Microsoft Word - Lipschutz-War Discipline Imperium - E

Journal of Global Change and Governance• Volume III, Number 1•Winter 2009•ISSN: 1941-8760

CAUSES OF ETHNIC CONFLICT: A CONCEPTUAL

FRAMEWORK

Bojana Blagojevic

Assistant Professor of Political Science, LaGuardia Community College, City

University of New York

The article proposes a multi-dimensional conceptual framework for understanding causes of ethnic conflict, specifically focusing on the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I argue that ethnic conflict occurs when a particular set of factors and conditions converge: a major structural crisis; presence of historical memories of inter-ethnic grievances; institutional factors that promote ethnic intolerance; manipulation of historical memories by political entrepreneurs to evoke emotions such as fear, resentment and hate toward the “other”; and an interethnic competition over resources and rights. The article explores a way in which major ethnic conflict theories: primordialist, institutional, political entrepreneurs and competition over resources, can be combined to explain how the interaction of these factors leads to conflict. The goal of the proposed framework is to depart from simplistic explanations of ethnic conflict and provide a basis for a more comprehensive approach to peacebuilding and post-conflict development strategies in ethnically divided societies .

KEYWORDS

Ethnic Conflict, former Yugoslavia

BIOGRAPHICAL STATEMENT

Bojana Blagojevic received her doctoral degree in Global Affairs from Rutgers University,

New Jersey, in October 2004. The topic of her dissertation was Ethnic Conflict and Post-

Conflict Development: Peacebuilding in Ethnically Divided Societies (case studies included conflicts in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Rwanda and Sri Lanka). Prior to her employment at

LaGuardia, Prof. Blagojevic taught Political Science and Global Studies courses at Rutgers

University in New Jersey. She also worked temporarily as a Conflict Prevention

Specialist/Consultant at the United Nations Development Group Office in New York. Prof.

Blagojevic's research interests include causes of war, conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

©Journal of Global Change and Governance• Division of Global Affairs• Rutgers University http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪2

Introduction

As James Fearon and David Laitin argue, “a good theory of ethnic conflict should be able to explain why, despite the greater tensions, peaceful and cooperative [ethnic] relations are by far more typical outcome than is large scale violence.”

1

According to them, because of the benefits of peace and the costs of inter-ethnic violence, “decentralized institutional

arrangements are likely to arise to moderate problems of interethnic opportunism.” 2

peaceful resolution of inter-ethnic tensions should always prevail as a rational, more beneficial approach, violent ethnic conflicts continue to occur across the world. The global community is haunted by physical and emotional consequences of recent ethnic violence such as the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, genocide in Rwanda and Darfur, and sectarian violence in

Iraq. Continuous examination of the causes of ethnic conflict is necessary, so that we may develop a better understanding of what causes the breakdown of peace in various multi-ethnic contexts and create a more comprehensive basis for peacebuilding and post-conflict development in ethnically divided societies. Literature on causes of ethnic conflict covers a number of competing theories. Some of the major explanations include: primordialist, institutional, political entrepreneurs, and competition over resources theories. But, as Jalali and Lipset argue, “Given the variety of ethnic conflicts and their dynamic and fluid qualities,

no one factor can provide a comprehensive explanation.”

In this article, I propose a conceptual framework for understanding violent ethnic conflict that combines the above mentioned approaches. The danger of attempting to develop a comprehensive approach for understanding a phenomenon that manifests in various contexts, across the globe, is simply the one of trying to do “too much.” Rather than offering a comprehensive theory of ethnic conflict, I explore some of the existing explanations and the ways and extent to which these approaches are complementary in helping us construct a broader conceptual framework for understanding the complexities of violent inter-group

I argue that ethnic conflict occurs when a particular set of factors and conditions

converge: a major structural crisis; presence of historical memories of inter-ethnic

1 James D. Fearon and David D. Laiting, “Explaining Interethnic Cooperation,” The American Political Science

Review, Vol. 90, No.4, December 1996, p. 715.

2 Ibid., p. 730.

3 Rita Jalali and Seymour Martin Lipset, “Racial and Ethnic Conflicts: A Global Perspective,” Political Science

Quarterly , Vol. 107, No. 4, 1992-93, p. 600.

4 For other attempts to develop a “global” explanation of inter-group conflict see, for example: Ted Robert Gurr,

“Why Minorities Rebel: A Global Analysis of Communal Mobilization and Conflict Since 1945,”

International

Political Science Review , Vol. 14, No. 2, April 1993. Gurr uses a statistical analysis of 227 communal groups across the world to develop a general explanation for how why these groups mobilize to defend their interests.

He finds that factors such as cultural identity, inequalities, and historical loss of autonomy contribute to group grievances, while democracy, state power, and institutional change determine the form in which the conflict manifests (e.g. protest or rebellion). Also see François Nielsen, “Toward a Theory of Ethnic Solidarity,”

American Sociological Review , Vol. 50, No. 2, April 1985. Nielsen argues that industrialization and development affect social trends in a way that facilitates mobilization along ethnic lines/ethnic solidarity. He uses a general model of ethnic collective action to examine ethnic resurgencies in modern society. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪3 grievances; institutional factors that promote ethnic intolerance; manipulation of historical memories by political entrepreneurs to evoke emotions such as fear, resentment, and hate

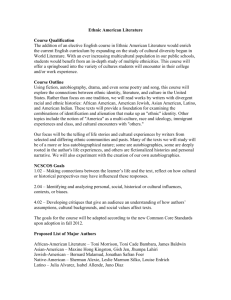

; and an inter-ethnic competition over resources and rights. Figure 1

illustrates a sequentially ordered chain of causality among these factors.

Figure 1 – Causes of Ethnic Conflict: Conceptual Framework

CONTEXT PRESENT FACTORS

MAJOR

1 1

•

Historical memories of

STRUCTURAL

CHANGE:

Uncertainty,

Instability, grievances

•

Political entrepreneurs

•

Institutional/political system factors facilitating intolerance

Fear

OUTCOME

I

COMPETITION

INTOLERANCE

VIOLENT ETHNIC

CONFLICT

Each ethnic conflict has its own unique characteristics and, in different contexts, some of these elements will be more prominent than the others, but all of them are the “common denominators” necessary for ethnic conflict to occur. The primordialist approach helps explain the role of emotions and the conflict potential of ethnicity. The institutional, political entrepreneurs and competition over resources approaches explain how the interaction of institutional and political factors with

leads to ethnification, ethnic

intolerance, competition, and eventually – violent conflict.

Ethnically diverse societies carry various degrees of conflict potential. Ethnic emotions, rooted in historical memories of grievances, are at the core of conflict potential.

Ethnicity, as Donald Horowitz argues, “embodies an element of emotional intensity that can

be readily aroused when the group’s interests are thought to be at stake.” 7

structural change (such as the collapse of communism in Bosnia and decolonization in

Rwanda and Sri Lanka) upsets previous political and institutional arrangements. When these institutional mechanisms are no longer in place, countries face a period of political and economic transition “in which the old no longer works while the new will not yet function

5 For more information on the role of emotions in ethnic conflict see: Roger D.Petersen, Understanding Ethnic

Violence: Fear, Hatred, and Resentment in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe, (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2002).

6 In this article, the term “ethnic emotions” is used to refer to emotions of animosity such as fear, hate, resentment and rage toward the “other” ethnic groups.

7 Donald L. Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict , (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985), p. 59. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪4 and the social costs grow.” 8

This creates a context of instability and uncertainty about the political, social, and economic future of the communities, or – to use Lake and Rothchild’s term – “collective fears

Such a situation facilitates a manifestation of

emotional antagonisms among ethnic groups. Political entrepreneurs, in their quest for power, mobilize ethnic constituencies by promoting inter-ethnic animosities using the rhetorical weapons of blame, fear, and hate. This results in an inter-ethnic competition over resources and rights, which is accompanied by a reconstruction of social categories of “inclusion” and

“exclusion,” ethnification and ethnic intolerance. Ethnification is defined as a situation in which “the social, psychological, and political importance of ethnic identities rise relative to

and ethnic intolerance refers to a denial of access to resources and rights to

other ethnic groups. In this article, the terms “ethnic group” and a “nation” will be used interchangeably to refer to: “a body of individuals who purportedly share cultural or racial characteristics, especially common ancestry or territorial origin, which distinguish them from

While it is recognized here that a “nation” can also refer to a

group of people who live in the same nation-state and that such a group may consist of more than one “ethnic group,” for the purposes of this article, the two terms are used to refer to the definition of a group as quoted above.

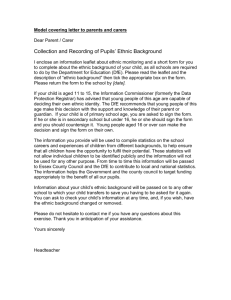

The first section of this article discusses the theoretical elements of the proposed framework for understanding ethnic conflict. The relationship between each theory and the factors that contribute to ethnic conflict is illustrated in Figure 2. In the second part of the article, the proposed conceptual framework is applied to the case of Bosnia and

8 Georg Brunner, Nationality Problems and Minority Conflicts in Eastern Europe , (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann

Foundation Publishers, 1996), p. 92.

9 David A.Lake and Donald Rothchild, “Containing Fear: The Origins and Management of Ethnic Conflict,”

International Security , Vol. 21, No. 2, Fall 1996, p. 41.

10 Murat Somer, “Explaining the Hardly Predictable: Causes and Consequences of Ethnification,” Working

Paper, Center for International Studies, USC, November 12, 1997.

11 Chaim Kaufmann, “Possible and Impossible Solutions to Ethnic Civil Wars,” International Security , Vol. 20,

No. 4, Spring 1996, p. 138.

12 The framework has also been applied to ethnic conflicts in Rwanda and Sri Lanka. See Bojana Blagojevic,

“Ethnic Conflict and Post-Conflict Development: Peacebuilding in Ethnically Divided Societies,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, 2004). http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict

Figure 2: Causes of Ethnic Conflict: Theoretical Elements

Context:

MAJOR STRUCTURAL

CHANGE

Theory

Primordalist

Explains

Explain

< r v

ETHNIC EMOTIONS,

CONFLICT POTENTIAL

Socially constructed sense of

“primordial” group history and animosity based on historical memories of grievances/injustice t

Interaction of institutional and political factors with ethnic emotions leads to

ETHNIFICATION

ETHNIC INTOLERANCE,

COMPETITION

1

VIOLENT ETHNIC

CONFLICT

▪5

Primordialist Approach

The primordialist approach asserts the existence of “ancient hatreds” among ethnic and cultural groups: “the urge to define and reject the other goes back to our remotest human ancestors, and indeed beyond them to our animal predecessors.” 13

According to this view,

“tendencies toward xenophobia and intolerance are more natural to human societies than

liberal politics of interest.” 14

The primordialist approach helps explain the role of emotions in

13 Quoted in Bernard Lewis, “Muslims, Christians and Jews: The Dream of Coexistence,” New York Review of

Books , 26 March 1992, p. 48.

14 Beverly Crawford, “The Causes of Cultural Conflict: An Institutional Approach” in Beverly Crawford and

Ronnie D. Lipschutz, eds., The Myth of “Ethnic Conflict” , International and Area Studies Research

Series/Number 98, (Berkeley: University of California, 1998), p.11. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪6 ethnic conflict and the conflict potential of ethnicity. While ethnic emotions appear to be primordial , they are a socially and politically constructed reality – drawn from the historical memories of past injustices and grievances. Suny illustrates this by stating that,

National identities are saturated with emotions that have been created through teaching, repetition, and daily reproduction until they become common sense.(…)

These tropes – betrayal, treachery, threats from others, and survival – are embedded in familiar emotions – anxiety, fear, insecurity, and pride.

15

Group history is socially constructed. As Suny argues, “Nations are particular forms of

collectivity that are constituted by a process of creating histories.” 16

further explains, is constructed so that it consists of “continuity, antiquity of origins, heroism

and past greatness, martyrdom and sacrifice, victimization and overcoming of trauma.” 17

Also, “the past(…)gives this particular form of imagined community a potent claim to

territory, the ‘homeland.’” 18

We cannot prove that ethnic animosities are primordial, but we can establish their historical roots in collective memory. Prazauskas defines a historical memory of an ethnic group as a “set of ideas about the past history of the group, its historical relations with other

groups, ethnic images and self-images.”

Ethnic communities use historical memories of

past grievances as a point of reference – a source of ethnic animosities and a justification for discriminatory actions against other ethnic groups. As Ahmed Akbar notes,

History is employed to buttress ethnic and religious polemics and, more importantly, to reclaim and re-construct ethnic identity(…)Honour, identity and the media, the past and the future, the rise of what is called fundamentalism or revivalism all relate to the

Similarly, Rothschild argues that, under the contemporary conditions of rapid change,

“people often cleave to, or rediscover, or even invent, their ethnicity – putatively rooted in

15 Ronald Grigor Suny, “Why We Hate You: The Passions of Religious and Ethnic Violence,” A Talk for

Purdue University, November 7, 2002.

16 Ronald Grigor Suny, “Constructing Primordialism: Old Histories for New Nations,” The Journal of Modern

History, Vol. 73, No. 4, December 2001, p. 869.

17 Ibid., p. 870.

18 Ibid.

19 Algis Prazauskas, “Ethnic Identity, Historical Memory, and Nationalism in Post-Soviet States”, Working Paper,

March 1995 in Columbia International Affairs Online , paragraph 12, http://www.ciaonet.org

, (accessed 5 July

2004).

20 Ahmed S. Akbar, “’Ethnic Cleansing’: A Metaphor of Our Time?,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1,

1995, p. 20. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪7

‘primordial’ bonds – for personal identification, emotional security, and communal anchorage.” 21

In its “pure” form, the primordialist view implies a sense of hopelessness. If “one is invariably and always a Serb, a Zulu, or Chechen” and if “ethnic divisions and tensions are

then little or nothing can be done to prevent or resolve ethnic conflict.

Understanding ethnic hatred as something that is ingrained in ethnic groups and cannot be changed is a simplified view of a complex problem. It prevents those who build peace to see that ethnic animosities exist in combination with other factors and that addressing each dimension of the problem is necessary to resolve conflict. Confining explanations of ethnic conflict solely to primordial causes also implies a degree of ignorance and prejudice towards the societies affected by conflict. As Akbar describes, “Ideas and arguments about ethnicity are usually based on the assumption that ethnic identity is a characteristic of primordial and tribal societies…Only backward

societies cling to the past.” 23

All multi-ethnic societies, when subject to a convergence of a particular set of factors and conditions, carry the potential of ethnic conflict. Under the stress of a major structural change that brings a sense of chaos and uncertainty, the consciousness of historically rooted ethnic identities and emotions are employed as vehicles to ethnic violence for political purposes. Viewing historically rooted ethnic animosities as the only cause of conflict is insufficient. As Ganguly argues, “A proper understanding of the causes of ethnic political mobilization and conflict is crucial, and we must move beyond simplistic discussions of

‘ancient hatreds’ to search for more systematic explanations.” 24

historical and current realities as a result of pre-determined or “primordial” factors, then,

“The road is open to exclusivist, homogeneous nations that in our ethnically mixed, fluid,

changing world re-quire desperate policies of deportation and ethnic cleansing to secure.”

On the other hand, as Suny argues, if we view our realities as socially constructed, the

possibilities for cooperation and peaceful cohabitation are greater.

21 Joseph Rothschild, Ethnopolitics: A Conceptual Framework, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), p. 247.

22 David A. Lake and Donald Rothchild, “Ethnic Fears and Global Engagement: The International Spread and

Management of Ethnic Conflict,” Working Paper, Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, January 1996.

23 Ahmed S. Akbar, “’Ethnic Cleansing’: A Metaphor of Our Time?,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1,

1995, p. 6, emphasis added.

24 Rajat Ganguly, “Why Do Ethnic Groups Mobilize?” (Chapter 3) in R. Taras, ed., National Identities and

Ethnic Minorities in Eastern Europe , Selected papers from the Fifth World Congress of Central and East

European Studies, Warshaw, 1995, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, Inc., 1998), p. 49.

25 Ronald Grigor Suny, “Constructing Primordialism: Old Histories for New Nations,” The Journal of Modern

History, Vol. 73, No. 4, December 2001, p. 896.

26 Ibid. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic

▪8

Institutional Approach

Institutions play an important role in regulating the level of the conflict potential of ethnicity. They define inter-ethnic relationships by either facilitating or obstructing inter-group cooperation. Crawford notes that institutions “both constrain behavior and provide incentives for cooperation and compliance in norms, rules, and procedures for allocation, participation, representation, and accountability.

According to her, whether or not identity politics turns into violent conflict depends on the functioning of state institutions: “Where identity politics is practiced, states can channel it in peaceful political competition as long as they can make credible commitments to shape and uphold agreements

made among culturally defined political actors. The proponents of the institutional approach would

argue, for example, that the nineteenth century tensions among the three ethnic groups in Switzerland are now managed by the current political system (consociational democracy) by institutionalizing

ethnic pluralism and giving the three groups equivalent power-sharing. On the other hand, as Enloe

and Nagel argue, if the state’s administrative structures and legal institutions distribute resources

political institutions politicize cultural [ethnic] identity are more vulnerable to cultural [ethnic] conflict than countries whose political institutions promote social integration of diverse cultural groups.

Communist, colonial and democratic political arrangements have various institutional effects on inter-ethnic relations and thus on conflict potential. For example, communism is sometimes blamed for creating or reinforcing ethnic/national divisions but suppressing the expression of ethnic conflicts, and consequently, for recent outbursts of ethnic violence in the post-communist regions of the world following the system collapse. In the words of Georg Brunner, in the communist systems,

“nationality [ethnicity] conflicts were suppressed, compulsorily canalized or even consciously

instrumentalized. Colonial political systems used the “divide and rule” strategy to create and/or

separate groups along ethnic lines in order to strengthen the power of the colonial system. Once decolonization took place, the absence of old institutional mechanisms of group control allowed for ethnic emotions to surface and

27 Beverly Crawford, “The Causes of Cultural Conflict: An Institutional Approach” in Beverly Crawford and

Ronnie D. Lipschutz, eds.,

The Myth of “Ethnic Conflict”,

International and Area Studies Research

Series/Number 98, (Berkeley: University of California, 1998), p. 17.

28 Beverly Crawford, “The Causes of Cultural Conflict: Assessing the Evidence” in Ibid., p. 517.

29 Ibid., p. 597-8.

30 Cynthia Enloe, “The Growth of the State and Ethnic Mobilization: The American Experience,” Ethnic and

Racial Studies, 4, April 1981, pp. 123-36; Joane Nagel, “The Political Construction of Ethnicity” in Olzak and

Nagel, eds., Competitive Ethnic Relations , (Boston: Academic Press, 1986), pp. 93-112.

31 Beverly Crawford, “The Causes of Cultural Conflict: Assessing the Evidence” in Beverly Crawford and

Ronnie D. Lipschutz, eds., The Myth of Ethnic Conflict, International and Area Studies Research Series/Number

98, (Berkeley: University of California, 1998), p. 556.

32 Georg Brunner, Nationality Problems and Minority Conflicts in Eastern Europe , (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann

Foundation Publishers, 1996), p. 92.

http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪9 ethnic intolerance to take place. Such a situation, exploited by political entrepreneurs, leads to inter-ethnic competition and conflict.

Democratic institutions are considered to promote inter-ethnic cooperation and thus mitigate the conflict potential of ethnicity. According to Prazauskas, “In a democratic multinational state, stability is generally maintained by means of political bargaining and compromise between ethnic subgroups.” 33

Dixon similarly argues that “democratic states…are better equipped than others with the means for diffusing conflict situations at and

early stage before they have an opportunity to escalate to military violence.” 34

while conflict may not happen in or among established democracies, conflict often does happen in democratizing states. In Prazauskas’ words,

The transition from authoritarianism to democracy in multinational states means first of all the disintegration of the coercive system of checks and controls. This inevitably leads to ethnic flare-ups as ethnic communities begin to organize, to mobilize their

members, and to voice their grievances and demands upon the state and each other.

Furthermore, introduction of the majority democracy rule in ethnically divided societies in the context of a major structural change promotes fear of domination and marginalization by other groups. As Lijphart argues, “Majority rule spells majority dictatorship and civil strife rather than democracy…What such societies need is a democratic regime that emphasizes

consensus instead of opposition that includes rather than excludes.” 36

Political Entrepreneurs Approach

The instability and uncertainty that result from a major structural change and the institutional inability to regulate inter-ethnic relations provides a “perfect” condition in which political entrepreneurs can manipulate ethnic emotions in order to mobilize groups for their own political purposes. Politicians exploit ethnic differences by drawing upon historical memories of grievances and “whip up” hatred in order to gain or strengthen their power. The dynamic that develops between political entrepreneurs and their followers causes an inter-ethnic security dilemma. As Stuart Kaufman explains, “belligerent leaders stoke mass hostility; hostile masses support belligerent leaders, and both together threaten other groups, creating a

33 Algis Prazauskas, “Ethnic Conflicts in the Context of Democratizing Political Systems,” Theory and Society , vol. 20, 1991, pp. 581-2.

34 William J. Dixon, “Democracy and the Peaceful Settlement of International Conflict,” American Political

Science Review , Vol. 88, No. 1, March 1994, p. 14.

35 Algis Prazauskas, “Ethnic Conflicts in the Context of Democratizing Political Systems,” Theory and Society , vol. 20, 1991, p. 596.

36 Arend Lijphart, Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries , (New

Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), p. 33. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪10 security dilemma which in turn encourages even more mass hostility and leadership belligerence.” 37

Political entrepreneurs manipulate fears and uncertainties of ethnic groups they represent and are able to “awaken a consciousness of common grievances and a desire to

rectify these wrongs.” 38 They help create and reinforce ethnic polarization in the society.

Furthermore, “Ethnic cleavages allow political entrepreneurs to mobilize grievances against

distributions of benefits that are perceived to be unfavorable to the group.”

blame, and hate are used by political entrepreneurs as a tool of division and control.

According to Zupanov and his co-authors, “Politicians whose goal is that of exploiting and/or provoking ethnic/national hatred are in control of media production which is controlled and directed by hate-prone politicians that provokes national intolerance and hatred in the

population leading to violence.” 40

Therefore, the politicians’ manipulation of ethnic emotions

leads to particular actions – such as intolerance. As Brunner argues,

The disposition towards national [ethnic] intolerance can be strengthened by new [or old] political leadership if the leaders do not have the necessary political sense of responsibility and do not resist the temptation to avert attention from the acute socioeconomic problems by creating national concepts of enemies. This is the big chance

for the forces of the old regimes who either lost, or are afraid of losing, their power.

The political entrepreneurs approach to explaining the causes of ethnic conflict is closely related to the institutional approach. Politicians who use ethnicity to their advantage can successfully operate only within those institutional arrangements that support/allow such practice or are unable to prevent it. The success of political entrepreneurs in mobilizing ethnic groups into violent conflict depends on the strength of the existing state institutions: “If states provide a legitimate arena for entrepreneurs to compete and if resources available for allocation are abundant, identity politics, like other kinds of political competition, will be

legitimate and stable.” 42 However, if state institutions fail, “previous incentives promoting

social and political divisions along cultural [ethnic] lines are likely to persist and ethnic and sectarian political entrepreneurs may have a stash of resources to distribute in exchange for

37 Stuart J. Kaufman, “Spiraling to Ethnic War: Elite, Masses, and Moscow in Moldova’s Civil War,”

International Security, Vol. 21, No. 2, Fall 1996, p. 109.

38 David A. Lake and Donald Rothchild, “Ethnic Fears and Global Engagement: The International Spread and

Management of Ethnic Conflict,” Working Paper, Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, January 1996.

39 Ibid.

40 Josip Zupanov, et. Al, “A Breakdown of the Civil Order: The Balkan Bloodbath,” International Journal of

Politics, Culture and Society , Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996, pp. 413-14.

41 Georg Brunner, Nationality Problems and Minority Conflicts in Eastern Europe , (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann

Foundation Publishers, 1996), p. 92.

42 Beverly Crawford, “The Causes of Cultural Conflict: Assessing the Evidence” in Beverly Crawford and Ronnie

D. Lipschutz, eds., The Myth of Ethnic Conflict, International and Area Studies Research Series/Number 98,

(Berkeley: University of California, 1998), p. 556. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict

▪11 support. Morris similarly illustrates the connection between political leadership and institutions. According to her, the two are “the filter through which all other causes of conflict

have to pass. She also notes that institutions can fuel grievances through political

ff

exclusion or ineiciency.

Competition over Resources Approach

Political mobilization of ethnic identities results in ethnic intolerance and competition over resources and rights - which, if unresolved, can lead to a violent conflict. When resources are scarce, it is easier for political entrepreneurs to capitalize on the conflict potential of ethnicity.

As described by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and

United States Agency for International Development (USAID), “These groups are all the more likely to be vulnerable to such maneuvering when they find themselves in situations

characterized by a lack of opportunities. When scholars discuss competition over resources,

they often refer to the economic competition over resources. The argument is that: under difficult economic conditions, high unemployment and poor prospects for the future, people feel victimized and blame their misfortune on other ethnic group(s). This leads to inter-ethnic competition. In this article, I expand the concept of resources to include not only economic, but also political, social, and cultural “goods” that not only include material security but also encompass individual and group rights. As Lake and Rothchild note,

Property rights, jobs, scholarships, educational admissions, language rights, government contracts, and development allocations all confer particular benefits on individuals and groups. Whether finite in supply or not, all such resources are scarce and, thus, objects of competition and occasionally struggle between individuals and,

when organized, groups.

In his analysis of peace accords and ethnic conflicts, de Varennes (2003) found that in almost all conflicts, ethnic groups’ demands focused on securing basic rights for their group. For example, they demanded more effective political participation, a fairer share and distribution of education, employment opportunities, etc. As Williams explains,

The likelihood of conflict is higher when disagreement and opposition concern collective goods, e.g. language rights, religious beliefs and symbols, civil and political

43 Ibid.

44 Sharon Morris, “Assessing Conflict Vulnerability,” Democracy Dialogue, Technical Notes From USAID

Office of Democracy and Governance, December 2001, p. 3.

45 Ibid.

46 OECD-USAID,“Land, Conflict and Development: What Role of Donors?,” Summary, OECD-USAID

Informal Experts’ Seminar, 19 and 20 June 2003, p. 2

47 David A. Lake and Donald Rothchild, “Ethnic Fears and Global Engagement: The International Spread and

Management of Ethnic Conflict,” Working Paper, Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, January 1996. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪12 rights and privileges, regional-ethnic power, or regional-ethnic parity in the economy.

The more nearly indivisible the goods and the less the access of the ‘disadvantaged,’ the greater is the resentment and the more likely is ethnic mobilization, followed by overt conflict.

48

In the literature, there are various notions on what mechanisms may facilitate ethnic competition. These mechanisms include economic and political processes such as: racially

the cultural division of labor,

concept of “internal colonialism” has been used extensively to account for economic and

political differences along ethnic lines.

According to the internal colony theory, when a

group establishes its dominance within the society, it is able to maintain “a cultural division of labor: a system of stratification where objective cultural distinctions are superimposed

In the context of a major structural change within an ethnically diverse

society, political entrepreneurs attribute their ethnic group’s have-nots to the exploitation and denial of access to resources and rights by the other “groups.” Advantaged groups, on the other hand, begin to see the “others” as those who will take away their “haves” should they gain a position of power within the society. Institutional factors fuel inter-ethnic competition by facilitating politics of exclusion.

When ethnic groups find themselves victimized and/or threatened by other groups, identification in terms of their ethnicity becomes particularly important, because their ethnic group is seen as the source of protection from other groups and a possible provider of a secure environment. Inter-ethnic competition can lead to “the silencing of divergent opinions,

48 R. M. Williams, “The Sociology of Ethnic Conflicts: Comparative International Perspectives,” Annual Review of Sociology, No. 20, 1994, p. 55.

49 Edna Bonacich, “A Theory of Ethnic Antagonism: The Split Labor Market,” American Sociological Review , vol. 38, 1972, pp. 547-59.

50 Edna Bonacich and J. Modell, The Economic Basis of Ethnic Solidarity: Small Business in the Japanese

American Community, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980).

51 Michael Hechter, “Group Formation and the Cultural Division of Labor,” American Journal of Sociology , vol.

84, no. 2, 1978, pp. 293-318.

52 Michael T. Hannan, “The Dynamics of Ethnic Boundaries in Modern States,” in J. W. Meyer and Michael T.

Hannan (eds), National Development and the World System , (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), pp.

253-75.

53 Olzak, Susan and Joane Nagel, eds., Competitive Ethnic Relations , (Orlando and Boston Academic Press,

1986), pp. 93-112.

54 A. J. Kposowa and J.C. Jenkins, “The Structural Sources of Military Coups in Postcolonial Africa, 1957-

1984,” American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 99, No. 1, 1993, pp. 126-63.

55 M. J. Yinger, “Ethnicity,” Annual Review of Sociology , Vol. 11, 1985, p. 165.

56 Michael Hechter, Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, 1936-1966,

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), p. 30. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪13 increases in adherence to group symbols, and intolerance for out-groups and dissenters.” 57 In the absence of an intervention, violent ethnic conflict is the final outcome.

Case Study: Bosnia and Herzegovina

Introduction

In this section of the article, I will apply the above discussed framework for understanding ethnic conflict to the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnia is a post-communist country, formerly one of the six constituent republics of former Yugoslavia. According to a 1991 census, 17.3 per cent of Bosnian population identified as Croats, 43.7 per cent as Muslims,

31.4 per cent as Serbs, and 7.6 per cent as Yugoslav and others.

ethnic war in Bosnia, the country was considered a symbol of interethnic cooperation, as the groups were able to “get along” and coexist peacefully. The relations among the three ethnic groups in Bosnia had begun to deteriorate due to both a revival of the historical memories of grievances (particularly from the period of World War II) and due to a context of economic, political, and social uncertainty. As the Cold War came to an end and communism collapsed,

Bosnia had begun its uncertain transition from a communist regime to a democracy and free market economy. The first multi-party elections since the World War II were held in

November and December 1990. The election resulted in the victory of three leading nationalist parties, ending the monopoly of the communist party. The war among the three ethnic groups in Bosnia broke out shortly after the country declared its independence in

March of 1992. About 250,000 people were killed in the Bosnian war, and a half of the

country’s surviving population (about 2 million) was displaced internally and abroad.

The collapse of communism in former Yugoslavia and the ensuing process of democratization represent the major structural change that influenced the context for development of ethnic conflict in Bosnia. Political institutions lost their ability to regulate inter-ethnic relations and keep the expression of ethnic emotions in check. Political entrepreneurs manipulated the conflict potential of ethnicity for their own political gain.

Local, national and international political actors stood by as inter-ethnic intolerance and competition over resources and rights intensified and escalated into a violent ethnic conflict.

57 Susan Olzak and Elizabeth West, “Ethnic Conflict and the Rise and Fall of Ethnic Newspapers,” American

Sociological Review , Vol. 56, 1991, pp. 458-74.

58 The Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Profile: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia , (London: The

Economist Intelligence Unit, 1995-96), p.3.

59 Adrian Karantnycky, et al., eds., Nations in Transit 1998: Civil Society, Democracy, and Markets in East

Central Europe and the Newly Independent States, (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, Freedom House,

Inc., 1999), p.128 http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪14

Hatred from the Past

A common explanation of ethnic conflicts in former Yugoslavia is that the “ancient hatreds” among the three ethnic groups are to blame for the violence. As Zupanov and his co-authors note, “The crude version of this theory explains the ongoing wars in the former Yugoslavia as a normal way of resolving conflicts among the ‘wild’ Balkan tribes.” 60

Many prominent international actors also expressed their belief in the primordial explanation of ethnic conflict in Bosnia/former Yugoslavia. In a statement made on March 28, 1993, the Secretary of State,

Warren Christopher, said, “The hatred between all three groups, the Bosnians and the Serbs

and the Croats, is almost unbelievable. It’s almost terrifying, and it’s centuries old.” 61

Similarly, the British Foreign Secretary, Douglass Hurd, told the Associated Press on July 20,

1992 that, “One of the things one learns from actually being here is that the fears and hatreds

which have been unleashed are absolutely formidable.” 62

In her “Letter from Washington,”

Elizabeth Drew stated that, “the disappearance of the Iron Curtain allowed long-suppressed –

but no less bitter – ethnic hatreds to break out once more.”

Another analyst of the conflicts

in former Yugoslavia directly labeled the people of the region as emotion-driven, irrational human beings, implicitly inferior to the “civilized” West:

It is all too easy for Western Europeans or Americans to fall into the trap of expecting superficially similar, European, South Slavs to think and react in similar fashion to themselves. The Slavic [sic] nationalities of former Yugoslavia are tribal societies, governed more by their emotions than by their intellects. Moreover, these emotions

are primitive, atavistic, and not those shaped by late twentieth century liberal values.

While it is true that ethnic emotions in Bosnia were rooted in historical memories of grievances, the hatred did not exist consistently over “centuries.” Memories of past injustices committed by the “others” were revived by opportunist politicians to evoke emotions of fear, resentment, rage, and hate. Institutional arrangements facilitated their divisive efforts. As

Snyder notes, “Contrary to what some would have us believe, Serbs and Croats fought each other very little before this century….Contemporary ethnic violence stems as much from

deliberate government policies as from traditional communal antagonisms.” 65

between Serbs and Croats did not exist before 1918, when the Yugoslav state was created, and before the massacres of World War II, there were no major, violent conflicts between the

60 Josip Zupanov, et al., “A Breakdown of the Civil Order: The Balkan Bloodbath,” International Journal of

Politics, Culture and Society , Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996, p. 405

61 Quoted in Ibid.

62 Randy Hodson, et al., “National Tolerance in the Former Yugoslavia,” The American Journal of Sociology ,

Vol. 99, No. 6, May 1994, p. 1535.

63 Elizabeth Drew, “Letter from Washington,” New Yorker , No. 68, July 2, 1992, p. 70.

64 C. J. Dick, “Serbian Responses to Intervention in Bosnia-Hercegovina,” British Army Review , No. 102, Dec.

1992, pp. 18-25.

65 Jack Snyder, “Nationalism and the Crisis of the Post-Soviet State,” Survival , Vol. 35, No. 1, Spring 1993, pp.

5-26. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪15 two groups.

66

During the World War II, Croatia was a Nazi protectorate and was given the possession of virtually entire Bosnia and Herzegovina. Some Muslims collaborated with

Croatia’s Ustasha fascist regime, although majority did not. Hundreds of thousands of Serbs were murdered by the “Ustasha,” while the Serbian nationalist “Chetnik” forces massacred

These massacres are an example of a historical memory – a

source of grievance, hate, resentment, and fear. At the same time, the three ethnic groups fought together against Nazis in the communist, Partizani forces. In the past, there are examples of both – ethnic groups working together and turning against each other. In the case of the ethnic conflict in Bosnia, the primordial explanation points to ethnic emotions stemming from historical memories of grievances. However, as Hodson and his co-authors note, “Arguments based on primordial hatreds should not be accepted without an examination

of the possible structural underpinnings of current animosities.”

The presence of deep, historically rooted ethnic animosities alone is not sufficient to create conflict, as other factors must be involved as well for ethnic conflict to result.

Institutional (political system) theory helps explain how, following the collapse of communism, the political institutions in Bosnia were no longer able to regulate inter-ethnic relations and control ethnic animosities, thus facilitating political entrepreneurs’ efforts to manipulate the groups to serve their own interests.

The Collapse of Communism and Transition to Democracy

While different groups in former Yugoslavia were allowed to express some basic inter-group distinctions during the communist rule, “any expression of nationalism, particularly religiously-based, was ruthlessly suppressed: throwing national hatreds into what Misha

Glenny calls ‘history’s deep freeze.’” 69

When the communist system collapsed, the once

“frozen” “hatreds,” were violently unleashed. As Szayna argues, “The tensions came out into the open in central Europe and the Balkans because of the breakdown of the ruling system in

the region and the massive, regionwide regime change.” 70

“Communist rule not only froze or disfigured many of the unresolved nationality questions, but it also created additional grievances and new sources of friction in various parts of the

66 Josip Zupanov et al., “A Breakdown of the Civil Order: The Balkan Bloodbath,” International Journal of

Politics, Culture and Society , Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996, p. 406.

67 Janusz Bugajski, Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and

Parties , The Center for Strategic and International Studies, (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1994), p. 6.

68 Randy Hodson, et. al., “National Tolerance in the Former Yugoslavia,” The American Journal of Sociology ,

Vol. 99, No. 6, May 1994, p. 1535.

69 Paul Roe, Ethnic Violence and the Societal Security Dilemma, (New York: Routledge, 2005), p. 86.

70 Thomas S. Szayna. Ethnic Conflict in Central Europe and the Balkans: A Framework for U.S. Policy

Options , (Santa Monica: Rand, 1994), p. 8. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪16 region.” 71

One of the ways in which the Communist regime attempted to discourage manifestations of ethnic nationalisms was by promoting people’s allegiance to an overarching identity of socialist Yugoslavism . However, as Roe notes, these efforts may have distracted

from but not eliminated group nationalisms (e.g. “Serbism” and “Croatism”).

federation was constructed along national/ethnic lines. While most groups could identify with one of the federal republics as their “homeland” (for example, Croats with Croatia, Serbs with

Serbia, etc.), Muslims, although they received the status of a “nation” (national group) in

1963, 73 had an “ambiguous” relationship with the territory of the republic of Bosnia.

quest of Muslims in Bosnia for Bosnian independence in the post-communist, early 1990s can be linked to the unresolved issues of their status as a group during Communism. Even before the collapse of communism there were “efforts by some Muslim intellectuals to revive the notion of ‘Bosnianism’ in place of ‘Muslimness’ as a basis for defining the Muslim’s claim to power in the republic.” 75

After the collapse of communism, Bosnia and the rest of the former republics of

Yugoslavia found themselves in the process of democratization. For the believers in democracy and democratic peace, the assumption is that a democratic political system would lead to peace among and within nations. In his State of the Union Address in 1994, President

Bill Clinton argued that democratization would be an antidote to war and civil strife.

However, as Snyder points out, “While the world would undoubtedly be more peaceful if all states became mature democracies, Clinton’s conventional wisdom failed to anticipate the

dangers of getting from here to there.” 77

As Luc Reychler puts it, “the devil is in the transition.” 78

According to Snyder, the transition to democracy seems to have facilitated the

ethnic conflict. He argues that, “a country’s first steps toward democracy spur the development of nationalism and heighten the risk of international war and internal ethnic

Misha Glenny argues that, “No East European country has demonstrated quite so

clearly as the former Yugoslavia the dangers which were inherent but largely unrecognized in

the process of democratization.” 80 In ethnically polarized societies, where ethno-nationalism

71 Janusz Bugajski, Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and

Parties , The Center for Strategic and International Studies, (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1994), p. xi.

72 Paul Roe, Ethnic Violence and the Societal Security Dilemma, (New York: Routledge, 2005), p. 86.

73 Steven L. Burg and Paul S. Shoup, The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International

Intervention, (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1999), p. 41.

74 Ibid., p. 43.

75 Ibid., p. 44.

76 Bill Clinton, State of the Union Address 1994, “Transcript of Clinton’s Address,” New York Times , January

26, 1994, p. A17.

77 Jack Snyder, From Voting to Violence: Democratization and Nationalist Conflict, (New York: W.W. Norton

& Company, Inc., 2000), p. 15.

78 Luc Reychler, Democratic Peace-Building and Conflict Prevention: The Devil is in Transition, ( Leuven:

Leuven University Press, Center for Peace Research and Strategic Studies (CPRS), 1999).

79 Jack Snyder, From Voting to Violence: Democratization and Nationalist Conflict, (New York: W.W. Norton

& Company, Inc., 2000), p. 352.

80 Misha Glenny, The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War, (London: Penguin Books, 1992), p. 235. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪17 and ethnification processes are present, instituting a majoritarian democracy results in further polarization and competition to secure ethnic group rights and access to resources. In fear of or reaction to being targets of ethnic intolerance, ethnic groups intensify the process of ethnification in order to prevent the other group(s) from gaining majority power in the society through democratic processes. As Vejvoda notes, “Majoritarian democracy has proved fatal in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina.” 81

Before the war broke out, the Bosnian political system consisted of a three-way power-sharing relationship – a “‘communist consociationalism’ of sorts, with no group

having a majority.” 82 After the collapse of communism, Bosnia’s first political step was to

build a democratic, majority-rule political model. A consociational democratic model,

Vejvoda argues, would have been a better political solution.

In the first multi-party elections

held in Bosnia in October and November 1990, three “nationalist” parties, each representing one ethnic group, won the elections. Their coming into power set off a competitive process of political, ethnic entrepreneurship, disguised by each party’s claims to represent their group’s best interest in shaping the future of Bosnia. The Bosnian Serb leaders strove to keep Bosnia as a part of the remainder of the former Yugoslavia (and thus connected to Serbia), while

Bosnian Muslims and Croats supported Bosnia’s separation from Yugoslavia. In a referendum held in March 1992, 63.4 per cent of eligible voters cast their vote regarding

Bosnia’s independence. Serbian leaders encouraged Bosnian Serbs to boycott the referendum and declared the process illegal. Of those who participated, 99.7 per cent of respondents supported a sovereign and independent Bosnia and Herzegovina. In April 1992, Bosnia was recognized internationally as an independent state. The armed conflict was launched by the

Bosnian Serb leaders in May 1992.

No ethnic group trusted the motives of the other or

wanted to risk having the access to resources and rights controlled by another group. It was the political entrepreneurs who assured each ethnic group that a scenario in which they did not hold power would prove disastrous. As Glenny argues,

Bosnia could only have been saved if a political party which spanned the three communities had emerged as the most powerful after the collapse of communist power. The poverty of the pluralist system based on the three national parties was demonstrated by the structures which it spawned. In its eighteen-month-long existence, the Bosnian parliament failed to pass a single law – instead it issued a

81 Ivan Vejvoda, “By Way of Conclusion: To Avoid the Extremes of Suffering” (Chapter 14) in David A. Dyker and Ivan Vejvoda, eds., Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth , (London:

Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), p. 255.

82 Ibid., p. 253.

83 Ibid., p. 255.

84 Janusz Bugajski, Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and

Parties , The Center for Strategic and International Studies, (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1994), pp 33-5. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪18 string of declarations and memoranda which were invariably contested by one of the three national groups.

85

Manipulation by Nationalist Leaders

As the former Yugoslavia suffered a major structural change and found itself on a dangerous political crossroads, nationalist intellectuals and leaders used the weapons of nationalist rhetoric to intensify ethnic divisions and ethnic intolerance. According to Vejvoda, a consensus started to emerge among the nationalist leaders in Bosnia to seize the “opportunity presented by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of communism to ‘sort out’ interethnic grievances. Those who opposed the processes of ethnic homogenization and possible

escalation of conflict were marginalized.” 86

Thus, the economic, political and social crisis

caused a readily “mobilizable” emotional response. Nationalist leaders used the rhetoric of

“us” (our ethnic/national group) being exploited by “them” (other ethnic/national groups).

“Everybody had a grudge against Yugoslavia and against each other.” 87 The manipulation of

emotions culminated in ethnic violence which, as Bringa argues, “was the expression of a

politically organized attempt to radically redefining categories of belonging.” 88

was afraid about the uncertain fate of Bosnia, especially after the news of a meeting between

Presidents Tudjman (of Croatia) and Milosevic (of Serbia) in March 1991, reportedly

focusing on their plans for the partition of the country.

Political entrepreneurs used the primordialist argument to justify their own aims. For example, Radovan Karadzic, a Bosnian Serb leader during the war, said to the American

Ambassador to Yugoslavia, “You have to understand Serbs, Mr. Zimmerman. They have been betrayed for centuries. Today they cannot live with other nations. They must have their

own separate existence.” 90 As Zimmermann notes, political entrepreneurs, particularly the use

of the media by politicians to incite ethnic hatred in former Yugoslavia played an important role in causing the conflict:

The breakup of Yugoslavia is a classic example of nationalism from the top-down and manipulated nationalism in a region where peace has historically prevailed more than

85 M. Glenny, The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War , (London: Penguin Books, 1992), p. 148.

86 Ivan Vejvoda, “By Way of Conclusion: To Avoid the Extremes of Suffering” (Chapter 14) in David A. Dyker and Ivan Vejvoda, eds., Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth , (London:

Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), p. 255.

87 Ibid.

88 Tone Bringa, “Averted Gaze: Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1992-1995,” in Alexander Laban Hinton, ed.,

Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide , (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), p.

194.

89 Ivan Vejvoda, “By Way of Conclusion: To Avoid the Extremes of Suffering” (Chapter 14) in David A. Dyker and Ivan Vejvoda, eds., Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth , (London:

Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), p. 254.

90 Quoted in W. Zimmermann, W., “Memoirs of the Last American Ambassador to Yugoslavia,” Foreign

Affairs , Vol. 74, No. 2, 1995, p. 20. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪19 war and in which a quarter of the population were in mixed marriages. The manipulators condoned and even provoked local ethnic violence in order to engender animosities that could then be magnified by the press, leading to further violence.

91

In their mobilization of ethnicity, the political entrepreneurs were also exclusionary toward members of their own group who did not follow the extremist, ethno-nationalist approach.

Moderate politicians who did not demonize the other or did not fully identify with their own group’s politics also became targets of exclusion. For example, in 1992, the leader of the

Croatian Democratic Union in Bosnia was dismissed on the grounds that he was “too much

Bosnian, too little Croat.” 92

Political entrepreneurs’ manipulation of ethnic emotions was facilitated by the overall conditions created by the processes of change after the collapse of communism. As

Woodward notes, the argument that the war in Bosnia (former Yugoslavia) was solely the plan of Slobodan Milosevic “ignores the conditions that make such leaders possible and

popular and therefore also ignores the policies necessary to end their rule.” 93

consider the institutional factors as well. According to Zupanov and his co-authors,

It was a prevailing authoritarian political culture in all regions of former Yugoslavia that enabled nationalist leaders to monopolize the media and to increase the level of intolerance regardless of previously existing tolerance. An already existing authoritarian political culture in interaction with the monopolization of media by nationalist political leaders combined to cancel out previously high levels of tolerance

and to produce violence among populations where it had not previously existed.

Competition over Economic and Political Resources

The competition over resources argument provides the final “piece” of explanation for the violent ethnic conflict in Bosnia. The fall of communism and the transition to democracy and a free economy was marked by an economic crisis and a rising rate of unemployment. As

Woodward (1997) describes, the decline in quality of life (i.e. availability of resources) had begun prior to the actual collapse of communism and the situation was worsened when the system collapsed. According to her, up to 80 per cent of the population was experiencing a steady decline in living standards since 1970s:

91 Ibid.

92 Quoted in Chaim Kaufman, “Possible and Impossible Solutions to Ethnic Wars,” International Security , Vol.

21, No. 2, Fall 1996, p. 143.

93 Susan L. Woodward, Balkan Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution after the Cold War , (Washington DC: The

Brookings Institution, 1995), p. 15.

94 Josip Zupanov, et. al, “A Breakdown of the Civil Order: The Balkan Bloodbath,” International Journal of

Politics, Culture and Society , Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996, p. 421. http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪20

(…) this growing sense of material insecurity, that there was no sign of relief, occurred in the context of international change and domestic economic and political reform that also pulled the rug out from under the mechanisms by which social peace had been guaranteed in the country since World War II.

95

According to Woodward, the new situation resulted in “a breakdown in routine expectations

about the future” and “growing uncertainty and opportunity.” 96

transition period to ensure that all ethnic groups work together to overcome the crisis and find a solution based on the principles of equality and non-discrimination did exist. Unfortunately, the first to seize the opportunity of uncertainty were the political entrepreneurs who used the rhetoric of ethnic hatred to create social categories of inclusion and exclusion, under the disguise of protecting the interests of their groups. Each group came to believe that the other ethnic group(s) would deny them access to already limited resources, thus infringing upon their rights and ability to lead fulfilling and productive lives.

In Bosnia, the competition over resources manifested as an inter-ethnic struggle over future institutional arrangements/ethnic composition and status of the country. It was fueled by the efforts of political entrepreneurs to capitalize on opportunities of change and by the growing ethnic intolerance. Competition and intolerance eventually escalated into the preparation for and the beginning of a violent armed conflict.

Case Study Conclusion

In summary, the collapse of communism and the ensuing processes of democratization presented the structural change that caused a general sense of economic, political, and social insecurity, and uncertainty in Bosnia. The existence of the historical memories of ethnic grievances provided a conflict potential and grounds for revival of ethnic animosities. During the communist rule, the leaders in former Yugoslavia suppressed the expression of ethnic identities and “united” different ethnic groups under the umbrella of the communist party.

Once the communist structures collapsed, the mechanisms to mitigate ethnic emotions and conflict were no longer in place. The political entrepreneurs emerged as “nationalist leaders” and used the conflict potential of ethnicity by manipulating ethnic emotions and reviving the historical memories of grievances. The uncertainty of the new situation caused the ethnic groups to compete for resources fearing that their group would be disadvantaged and left behind unless they asserted themselves and attempted to secure their rights. The combination

95 Susan L. Woodward, “Intervention in Civil Wars – Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Working Paper, Institute of

War and Peace Studies, Columbia University, 1997, in Columbia International Affairs Online, http://www.ciaonet.org

, (accessed 26 January 2005). http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪21 of these factors created the conditions and processes which eventually culminated to the level of armed hostilities.

Thirteen years after the violence ended in Bosnia, the country remains divided along ethnic lines. In order to lessen the conflict potential of ethnicity and create a stable future for

Bosnia, international and local peacebuilding efforts should focus on establishing mechanisms that focus on promoting inter-ethnic reconciliation and tolerance.

Conclusion

In this article, I proposed a conceptual framework for understanding the causes of ethnic conflict. I argued that ethnic conflict is caused by a combination of factors: a major structural change, ethnic emotions stemming from historical memories of grievances, manipulation of ethnicity by political entrepreneurs, institutional factors that facilitate ethnic intolerance, and competition over resources and rights. I argued that all five factors must be present for ethnic conflict to occur. Primordialist theory points to the role of ethnic emotions based on historical memories of grievances, while the other three theories explain how the rest of the factors interact with ethnic emotions and each other to lead to ethnic conflict. This framework was applied to the case of ethnic conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In order to devise effective peacebuilding strategies, it is necessary to recognize and address the multiple factors that cause ethnic strife. Analysis of ethnic conflicts along multiple dimensions provides a basis for a more comprehensive approach to peacebuilding and post-conflict development in ethnically divided societies.

http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪22

References

Akbar, Ahmed S. 1995. Ethnic Cleansing”: A Metaphor of Our Time?

Ethnic and Racial

Studies 18(1):1-20. Bonacich, Edna.1972. A Theory of Ethnic Antagonism: The Split Labor

Market. American Sociological Review 38: 547-59.

----- and J. Modell, J. 1980. The Economic Basis of Ethnic Solidarity: Small Business in the

Japanese American Community. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Blagojevic, Bojana. 2004. Ethnic Conflict and Post-Conflict Development: Peacebuilding in

Ethnically Divided Societies . Ph.D. diss., Rutgers University. Bringa, Tone. 2002.

Averted Gaze: Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina from 1992-1995. In

Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide, edited by Alexander Laban

Hinton. Berkeley: University of California Press. Brunner, Georg. 1996. Nationality

Problems and Minority Conflicts in Eastern Europe .

Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation Publishers. Bugajski, Janusz. 1994.

Ethnic

Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies,

Organizations, and Parties . Center for Strategic and International Studies, Armonk:

M.E. Sharpe. Burg, Steven L. and Paul S. Shoup. 1999. The War in Bosnia-

Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. Clinton, Bill. 1994. State of the

Union Address 1994. Transcript of Clinton’s Address. New

York Times , January 26. Crawford, Beverly. 1998. The Causes of Cultural Conflict:

An Institutional Approach. In The

Myth of ‘Ethnic Conflict, edited by Beverly Crawford and Ronnie D. Lipschutz.

International and Area Studies Research Series/Number 98. Berkeley: University of

California.

----- 1998. The Causes of Cultural Conflict: Assessing the Evidence. In

The Myth of ‘Ethnic

Conflict, edited by Beverly Crawford and Ronnie D. Lipschutz. International and

Area Studies Research Series/Number 98. Berkeley: University of California. De

Varennes, Fernand. 2003. Peace Accords and Ethnic Conflicts: A Comparative Analysis of Content and Approaches. In Contemporary Peacemaking: Conflict, Violence and

Peace Process, edited by John Darby and Roger MacGinty. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan. Dick, C. J. 1992. Serbian Responses to Intervention in Bosnia

Hercegovina. British Army

Review , 102:18-25. Dixon, William J. 1994. Democracy and the Peaceful Settlement of International Conflict.

American Political Science Review 88(1):14. Drew, Elizabeth.

1992. Letter from Washington. New Yorker , July 2.

http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪23

Economist Intelligence Unit. 1995-96. Country Profile: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia,

Slovenia. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit. Enloe, Cynthia. 1981. The

Growth of the State and Ethnic Mobilization: The American

Experience. Ethnic and Racial Studies 4: 123-36. Fearon, James D. and David D.

Laitin. 1996. “Explaining Interethnic Cooperation.” The

American Political Science Review 90(4):715,730. Ganguly, Rajat. 1998. Why Do

Ethnic Groups Mobilize? In National Identities and Ethnic

Minorities in Eastern Europe, edited by R. Taras. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Glenny, Misha. 1992. The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. London: Penguin

Books. Gurr, Ted Robert. 1993. Why Minorities Rebel: A Global Analysis of Communal

Mobilization and Conflict Since 1945. International Political Science Review 14(2).

Hannan, Michael T. 1979. The Dynamics of Ethnic Boundaries in Modern States. In National

Development and the World System , edited by J. W. Meyer and Michael T. Hannan.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hechter, Michael. 1977. Internal Colonialism:

The Celtic Fringe in British National

Development, 1936-1966. Berkeley: University of California Press.

----- 1978. Group Formation and the Cultural Division of Labor. American Journal of

Sociology 84(2):293-318. Hodson, Randy et al. 1994. National Tolerance in the

Former Yugoslavia. The American

Journal of Sociology 99(6):1535. Horowitz, Donald L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in

Conflict. Los Angeles: University of California

Press. Jalali, Rita and Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1992-93. Racial and Ethnic Conflicts:

A Global

Perspective. Political Science Quarterly 107(4):595-597, 600. Karantnycky, Adrian et al. (eds). 1999. Nations in Transit 1998: Civil Society, Democracy, and Markets in East Central Europe and the Newly Independent States . New

Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, Freedom House. Kaufman, Chaim. 1996. Possible and Impossible Solutions to Ethnic Wars. International

Security 21(2):138, 143. Kaufman, Stuart J. 1996. Spiraling to Ethnic War: Elite,

Masses, and Moscow in Moldova’s

Civil War. International Security 21(2):109. Kposowa, A.J. And Jenkins, J.C.

1993.‘The Structural Sources of Military Coups in

Postcolonial Africa, 1957-1984. American Journal of Sociology 99(1):126-63. Lake,

David A. and Donald Rothchild. 1996. Ethnic Fears and Global Engagement: The

International Spread and Management of Ethnic Conflict. Working Paper. In

Columbia International Affairs Online, http://www.ciaonet.org.

----- 1996. Containing Fear: The Origins and Management of Ethnic Conflict. International

Security 21(2):41. Lewis, Bernard. 1992. Muslims, Christians and Jews: The Dream of Coexistence. New York

Review of Books , March 26.

http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Bojana Blagojevic ▪24

Lijphart, Arend. 1999. Terms of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-

Six Countries . New Haven: Yale University Press. Morris, S. 2001. Assessing Conflict

Vulnerability. Democracy Dialogue, Technical Notes from USAID Office of Democracy and Governance. Nagel, Joane. 1986. The Political

Construction of Ethnicity. In Competitive Ethnic Relations , edited by Susan Olzak and Joane Nagel. Boston: Academic Press. Nielsen, François.

1985. Toward a Theory of Ethnic Solidarity. American Sociological

Review 50(2). Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development - United

States Agency for

International Development (OECD-USAID). 2003. Land, Conflict and Development:

What Role of Donors? Summary. OECD-USAID Informal Experts’ Seminar, June 19 and 20. Olzak, Susan and Elizabeth West. 1991. Ethnic Conflict and the Rise and Fall of Ethnic

Newspapers. American Sociological Review 56:91, 458-74. Olzak, Susan and Joane

Nagel, eds. 1986. Competitive Ethnic Relations . Orlando and Boston:

Academic Press. Petersen, Roger Dale. 2002. Understanding Ethnic Violence: Fear,

Hatred, and Resentment in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prazauskas, Algis. 1991. Ethnic Conflicts in the Context of Democratizing Political Systems.

Theory and Society 20:581-2, 592-6.

----- 1995. Ethnic Identity, Historical Memory, and Nationalism in Post-Soviet States.

Working Paper. In Columbia International Affairs Online , http://www.ciaonet.org.

Reychler, Luc. 1999. Democratic Peace-Building and Conflict Prevention: The Devil is in

Transition. Leuven: Leuven University Press, Center for Peace Research and Strategic

Studies (CPRS), 1999. Roe, Paul. 2005. Ethnic Violence and the Societal Security

Dilemma. New York: Routledge. Rothschild, Joseph. 1981. Ethnopolitics: A Conceptual

Framework. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Snyder, Jack. 1993. Nationalism and the Crisis of the Post-Soviet State. Survival 35(1): 5-26

----- 2000. From Voting to Violence: Democratization and Nationalist Conflict. New York:

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Somer, Murat. 1997. Explaining the Hardly

Predictable: Causes and Consequences of

Ethnification. Working Paper. In Columbia International Affairs Online, http://www.ciaonet.org. Suny, Ronald Grigor. 2002. Why We Hate You: The Passions of Religious and Ethnic

Violence. A Talk for Purdue University, November 7.

----- 2001. “Constructing Primordialism: Old Histories for New Nations,” The Journal of

Modern History 73(4):869-870, 896. Szayna, Thomas S. 1994. Ethnic Conflict in

Central Europe and the Balkans: A Framework for U.S. Policy Options. Santa Monica: Rand.

http://globalaffairsjournal.org

Causes of Ethnic Conflict ▪25

Vejvoda, Ivan. 1996. By Way of Conclusion to Avoid the Extremes of Suffering. In

Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth, edited by

David Dyker and Ivan Vejvoda. London: Addison Wesley Longman. Williams, R.M.

1994. The Sociology of Ethnic Conflicts: Comparative International

Perspectives. Annual Review of Sociology 20:55. Woodward, Susan L. 1995. Balkan

Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution after the Cold War .

Washington DC: The Brookings Institution.

----- 1997. Intervention in Civil Wars – Bosnia and Herzegovina. Working Paper. Institute of

War and Peace Studies, Columbia University. In Columbia International Affairs

Online, http://www.ciaonet.org. Yinger, M.J. 1985. Ethnicity. Annual Review of

Sociology 11:165. Zimmermann, W. 1995. Memoirs of the Last American Ambassador to

Yugoslavia. Foreign

Affairs 74(2):20. Zupanov, Josip et al. 1996. A Breakdown of the Civil Order: The

Balkan Bloodbath. -

International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 9(3): 405-6, 413-4, 421.

http://globalaffairsjournal.org