About the Planning of the Exhibit

advertisement

{Outer gallery exhibit poster copy}

Puerto Rican History through the Eyes of Others

An Exhibit Curated by Students from the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School

Historia Puertorriqueña a través de los Ojos de Otros

Una Exhibición Curada por los Estudiantes de la Escuela Superior

Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos

Curators:

Maria Cantos,

Warren Elmore,

Sarah Figueroa,

Vincent Figueroa,

Christine Medina,

Maura Medina,

Catalina Mendez,

Ariel Ramos,

Maria Ramos,

Abimael Reillo,

Marisol Roman,

Nicole Williams,

The exhibit was organized, planned, and produced in cooperation with Saúl

Meléndez and Héctor Vázquez, both teachers at the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos

High School, and John Vincler, a graduate assistant at the University of Illinois

Urbana-Champaign’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science.

The exhibit is a product of an ongoing collaboration between the Puerto Rican

Cultural Center in Chicago and the Community Informatics Initiative of the

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Graduate School of Library and

Information Science.

La exhibición fue organizada, planeada y producida en cooperación con Saúl

Meléndez y Héctor Vázquez, ambos maestros de la Escuela Superior Dr. Pedro

Albizu Campos y John Vincler, asistente graduado de la Escuela Graduada de

Bibliotecología y Ciencias de la Información de la Universidad de Illinois en

Urbana-Champaign

La exhibición es producto de una colaboración entre el Centro Cultural

Puertorriqueño en Chicago y la Iniciativa de Informática Comunitaria de la

Escuela Graduada de Bibliotecología y Ciencias de la Información de la

Universidad de Illinois en Urbana-Champaign.

1

{Handout / website copy}

Puerto Rican History through the Eyes of Others

An Exhibit Curated by Students from the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School

Historia Puertorriqueña a través de los Ojos de Otros

Una Exhibición Curada por los Estudiantes de la Escuela Superior

Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos

Curators:

Maria Cantos,

Warren Elmore,

Sarah Figueroa,

Vincent Figueroa,

Christine Medina,

Maura Medina,

Catalina Mendez,

Ariel Ramos,

Maria Ramos,

Abimael Reillo,

Marisol Roman,

Nicole Williams,

The exhibit was organized, planned, and produced in cooperation with Saúl Meléndez and Héctor

Vázquez, both teachers at the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School, and John Vincler, a

graduate assistant in the Community Informatics Initiative of the University of Illinois UrbanaChampaign’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science.

La exhibición fue organizada, planeada y producida en cooperación con Saúl Meléndez y Héctor

Vázquez, ambos maestros de la Escuela Superior Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos y John Vincler,

asistente graduado de la Escuela Graduada de Bibliotecología y Ciencias de la Información de la

Universidad de Illinois en Urbana-Champaign

Descripción de la exhibicion

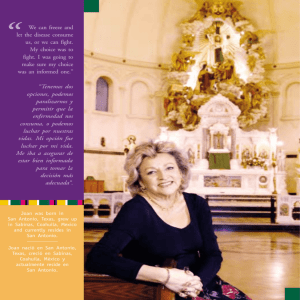

“Puerto Rican History through the Eyes of Others” explores the history of Puerto

Rico over half a millennium, beginning roughly with the arrival of Christopher

Columbus in 1493 to an island called Boriquén by its inhabitants, the Taínos, and

extending through the Spanish-American War of 1898. Through objects written

and drafted mostly by people other than Puerto Ricans, the exhibit looks at and

charts the interests and aims of explorers, travelers, governments, artists,

soldiers, merchants, and historians attracted to Puerto Rico.

2

This first-ever exhibit of Puerto Rican materials held in the Newberry Library’s

collection was planned and organized with student curators from the Dr. Pedro

Albizu Campos High School in Humboldt Park.

La exhibición “Historia Puertorriqueña a través de los Ojos de Otros" explora la

historia de Puerto Rico a través de la mitad de un milenio, empezando con la

llegada de Cristóbal Colón en el 1493 a una isla que sus habitantes, los Taínos,

llamaban Boriquén y extendiéndose hasta la Guerra Hispanoamericana del

1898. A través de objetos escritos y redactados por personas que en su mayoría

no eran puertorriqueñas, la exhibición examina y delinea los intereses y objetivos

de exploradores, viajeros, gobiernos, artistas, soldados, comerciantes, e

historiadores atraídos por Puerto Rico.

Esta primera exhibición de materiales puertorriqueños que forma parte de la

colección de la Biblioteca Newberry fue planeada y organizada por estudiantes

de la Escuela Secundaria Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos localizada en la comunidad

de Humboldt Park.

About the Planning of the Exhibit

In March 2008, students from Saúl Meléndez’s Puerto Rican Cultural and History

class at the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School all received reader’s cards

and were given a behind-the-scenes tour of the climate-controlled building where

the rare and valuable materials in the library are stored. The students began

researching the library’s large collection of Puerto Rican materials ranging from

Spanish manuscripts from the 1600s, original archival photographs, government

documents, resources for tracing family histories, and maps from the

Renaissance to the Spanish-American War. Since March, the student curators

have worked to research and select the final objects shown here. They helped

create the thematic organization, worked to draft the exhibit copy, and then finally

to translate the copy into Spanish as part of their Spanish class taught by Héctor

Vázquez.

The goal of the exhibit, entitled “Puerto Rican History through the Eyes of

Others,” was to allow students to learn how to do research using primary

sources, while gaining first hand experience with museum and library studies.

The exhibit provided the students with an opportunity to engage with history,

while also enabling the students to respond to those that have described and

characterized Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans over the centuries.

The exhibit is a product of an ongoing collaboration between the Puerto Rican

Cultural Center in Chicago and the Community Informatics Initiative of the

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Graduate School of Library and

Information Science.

3

Sobre la Planificación de la exhibición

En marzo de 2008, estudiantes de la clase de historia y cultura puertorriqueña

de Saúl Meléndez en la Escuela Secundaria Doctor Pedro Albizu Campos

visitaron la biblioteca, donde recibieron tarjetas de membresía y participaron de

un recorrido “tras bastidores” alrededor del edificio con control climático en

donde son almacenados estos raros y valiosos materiales. Los estudiantes

tuvieron la oportunidad de observar una colección de materiales antiguos acerca

de Puerto Rico, incluyendo manuscritos españoles de los años 1600, fotografías

originales archivadas, documentos de gobierno, recursos para trazar historias

familiares y varios mapas que abarcan la época desde el Renacimiento hasta la

Guerra Hispanoamericana. Desde marzo, los estudiante han trabajado en la

investigación y selección de los objetos finales mostrados aquí. Ellos ayudaron a

crear la organización temática, redactaron el resumen de la exhibición, y luego

tradujeron el resumen al español como parte de su clase de español enseñada

por Héctor Vázquez.

El objetivo de la exhibición titulada: “Historia Puertorriqueña a través de los Ojos

de Otros" fue contribuir a que los estudiantes aprendieran a conducir

investigaciones historiográficas utilizando fuentes primarias, a la misma vez que

adquirían experiencia en estudios de biblioteca y de museo. La exhibición

también proveyó a los estudiantes la oportunidad de insertarse en la historia,

permitiéndoles así responder a aquellos que han descrito y caracterizado a

Puerto Rico y a los puertorriqueños durante los siglos.

La exhibición es producto de una colaboración entre el Centro Cultural

Puertorriqueño de Chicago y la Iniciativa de Informática Comunitaria de la

Escuela Graduada de Bibliotecología y Ciencias de la Información en la

Universidad de Illinois en Urbana-Champaign.

CASE 1 – Early Puerto Rico Puerto Rico Antiguo

The English translation of Voyages by Jan Huygen van Linschoten (a Dutch

mapmaker) published in London by John Wolfe in 1598 lists Puerto Rico as

“Boriquen,” the Arawak language name the first Puerto Ricans, the Taínos, used

for the island. Already the name for Puerto Rico and its modern capital can be

seen here. The “rich haven” or rich port translates to puerto rico in Spanish, and

“S. Iohn” or Saint John translates to San Juan. This passage relates the story of

how a Taíno chief, here called “Uraioa de Yaguara,” caused a Spaniard to be

held underwater to prove the Spanish were not immortal. Having proven the

Spaniards’ mortality, the Taínos rebelled against the Spanish invaders.

4

As in Linschoten’s Voyages, fellow Dutchman Joannes de Laet’s Historie ofte

Iaerlijck… illustrates that the name Puerto Rico initially referred to the main bay

and port city, while San Juan referred to the island as a whole. The view of

“Porto Rico” shown here illustrates what is known as San Juan today. These

place names, Puerto Rico and San Juan, would soon change places on later

maps to take the meanings they have today.

The remaining books included here illustrate the interest in Puerto Rico from the

time of Christopher Columbus’s second voyage of 1493 through the 19 th century.

In addition to the Dutch and English books above, André Pierre Ledru’s book

describes travels in Puerto Rico (with descriptions of the celebration of Saints’

days shown here in volume two), illustrates the sustained European imperial

interest in the West Indies, and evidences the rise of travel literature as a popular

genre. A Complete historical, chronological, and geographical American atlas,

published in Philadelphia, illustrates the United States’ interest in Puerto Rico

before the Spanish-American War and also shows the persisting use of the

Arawak name for the island even at this late date.

La traducción al inglés del manuscrito Voyages escrito por Jan Huygen van

Linschoten (un creador de mapas holandés) y publicado en Londres por John

Wolfe en 1598 nombra a Puerto Rico como "Boriquen", el nombre para la isla en

lengua arawak utilizado por los primeros puertorriqueños, los taínos. Aquí ya

puede verse el nombre de Puerto Rico y su capital moderna. El "rich haven" o

“rich port” se traduce a Puerto Rico en español, y "S. Iohn "o “Saint John” se

traduce a San Juan. Este pasaje relata la historia de cómo un jefe Taíno, aquí

llamado "Uraioa de Yaguara," sumergió a un español bajo el agua para

demostrar que los españoles no eran inmortales. Después de haber demostrado

su mortalidad, los taínos se rebelaron contra los invasores españoles.

Al igual que en “Voyages” de Linschoten, la publicación “Historie ofte Iaerlijck”

de su compañero holandés Joannes de Laet’s manifiesta que el nombre de

Puerto Rico inicialmente hacía referencia a la bahía y la principal ciudad

portuaria, mientras que San Juan se refería a la isla en su totalidad.. La imagen

de "Porto Rico" mostrada aquí refleja lo que se conoce como San Juan hoy en

día. Estos nombres, Puerto Rico y San Juan, pronto intercambiarían lugares en

los mapas reflejando el significado que tienen actualmente.

El resto de los libros incluidos aquí ilustran el interés en Puerto Rico desde el

segundo viaje de Cristóbal Colón en el 1493 hasta el siglo 19. En adición a los

libros holandeses y ingleses mostrados en esta exhibición, un manuscrito

redactado por André Pierre Ledru describe travesías a través Puerto Rico (con

descripciones de la celebración del día de los Santos mostradas aquí en el

volumen dos), ilustra el sostenido interés imperial europeo en las Indias

Occidentales, y evidencia el auge y popularidad de la literatura de viajes como

género literario. A Complete historical, chronological, and geographical

American, un atlas publicado en Filadelfia, ilustra el interés de los Estados

5

Unidos en Puerto Rico antes de la guerra Hispanoamericana y también muestra

el uso persistente de los nombres arawak de la isla, incluso en esta última fecha.

Object: #1

INSTRUCTIONS: Open to 90-100 degrees.

Discours of voyages East & West Indies

Jan Huygen van Linschoten

London: J. Wolfe, 1598

Call Number: Case folio G 131 .506

Object: #2

INSTRUCTIONS: Conservation to do a minor mend before installation.

Historie ofte Iaerlijck verhael van de verrichtinghen der Geoctroyeerde West-Indische

compagnie

Joannes de Laet

Leyden: Bonaventuer ende Abraham Elsevier, 1644

Call Number: VAULT folio Ayer 1000 L22 1644

Object: #3

A Complete historical, chronological, and geographical American atlas; a guide to the

history of North and South America, and the West Indies: exhibiting an accurate account of the

discovery, settlement, and progress of their various kingdoms, states, provinces, &c. According to

the plan of Le Sage’s Atlas, and intended as a companion to Lavoisne’s improvement of that

celebrated work.

Philadelphia: H.C. Carey and I. Lea, 1822.

Call Number: Greenlee 4891 .C27 1822

Object: #4

INSTRUCTIONS: two volumes: open first to title page second as marked: desc. feast days of

saints celebrated in Puerto Rico

Voyage aux îles de Ténériffe, la Trinité, Saint-Thomas, Sainte-Croix et Porto Ricco

Ledru, André Pierre, 1761-1825.

Paris: A. Bertrand, 1810.

Call Number: Ayer 956 .L47 1810

*

CASE 2 – Slavery, Race, and Ethnic Identity Esclavitud, raza y

Identidad etnica

The Taíno presence and persistence continues to inform the historical memory of

Puerto Rico today, despite the sustained violence and disease brought to these

first Puerto Ricans by the Spanish. In the modern children’s book from 1968

included here—with woodblock illustrations by noted Puerto Rican artist Antonio

Martorell—a Taíno figure is used to illustrate the letter “T” (shown here) and the

Taíno word for Puerto Ricans, Boricua, is used for the letter “B.”

Questions of race and ethnic identity are also addressed in works about Puerto

Rico from both early and later periods. Here a copy of a contract dated April 20,

6

1637 in Seville, Spain before notary Juan Fernando de Ojeda, provides primary

evidence of the slave trade to “New Spain,” the viceroyalty of which Puerto Rico

was a part. Although it is unclear which part of “New Spain” is involved, this

document describes how Domingo de Fonseca, owner and captain of the ship

San Juan Baptista, acknowledges that he must repay a loan of 24,000 reales

made to him by Pedro Ximenez de Enciso so that he can prepare his ship for a

journey to Angola to buy slaves that will be sold in New Spain.

George Dawson Flinter’s book An account of the present state of the island of

Puerto Rico both documents the legacy of slavery in Puerto Rico and illustrates

that slavery was beginning to be viewed as the barbaric and inhumane practice

that it was, though it still persisted in the United States at the time this book was

published. Though racism can be seen in books like this one, it also shows the

spread of the abolitionism movement and its arguments in Europe and the

Americas.

La presencia y persistencia Taína continua informando la memoria histórica

puertorriqueña hoy en día, a pesar de la violencia y enfermedades traídas por

los españoles contra los primeros puertorriqueños. En el libro de niños de 1968

aquí incluido— con ilustraciones de bloque de madera por el renombrado artista

puertorriqueño Antonio Martorell- una figura Taína es utilizada para ilustrar la

letra “T” (aquí mostrado), y la palabra Taíno para “Puertorriqueños”, Boricua, se

usa en vez de la letra “B”.

Cuestiones de raza e identidad étnica también están exploradas en obras sobre

Puerto Rico, tanto de tiempos antiguos como de tiempos contemporáneos. Aquí,

una copia de un contrato con fecha del 20 de abril de 1637 en Sevilla, España,

ante el notario Juan Fernando de Ojeda, proporciona evidencia primaria del

comercio de esclavos a “nueva España,” el virreinato del cuál Puerto Rico

formaba parte. Aunque no está claro qué parte de “nueva España” estaba

implicada en este comercio, este documento describe cómo Domingo de

Fonseca, dueño y capitán de la nave San Juan Baptista, reconoce que debe

compensar un préstamo de 24.000 reales hecho a él por Pedro Ximenez de

Enciso de modo que él pueda preparar su nave para un viaje a Angola para

comprar los esclavos que serán vendidos en nueva España.

El libro de George Dawson Flinter, An account of the present state of the island

of Puerto Rico documenta el legado de la esclavitud en Puerto Rico e ilustra que

la esclavitud ya comenzaba a ser vista como la práctica barbárica e inhumana

que es, aunque todavía persistía como práctica en los Estados Unidos cuando

este libro fue publicado. Aunque el racismo es evidenciado en libros como éste,

también se demuestra la expansión del movimiento abolicionista y los

argumentos de éste tanto en Europa como en América.

Object: #5

ABC de Puerto Rico

7

INSTRUCTIONS: Open to “T” for Taíno page (flagged)

Rubén del Rosario, Isabel Freire de Matos, and illustrated by Antonio Martorell

Sharon, Conn.: Troutman Press, 1968.

Call Number: Wing ZP 983 .T745

Object: #6

Domingo de Fonseca,

Copy of a promissory note regarding a loan to cover expenses related to purchase of African

slaves, [manuscript] 1639 April 1.

Call Number: VAULT box Ayer MS 1089

Object: #7

An account of the present state of the island of Puerto Rico.

George Dawson Flinter

London : Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman, 1834.

Call Number: G 975 .3

*

CASE 3 – Imperialism, Resistance, Ambivalence, Xenophobia

Imperialismo, Resistancia, Ambivilancia, y Xenofobia.

Little is known about this map in the form of a political cartoon, however it

presents a striking and very politically charged image. Uncle Sam seems sinister,

overwhelmed, or both as he lassos the United States’ new acquisitions while

teetering on Cuba with Spain under his arm, all as John Bull looks on from the

British Isles. Does this map attempt to critique the United States’ colonial aims?

Does it give voice to xenophobic anxieties? It is unclear, and it is uncertain if this

map was ever published or reproduced beyond this copy, but it provides a

powerful visual comment on the outcome and aims of the Spanish-American

War, one that is open to many interpretations.

Bailey and Justine Diffie’s explicit critique of the U.S. intervention in Puerto Rico

as one motivated by exploitative and imperial aims provides one potential

reading of the Real Estate for Sale map above. In a 1932 review of the book in

Political Science Quarterly, Elizabeth M. Lynskey concludes, “From these pages

it becomes clear that the island’s alleged favorable balance of trade is highly

fictitious. America is slowly draining Porto Rico of its resources, altering the life of

the island, pushing its population further into misery and contributing little to its

welfare” (458). Supported largely through a study of economics, trade, and the

tariff system, the quotes shown here illustrate the “pledge” of their title, which

they see as one that was never honored and soon no longer acknowledged.

Poco se sabe sobre este mapa en forma de historieta política. No obstante, este

presenta una imagen impactante de carácter político. El tío Sam aparece

siniestro, abrumado, o ambos amarrando las nuevas adquisiciones de los

Estados Unidos y balanceándose en Cuba con España debajo de su brazo, todo

mientras John Bull observa las islas británicas. ¿Acaso intenta este mapa criticar

las intenciones políticas y coloniales de los Estados Unidos? ¿Le da voz a las

8

ansiedades xenófobas? Es confuso, y no se sabe si este mapa fue publicado o

reproducido mas allá de esta copia, pero éste proporciona un poderoso

comentario visual acerca de el resultado y las intenciones políticas de la guerra

hispanoamericana, que aún siguen abiertos a múltiples interpretaciones.

La crítica explícita de Bailey y de Justine Diffie a la intervención de los E.E.U.U.

en Puerto Rico como una motivada por intenciones imperialistas y de

explotación proporciona una posible interpretación del mapa Real Estate for Sale

presentado arriba. En una crítica del libro publicada en 1932 en Political Science

Quaterly, Elizabeth M. Lynskey concluye, “de estas páginas se pone de

manifiesto que la alegada balanza comercial favorable de la isla es altamente

ficticia. América está drenando lentamente a Puerto Rico de sus recursos,

alterando la vida de la isla, empujando su población hacia la miseria y

contribuyendo poco a su bienestar” (458). Apoyado en gran parte por un estudio

de economía, comercio, y el sistema tributario, las cotizaciones demostradas

aquí ilustran el “compromiso” de su título, el cual es considerado como uno que

nunca fue honrado ni reconocido.

Object: #8

INSTRUCTIONS: Mount on backboard. NOTE: 29hx23w

Real estate for sale. Apply at the President's Office, Washington, D. C.

Collage on paper, after 1898

Call Number: Map4F G3690 1899 R3

Object: #9

INSTRUCTIONS: Installation: Opening 90-100 degrees.

Bailey W. Diffie and Justine W. Diffie

Porto Rico: a broken pledge

New York: Vanguard Press (American imperialism series), ca. 1931

Call Number: F 975 .23

*

CASE 4 – Puerto Rico in Pictures Puerto Rico en Fotografías

The two volumes of Our Islands and Their People provide rich illustrations of

Puerto Rico after the Spanish-American War with numerous photographs of both

urban and rural scenes. However, the title provides the first indication of the

condescending tone that is found frequently in the accompanying text. The

islands belong to the United States but are the people of Puerto Rico only an

afterthought?

Without any narrative commentary William Voorhees Judson’s photographs

provide a rare view of panoramas of Puerto Rico, especially the interior of the

island. Judson was an engineer involved in various projects related to road

construction and river and harbor improvements in Puerto Rico, the Midwest,

New York, Texas, and elsewhere. He went to Puerto Rico to build roads after the

9

Spanish-American War and documented his task in pictures now held in the

Newberry Library’s Midwest Manuscript Collections. Most of these pictures show

Comerío a region near the island’s center, which was important for agricultural

production, especially for the production of tobacco.

Los dos volúmenes de Our Islands and Their People proveen ilustraciones de

Puerto Rico después de la guerra hispanoamericana que incluyen numerosas

fotografías de escenas tanto urbanas como rurales. Sin embargo, el título provee

la primera indicación del tono condescendiente que se encuentra con frecuencia

en el texto que lo acompaña. Las islas pertenecen a los Estados Unidos pero,

¿son la población de Puerto Rico solamente un una consideración

insignificante?

Sin ninguna narración, las fotografías de Guillermo Voorhees Judson proveen

una rara vista de panoramas de Puerto Rico, especialmente del interior de la

isla. Judson era un ingeniero envuelto en varios proyectos relacionados con la

construcción de carreteras y la mejoría de puertos y ríos en Puerto Rico, el

Cercano oeste, Nueva York, Texas, y en otras partes. Él fue a Puerto Rico a

construir caminos después de la guerra hispanoamericana y documentó su

trabajo en fotos ahora expuestos en la biblioteca de Newberry. La mayor parte

de estas fotos muestran a Comerío, una región cerca del centro de la isla,

importante para la producción agrícola, especialmente para la producción de

tabaco.

Object: #10

INSTRUCTIONS: Include with second volume closed in case to show title and first volume

opened to image of sugar factory with machinery (marked)

Our islands and their people as seen with camera and pencil;

José de Olivares, Edited and arranged by William S. Bryan, Introduction by Major-General

Joseph Wheeler, Photographs by Walter B. Townsend

St. Louis, New York [etc.] : N.D. Thompson Pub. Co., [1899-1900]

Call Number: Case oversize F970 .O54 1899

Object(s): #11

William Voorhees Judson Papers, 1888-1947

Select Original Photographs of Puerto Rico

Call Number: MMS Judson, Series 5, Box 6, Folders 309 & 310 (as marked)

*

CASE 5 – Before and After the Spanish-American War Antes y

después de la Guerra hispanoamericana

The New Constitution Establishing Self-government—more commonly referred to

as the “Charter of Autonomy”—outlines Puerto Rico’s short-lived conditions of

self-rule as outlined by a Spanish royal decree in 1897. With the American

invasion in 1898, self-rule was never realized for a significant period of time.

10

While not an international treaty, the Charter of Autonomy has since been used

in legal arguments for Puerto Rico’s right to independence. Most notably Pedro

Albizu Campos argued that the United States could not legally be awarded

Puerto Rico at the Treaty of Paris in 1898 without the consent of Puerto Rico’s

Insular Parliament.

Goff’s map of the Spanish-American War charts the events of the war

geographically. { Include the following if allowing the Hermann book: } During

the time of the war personal accounts from the perspective of soldiers in the

United States Army could be read in the popular press. After the war, some of

these accounts were published as popular books. Chicago’s own Carl Sandburg

was among one of these firsthand witnesses. Karl Stephen Herrmann’s account

presented here, shows the undercurrent of racism found in tone and content

which attempts to illustrate the “depravity of the native masses,” describe “the

better classes,” and characterize the “ignorant and childish” views of Puerto

Ricans.

{paragraph break if including the Hermann book} Following the war, U.S. policy in

Puerto Rico was determined in large part by the findings of government officials

like Henry K. Carroll, special commissioner to Puerto Rico, whose Report on the

Island of Porto Rico is shown here. After approximately two years of military rule

under the United States, Puerto Rico was granted only very limited democratic

representation, within a colonial framework that did not afford Puerto Ricans

living in Puerto Rico full constitutional rights (as is seen in the Supreme Court

case Balzac v. Puerto Rico in 1922). Not until the Jones Act of 1917, would

Puerto Ricans become U.S. citizens, and only decades later would Puerto

Ricans elect their own governor and draft their own constitution. The aftereffects

of the recommendations of Carroll and his successors can be seen in Puerto

Rico’s important role recently in the Democratic presidential nomination. Despite

this recent role for Puerto Rico in the campaign process, Puerto Ricans living on

the island are not given a vote in presidential elections, nor the right to selfdetermination.

El New Constitution Establishing Self-Government- designado comúnmente

como la “Carta Autonómica”- establece un gobierno soberano para Puerto Rico

que duró poco tiempo y que fue autorizado por un decreto real español en 1897.

Luego de la invasión americana en 1898, la autodeterminación de Puerto Rico

no fue realizada por un periodo de tiempo significativo. Aunque no fue un tratado

internacional, la carta autonómica se ha utilizado desde entonces en las

discusiones legales acerca del derecho de Puerto Rico a la independencia. En

una de los argumentos mas notables, Pedro Albizu Campos sostuvo que Puerto

Rico no podía ser concedido legalmente a los Estados en el Tratado de París en

1898 sin el consentimiento del parlamento insular de Puerto Rico.

El mapa de Goff de la guerra hispanoamericana traza los acontecimientos de la

guerra geográficamente. Durante la época de la guerra, las experiencias

personales de los soldados se podían leer en la prensa popular. Después de la

11

guerra, algunas de estas historias fueron publicadas como libros populares. El

propio Carl Sandburg de Chicago fue uno de los que vivieron estas experiencias.

La historia de Karl Stephen Herrmann presentada aquí, demuestra la corriente

oculta del racismo encontrada en el tono y el contenido de esta documento que

pretende ilustrar la “depravación de los grupos nativos,” describir “las mejores

clases sociales,” y caracterizar las opiniones “ignorantes e infantiles” de los

puertorriqueños.

Después de la guerra, las políticas públicas de los E.E.U.U. en Puerto Rico

fueron determinadas en gran parte por los hallazgos de oficiales de gobierno

tales como Henry K. Carroll, comisionado especial a Puerto Rico, cuyo Report

on the Island of Porto Rico se muestra aquí. Después de aproximadamente dos

años de régimen militar bajo los Estados Unidos, una representación

democrática muy limitada fue concedida a Puerto Rico, esto dentro de un marco

colonial que no le permitió a los puertorriqueños que vivían en la isla disfrutar de

derechos constitucionales completos (como se ve en el caso del Tribunal

Supremo Balzac v. Puerto Rico en 1922). No es hasta el Acta de Jones de 1917

que los puertorriqueños se hacen ciudadanos de los E.E.U.U., y solamente

décadas después, los puertorriqueños elegirían a su propio gobernador y

elaborarían más adelante su propia constitución. Los efectos de las

recomendaciones de Carroll y de sus sucesores se pueden evidenciar en el

importante papel que jugó Puerto Rico recientemente en la carrera por la

nominación presidencial por el Partido Demócrata. Sin embargo, a pesar de este

importante rol en el proceso de la campaña, los puertorriqueños que viven en la

isla aún no pueden votar en elecciones presidenciales, ni decidir su

autodeterminación.

Object: #12.

New constitution establishing self-government in the islands of Cuba and Porto Rico.

(Authorized translation of the preamble and royal decree of November 25th, 1897, pub. in the

Official gazette of Madrid) With comments by Cuban autonomists on the scope of the plan.

New York : At the Office of "Cuba", 1898.

Call Number: J 5973 .834

Object: #13

Goff's historical map of the Spanish-American War in the West Indies, 1898

Eugenia A. Wheeler Goff

Chicago: Fort Dearborn Pub. Co, 1899

Call Number: sc Map2F G4900 1899 .G6

Object: #14

INSTRUCTIONS: Dirty but otherwise fine. Open to 90 degrees.

Report on the island of Porto Rico; its population, civil government, commerce, industries,

productions, roads, tariff, and currency.

Henry K. Carroll, special commissioner for the United States to Porto Rico.

Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899 [1900]

Call Number: Govt. T 1.17 :P832

Object: #15 *ADD (if possible)*

12

INSTRUCTIONS: Open to chapter describing the people of Puerto Rico (Beginning of Chapter III

– the People of Puerto Rico)

A recent campaign in Puerto Rico by the Independent Regular Brigade under the

command of Brig. General Schwan

Karl Stephen Herrmann

Boston: E.H. Bacon, 1907.

Call Number: F835475 .4

13