ending the World - Richmond Hill United Church

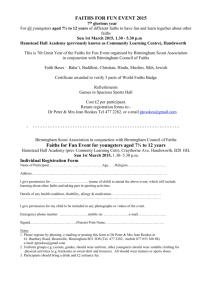

advertisement

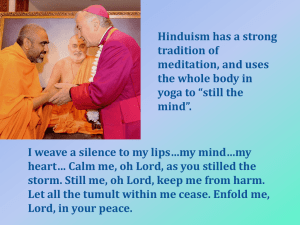

Mending the World Isaiah 42:1-9 Most of you know that I was born and raised on a farm in mid-Western Ontario, that I attended a small country church as a child and teen-ager, that I went to elementary school in a one-room country schoolhouse, and a high school of about 250 students in the closest nearby town of Durham.....all of this in a small-c conservative, homogeneous context that didn’t tolerate let alone welcome “difference” or “variety”. I guess you could say that, for the first 18 years of my life, I lived in a pretty sheltered environment. In my elementary school of about 25 students, for example, there was one family that was “different” – they were Catholic! I remember the fuss in my family when my cousin married a Catholic and my relatives were confronted for the first time in their lives with the enormous spectre of attending a wedding in a Catholic church. ”What do you wear on your head?” seemed to be the biggest issue, at least for the women. ”When do you stand or kneel?” was another. And, more significantly, “Would our Protestant forebears roll over in their graves?” and “Would anything ever been the same in our lives again?”. It all seems so petty, now. In the nearby town of Hanover where we went to do most of our shopping, and for piano lessons, there was one Jewish family who operated a men’s clothing store and they, of course, were a total mystery to us! Much of what I learned in church about other faiths – [which wasn’t very much at all] - I learned from the hymns we sang. And they certainly didn’t paint a very pretty picture of the spiritual prognosis or the “final destination” (if you get my drift!) of anyone who was not Christian. Probably the most familiar would be the 4th verse of the hymn “Mothers of Salem”. We all sang this as kids in Sunday School: “O soon may the heathen of every tribe and nation fulfil Thy blessed word and cast their idols all away”. And we sang it lustily, with big smiles on our faces! Nice! Or the 3rd verse of the hymn “Fling Out the Banner!”: “Fling out the banner! heathen lands shall see from far the glorious sight, and nations, crowding to be born baptize their spirits in its light”. Remember that? And the 3rd verse of the hymn “From the Eastern Mountains” instructs us to: “Gather in the heathen, who in lands afar ne’er have seen the brightness of Thy guiding star”. 1 All 3 of those hymns were in The United Church “Hymn Book”! The not-so-subtle message was that anything that was different from us had to be changed to be like us (our way being the “right way”, of course); non-Christians had to be converted to Christianity, they had to “see the light”, give up their (at best) “misguided” ways, and become - well - become like us. The mission of the Christian church (not to put too fine a point on it!) was to “kick heathen butt” - “heathen” including anything and everything that was different from us or unfamiliar to us. What I did not know then, in my little corner of the world, was that The United Church of Canada – [in contrast to this] - had actually said some pretty positive and progressive things about the relationship of different faiths. As far back as 1936, General Council approved a statement that said, in part, that “the Christian should exhibit toleration, a genuine desire to understand and appreciate, and a willingness to cooperate, where cooperation is possible, with sincere men and women of other faiths”. A 1966 statement said that “the Church should recognize that God is creatively and redemptively at work in the religious life of all mankind”. More recently, in the late 90’s and early 2000’s, the United Church promoted studies and made statements about our relationship with Judaism, with Islam and with First Nations. It’s very easy – too easy, really! - to come up with all kinds of quotes from the Bible that suggest that Jesus is the only way to God - just as it’s easy to come up with quotes from the Bible that condone slavery and the submission of women, and condemn homosexuality. But there is another - over-arching - scriptural message that speaks of God as Creator of the whole world, including all of its creatures and all of its people. God’s Spirit gives life to all Creation. The Spirit “blows where it chooses”, and we dare not confine that “touch of the Spirit” to any one group of people - to any one nation - to any one religious practice. God’s covenant with Noah explicitly identifies “the whole world” as the object of God’s concern. God’s covenant is described (in Genesis) as “the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of all flesh that is on the earth”. The great prophets of Israel were convinced that God cared about every aspect of the life of the world, especially the political and economic causes of hurt and oppression. Isaiah, in our reading this morning combines his universalism and particularism in such a way as to deepen and reinforce both when he says that God has given God’s servant “as a light to the nations” (a light to the Gentiles, in older versions). The visit of the Magi to the Christ-child (one of the traditional Epiphany stories), also points to the universal nature of God’s love, the Magi being foreigners - Gentiles from far away, most likely pagans. Jesus adopts the biblical vision of the prophets, and consistently acknowledges that doing the will of God - [living in the Realm of God] - is the only thing that really 2 matters. Saying “Lord, Lord”, or claiming a particular religious heritage or privilege is no substitute for faithful action, Jesus says. Many of the gospel stories underline this conviction that the breadth of God’s concern is universal. For example, the healing of the Centurion’s servant.....the story of the Good Samaritan.....Jesus’ encounter with the woman at the well. In all of these stories, we see that the presence and power of God’s Spirit is not restricted to Jesus and his followers, or to the church they will build in his name. Jesus instructs the community of his followers to seek and to celebrate the presence and power of God’s Spirit wherever and whenever it may be found! My world today is very different from my world of 60 years ago. Today, I live as we all do - smack dab in the middle of one of the most cosmopolitan places in the world. Ignorance may have been a legitimate excuse when I sang those hymns as a child, but we can no longer claim that “we just don’t know anybody who is not a Christian”; we can no longer claim that “this is a Christian nation and everybody who lives here should be Christian”. And so interfaith relations, interfaith dialogue, has taken on a whole new meaning and urgency. Over the years, scholars and authors have come up with all kinds of ways of describing the relationship among different religious faiths. A while back, I picked up a copy of a book called “The Intra-Religious Dialogue” by Raimon Panikkar, who was born into two major religious traditions Christian and Hindu. In it, Panikkar outlines a number of what he variously calls “attitudes, postures, metaphors, models or paradigms” to describe the relationships or encounters among different faiths. These models make no judgment or comment about “right/wrong”, “better/worse”, “superior/inferior”. They are simply ways of describing the relationship among the worlds’ religions practices, traditions and peoples. One model is what he calls “The Physical Model: The Rainbow”. The different religious traditions of humankind are seen, in this model, as the almost infinite number of colours that appear once “the divine” - [or simply “the white light of reality”] - falls on the prism of human experience. It diffracts into innumerable traditions, spiritualities and practices. Through any particular colour – [any particular religion] - one can reach the source of the light. If two colours mix, they may produce another, as in Panikkar’s own Hindu/Christian experience. One thing about this “rainbow metaphor” is that it offers a way to say that the variety of religions are a part of the beauty and the richness of human life, because it is only the entire rainbow – [and not any one colour alone] - that provides a complete picture of the true religious dimension of humankind. Another model is “The Geographical Model: The Ways to the Mountain Peak”. It seems to be a part of human nature to strive for what could be called “completion” or 3 “integration”, “connection”, some ultimate “goal”. Some people have called that God or salvation, shalom, happiness, heaven, security, and so on. One way of describing this is that we are pilgrims, moving toward the “summit (of life)”. In this model, a religious tradition or practice is one way - one path - that leads to the peak of that mountain. Different faiths become the different paths that climb one mountain. The Rainbow Model.....the Mountain Model.....or how about “The Mystical Model: Silence”. In the context of inter-faith relations, when Panikkar talks about “silence”, he’s not talking about a silence of indifference, or a silence of skepticism. He’s talking about a silence of respect - a silence for listening - a silence for just being, without ‘judging’ or ‘measuring’ or ‘competing’. Mystics of all types and all times have embraced this model. They tell us that “every word is only a translation” - a translation of ‘truth’, or ‘meaning’. So the most appropriate response may simply be an accepting silence. In a way, I realize that I’m “preaching to the choir” here. The United Church “Identity Study” that many of us participated in last year, showed that 88% of United Church people “somewhat or strongly agree” that “Christianity is one path among many”. And as for RHUC responses, 92% agreed! The aim of interfaith dialogue is not to “win over” the other, it is not to come to a “total agreement” on everything, and it is certainly not to create a new “universal religion”. The goal of inter-faith dialogue - (whatever model or metaphor or paradigm you use to describe that experience) - is about understanding, it’s about listening, it’s about “mending the world”, about building a world where love lives. When I think about God in anthropomorphic terms – [with human characteristics and attributes] - I think that God must cry when God sees the way we’ve separated ourselves and divided ourselves and built walls to keep one another either in or out. And so I end with this writing, “To Weavers Everywhere” by Marchene Rienstra - from the United Church document “Mending the World”. It uses the imagery of the Weaver to express both the sadness and the hope of our world: God sits weeping. The beautiful creation tapestry she wove with such joy is mutilated, torn into shreds, reduced to rags its beauty fragmented by force. God sits weeping. But look! She is gathering up the shreds to weave something new. 4 She gathers our shreds of sorrow the pain, the tears, the frustration caused by cruelty, crushing, ignoring, violating, killing. She gathers the rags of hard work attempts at advocacy initiatives for peace protests against injustice all the seemingly little and weak words and deeds offered sacrificially in hope, in faith, in love. And look! She is weaving them all with golden threads of Jubilation into a new tapestry, a creation richer, more beautiful than the old one was! God sits weaving patiently, persistently with a smile that radiates like a rainbow on her tear-streaked face. And she invites us not only to keep offering her the shreds and rags of our suffering and our work But even more to take our place beside Her at the Jubilee Loom and weave with Her the Tapestry of the new Creation. Thanks be to God! Warren McDougall Richmond Hill United Church March 11, 2012 Lent III 5