Ecological Reserves and Protected Areas: The

advertisement

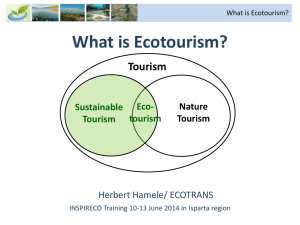

Ecological Reserves and Protected Areas: The Challenge of Ecotourism by Geoffrey Wall February 1993 Prepared for preentation at Seminar on the Environment of the Academic and Scientific Community of Mexico, National Association of Mexican Universities and Inter-American Organization for Higher Education, Toluca, Mexico, February 1993. Abstract Proponents of ecological reserves and protected areas, particularly from the western world, often argue for the designation of large areas of land for preservation purposes. Thus, for example, IUCN has suggested that national parks, if they are to receive international recognition, should be large in size, with minimal human presence, and managed by the highest authority in the country. This has proven to be an unobtainable ideal in many countries with long histories of settlement and growing pressures of population upon resources. Thus, compromises have been struck with the promulgation of biosphere reserves, wilderness areas, heritage rivers and other such innovative categories of land designation which acknowledge mixed and multiple uses of resources. The tension between preservation of ecological integrity and use for tourism and recreation has long been a dilemma facing managers of such reserves. In recent years, proponents of ecotourism have suggested that this seemingly new activity may be both ecologically benign and economically profitable and thus may contribute to the resolution of the dilemma. However, a full consideration of the environmental, economic and social consequences of ecotourism leads to the conclusion that much ecotourism may be little more than "old wine in new bottles" and raises fundamental questions concerning the forms which tourism might take if it is to be both ecologically sustainable, culturally sensitive and economically viable. Introduction Proponents of ecological reserves and protected areas, particularly from the western world, often argue for the designation of large areas of land for preservation purposes. Thus, for example, IUCN has suggested that national parks, if they are to receive international recognition, should be large in size, with minimal human presence, and managed by the highest authority in the country. This has proven to be an unobtainable ideal in many countries with long histories of settlement and growing pressures of population upon resources. Thus, compromises have been struck with the promulgation of biosphere reserves, wilderness areas, heritage rivers and other such innovative categories of land designation which acknowledge mixed and multiple uses of resources. The tension between preservation of ecological integrity and use for tourism and recreation has long been a dilemma facing managers of such reserves. In recent years, proponents of ecotourism have suggested that this seemingly new activity may be both ecologically benign and economically profitable and thus may contribute to the resolution of the dilemma. However, a full consideration of the environmental, economic and social consequences of ecotourism leads to the conclusion that much ecotourism may be little more than "old wine in new bottles" and raises fundamental questions concerning the forms which tourism might take if it to be both ecologically sustainable, culturally sensitive and economically viable. The Nature of Ecotourism The terminology used to describe various forms of tourism is diverse, imprecise, and has expanded rapidly in recent decades. A wide variety of adjectives have been used to qualify tourism and to indicate a concern for particular manifestations or types of tourism. Examples include: green, scientific, appropriate, alternative, responsible, adventure, sustainable, nature.... The list is a long one. Ecotourism is a term which has recently been added to the list. It is not distict from many of the other types of tourism which have been mentioned, contributing further to the confusion. A review of the literature on ecotourism suggests that ecotourism is usually defined on the basis of one or more of three criteria: the characteristics of the destination, the motivations of participants, and the organizational characteristics of the trip. Each of these will be considered in turn. Most commonly, either explicitly or implicitly, ecotourism is defined on the basis of the characteristics of the destination. Ecotourism is usually used to refer to tourism which takes place in relatively natural settings or is directed at specific components of such settings such as rare or endangered species of plants or animals. Such locations are often at considerable distance from the areas of demand, the former often being in countries of the South whereas the ecotourists usually originate in the North. However, this need not be the case and, for example, many Canadian users of Canadian national parks may be regarded as ecotourists. Remote locations also may be the homes of distinctive societies as well as interesting natural phenomena and curiosity concerning natural features may be extended to encompass the peoples that live in proximity to them. Thus some definitions of tourism encompass both natural and cultural elements. For example, Lemky (1992), citing Ceballos-Lacurain, has defined ecotourism as: travelling to relatively undisturbed or uncontaminated natural areas with the specific objective of studying, admiring and enjoying the scenery and its wild plants and animals as well as any existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas. Motivations for travel are many and varied and single trips may be multi-purpose. Ecotourists, following the above definition, are usually regarded as those whose main or a major objective is to witness natural areas or phenomena. Of course, ecotourists may make trips of different types with different motivations on other occasions when they are not to be regarded as ecotourists. Thus, a strong case can be made for classifying specific trips rather than specific individuals as being examples of ecotourism. It is also usually assumed that ecotourists engage in non-consumptive activities. Hunters, who also have a strong interest in natural phenomena, are not usually regarded as ecotourists. However, collectors of rocks, fossils or plants, although sometimes frowned upon, may be regarded as ecotourists. Ecotourists may travel as individuals in an independent manner. However, they often travel as part of an organized group on a specialized package tour. In fact, there has been a proliferation of such travel opportunities in recent years. Usually, it is expected that the size of an ecotourism group will be small, at least when compared with some of the groups involved in mass tourism. Sometimes, all the individuals involved in a specific group are considered to be ecotourists, regardless of motivation. The three elements which have been identified constitute some of the more common attributes of ecotourism but the terminology is sufficiently new and used in such a loose way that, for some, it is little more than a marketing concept. Consider the following advertisement for Yakuna Bay, Belize, "The Eco-Tourism market of the future" which will have "an international hotel, an 18 hole championship golf course, a marina and the most perfect beach front imaginable.... "Eco-Tourism" means it will remain exclusive (and) will encourage both residential and tourist investments in Yakuna Bay". (The Globe and Mail, 12 April, 1991). Boo's (1992) definition is much more restrictive. She suggests that ecotourism is not just ecologically-sound travel, but it is an effort to enhance conservation through travel. According to her, ecotourism is nature travel that actually contributes to conservation. The lack of a clear definition means that the word ecotourism conjures up vivid images, but it is evident that the images are not consistent among users. Given the difficulty of defining the term, one can be sympathetic towards the senior official of Mexico's Tourism Secretariat (SECTUR) who, according to Farquharson (1992), said that ecotourism is now 'transcendental` to every decision that his office makes, but he struggles to produce a definition of the term. The State of Knowledge Given the recency of the terminology, although not necessarily of the phenomenon, it should not be surprising that the academic literature published in refereed journals is sparse and scattered but growing. Although useful compendia exist (Boo, 1990), the majority of the literature is to be found in semi-popular outlets and is primarily descriptive, stressing the attributes of sites and, much less frquently, the characteristics of the tourists and the industry. The papers generally possess little conceptual or theoretical content and are more likely to cite references to the ecological than the tourist literature. Authors are often acutely aware of the fragile nature of ecosystems and that "everything is linked to everything else" but commonly ignore the fact that ecotourism involves both ecological and tourism systems. The lack of an abundant rigorous literature on ecotourism means that the following commentary is not based upon a large body of studies specific to the topic. However, it draws upon a wealth of tourism literature which has evolved over the past several decades and which has been summarized elsewhere (Wall and Wright, 1977; Mathieson and Wall, 1982). For convenience, further discussion will be directed under three headings: environment, economics, and socio-cultural consequences. In reality, these components are closely intertwined. For example, money can be spent to clean up the environment, and changes in incomes and employment opportunities have social implications. Thus, the distinction is somewhat artificial but it has the advantage of imposing a structure on a complex situation which encompasses a diversity of manifestations. Environment Proponents of ecotourism often assume that its activities are environmentally benign. This assumption is made because the number of visitors and party sizes are small, and because the visitors are interested in aspects of the environment and are, therefore, assumed to respect natural phenomena. Visitors are encouraged to take only photographs and leave only footprints. However, even footprints make their mark. I was recently told of a nature hike organized by a prominent Ontario naturalists' group. On discovery of a rare orchid, hikers surrounded the plant, bent back adjacent vegetation to take photographs, and trampled the environs so that the micro-climate will likely have been modified, with the result that there must be some uncertainty concerning the ability of the orchid to survive another year. It is ornithologists that take and collect the eggs of rare birds, not ma and pa and the kids! The above examples may appear to be extreme. However, they demonstrate vividly that, like other forms of tourism, ecotourism has its environmental consequences. In fact, there are good reasons for suggesting that ecotourism has the potential to be environmentally disruptive. Four such reasons will be discussed briefly. 1. Ecotourism is usually directed to very special places which may have limited ability to withstand use pressures. The Antactic is an example. Potential visitors are encouraged to go before it is too late. Cynically, it can be suggested that they are being recruited to put the last nails in the coffin! 2. Visitation may also occur at critical times, such as in the mating or breeding seasons. For some species, such as turtles, this may be the most convenient time to see them. To see predators make a kill may be considered a great moment on a safari, "a new oulet for the blood lust once channelled into hunting" (Gray, 1973, 76). This lust frequently undermines the privacy of the animals being observed. Gray (1973, 28) noted that on one occasion tourists in a safari van watched a cheetah stealthily approach its prey for twenty minutes. Immediately prior to the critical point in the cheetah's approach, the vans converged and tourists climbed on the roofs to take photographs. They created such a commotion that the prey, an impala, became startled and ran off. Myers (1975, 6) claimed that the close shadowing of lions by tourists leads to many missed kills with the result that many lion cubs are starving. He also cited occasions when young animals became fatally separated from their mothers because of the erratic behaviour of minibus drivers. This behaviour is often encouraged illegally for drivers are offered large sums of money to break park rules and chase animals. 3. In the absence of information, it is often assumed that relationship between volumes of use and associated impacts is linear. This is unlikely to be the case. In fact, it is more likely to be curvilinear or even step-like. For example, the research of Liddle and his collaborators (for example, Liddle, 1975a and b, 1988, 1989; Liddle and Scorgi, 1980; Liddle and Kay, 1987), which has been conducted in a variety of ecosystems, including sand dunes, tropical forests, temperate grasslands and coral reefs, indicates that most damage is caused at relatively low levels of use, successive increments of use resulting in smaller units of change. Thus, even small numbers of users generate impacts. It is often assumed that the carrying capacity, a "magic number which does not exist" (Wall, 1982) can be approached with impunity and exceeded at peril, but difficulties in identifying it before it has been exceeded as well as recognition that changes occur at all levels of use (cf. the butterfly effect) have encouraged informed researchers and managers to abandon the concept of carrying capacity and turn to alternative concepts such as limits of acceptable change and the recreation opportunity spectrum (Stankey and McCool, 1984; Driver, Brown, Stankey and Gregoire, 1987). 4. Even if the on-site impact is small, the off-site and en route impacts may be substantial. For example, the considerable distances travelled by ecotourists, often by plane, consume large amounts of energy per capita and contribute to global climate change just as much, and perhaps more, than that of the average mass tourist. Thus, the locations visited, the timing of visits, the nature of use-impact relationships and the distances travelled indicate that much ecotourism is very demanding! Is it possible that the impact per capita could be greater for ecotourists than for mass tourists? Economics When asked about ecotourism, in order to be provocative (some might say nasty), I have sometimes replied with a question: Do you mean economically viable tourism? It is contended that if tourism is to be sustainable it must be both economically viable and ecologically sensitive (as well as socio-culturally appropriate). It cannot be denied that a great deal of money is spent by participants in ecotourism. However, a large proportion of this money is spent at the place of origin, primarily to pay for travel, with usually relatively little being spent at the destination. The places which are likely to be of most interest to ecotourists are likely to be relatively remote, with rudimentary infrastructure, and with little for sale except experiences. By definition, it is difficult to spend money in the wilderness! The result is that, with some notable exceptions, the local economic impact of ecotourism is likely to be small. The magnitude of this impact will vary with the type of traveller. For example, Lemky (1992), in a study of ecotourism in the Amazon rain forest of Ecuador, found that, because of smaller leakages, independent travellers have a more positive economic impact than those on organized tours. However, even though sums of money may not be large, it should be acknowledged that their consequences may be substantial when they are injected into economies which are also small. The market for ecotourism is specialized, concentrated in countries of the north, scattered within those countries, and difficult to contact, particularly for small entrepreneurs of a different language and culture located at a considerable distance from the market. The result is that most companies involved in ecotourism have their headquarters in the north and a large proportion of profits are re-patriated. As a relatively new phenomenon and in the absence of sophisticated information on the market, it is unclear how many tourists are likely to become repeat visitors. Certainly, one might expect scientists to return to the areas which they are studying but, in the case of ecotourists of other stripes, the world is their oyster and, having viewed one natural wonder, they may be tempted to witness others elsewhere. Thus, customer loyalty may be difficult to establish among ecotourists with a resulting requirement to find new customers continually. On the other hand, many ecotourism experiences are highly memorable and, as in other types of tourism, word-of-mouth may be a cheap and fruitful source of new clients. The small sizes of groups and the restricted number of visits required to ensure minimal ecological impacts and high quality experiences also ensure that, unless prices are very high, profits will not be large. Similarly, local economies cannot be expected to benefit substantially from a limited number of visitors. The economic imperative of solvency and, if possible, profit will tempt tour operators and destination areas to increase both the sizes and numbers of parties. If groups of ten are alright, why not try groups of twelve, fourteen or even twenty? If the demand exists or can be created it will be difficult to resist taking five or ten parties per year rather than three. Thus, the economic imperative suggests growth in the direction of mass tourism, for economic growth is usually a goal of destination areas and economies of scale are likely to be sought by ecotourism operators. Thus, it has been argued that the structure of the industry militates against local control and, if numbers are kept small, will curtail local economic impacts. Also, too often, ecotourism may be the only economic activity offered to residents, making them vulnerable to the vicissitudes of a volatile industry whose forces are largely beyond their control. On a more positive note, there is evidence that many ecotourists would be prepared to pay substantially more than they do presently to support the conservation of the areas they visit. Many visitors now pay only nominal admission fees to the areas which they visit which, as in the case of Tortuguera National Park, Costa Rica, are insufficient to cover operating costs at current levels of visitation (Lee and Snepenger, 1992). Enhanced cost recovery through higher user charges is a strategy which merits further investigation. Social Consequences According to Butler (1974), the magnitude of social impacts associated with tourism increases with the number of visitors and also reflects the degrees of difference between hosts and guests in such attributes as wealth, race and language. In many ecotourism destinations, the number of visitors is small but so is the number of permanent residents. Furthermore, in many locations, residents of the third and fourth world (Graburn, 1976) are visited by people from the first world. In such circumstances, the potential for social impacts is great. In some cases, in an attempt to preserve environments for ecotourism, traditional resource uses and users have been eliminated thereby depriving local people of their livelihoods. For example, the designation of Tortuguero National Park, Costa Rica, disadvantaged local residents who had been accustomed to hunting and gathering in the area which became the park (Place, 1991). It was hoped that residents would benefit from the growth of tourism and some have but, in the absence of relevant skills (including language and management skills) and capital, and with small numbers of visitors, it is difficult for local residents to play a meaningful part in and benefit substantially from ecotourism. Poor people cannot afford to be conservationists: people with empty stomachs are not much interested in respecting environmental legislation (Farquharson, 1992). Where local people do not receive benefits, they are likely to compete with the tourism industry for the use of scarce natural resources. If ecotourism is to benefit local residents, means must be found to facilitate local participation in the industry. As a minimum, this will require the provision of appropriate training and access to capital. According to Boo (1992), many tour operators and lodge owners have come to realize that having the added dimension of local involvement is appreciated by tourists and also affords a significant marketing opportunity. Discussion It is accepted that the designation of areas as ecological reserves with a single-purpose, preservation mandate is a worthy objective. However, it has been argued that in some places pressures on resources are such that large areas are unlikely to be set aside solely as nature reserves. Rather, as in most national parks and wilderness areas, preservation and use are required to occur within the boundaries of a single designated area. If preservation is to be achieved in such circumstances, it is necessary that compatible land and water uses be permitted, if such can be found. At first sight, ecotourism appears to be one such candidate use. As a recent term which lacks precise definition, ecotourism has been welcomed uncritically by many of its supporters but, it has been argued, ecotourism may not be as benign as some of its advocates appear to believe. It is perhaps surprising that those with an ecological bent, who are aware that everything is related to everything else, and espouse systems approaches and holistic perspectives, appear to have overlooked that, in the context of ecotourism, the ecosystem is linked to a tourism system. In their eagerness to embrace ecotourism, they appear to have been seduced by the "eco" and have apparently overlooked more than two decades of research on tourism. It is contended that if ecotourism is to thrive, then it should be based upon a balanced understanding of both ecosystems and tourism systems. As an example of relevant tourism research, one can suggest the applicability of tourist cycle models to ecotourism. For example, Butler (1980) has suggested that destination areas appear to go through a cycle, similar to the product life-cycle. According to Butler, resort areas undergo an evolutionary cycle of six stages. The first stage, exploration, is characterized by few individual tourists who secure their own travel arrangements. No marked seasonal visitation patterns exist, nor are there facilities designed specifically for tourists. Contact between local residents and tourists is important. In stage two, involvement, a seasonal pattern emerges, local residents increasingly provide facilities and services for visitors, tourists begin to make traval arrangements through agencies and facility operators initiate advertising. During stage three, development, a well-defined tourist market area appears. The now externally-owned facilities employ extensive advertising to attract tourists, as industry control leaves local hands. In stage four, consolidation, rates of growth in tourist arrivals decline. The local economy depends heavily on tourism, and local residents may find themselves excluded from major attractions. Visitor numbers level off during stage five, stagnation. Few new resorts open and the resort's popularity wanes. At this time, the resort area tends to decline as fewer tourists arrive, facilities depreciate in value, and local ownership of tourist facilities increases. The resort may enter rejuvenation through the development of an artificial attraction by exploiting previously untapped resources or through renovation. When rejunenation occurs after the onset of decline, logically it represents a seventh stage (Kermath and Thomas, 1992). Ecotourism appears to have much in common with the early stages of Butler's cycle. Could it be that ecotourism is nothing more than an early stage of tourism development? Is it possible that ecotourism is essentially old wine in new bottles? Just as anthropologists "discovered" interesting peoples, wrote about them, stimulated interest in them, thus encouraging others to visit them and ensuring thereby that they would never be the same again, so pioneers of ecotourism attract attention to natural treasures, thereby increasing the pressures upon them. Perhaps fortunately, ecotourism caters to a small (but expanding) market segment. It has captured the imagination of those with a strong ecological bent and is receiving attention out of all proportion to its significance. There is a possibility that it is diverting attention from very real and pressing environmental problems associated with mass tourism. According to the World Tourism Organization, there are currently 460 million annual international tourist arrivals and the number will rise to 600 million by the year 2000. They cannot all be ecotourists! Most will continue to be mass tourists with far-reaching implications for the global environment as the Mediterranean attests. The most important environmental challenge facing tourist planners and managers is not to find a means of inserting small numbers of environmentally-aware visitors into pristine environments (although this is certainly a worthy objective); rather it is to devise sustainable forms of mass tourism. Can forms of mass tourism be developed which are environmentally benign? Conclusions Ecotourism is a legitimate activity and it could play an important role in attracting support, both moral and financial, for the preservation of threatened natural areas. It has helped to put environmental issues on the agenda for tourism development and has made some participants in the tourist industry aware of the need to protect the resources upon which their livelihoods depend. Ecotourism may create employment opportunities for communities adjacent to protected areas and is a means of providing environmental education for visitors. However, these potential benefits do not arise automatically. They will only be achieved with appropriate policies and careful planning, including education, training and enhanced access to capital for local residents to facilitate their involvement, for many protected areas were not designated or designed to act as tourist destinations. In such areas, increasing tourism may require managers to redefine the roles of visitors to their areas if growth is to be managed appropriately and adjacent communities are to benefit. Policies for ecotourism might include measures such admission fees or accommodation taxes that ensure the user pays so that money is available to maintain and enhance the resource base, and the requirement that visiting groups must employ the services of a local naturalist and use local products and services during their trips. Fortunately, codes of ethics are veing developed for both visitors and ecotourism companies which, if followed, will ensure that many of the excesses will be removed (Scace, 1993). References Boo, E. 1990. Ecotourism: The Potential and Pitfalls (2 vols). World Wildlife Fund. Washington D.C. Boo, E. 1992. "Tourism and the environment: pitfalls and liabilities of ecotourism development", WTO News, 9, October, 2-4. Butler, R.W. 1974. "Tourism as an agent of social change", Annals of Tourism Research, 2, 100-111. Butler, R.W. 1980. "The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources", The Canadian Geographer, 24, 1, 5-12. Driver, B.L., Brown, P.J., Stankey, G.H. and Gregoire, T.G. 1987. "Toward a behavioral interpretation of recreational engagements, with implications for planning" in Driver, B.L. (ed.) Elements of Outdoor Recreation Planning, University of Michigan Press. Ann Arbor. pp. 9-31. Stankey, G.H. and McCool, S.F. 1984. "Carrying capacity in recreational settings: evolution, appraisal and application",Leisure Sciences, 6, 453-474. World Tourism Organization. 1992. Yearbook of Tourism Statistics. Madrid. About the author: Contact Dr. Geoffrey Wall via the Department of Geography Faculty of Environmental Studies University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada. He can be reached via email at gwall@watserv1.uwaterloo.ca.

![Ecotourism_revision[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005398532_1-116d224f2d342440647524cbb34c0a0a-300x300.png)