and use any of these devices in your office for the treatment of your individual patients. A. General health questionnaire 1. Health Status Questionnaire v.2.0 [Health Outcomes Institute, 1993]11 2. SF-36 [Stewart, 1988; Interstudy, 1990]12 3. RAND 36 [RAND Corporation, 1986]13 4. Dartmouth COOP charts [Nelson, 1987]14 15 16 5. Sickness Impact Profile [Bergner, 1981]17 6. Nottingham Health Profile18 B. Pain 1. Visual analog scale [VAS] [Huskisson, 1982]19 20 21 22 11 Health Outcomes Institute. Health Status Questionnaire 2.0. Health Outcomes Institute, Bloomington, MN 12 Interstudy: An introduction to Interstudy’s outcomes management system development plans. October, 1990. Interstudy, Excelsior, MN. 13 Rand 36-item health survey 1.0. Rand Health Sciences Program, Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1986, 1992. 14 Johnson D. Dartmouth COOP Project. Hanover, NY: Dartmouth Medical School, 1989. 15 Nelson E, Berwick D. The measurement of heath status in clinical practice. Medical Care 1989 27 [3]:S77 16 Kraus N. The Dartmouth primary care cooperative [“COOP] information project. Interstudy Qual Edge, 1991; 1:33-39. 17 Bergner M, Bobbitt R, Carter R, Carter W, Gilson B: The sickness impact profile: Development and final revision of a health status measure. Medical Care 1981, 19 [8]:787. 18 Reviewed in: Deyo RA. Measuring the functional status of patients with lower back pain. Chiropractic Technique. 1990;2[3]:127-137. 19 Huskisson S. Measurement of pain. J Rheumatol 1982, 9:768 20 Merskey H. The perception and measurement of pain, J Psychosom Res. 17:251-155, 1973. 21 Ventafridda V, DeConno F, DiTrapani P, Gallico S, Guarise G, Rigamonti G, and Tamurini M. A new method of pain quantification based on a weekly self-descriptive record of the intensity and duration of 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Numerical pain scale [NPS] [Jenson, 1986]23 McGill/Melzak pain questionnaire [Melzack, 1975]24 Pain drawing [Mooney and Robertson, 1976] 25 26 Pain Disability Index [Tait, 1987]27 Dallas Pain Questionnaire [Lawlis, 1989]28 29 C. Disability: lower back pain 1. Modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Questionnaire [Fairbank, 1980]30 31 2. Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire ROL-SIP [Roland, 1983]32 3. Low Back Pain TyPE Specifications [Health Outcomes Institute, 1992]33 4. Million Disability Questionnaire [Million, 1982]34 5. Waddell Disability Index [Waddell and Main, 1984]35 D. Disability: cervical or headache 1. Neck Disability Index [Vernon-Mior, 1991]36 2. Headache Disability Index: HDI [Jacobson, 1994]37 E. Pychometrics pain. In Bonica JJ, Lindblom U Iggo A eds: Advanceds in pain research and therapy, Vol 5: Proceedings of the Third World Congress on Pain. 22 Jensen MP, Koroly P, O’Riordan EF, et al: The subjective experience of actual pain: an assessment of the utility of 10 indices. Clin J. Pain 5:153, 1989. 23 Jensen M, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: A comparison of six methods. Pain 1986, 27: 117. 24 Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975, 1:277. 25 Mooney V. Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop 115:149, 1976. 26 Rainsford AO, Cairns D, Mooney V. The pain drawing as an aid to the psychologic evaluation of patients with lower back pain. Spine 1:127-134. 1974. 27 Tait R, Pollard C Margolis R, Duckro P, Krause S. Pain disability index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987, 68:438. 28 Review in: White A, Schofferman J. ed. Spine Care. Mosby, St. Louis, 1995. P. 919-922. 29 Lawlis GF, Cuencas R, Selby D, et al. The development of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire for illness behaviour. Spine 14:511, 1989. 30 Fairbanks J, Davies J, Couper J, O’Brien J. The Oswestry low-back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980, 66:271. 31 Hudson-Cook N, Tomes-Nicholson K, Breen A. The revised Oswestry low back pain questionnaire. Thesis, Anglo-European College of Chiropractic, 1988. 32 Roland M, Morris R. Study of natural history of back pain, part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low back pain. Spine 8:141; 1983. 33 Health Outcomes Institute. Low Back Pain TyPE Specifications. Health Outcomes Institute, Bloomington, MN 34 Million R, Nilsen K, Jayson MIV, et al. Evaluation of lower back pain and assessment of lumber corsets with and without back supports. Ann Rheum Dis 40:449, 1981. 35 Waddell G, Main C: Assessment of severity in low-back disorders. Spine, 1984, 9:204. 36 Vernon H, Mior S. The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manip Physio Ther 1991, 14 [7]:409. 37 Jacobson GP, Ramadan NM et al. The Henry Ford Hospital Headache Disability Inventory [HDI]. Neurology 1994;44:837-842. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Psychosocial Pain Inventory [Heaton, 1980]38 Illness Behaviour Questionnaire [Pilowsky, 1976]39 Health Status Questionnaire 2.0 40 [Questions 37-39: depression screens] Waddell Non-Organic LBP signs [Waddell, 1980] 41 Somatic Amplification Rating Scale [Korbon, 1987]42 Modified Zung Depression Index 43 44 Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire MSPQ [Main, 1983]45 Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory [MMPI]46 47 Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire FABQ [Waddell, 1993]48 F. Patient satisfaction: 1. Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire [Ware, 1983]49 2. GHAA Consumer Satisfaction Survey [Ware, 1991]50 3. Low Back Pain Patient Satisfaction [Deyo, 1986]51 4. Chiropractic Satisfaction Questionnaire [Coulter, 1994]52 38 Heaton RK, Lehman RAW, Getto CJ. Psychosocial Pain Inventory, Odessa, FL, 1980, Psychological Assessment Resources. 39 Pilowsky, I, Spence ND. Illness behaviour syndromes associated with intractable pain. Pain 2:61-71, 1976. 40 Health Outcomes Institute. Health Status Questionnaire 2.0. Health Outcomes Institute, Bloomington, MN 41 Waddell G, McCulloch J, Kummel E, Venner R. Non-organic signs in low back pain. Spine 5:117, 1980. 42 Korbon GA, DeGood E, Schroeder ME, et al. The development of a somatic amplification scale for lower back pain. Spine. 1987;12[8]: 787-791. 43 Zung W. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;32:63-70/ 44 Review in: Ahles TA, Yunus MB, Mari AT. Is chronic pain a variant of depressive disease? The case of primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain, 1987; 29: 105-111. 45 Main C. 1983 Modified somatic perception questionnaire. J. Psychosom Res. 1983;27:503-514. 46 Hanvik LJ. MMPI Profiles in patients with lower back pain. J. Consul Psychol. 15:350-353, 1951. 47 Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: manual for administation and scoring. Psychological Corporation, New York, 1967. 48 Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, et al. A fear-avoidance beliefs [FABQ] questionnaireand the role of fear avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993:52:157-168. 49 Ware J, Davies AR. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Eval and Program Plan. 1983;6:247-263. 50 Davies AR, Ware JE. GHAA’s consumer satisfaction survey and user’s manual. 2 nd ed. Washington, DC: GHAA: 1991. 51 Deyo R, Diehl A. Patient satisfaction with medical care for low back pain. Spine 1986, 11:28. 52 Coulter I, Hays R, Danielson C. The chiropractic satisfaction questionnaire. Topic in Clin Chiropractic. 1994; 1[4]: 40-43. Chapter 4: A Primer on Chiropractic Listings Chiropractors use a variety of different systems to indicate the deviation of a motor unit from its normal position. While a comprehensive survey is far beyond the scope of this document, the following information should prove helpful to anyone attempting to understand a chiropractic listing. Spinal segments: The following abbreviations are commonly used to refer to segments of the spinal column and pelvis: C0, O: Occiput OC: Occipital condyle C1, A: Atlas C2, AX: Axis C3: Third cervical C4: Fourth cervical C5: Fifth cervical C6: Sixth cervical C7: Seventh lumbar T1: First thoracic [or dorsal] T2: Second thoracic T3: Third thoracic T4: Fourth thoracic T5: Fifth thoracic T6: Sixth thoracic T7: Seventh thoracic T8: Eighth thoracic T9: Ninth thoracic T10: Tenth thoracic T11: Eleventh thoracic T12: Twelfth thoracic L1: First lumbar L2: Second lumbar L3: Third lumbar L4: Fourth lumbar L5: Fifth lumbar S: Sacrum S1: First sacral segment S2: Second sacral segment S3: Third sacral segment S4: Fourth sacral segment S5: Fifth sacral segment CO: Coccyx IL: Ilium Additionally, some of the prominent landmarks of spinal segments are abbreviated below. These landmarks are often used as points of reference to define the orientation of the vertebra within a three-dimensional space: SP: spinous process TP: transverse process M: mamillary process L: lamina P: pedicle B: body Direction of Vertebral Misalignment: A bone or spinal segment is usually “listed” in the direction it deviates from normal. The following abbreviations are commonly used. The international coordinate system53, which is often used in biomechanical research, is described in parenthesis: Two-Dimensional Translational Motion: A: Anterior (+Z) P: Posterior (-Z) R: Right (-X) L: Left (+X) S: Superior or cephalad (+Y) I: Inferior or caudal (-Y) EX: External IN: Internal Three-Dimensional Motion: Clockwise rotation: (+) Counterclockwise rotation: (-) F: Flexion (+X) E: Extension (-X) LLF: Left lateral flexion (-Z) RLF: Right lateral flexion (+Z) RR: Right spinous rotation (+Y) LF: Left spinous rotation (-Y) Examples of Combination Listings: These two components of location and direction are often combined to describe a bone or motor segment which has deviated from its normal position. For example, L5 PL: C6 PLI-BR: T6 RP: 53 5th lumbar vertebra has deviated with spinous moved to the left. 6th cervical vertebra has deviated with its body moved to the right. 6th thoracic vertebra has deviated with the body posterior on the right. White A, Panjabi M. Clinical biomechanics of the spine. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1978 106752870 Chapter 5: Glossary The following glossary is essentially limited to terms which involve the process of documentation. In addition, definitions are suggested for some terms which are used in so many different contexts, [such as acute and chronic] that they have become difficult to define accurately. AAROM: Active assisted range of motion. The patient is asked to perform voluntary movement of the joint throughout its arc of movement, and the examiner applies a mild force in the same direction as the patient’s movement. The purpose is to ensure that full range of motion has been measured, and to assess the quality of the joint movement upon reaching the endpoint of movement. Acute: having symptomatology for a relatively short length of time. A common definition is symptoms which are noticed for less than 6 weeks upon presentation.54 AROM: Active range of motion, performed with the patient voluntarily moving the joint. The examiner is looking for differences in range of motion and the patient’s willingness to perform the movement.55 Assessment: The portion of the patient clinical record which details the doctor’s impression, diagnosis or opinions of the case. Chief complaint: The patient’s primary health concern which results in seeking treatment from the doctor. Chronic: having symptomatology for an extended length of time. A commonly accepted criteria for a chronic complaint is symptomatology which are apparent for more than 16 weeks upon initial presentation.56 Disability: The alteration of an individual’s capacity to meet personal, social or occupational demands, or statutory or regulatory requirements because of an impairment. Disability refers to an activity or task the individual cannot accomplish.57 Disability is the inability to perform specific work-related activities. Disability is a functional deficit. Impairment: The loss, loss of use or derangement of any body part, system, or function. Impairments are defined as conditions that interfere with an individual’s “activities of daily living”, or the inability to perform certain physical tasks, which may or may not be associated with work activities58. An impairment is an anatomic deficit. Maintenance care: 1. Treatment given in the absence of significant symptomatology; 2. well-person care; 3. preventative or prophylactic care 54 Fromeyer J. Back Pain and Sciatica. N Engl J Med., 318:291-300, 1988 Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1992. 56 Mayer T, Gatchel R. Functional restoration for spinal disorders: a sports medicine approach. Leee & Febiger, Philadelphia, 1988. 57 American Medical Association. Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, 4 th ed. AMA, Chicago, 1993. 58 American Medical Association. Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, 4 th ed. AMA, Chicago, 1993. 55 27 Objective: Items in the patient record which can be accurately and repeatedly measured. OPQRST: A mnemonic device for the essential elements of the history of the present illness. The initials represent: onset, palliative and provocative factors, quality of pain, radiation, severity, and timing (frequency). Plan: Treatment plan; a written outline of the proposed care for the patient PROM: Passive range of motion. The patient is asked to relax as much as possible, and the examiner supplies all the force necessary to move the joint throughout its arc of movement. Passive testing is usually performed if deficits in active range of motion are noted. SOAP: A mnemonic for subjective, objective, assessment, plan. Sub-acute: symptoms which are present for a period greater than an acute presentation, and less than a chronic presentation. A commonly accepted definition of sub acute would be the presence of symptomatology for 6-16 weeks upon initial presentation. Subjective: Items in the patient record which are derived from the patient’s verbal or written communications with the doctor. Supportive care: 1. Treatment provided after the patient has reached maximum medical/chiropractic improvement and has not reached a full recovery; 2. treatment given to diminish permanent or chronic symptomatology when a full recovery is not possible; 3. treatment provided to alleviate the symptomatology of a known anatomic deficit. 28 Chapter 6: Commonly used abbreviations The abbreviations listed below do not represent a comprehensive listing, or an attempt to replace a medical dictionary. These abbreviations are often used by chiropractors , and originate in the following areas: 1. Commonly encountered diagnoses 2. Commonly used abbreviations describing patient symptomatology in daily or progress notes. 3. Commonly used anatomic abbreviations. Note that some of the abbreviations can take on different meanings, depending upon the context. For example, the abbreviation “P” can mean either “pulse” or “treatment plan”, depending upon its usage. >: greater than <: less than : arc : frequency : change : decreased : increased : none, no : right L : left B : bilateral ~: approximately 1: primary 2: secondary 3: tertiary a.: before A: assessment a.c.: before meals AAROM: active assisted range of motion ab: abdominal AC: acromioclavicular ad feb.: fever present ad int.: in the interim ad lib.: as wanted adj.: adjustment adl: activities of daily living agg: aggravate ant.: anterior AP: anteroposterior AROM: active range of motion AS: ankylosing spondylitis b.i.d.: twice per day B: bilateral B/B: Bowel/bladder BCP: birth control pills BM: bowel movement BP: blood pressure BX: biopsy c: with c/o: complains of C: cervical CA: carcinoma CB: contrast bath CBC: complete blood count CBR: complete bed rest cerv: cervical cmt: chiropractic manipulative therapy 29 COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease CP: cold packs CP: cerebral palsy cp: cervical pain c-s: cervical spine c-t: cervicothroacic csa: chiropractic spinal adjustment CT: computed tomography ctd: cumulative trauma disorder cts: carpal tunnel syndrome CVA: cerebrovascular accident CVP: central venous pressure D: dorsal [syn. thoracic] D/C: discontinue DD: differential diagnosis DDD: degenerative disc disease DIP: distal interphalangeal joint dimin: diminished DJD: degenerative joint disease DRG: dorsal root ganglion DSLR: double straight leg raise DTR: deep tendon reflex Dx: diagnosis ECG or EKG: electrocardiogram EEG: electroencephalogram EMG: electromyography ems: electrical muscle stimulation EPP: end point pain ES: erector spinae muscles ESI: epidural steroid injection ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate exacer: exacerbation ext: extension FBG/FBS: fasting blood glucose/sugar FH: family history fix: fixation flex: flexion FUO: fever of unknown origin Fx: fracture G-H: Gleno-humeral GI: gastrointestinal GU: genitourinary HA: headache Hb or Hgb: hemoglobin Hct: hematocrit HEENT or EENT: head/eyes,ears,nose,throat hmp: hot moist packs HNP: herniated nucleus pulposis hpi: history of present illness HR: heart rate HTN: hypertension hv: high volt HVG: high volt galvanism Hx: history ice mass: ice massage IF, IFC: interferential current im: intermittent imp: improved inf.: inferior iso: isometric IT, IST: intersegmental traction ITB: iliotibial band IUD: intrauterine device ivd: intervertebral disc ivf: intervertebral foramen JVP: jugular venous pressure KJ: knee jerk L or lum: lumbar L or Lt: left lat: lateral LATX: long axis traction LBP: lower back pain lbp: lower back pain LC: lower cervical LD: lower dorsal LE: lower extremity llf: left lateral flexion LLI: leg length inequality LLQ: left lower quadrant lm: lateral meniscus LMN: lower motor neuron lr: left rotation lum or L: lumbar L/S: lumbosacral 30 l-s: lumbar spine LT: light touch [sensation] LUQ: left upper quadrant lv: low volt m: muscle mass: massage mbp: midback pain MCP: metacarpophalangeal joint MCRC: maximum cervical rotatory compression MCV: mean cell volume med: medial MI: myocardial infarction MLR: maximum lifting restriction mm.: muscles mm: medial meniscus mp: motion palpation MTP: midthoracic pain or metatarsalphalangeal joint MVA: motor vehicle accident myo: muscle n: nerve nad: no abnormalities detected NBM or NPO: nothing by mouth NCV: nerve conduction velocity NKC: no know cause NKI: no known injury n/l: normal limits nn.: nerves nr: nerve root NSR: normal sinus rhythm O: objective OA: osteoarthritis OB/GYN: obstetrics and gynecology OC: oral contraceptive oc: office call occ.: occipital occ.: occasional OTC: over the counter p: after P: Plan P: pulse p.c.: after meals p.r.n.: as needed pap.: papanicolaou smear PE: physical examination PERRLA: pupils equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation PFA: patellofemoral arthralgia PH: past history phono: phonophoresis PIP: proximal interphalangeal joint PMI: point of maximum intensity pn, px.: pain PND: postnasal drainage PNF: proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation PPD: permanent partial disability prn: whenever necessary; as needed PROM: passive range of motion PT: physical therapy Pt. ed.: patient education Pt., pt.: patient PT: physical therapist PVC: premature ventricular contraction px, pn: pain q.a.m.: every morning q.d.: every day q.h.: every hour q.i.d.: four times per day q.o.d.: every other day q.p.m.: every afternoon/evening QL: quadratus lumborum R: respiration RA: rheumatoid arthritis rad: radiate, radiation rlf: right lateral flexion RLQ: right lower quadrant RTW: return to work RO, R/O: rule out ROM: range of motion rr: right rotation RUQ: right upper quadrant Rx: therapy or prescription Rx: medication s: without 31 S: subjective S: sacral SA: sacral apex sa: spinal adjustment SB: sacral base SC: sternoclavicular joint SCM: sternocleidomastoidious muscle sho: shoulder SI: sacroiliac joint SLR: straight leg raise test sm: spinal manipulation smt: spinal manipulative therapy SOB: shortness of breath SP: spinous process spondy: spondylolisthesis SSLR: sitting straight leg raise test ST: sharp touch [sensation] Stat.: immediately, at once STM: soft tissue massage sup.: superior SWD: short-wave diathermy Sx: symptoms T: temperature T: thoracic Telecon: telephone conversation t.i.d.: three times per day thor: thoracic TIA: transient ischemic attack T/L: thoracolumbar TMJ: temporomandibular joint tos: thoracic outlet syndrome TP: trigger point TPD: temporary partial disability TPR: temperature, pulse and respiration TPT: trigger point therapy trap: trapezius t-s: thoracic spine tt: taut and tender TTD: total temporary disability ttt: tender to touch tx, txrn: traction Tx: treatment Tx: telephone call UA, U/A: urine analysis UE: upper extremity UMN: upper motor neuron URI: upper respiratory infection US: ultrasound UTI: urinary tract infection UV: ultraviolet VSC: vertebral subluxation complex WLR: well leg raise test WNL: within normal limits w/o: without WP: whirlpool x: number of times performed [x2 = twice; x3 =three times, etc.] XR: x-ray yo: years old z-joint: zygapophyseal joint 32 Appendix A The Health Care Financing Administration has recently produced guidelines which address the level of history recommended for each particular evaluation/management code. The HCFA guidelines specify which factors must be included to qualify for a particular history, as well as the documenting factors which must be included. The history is one factor which determines proper evaluation/management code selection. The factors and their use are summarized in the chart below: Possible choices for E/M code Type of History [used to determine proper E/M code] History of Present Illness [HPI] the location of the problem the quality the severity of the problem the duration of the problem the timing of the problem the context modifying factors associated signs and symptoms 99201 99212 99202 99213 Problemfocused Expanded problemfocused Detailed Brief (1-3 of the above factors) Brief (1-3 of the above factors) Extended (4 or more of the above factors) Extended (4 or more of the above factors) 99203 99214 99204 99205 99215 Comprehensiv e Review of Systems [ROS] eyes ears, nose, throat and mouth cardiovascular respiratory gastrointestinal genitourinary musculoskeletal integumentary neurologic psychiatric endocrine hematologic or lymphatic allergic or immunologic N/A Past Family and/or Social History [PFSH] Past history Family history Social history Problem-pertinent (1 of the above systems reviewed ) Extended (2-9 of the above systems reviewed) Complete (10 or more of the above systems reviewed) N/A N/A Pertinent (1) Complete (2 or 3) 33 Appendix B: Selected bibliography and reading list 1. Arnoff GM, ed. Evaluation and treatment of chronic pain. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1992. 2. Baird, R. Health record documentation: charting guidelines. Digest Chiropractic Econ 1981; 52: 32-3. 3. Bates, B. A guide to physical examination and history taking, 5th ed. Lippincott, Philadelphia. 1991. 4. Boone W, et al. Practice Guidelines for Straight Chiropractic. World Chiropractic Alliance, Chandler, AZ. 1993. 5. Braddom RL, ed. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. WB Saunders, London, 1996. 6. Camins M, O’Leary P. Disorders of the cervical spine. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1992. 7. Curl, DD. Chiropractic approach to head pain. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994. 8. Croft AC. Chief complaints in narrative reports. In: Dynamic Chiropractic, May 6, 1994. Motion Palpation Institute, Huntington Beach, CA. 9. Evans RC. Illustrated essentials in orthopedic physical assessment. Mosby, St. Louis, 1994. 10. Ferezy, JS. The chiropractic neurological examination. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD 1992. 11. Foreman S, Stahl M. Medical-legal issues in chiropractic. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1990. 12. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research. Proceedings of the 1991 International Conference on Spinal Manipulation. FCER, 1701 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington, VA, 1991. 13. Gatterman, MI. Chiropractic management of spine related disorders. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1990. 14. Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Peterson, D. Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters: Proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference, Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD. 1993. 15. Haldeman S. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. Appleton and Lange, Norwalk, CT, 1992. 16. Hanson D. Determining how much care to give and reporting patient progress. In Topics of Clinical Chiropractic, 1[4]; 1-8. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD 1994. 17. Hislop HJ, Montgomery J. Daniels and Worthington’s Muscle Testing, 6th edition, Techniques of Manual Examination. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD 1995. 18. Hochschuler S, Cotler B, Guyer R. Rehabilitation of the spine: science and practice. Masby, St. Louis, 1993. 34 19. Hoppenfeld S. Physical examination of the spine and extremities. Appleton and Lange, Norwalk, CT, 1976 20. Jordan, E. St. Anthony’s guide to E/M coding and documentation. St. Anthony’s, Reston, VA, 1995. 21. Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG. Muscles: testing and funciton, 4th edition, with posture and pain. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD 1993. 22. Kettenbach G. Writing SOAP notes. FA Davis, Philadelphia, 1990. 23. Lawrence, KE, et al. Chiropractic patient resource manual. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD 1993. 24. Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the spine: a practitioner’s manual. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1996. 25. Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Saunders, Philadelpia, 1992. 26. Maigne R. Diagnosis and treatment of pain of vertebral origin: a manual medicine approach. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1996. 27. Mootz RD. Maximizing the effectiveness of clinical documentation. Topics Clin Chiropractic. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD 1994; 1[1] 60-65. 28. National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA Accreditation Manual. NCQA, 1350 New York Ave, NW., Suite 700, Washington, DC 20005, 1995. 29. Ombregt L, Bisschop P, ter Veer H, Van de Velde T. A system of orthopaedic medicine. WB Saunders, London, 1995. 30. Plaugher G, Lopes M. Textbook of clinical chiropractic: a specific biomechanical approach. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD 1993. 31. Sweere, J, ed. Chiropractic family practice. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD 1992. 32. Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, 1983. 33. Vear H. Chiropractic Standards of Practice and Quality of Care. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD, 1992. 34. Vear, HJ. Chiropractic standards of practice and quality of care. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD 1992. 35. White A, Anderson R. Conservative care of lower back pain. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1991. 36. White AH, Schofferman JA. Spine Care: Volume 1: Diagnosis and Conservative Management. Mosby, St. Louis, 1995. 37. Yochum TR, Rowe, LJ. Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, 2nd Edition, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1996. 35 CHART AUDIT CHECKLIST 1. Billed services are documented (X-ray, PT, rehab) 2. Special studies performed include explanation of why the test is necessary and a description of the impact the test(s) had on treatment &/or diagnostic decisions 3. Diagnosis made is supported by the findings of the case 4. Legibility 5. List risk factors of a prolonged recovery (See appendix A) Conditions – diabetes, cardiovascular disease, CNS disorders, medication interactions, etc. Yellow flags (depression, anxiety, poor coping strategies, fear avoidant behavior, job dissatisfaction, etc.) 6. Treatment Plan - included? Followed? 7. Periodic recheck and updated treatment plan. Followed? 8. Exacerbations affect recovery? Home vs. work? 9. Were work restrictions/modifications issued? Followed? 10. Outcomes oriented documentation 11. Goal oriented management 12. Use of the Appeal process 13. Reasons for care denial a. Insurance letter/opinion b. Based on consultant file review (MD vs. DC vs. "anonymous"; qualifications included?) c. Based on IME d. Guidelines cited e. Records reviewed listed? 14. MMI reached? If so, when? If not, any predictions or special tests needed before MMI is reached? 15. Treatment effectiveness 16. Pertinent past history findings (list & describe impact to the current case) 17. Rehabilitation (progression from passive to active care) a. Anything more than "exercises given" listed? How frequently? Any followup? Any objective physical testing pre-/post-rehab to document outcomes? b. If multiple units (each 15 minutes) - is this clearly documented (what was performed, SOAP approach for rehab service, "scorecard" of performance, etc.) 18. Was each page signed & dated? 36 APPENDIX A Risk factors of chronicity & Yellow Flags A. Risk factors (Documentation): 1. Abnormal illness behavior (Waddell's, SF-6) 2. Job dissatisfaction 3. Past Hx of >4 episodes 4. Symptoms > 1 wk w/o health provision 5. Severe pain intensity (Triple VAS) (>69%) 6. New condition / injury related to pre-existing structural pathology or skeletal anomaly 7. Weak back extensor musculature (Static back endurance test) 8. Smokes 1 pack or greater / day 9. Poor self-rated health (SF/HSQ-36 or -12) 10. Heavy Job Classification B. Yellow Flags Yellow Flags Symptoms Yellow Flag Reference Number of pain sites Duration of symptoms Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997 Cherkin, 1996; Von Korff, 1993; Linton 1998; Linton 1997 Duration of symptoms before the 1st visit Van den Hoogen, 1997 Past history of numerous episodes Frank, 1996; Cherkin, 1996; Hazard, 1996; Burton, 1995 Past hospitalization or surgery for similar Van den Hoogen, 1997; Hazard, 1996; Lancourt, complaint 1992 Severe pain intensity Frank, 1996; Cherkin, 1996; Von Korff, 1993; Linton, 1998; Hazard, 1996 Frequency of painful episodes over the last Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997 3 months Sciatica Frank, 1996; Cherkin, 1996; Burton, 1995; Salim, 1998; Lancourt, 1992 Psycho-social Anxiety Locus of control Depression Cherkin, 1996 Burton, 1995 Cherkin, 1996; Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997; Klennerman, 1995 37 Catastrophizing Self-rated health as poor Heavy smoker Belief that you shouldn’t work with your current pain Job dissatisfaction Anticipation of trouble sitting or standing at work 6 weeks into the future Anticipation of disability 6 months into the future Function Does physical activity make your pain worse? Tolerance for light work Is sleep affected by your pain? Disability Heavy job demand Past disability for the same/similar complaint in prior 12 months Disabled at present Burton, 1995 Cherkin, 1996; Waddell, 1996 Waddell, 1996; Cats-Baril, 1991; Hazard, 1996 Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997 Cherkin, 1996; Cats-Baril, 1991 Hazard, 1996 Hazard, 1996 Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997 Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997 Linton, 1998; Linton, 1997 Waddell, 1996 Hazard, 1996 Hazard, 1996 38 APPENDIX B: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Services Supervised Modalities Code 97010 97012 97014 97016 97018 97020 97022 97024 97026 97028 Description Hot or cold packs Traction, mechanical Electrical stimulation (unattended) Vasopneumatic devices Paraffin bath Microwave Whirlpool Diathermy Infrared Ultraviolet RVU* .29 .46 .40 .45 .33 .28 .38 .29 .27 .28 Constant Attendance Code Description RVU* 97032 Electrical stimulation (manual), each 15 minutes .40 97033 Iontophoresis, each 15 minutes .42 97034 Contrast baths, each 15 minutes .32 97035 Ultrasound, each 15 minutes .33 97036 Hubbard tank, each 15 minutes .51 97039 Unlisted attended modality (specify type and time) .47 Table 1. The use of modalities in a musculoskeletal practice is common. Various attended and non-attended or supervised modalities are described. The Relative Value Units are located in the right hand column. Table 2. Treatment Services 97110 Therapeutic procedure, one or more areas, each 15 minutes; OR, Therapeutic exercises to develop strength and endurance, range of motion and flexibility 97112 Neuromuscular reeducation of movement, balance, coordination, kinesthetic sense, posture, and proprioception, ea. 15 min. 97113 Aquatic therapy with therapeutic exercises, ea. 15 min. 97116 Gait Training (includes stair climbing), ea. 15 min. 97124 Massage, including effleurage, petrissage and/or tapotement (stroking, compression, percussion) 97139 Unlisted therapeutic procedure (specify) ea. 15 min. 97140 Mobilization, manipulation, manual traction, lymphatic drainage, ea. 15 minutes 97150 Therapeutic procedure(s), group (2 or more individuals) 97504 Orthotics fitting and training upper and/or lower extremities; each 15 minutes 97520 Prosthetic fitting and training upper and/or lower extremities; each 15 minutes .60 .59 .66 .52 .47 .49 .61 .62 39 97530 Therapeutic activities, direct (one on one) patient contact by the provider (use of dynamic activities to improve functional performance), each 15 minutes 97535 Self care/home management training (e.g., activities of daily living and compensatory training, meal preparation, safety procedures, and instructions in use of adaptive equipment) direct one on one contact by provider, each 15 minutes. 97537 Community /work reintegration training (e.g., shopping, transportation, money management, avocational activities and/or work environment/modification analysis), work task analysis, direct one on one contact by provider, each 15 minutes. [for wheelchair management/propulsion training, use 97542, each 15 minutes] 97542 Wheelchair management/propulsion training, each 15 minutes 97545 Work hardening/conditioning; initial 2 hours 97546 each additional hour Table 2. A listing of treatment services is found in this table with the associated CPT code number. NE stands for Not Established. .63 .64 .64 .44 NE NE Table 3 Tests and Measurements (For muscle testing, manual or electrical, joint range of motion, electromyography or nerve velocity determination, see 95831-95904) 97703 Checkout for orthotic/prosthetic use, established patient, each 15 .46 minutes 97750 Physical performance test or measurement (e.g., musculoskeletal, .72 functional; capacity), with written report, each 15 minutes Other Procedures 97770 Development of cognitive skills to improve attention, .75 memory, problem solving., includes compensatory training and/or sensory integrative activities, direct (one-on-one) patient contact by the provider, each 15 minutes 97780 Acupuncture, on or more needles; without electrical NE stimulation 97781 With electrical stimulation NE 97799 Unlisted physical medicine service or procedure NE th * Taken from: 6 Annual edition 1998 ChiroCode DeskBook, Leavitt Crandall Institute, Inc. Mesa, AR, 1997 Table 3. When tests or measures are performed, specific CPT codes can be assigned to the service. When other services such as acupuncture is performed, CPT codes specific to those services are also available. 40 Bibliography: Alaranta H, Rytokoski U, Rissanen A, et al. Intensive physical and psychosocial training program for patients with chronic low back pain. Spine 1994;19:1339-1349. Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al. Acute low back problems in adults. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1994. Bolton JE. Evaluation of treatment of back pain patients: clinical outcome measures. European J of Chiro 1994;42:29-40. Burke SA, Harms-Constas CK, Aden PS. Return to work/work retention outcomes of a functional restoration program. Spine 1994:17;1880-1886. Burton CV, Cassidy JD. Economics, epidemiology, and Risk Factors. In: Managing Low Back Pain, 3rd ed. Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Burton CV eds., Churchill-Livingstone, New York; p2. Burton AK, Tillotson K, Main C, Hollis M. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and sub-acute low back trouble. Spine 1995;20:722-8. Butler RJ, Johnson WG, Baldwin ML. Managing work disability: why first return to work is not a measure of success. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1995;48(3):452-469. Cats-Baril WL, Frymoyer JW. Demographic factors associated with the prevalence of disability in the general population: Analysis of the NHANES I database. Spine 1991;16:671-674. Cheadle A, Franklin G, Wolfhagen C, Savarino J, et al. Factors influencing the duration of work-related disability. Am J of Pub Health 1994;84 (2);190-196. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Street JH, Barlow W. Predicting poor outcomes for back pain seen in primary care using patients’ own criteria. Spine 1996;21:2900-2907. Cherkin DC, MacCornack. Patient evaluations of low back pain care from family physicians and chiropractors. West J Med 51:355, 1989. Croft PR, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Silman AJ. Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ 1998;316:1356-1359. Cutler RB, Fishbain DA, Rosomoff HL, Abdel-Moty E, et al. Does nonsurgical pain center treatment of chronic pain return patients to work? A review and meta-analysis of the literature. Spine 19 (1994) 643-652. Deyo RA. Low back pain - A primary care challenge. Spine 1996;21:2826-2832. 41 Flor H. Fydrick T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: A meta-analytic review. Pain 49 (1992) 221-230. Fordyce WE, Brockway JA, Bergman JA, Spengler D. Acute back pain: a control-group comparison of behvorial vs traditional management methods. J Behav Med 9 (1986) 127140. Frank JW, Kerr MS, Brooker AS, DeMaio SE, Maetzel A, et al. Disability resulting from occupational low back pain. Part 2: What do we know about secondary prevention? Spine 1996;21:2918-2929. Frost H, Lamb SE, Klaber Moffett JA, Fairbank JCT, Moser JS. A fitnes programme for patients with chronic low back pain: 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pain 75 (1998) 273-279. Goosens MEJB, Evers SMAA. Economic evaluation of back pain interventions. J Occup Rehab 7 (1997)15-32. Hazard RG, Haugh LD, Reid S, Preble JB, MacDonald L. Early prediction of chronic disability after occupational low back injury. Spine 1996;21: 945-951. Hazard RG, Fenwick JW, Kalisch SM, et al. Functional restoration with behavioral support. Spine 1989; 14:157-161. Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O. Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered: A randomized clinical trial. Spine 1995;20:473-7. Kendall NAS, Linton SJ, Main CJ. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: Risk factors for long-term disabilty and work loss. Accident Rehabilitation & Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee 1997. Wellington, NZ. Klenerman L, Slade P, Stanley I, et al. The prediction of chronicity in patients with an acute attack of low back pain in a general practice setting. Spine 1995;20:478-84. Lancourt J, Ketteljut M. Predicting return to work for lower back pain patients receiving worker's compensation. Spine 1992;17:629-640. Lindstrom A, Ohlund C, Eek C, et al. Activation of subacute low back patients. Physical Therapy 1992;4:279--293. Linton SJ, Hellsing AL, Hallden K. A population based study of spinal pain among 35-45 year olds: prevalance, sick leave, and health care utilization. Spine 1998 in press. Linton SJ, Hallden BH. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain 1998:14;1-7. 42 Linton SJ, Hallden K. Risk factors and the natural course of acute and recurrent musculoskeletal pain: Developing a screening instrument. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Pain, Progress in Pain Research and Management, Vol 8, ed. Jensen TS, Turner JA, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, IASP Press, Seattle, 1997. Linton SL, Hellsing AL, Andersson D. A controlled study of the effects of an early active intervention on acute musculoskeletal pain problems. Pain 1993;54:353-359. Malmivaara A, Hakkinen U, Aro T, et al. The treatment of acute low back pain - bed rest, exercises, or ordinary activity? N Engl J Med 1995;332:351-5. Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, Mayer H, Kishino ND, Keeley J, Mooney V. A prospective twoyear study of functional restoration in industrial low back injury. JAMA, 1987;258:17631767. O’Sullivan P, Twomey L, Allison G 1997. Evaluation of specific stabilizing exercise in the treatment of chronic low back pain with radiologic diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolysthesis. Spine 24:2959-2967. Reid S, Haugh LD, Hazard RG, Tripathi M. Occupational low back pain: recovery curves and factors associated with disability. J Occup Rehab 7 (1997) 1-14. Sachs BL, David JF, Olimpio D, et al. Spinal rehabilitation by work tolerance based on objective physical capacity assessment of dysfunction. Spine 1990;15:1325-1332. Selim AJ, Xinhua SR, Graeme F, Deyo RA, Rogers W, et al.. The importance of radiating leg pain in assessing health outcomes among patients with low back pain. Spine 1998:23:470-474. Shekelle PG, Adams AH, Chassin MR, et al. Spinal manipulation for low-back pain. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:590-8. Spitzer WO, et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on WhiplashAssociated Disorders. Spine 20:8S; 1S-73S, 1995. Timm KE. A randomized-control study of active and passive treatments for chronic low back pain following L5 laminectomy. JOSPT 1994;20:276-286. Triano J, McGregor M, et al. Manipulative therapy vs education programs in chronic low back pain. Spine 20:948-954, 1995. Troup JDG, Martin JW, Lloyd DCEF. Back pain in industry: a prospective survey. Spine 1981;6:61-9. van den Hoogen HJM, Koes BW, Deville W, van Eijk JTM, Bouter LM. The prognosis of low back pain in general practice. Spine 1997;22:1515-1521. van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. A cost of illness study of back pain in The 43 Netherlands. Pain 62 (1995) 233-240. Von Korff M, Deyo RA, Cherkin D, Barlow W. Back pain in primary care: Outcomes at 1 year. Spine 1993;18:855-62. Von Korff M, Saunders K. The course of back pain in primary care. Spine 1996;21:28332839. Waddell G Feder G, McIntosh A, Lewis M, Hutchinson A (1996) Low Back Pain Evidence Review. London: Royal College of General Practitioners. 44