Why Women Don`t Choose Computing

advertisement

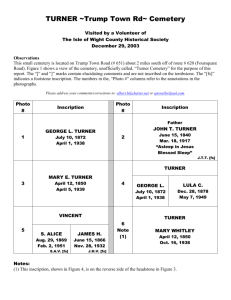

Social Diversity and Difference Seminar Series, Birmingham 27/4/2005 Why Women Don’t Choose Computing Eva Turner, University of East London. e.turner@uel.ac.uk The first seminar in this series concentrated on how students choose whether and when to enter HE, what their motivation and aspirations are, and whether their perceived middle or working class background affects their choice of university. The advertised topic for this morning’s session is: What have we learned about the impact of gender, ethnicity and socio-economic background on choice of both institution and discipline at the pre-entry stage of the student life cycle? and this afternoon’s session is about: How do pre- and post-1992 institutions and individual departments prepare for a new intake of students from differing socio-economic, cultural and ethnic backgrounds? What impact does this have on pre-entry student choice? My contribution to this seminar will reflect my research specialism in gender and computing technology. I will talk first about my own experience as a woman lecturer teaching women students post-1992 “new” university computer science, and then in more general terms about the issues raised in this morning’s session. I will be looking particularly at the external influences, both industrial and cultural, that may have a bearing on course and subject choice. “New” University Computer Science In 1990 I was asked to organise and run an FSC funded IT course for women returners. It was a one year course equivalent to the first year of a degree in Information Technology, open to women over the age of 25 (later 21), which ran successfully for 5 years. It gave around 180 women not only practical skills in computing, but also valuable experience of higher education, and increased confidence and selfesteem. Most of the women came on to the course because they wanted to return to work after a career break, and felt they needed an update in new technology. All of them lived locally. Though the catchment area of the university includes large black and Asian communities, most of the students were white and over 30 years old. 32% had no qualifications or were educated to “O” level or equivalent, and 38% were educated to “A” level or equivalent. 26% were single mothers. About a third of these women proceeded to Higher Education, and a further quarter opted for further non-degree training. Responses to the post-course questionnaire for the first 3 years (64 = 66%) showed that at least 13 women went on to Information Technology degrees, 5 obtained employment in the Computing Industry, and 12 worked as highly skilled IT specialists. In those days a number of ESF women-only courses ran all over the country. Most offered only basic, low level IT literacy, and were designed to ensure a lower clerical level of employment. My course aimed at a high level of technical literacy, offering the choice of either continuing in technical education or obtaining more skilled employment. While the “old” polytechnic had been committed to supporting this course when the ESF money ran out, the “new” university withdrew this support, interpreting women only course as contravening their equal opportunities policy. They did not provide a forum for discussion on equal opportunities in a climate of rapidly declining numbers of women students (particularly mature women students) who choose to study computer science in a department with a very few women lecturers. The general feeling among academic staff from the “old” polytechnics was that they were primarily committed to teaching, working at predominantly teaching institutions. Much of the 1980s was spent modularising the degrees, opening them to a wider student body. The student-centred approach, while not always underpinned by an awareness of the “political correctness” demanded today, was nevertheless effective in drawing students from a wide range of disadvantaged and minority groups, and encouraging mature women into education. Except, that is, in the field of technology. This remained male dominated and effectively closed to women staff and women students. The transformation of polytechnics into universities has, in my experience, led to a substantial emphasis being placed on departments becoming research active in a way acceptable to RAE. This led to a withdrawal of support for the broad modular approach in favour of more narrowly focused computer science degrees. A largescale early retirement scheme was put in place to weed out staff not research active, and over a period of time this resulted in an environment which closely resembled the traditional computer science departments of the “old” universities. This policy made computer science even less attractive to women, both students and potential members of staff. The self-image of these new departments now reflected the general public and the “old” universities perception of computer science as mathematical, techie and nerdy. At the same time, however, in the context of a booming computer industry it was seen by large numbers of students as a stepping stone to a highly lucrative career. As computer science grew to be the biggest department at many universities, women did not choose to study (or work) there. They chose Business Information Systems and Information Technology related degree courses instead. And as my own course came to an end, the powers that be saw no value in supporting future courses specifically aimed at getting more women into computing. There were more than enough male applicants to choose from. Why women don’t choose computing The number of women in computing education is extremely low. Various studies have come up with figures of between 4 and 18%. The DTI’s own statistics (DTI 2003) suggest 20%, but I believe a close examination of completed female graduations would expose this as a considerable over-estimate. There are many reasons why women do not like to study computer science. A range of investigations has been published on this topic, and a range of conclusions has been drawn, many of them far from satisfactory. For example, a number of papers, including some of my own early efforts, argue that female role models will set an example to girls choosing a specific area of study. But according to observed DTI and AWISE activities based on the role model format, it seems this has not been the case, in either Science and Technology in general, or Computing in particular. This phenomenon has been well documented over the last 20 years (Martin et al 2004, Camp 2002, Turner 2001, Mortleman 2004), and it has been argued that the lack of women’s participation in the creation of technology is excluding an important and substantial body of human experience from the process (Suchman 1994’ Adam 1998, Schiebinger 1999 and others). Working conditions and the xpectations the computer industry has of its employees are almost Victorian (e.g. Richardson and Richardson 2001). Unionisation is non-existent, and workers are often expected to be on call 7 days a week. A lack of opportunity for women to return after a career break, gender and race discrimination at the point of entry into the profession (e.g. Turner 1997, 2001), and the male-dominated nature of the working environment (e.g. Webster 1996) have often been blamed for women not choosing to work in the industry. Women are not equally paid for equal work in many industries, and the computing industry is no exception (Martin et al 2004). In fact, the “glass ceiling” in the computer industry is probably lower than in many others. In general, the number of women managers in the industrial West is increasing, but in the computer industry statistics indicate that only 21% of senior managers, and 8% of top managers, are women (Enzine 2004). And according to Martin et al (2004), in the UK alone there are some 50,000 women with degrees in science, engineering and technology (including computing), who are not using their qualifications. Schools and parents both have considerable influence over the way girls choose their future careers (Bleeker 2002), and 50,000 women is a lot of potential mothers whose example could discourage their daughters from entering the fields of science and technology. On the other hand, I myself am a computer scientist, and my daughters are competent computer users, but it seems that neither of them has been inspired by my example to choose computing as a career. They both maintain that IT was the most boring subject they studied at school. Out of many possible reasons for this attitude, I believe that the major one is still the social conditioning we all receive from the age we become susceptible to external influences. Film, television and literature, as well as parents and peer groups, bombard us with messages which we unconsciously absorb in a self-perpetuating cycle. There is a body of research which compares how boys and girls gain a teacher’s attention during interaction with computer technology, and how they co-operate in front of computers. This research also looks at how teachers themselves relate to new technology, and at social stereotyping in education and play activity. From our early years we watch advertisements on our television screens that show cuddly teddy bears and dolls being used by cute little girls voiced over by cute little girls, while technical and combinatorial toys are invariably used by boys voiced over by adult males. In the movies, computer scientists – terrestrial or otherwise – are usually men, or occasionally sexy and not very realistic women. Computer games are typically designed and bought for boys and men, often with stereotypical male content including female actors of Lara Croft type. On the rare occasions when technology is portrayed as female friendly, the advertisers again resort to stereotypes - a microwave oven with internet access, for example, to help in a search for better recipes. In 1998 I published a study of computer advertisements (Turner 1998), based on 3 years of issues of PC World magazine (1993-1996). I analysed all 583 advertisements (repetitions excluded), which promoted computer hardware, software and services using pictures of people or parts of their bodies. Of these, only 83 used pictures of women, and 12 used female hands, and as I will demonstrate, there were substantial differences in the way men and women were portrayed. With only one exception, the women either did not interact with the computer technology at all – they are seen using a telephone, or appeared as decorative or sexual objects accompanying the technology. Most of them looked directly into the camera, or appeared confused. Men, on the other hand, were nearly always shown as fully engaged with the technology, rarely looking into the camera. When they did, they were usually named as real people in positions of authority, and when used as decorative objects, their bodies typically represented power. In my opinion, this research exposed a computer industry whose attitude towards the women in its advertising campaigns was fundamentally irresponsible. Nor, as it happened, did any of these advertisements pay heed to people with special needs, or use black or Asian people in any positive way. The message these advertisements sent to the general public was that women are not confident with technology, and have no status or power around computers. The industry was neither advertising nor selling the computers to women, thus asserting that both technological know-how and purchasing power were in the hands of men. Since then I have collected advertisements from other sources to see if the computing industry (which is now making noises about underrepresentation of women in the creation of the technology) is showing any signs of getting its act together. And as you will see, the message it’s sending to its consumers has not changed a great deal in the last 12 years..... Conclusion Using advertisements is only one way to illustrate the concealed social messages we allow to be sent to women about themselves and their relationship to computers. We can also learn valuable lessons from the behaviour of teachers in both schools and universities (Turner 2005), the nature of computer games, the dynamics of family and work relationships, the position of women in the computer industry and education (e.g. Webster 1996, Camp 1997, Roberts 1997, Turner 2002), and university material advertising computer courses (Grundy 2000). As a society, we need to acquire the political will to address the issue of equal opportunities for women to choose Computing as an area of study and as a potential career. References Bleeker, M. (2002), ‘Parents' Influence on Math and Science Career Plans of their Adolescent Children’, Poster Presentation for Research in Adolescence, New Orleans, LA Camp, T. (October 1997), The Incredible Shrinking Pipeline, Communication of the ACM Journal, pp 103-110 DTI Higher Education Statistics Summary (2003) http://www2.set4women.gov.uk/set4women/statistics/04_index.htm [27 March 2005] Enzine (2004) Women in Management, http://www.softworkscomputing.com/feb04_ezine/dload_women_in_mgmt.html [27 March 2005] Grundy, F. (2000), 'University Prospectuses for Computing: Is There a Hidden Message for Women?' Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering 6(4) pp. 331-348 Martin, U., Liff, S., Dutton, W., Light, A. (2004), Rocket science or social science? Involving women in the creation of computing, Oxford Internet Institute, Oxford Roberts, P. (1997), Androgynous Women in Computing: A Perfect Match, in Lander R and Adam A (eds) Women in Computing, England: Intellect Turner, E. (1998), Advertising Knowledge: The Role of Women and Minorities in Advertising Computers, in AISB Quarterly, summer 1998 No 100, The Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and the Simulation of Behaviour, pp 37-52 Turner, E. (2002), Gendered Future of Computer Profession, Establishing and Ethical Obligation on the Computer Educators, in Alvarez, I. et al (eds) The Transformation of Organisations in the Information Age, proceedings of the 6th International Conference ETHICOMP2002, Universidade Lusiada de Lisbon, pp 711-722 Turner, E (2005), Teaching Gender Inclusive Computer Ethics, paper presented at 3rd European Symposium on Gender and ICT – Gender and ICT – Working for Change, Manchester Webster, J., (1996), Shaping Women's Work: Gender, Employment and Information Technology, Longman