Focus of the lesson: SOL writing domains and definitions—

advertisement

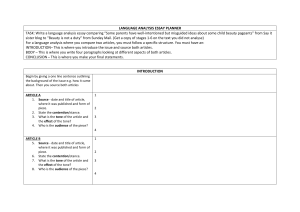

MIDDLE SCHOOL ENGLISH INSTRUCTION: Unit 6, Lesson 3 1 Focus of the lesson: SOL writing domains and definitions— written expression; revision This lesson will focus on the Written Expression domain. SOL Writing: Domains and Features Written Expression This domain is focused on during the drafting and revising stages of the writing process. Features: Information Voice Tone Rhythm The Written Expression domain includes choice of information that clearly communicates the point of the writing; authentic voice; purposeful tone; and structurally varied, effective sentences that help to create a flow to the writing. 1. Information The paper contains a purposefully crafted message that the reader remembers, primarily because its precise information and vocabulary resonate as images in the reader’s mind. Highly specific word choice and information also create tone in the writing and enhance the writer’s voice. 2. Voice In writing, voice is the way your writing 'sounds' on the page. It has to do with the way you write, the tone you take--friendly, formal, chatty, distant--the words you choose--everyday words or high-brow language--the pattern of your sentences, and the way these things fit in--or not--with the personality of the narrator character and the style of your story. Read the article on pp. 2-4 of this lesson that explains the concept of a writer’s “voice.” MIDDLE SCHOOL ENGLISH INSTRUCTION: Unit 6, Lesson 3 2 Finding Your Voice Susan J. Letham Novice writers tend to feel awed by the concept of "voice." Once you understand what writers mean by voice, it becomes easier to grasp. You wouldn't mistake Oprah's voice for Britney Spears’, even if you couldn't see their faces, would you? And if I were to give you a text to read, you wouldn't confuse a mobster’s with that of a Washington lawyer. Not only do they sound different, they also use different kinds of language: words, tone, sentences, forms of address. Here are three voice examples: Example 1: I love the heady cruelty of spring. The cloud shows in the first weeks of the season are wonderfully adolescent: "I'm happy!" "I'm mad, I'm brooding." "I'm happy--now I'm going to cry ..." The skies and the weather toy with us, refusing to let us settle back down into the steady sleepy days and nights of winter. Example 2: I believe I have some idea of how the refugee feels, or the immigrant. Once, I was thus, or nearly so. ... And all the while I carried around inside me an elsewhere, a place of which I could not speak because no one would know what I was talking about. I was a displaced person, of a kind, in the jargon of the day. And displaced persons are displaced not just in space but in time; they have been cut off from their own pasts. ... If you cannot revisit your own origins-reach out and touch them from time to time--you are for ever in some crucial sense untethered. Example 3: Privacy in the workplace is one of the more troubling personal and professional issues of our time. But privacy cannot be adequately addressed without considering a basic foundation of ethics. We cannot reach a meaningful normative conclusion about workplace privacy rights and obligations without a fundamental and common understanding of the ethical basis of justice and a thorough understanding of individual and organizational concerns and motivations. Different backgrounds and distinguishable voices - Do you think the examples were written by the same person? Of course not. Anne Lamotte (example 1) is a contemporary US Writer and diarist. Penelope Lively (example 2,) is a British author who spent her childhood in Cairo in the 1940s. Laura Hartman (example 3) is an academic who writes about ethics and technology. They are people with different backgrounds and distinguishable voices. MIDDLE SCHOOL ENGLISH INSTRUCTION: Unit 6, Lesson 3 3 Voice is the way your words "sound" on the page In writing, voice is the way your writing 'sounds' on the page. It has to do with the way you write, the tone you take--friendly, formal, chatty, distant--the words you choose--everyday words or high-brow language--the pattern of your sentences, and the way these things fit in--or not-- with the personality of the narrator character and the style of your story. The voice I'm using to write this is friendly, familiar, and direct, at least I hope it is. I'm writing more or less the way I would speak if we were chatting face-to-face. When I write poetry, fiction, or social policy articles, my voice is quite different. I don't talk straight to my reader as I'm doing to you, I move back a step, become more distant, choose other words and different sentence structures. You might be surprised to know how many beginning writers write out of character, that is, they choose the wrong voice and tone for the purpose they have in mind. Your New England preppie won't chew on her words like someone with a Texas drawl or talk sexy, like a Detroit hooker. A Hickville street sweeper is unlikely to speak like a Harvard graduate, at least not unless he really is a Harvard graduate... but that would be story, not voice. Voice is a reflection of experience Voice is a reflection of how your character experiences the world of your story. Invest time in developing your figures and getting to know their background. When you've done that, tell your story out loud, as if the characters in your story were speaking. Let your characters tell you the story, listen carefully to how they do it, then start writing your story down. If you can 'hear' your characters, it's likely that you'll get the voice of your story right. How to develop your voice Write as much as possible. Keep a journal. Imagine you are writing your journal for a friend, perhaps in letter style. Write about your day, the things you see and experience, the thoughts that go through your head. Watch the news or read a newspaper and write your thoughts on current events. Writing about your views is good voice practice, because it forces you to think of new things to say and new ways to say them. We don't stop to think too much as we write letters, we don't weight up every word--we tell the story. That's exactly what you need to do when you write your drafts. When you start to worry about the way you're going to sound, you quickly lose your voice. Ask friends to describe your style Once you have a stock of personal writing, ask a friend to read it and tell you how you come across on the page. - Is your personal writing literary? funny? romantic? poetic? factual? upbeat? depressing? straightforward? flowery? How do you sound? - Do you write your mind? Express opinions? Or are your words over-polite and politically correct? Writers get to call intimate interpersonal relations 'sex' and digging implements 'spades.' - Is it stilted? Does it flow? Do you sound like YOU? - Does your writing have a rhythm? - Do all your sentences sound the same? Are they varied? - Do you have 'favorite' words and phrases that you repeat often? If so, which ones? Can you find alternatives? We have to go deep inside to find our real voices, the ones that hide beneath the social veneer, and that means finding out who we are and what we think about the world. It's important that you get to know your MIDDLE SCHOOL ENGLISH INSTRUCTION: Unit 6, Lesson 3 4 natural voice so you can stay in style, and so you can adapt to fit your characters in the right way. A long, long letter to your reader When you move from your journal into your story, think of your manuscript as a long, long letter to your reader, and remember that we rarely have problems writing letters and journals. It takes time and a lot of writing to develop a voice, and impatient writers love to skip that part of the process. But writing before you're ready won't cut it in most cases. You run the danger of having no real voice to speak of (or with.) 3. Tone Tone is the writer’s attitude toward the reader and toward the subject of the writing. For example, someone writing about the tragic death of a father would probably adopt a melancholy or angry tone, while someone writing about the escapades of Paris Hilton might write sarcastically. 4. Rhythm Rhythm in writing results primarily from well-constructed sentences with varied structures. Click on the link below for a discussion of rhythm, as well as a good and bad example of rhythm. Writing with Rhythm _______________________________________ ACTIVITY 6.3.1 Now you are ready to begin revising your paper. Initially, you will revise for relevance and specificity of information and details. Read the article on the next page that provides information about revision strategies. MIDDLE SCHOOL ENGLISH INSTRUCTION: Unit 6, Lesson 3 5 REVISION STRATEGIES Global Revision Always begin the revision process by turning your attention to the larger, or global, elements of writing: focus and organization. If you begin by making sentence level changes, or local revisions, you run the risk of overlooking or ignoring the more serious issues. In addition, you may find that the sentence you spent twenty minutes rewording into beautiful and fluid prose isn't really relevant to your thesis statement and you have to delete it after all. When you begin the revision process by looking closely and honestly at the overall focus and organization of the paper, then you save yourself a lot of needless proofreading. Global revision does not mean simply moving paragraphs. Revising can be difficult and may call for substantial rewriting of the paper. You might discover, for example, that your central idea is much too broad for the length of your essay. When you narrow the central idea, you may then find that you need to cut out paragraphs that are no longer relevant to your point and that you need to expand on other sections instead. Sharpening the Focus A draft is clearly focused when it concentrates the reader's attention on one idea without straying from it. You can test whether or not your paper is well-focused by mapping the paper. In the margins, list the main points of each paragraph. When you are finished, make sure that each of these main points is relevant to your central idea. If the information seems to stray, you must decide whether your whether some information in the body of the paper needs to be deleted or reworked to be relevant to your central idea. You can sharpen the focus of a draft by deleting any information that seems to stray from your main point. Adding Text When you find a section that seems to need development, perhaps because there are not enough examples, you will need to return for a moment to the beginning of the writing process. List specifics, brainstorm ideas, and review your prewriting for relevant support for your central idea. Think about what you are assuming the reader knows. Have you omitted important information? Deleting Text Look for paragraphs and sentences that seem repetitive. Can they be deleted or combined with other sections? Have you strayed from your point or included information and details that are interesting but not necessary? MIDDLE SCHOOL ENGLISH INSTRUCTION: Unit 6, Lesson 3 6 You can access an important revision resource by clicking on the link below. Show, don't tell: THE FIRST RULE OF WRITING After reviewing your information and details and making additions, deletions, and alterations as necessary, you are ready to move on to SENTENCE LEVEL REVISION in Lesson 4.